Rethinking an American Mascot: Why New Research Says the Teddy Bear Needs a Facelift

The American icon has a long history of bloodsport and conservationism (Photo: BioScience)

For most of us, the first “wild animal” we meet doesn’t growl, forage, or maul salmon in a stream. It’s round, fuzzy, and named something like Mr. Snuggles. Before we ever hike a trail, we’ve already hugged a bear.

That bond isn’t trivial. Before understanding ecosystems or conservation, we often form an emotional connection with plush versions of animals. They shape our earliest ideas of what nature is. And those impressions tend to stick.

Despite their reputation, teddy bears were born out of bloodsport and politics. Their origin story starts in 1902, on where President Theodore Roosevelt famously refused to shoot a cornered black bear. A cartoonist turned the moment into satire, a candy‑shop owner turned the cartoon into a stuffed animal, and suddenly the rough‑riding president had accidentally invented the world’s most huggable mascot.

Fast‑forward a century, and scientists are now asking a question no one saw coming: Did 100 years of plush redesign turn the wild’s most feared predator into a comfort object—and change how we think about nature itself?

From Predator to Plush—the Design Drift

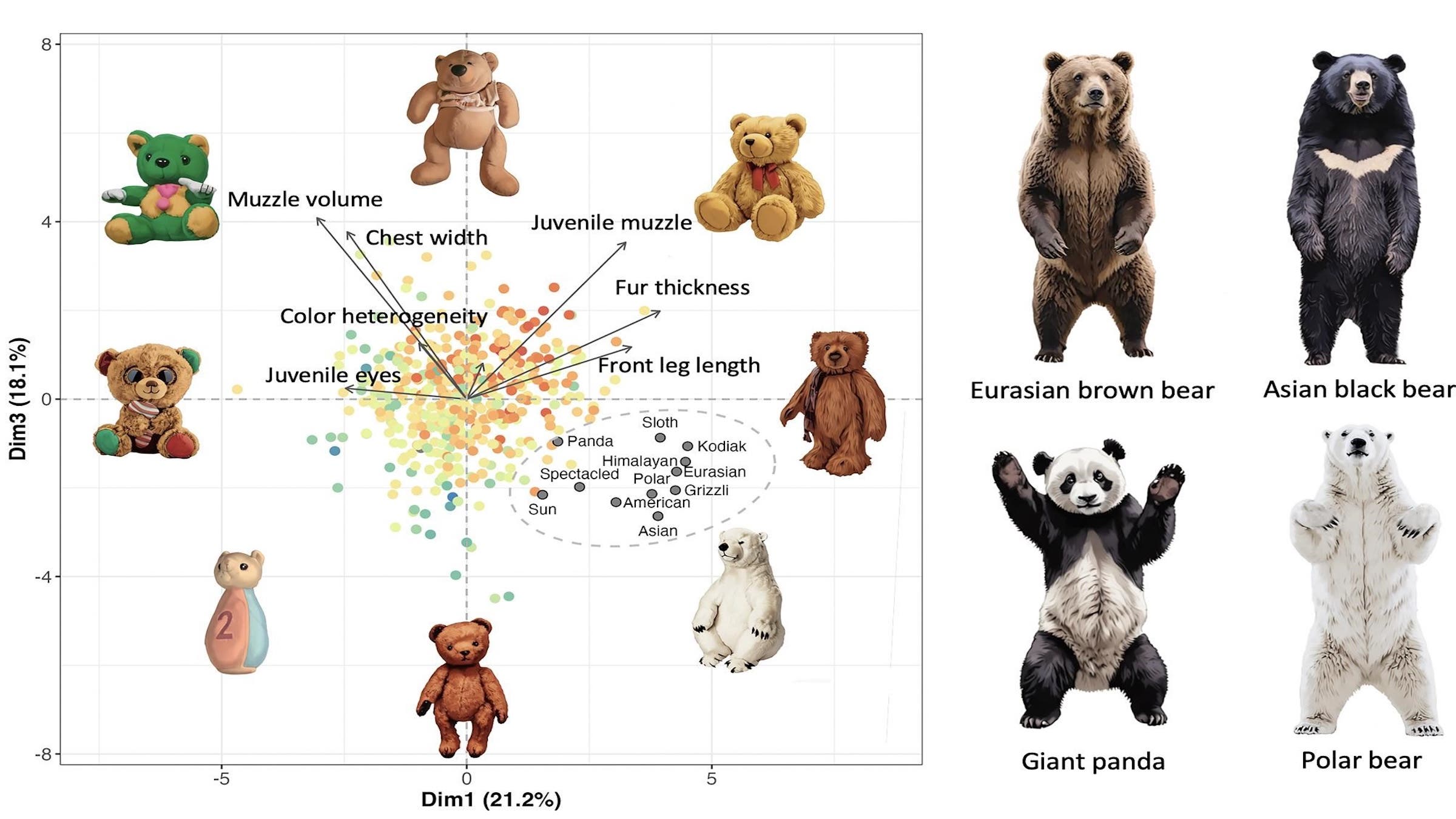

A century after Roosevelt’s hunting trip, the teddy bear has gone on a complete evolutionary detour. In 2025, researchers led by ecologist Nicolas Mouquet published a study in that did something hilariously scientific: they treated teddy bears like a species. Using morphometrics—actual measurements of body parts—they analyzed 436 plush bears and compared them to 11 real species.

The result? Teddy bears don’t just differ from real bears. They orbit a different aesthetic galaxy. As the researchers put it, “The cutest teddy bears are located in the upper right of the principal component analysis… characterized by large chests, juvenile muzzles… homogeneous coloration and long front legs.”

That “upper right quadrant” of the chart might as well be called the Teddy Bear Cutetron. If real bears lived there, they’d have three-inch legs, moon-pie faces, and pastel fur. Spoiler: none of them do. Even pandas—poster child of adorableness—don’t match the plush ideal.

Why do these design tweaks work so well? They tap into what ethologists call the , or “baby schema,” a bundle of traits like big eyes, oversized heads, and round faces that humans instinctively find cute because they remind us of babies. In nature, those cues help us care for infants. In plush design, they’re cranked up to guarantee we care for polyester ones. But cuteness alone doesn’t explain why so many of us still have a childhood bear tucked away in a closet—or why losing one can feel like a small emotional crisis. There’s more going on than button eyes and baby-face math. It turns out, teddy bears don’t just look sweet. We believe they feel something, too.

The Psychology of Attachment: Why Your Teddy Bear Felt So Real

In his 1953 paper, “,” psychologist Donald Winnicott referred to teddy bears as “transitional objects”—comfort items that help children navigate the uncertain space between themselves and the world. A bear, a blanket, a ragged bunny: they’re not just toys, they’re emotional life rafts.

And here’s where the connection deepens. Children don’t just cling to teddy bears; they animate them. In a by researchers at the University of Bath, children were significantly more likely to attribute thoughts and feelings to their own cherished toy than to other familiar toys. Mr. Snuggles isn’t just soft—he’s sentient.

There’s a recipe behind that illusion. Make something soft and face-having, and the human brain will happily anthropomorphize it. A published in the Journal of Cognition and Development added another layer: children often prefer their original, unique teddy over an identical replica. Ownership, combined with history, makes the bond feel irreplaceable.

That’s what makes the teddy bear so powerful—and so quietly risky. When your first animal is soft, silent, and always within reach, it’s easy to forget that real nature is louder, messier, and not always comforting. For more and more kids, that plush ambassador isn’t just the first creature they connect with—it may be the only one.

Nature, Replaced a.k.a. the “Extinction of Experience”

Childhood used to come with mud, bugs, and scraped knees. Now, for many, it’s more screen time than stream time. In their influential Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, ecologists Masashi Soga and Kevin Gaston coined the term “extinction of experience” to describe the progressive loss of direct human contact with nature.

When forests, streams, and critters fade from childhood, something else takes their place: symbolic wildlife. Emotional templates for nature are increasingly composed of stuffed animals, cartoons, and viral pet videos. As the authors warn, “As direct contact with biodiversity fades, symbolic representations gain power.”

But when our stand-ins for nature are this far removed from reality, the connection begins to blur. The average toy bear looks more like an animated sidekick than a grizzly. So what happens when your first bear is plush, purple, and named Cupcake? The emotional bridge may feel real—but it leads you to a synthetic wilderness. However, it may still work. Cuteness pulls us in, makes us care, and it’s been steering our instincts for a long time.

Cute Is Powerful—But Also Biased

Let’s be fair: cuteness works. It sparks empathy and creates protective instincts. That’s why panda mascots rake in donations and why campaigns to “save the seals” feature big-eyed pups instead of, say, mussels. Plush versions do the same job at home—hooking us emotionally before we know anything about ecosystems.

The reality is that our care isn’t evenly distributed. We care about what’s cute, not what’s ecologically vital. Conservation groups know it. Toy companies know it. Scientists are now starting to warn about the potential side effects. As one recent put it, “If the bear that comforts a child looks nothing like a real bear, the emotional bridge it builds may lead away from, rather than toward, true biodiversity.”

That disconnect matters because the teddy bear has become more than a bedtime buddy. As scholar Donna Varga describes in her essay “Teddy Bear Culture: Childhood Innocence and the Desire for Adult Redemption,” it is now a “global ambassador of comfort.” That’s a lot of weight for something stuffed with fluff.

The risk? We may be raising generations whose emotional connections are to animals that don’t exist outside the plush aisle. Great for sales. Not so great for biodiversity. The teddy bear isn’t going anywhere. However, if it’s going to continue representing nature, it may need a bit of a redesign.

So What Do We Do, Besides Cry into a Build-a-Bear?

Researchers behind the study suggest a simple solution: diversify the plush aisle. A little less pastel, a little more ecological truth. Bigger paws, shaggier fur, maybe even the occasional rough edge. If we want kids to care about the full spectrum of biodiversity, the toys that introduce them to “wildness” shouldn’t all look like they’re straight out of a Saturday-morning cartoon.

The conservation world offers a useful parallel. Campaigns mix emotion with facts: a panda poster paired with habitat stats, a dolphin calendar paired with data on overfishing. Why not do the same with toys? Pair the plush with field trips, storybooks, or classroom lessons that link the stuffed animal to the real one. Educators are already experimenting with storytelling that blends cuteness with biology—and it works.

This isn’t about rejecting comfort. It’s about recalibrating the connection. If we want kids to carry their love of nature beyond the toy box, maybe the first bear they hug should look a little more like the one they’ll never meet in the woods.