Before last year’s World Half Marathon Championships in Gdynia, Poland, a young British distance runner named Jake Smith had a call with scientists from a small company his agent had connected him with. They’d crunched the data from his performance two weeks earlier at the London Marathon, where he’d struggled in his assigned role as a pacer, and had a simple message for him: “They literally said, ‘You need to eat more,’” he recalls.

On the back of his upper right arm, the 22-year-old was wearing a circular adhesive patch about an inch across, with a tiny filament embedded into his flesh. It was a continuous glucose monitor, or CGM—a device designed to track real-time blood sugar (also known as glucose) levels in diabetics, repurposed for athletes by an Atlanta-based start-up called in collaboration with the medical device giant Abbott. The data Smith uploaded after London showed that his glucose levels had started at a middling level and then declined steadily during the race. “By about ten or 11 miles, I was like, ‘This shouldn’t feel like this,’” he says. So in Poland on the day before the race, he chowed down on pasta, rice, chicken, vegetables, and fruit, and he kept a wary eye on the Supersapiens app on his phone. Whenever his levels started to dip, he ate more.

The next morning, after a breakfast of two bagels with Nutella, , and peanut butter, he took on the world’s best distance runners. His time of 1:00:31 was a massive personal best, smashing his own British under-23 record and good for 18th place overall. And his glucose levels—well, no one knows, because they were so high that they maxed out the sensor throughout the race. “They said they would love to know,” Smith says, “but the app just wouldn’t go any higher.”

In late 2019, I got a LinkedIn message from a guy named Brian Davis who wanted to meet for coffee and tell me about a company he and his partners were launching. The pitch, he told me after I’d signed the requisite NDA, was “the world’s first human fuel gauge.” The body runs on glucose, he explained, and a CGM would give athletes real-time insight in how well fueled they were and when and what they should eat.

Davis was in Toronto, where I live, to meet with a York University researcher named Michael Riddell, who is among the world’s leading experts on how people with diabetes respond to exercise. Diabetes is fundamentally a problem with glucose control, thanks to the absence or ineffectiveness of insulin, the body’s main tool for shunting glucose out of the blood and into your muscle or fat cells. The development and refinement of CGMs over the past decade has had a huge impact on the ability of people with diabetes to keep their glucose levels within a safe range. In particular, they’ve been crucial for , a pro cycling team whose members all have Type 1 diabetes—not just for the health and safety of the riders, but also for their performance. That was the insight that led Phil Southerland, co-founder of the cycling team, to launch Supersapiens in 2019. After all, he figured, athletes with diabetes aren’t the only ones who worry about bonking.

The idea of sticking CGMs on healthy people isn’t totally unprecedented. In fact, when I wrote about blood sugar levels in endurance athletes back in 2017, the podcaster and physician Peter Attia praised his CGM as “one of the most informative inputs I’ve had in my life.” But Supersapiens faced a couple of significant obstacles to their goal of selling to athletes. One was regulatory: in most places around the world, you need a prescription to get a CGM. When I met with Davis in 2019, they were hoping to get approval for non-prescription sales by mid-2020. Supersapiens ended up launching in Europe last fall, but remains unavailable in the United States. Thanks in part to COVID-related delays at the Food and Drug Administration, it probably �ɴDz�’t be approved until next year.

The other obstacle—which is, if anything, even knottier—is that the link between blood sugar and performance is really complicated. We’re not like cars, which simply run on gas until the tank is empty. Instead, our muscles run on a complex mix of fuels—not just fat and carbohydrate, but various forms of fat and carbohydrate (of which glucose is just one) stored in various places (of which the bloodstream is also just one), in a blend that depends on the intensity and duration of the task and the relative level of the various fuel tanks. And if glucose levels are complicated in people with diabetes, buffeted by stress and fatigue and hydration and dozens of other factors, they’re even more complicated in non-diabetics thanks to the action of insulin. Just because you have low blood sugar, in other words, that ��DZ����’t mean you’re about to bonk. And conversely, just because you have high blood sugar, that ��DZ����’t mean you �ɴDz�’t bonk.

Still, Supersapiens’ pitch is that some information is better than none. Perhaps the heartiest endorsement of this pitch came in June, when the Union Cycliste Internationale, cycling’s worldwide governing body, banned the use of glucose monitors in competition—a ban that currently applies almost exclusively to Supersapiens, and implicitly assumes that knowing your glucose levels gives you a competitive edge. “The fans don’t want to see Formula One in bike racing,” UCI innovations manager Mick Rogers . “They want surprises. They want unpredictability.”

Meanwhile, Supersapiens has signed partnership deals with World Tour cycling teams including Canyon-SRAM and Ineos (who can still use the CGMs in training) and the triathlon team BMC-Vifit, and will be the title sponsor for this year’s Ironman World Championships in Hawaii, where they’re still allowed in competition. They’ve also enrolled more than 400 pro athlete ambassadors, including luminaries like Kenyan marathoner Eliud Kipchoge, all of whom are uploading their data to the company for analysis. “Glucose levels in non-diabetics? We’re all a little unfamiliar with that,” admits Riddell, who is now a scientific advisor to the company. Elite-level training and racing adds another twist that makes this data trove unlike anything previously analyzed, he says: “Sometimes it’s high; other times, it’s quite low. It’s not abnormal, but it’s extreme.”

To observers like , a widely respected sports scientist at the Canadian Sport Institute Pacific with particular expertise in sports nutrition and metabolism, the biggest challenge for Supersapiens will be extracting actionable advice from this firehose of data. To that end, the company has recently hired ten more full-time scientists, bringing its science team to 12 out of a total headcount of over 70. Those researchers are getting tantalizing glimpses of, say, the minute-by-minute ebb and flow of glucose in Kipchoge’s bloodstream during this spring’s Hamburg Marathon. But can that data tell Kipchoge anything about what he should do differently next time? “I’m sure the unit measures accurately,” Stellingwerff says. “But my main question is: Why?”

You’ve only got about a teaspoon of sugar in your bloodstream, and your body is carefully engineered to keep it that way. Eat a triple scoop of ice cream, and your pancreas will release insulin to stash the extra sugar into your muscle and fat cells. Get chased by a lion, and stress hormones will trigger a surge of glucose from the liver into your bloodstream to give your muscles the quick fuel they need to fight or flee. During exercise, your muscles burn through glucose 100 times faster than they do at rest, but the delicate balance between supply and demand mostly keeps levels in your bloodstream within a tight range between about 70 and 140 milligrams per deciliter. That’s why you can’t simply assume that low glucose levels mean you’re running out of fuel.

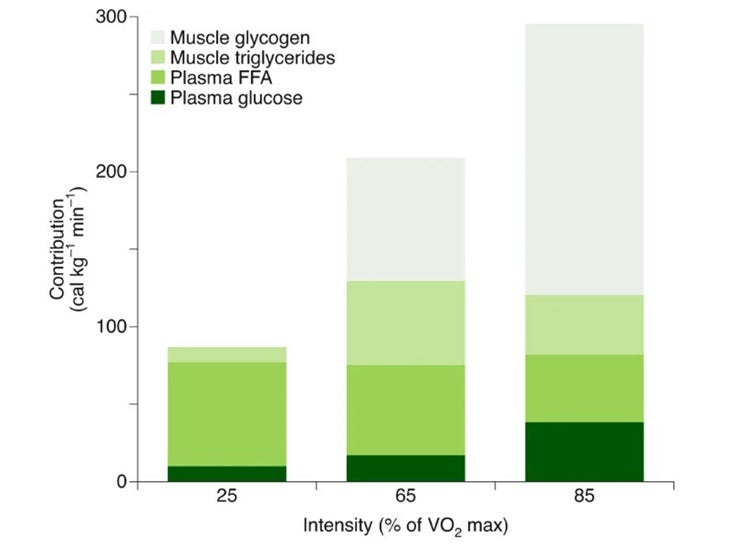

The key sources of energy for endurance are carbohydrates and fat, each of which can be stored in the muscles themselves or in the bloodstream. Here’s a graph, from , that shows the fuel mixture at different exercise intensities. Muscle glycogen and muscle triglycerides are carbohydrate and fat, respectively, stored in the muscle; plasma FFA (free fatty acids) and plasma glucose are fat and carbohydrate, respectively, circulating in the bloodstream.

At the lowest intensity, equivalent to an easy walk, fat provides nearly all of the fuel. At the highest intensity, equivalent to a brisk run, you’re burning mostly carbohydrate, but predominantly in the form of muscle glycogen rather than glucose. Looking at a graph like this, you might wonder why anyone would care about glucose levels.

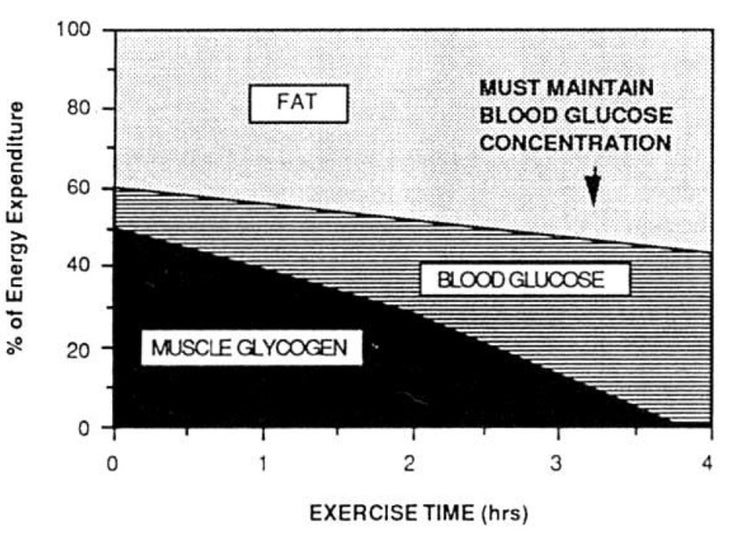

But if you stay on the bike or out on the trails for long enough, the picture gradually changes. You can only store enough glycogen in your muscles to fuel hard exercise for somewhere around 90 to 120 minutes. As those supplies dwindle, you begin to rely more on glucose. Here’s , based on studies by University of Texas researcher Edward Coyle and others during the 1970s and 1980s, showing how the fuel mix shifts during prolonged exercise:

After three or four hours, you’re burning 40 percent glucose—or at least, you are if you can keep your glucose levels high enough with sports drinks, gels, and other sources. If you just drink water, your glucose levels will drop, and performance will suffer. This is the observation, laid out by Coyle in , that underlies the entire sports drink industry.

Gatorade’s message is blunt: drink as much sports drink as you can so that, God forbid, your glucose levels will never drop. Supersapiens has a more nuanced message: drink or eat only as much as you need. After all, downing gels or drinks on the run costs time and often leads to an upset stomach or worse. We each have an optimal performance zone, neither too low nor too high, which we can discover by trial and error. “Below 110, I struggle to do longer rides,” says Southerland. “At 140 to 180 I feel best. But these levels are very personalized.” Smith’s zone looks more like a straight line, since he ran his breakthrough half-marathon almost entirely above 200 mg/dL, the upper threshold for the app. Kipchoge’s data remains confidential, but Todd Furneaux, the company’s president, is willing to speak in general terms: “All of our very elite athletes, when they’re running, even in an Ironman, they’re in the 180 to 200 range. They’re flatlining.”

The sensor that Abbott produces for Supersapiens is called the Libre Sense, and it’s billed as a “glucose sport biosensor.” In most respects, it seems to be identical to the FreeStyle Libre 2 CGM marketed to people with diabetes, but there are a few key tweaks. The sport version sends minute-by-minute updates to the app (or to a forthcoming wrist display) via Bluetooth, compared to a 15-minute interval in the regular model. And the measurement range is capped at 200 mg/dL, much lower than what you’d need to safely monitor your levels with diabetes—presumably an attempt to reassure regulators that it �ɴDz�’t be used as a medical device. The devices currently sell for 65 euros (roughly $77), and each unit lasts for 14 days once you apply it to your arm.

The fact that athletes like Smith are blowing the upper limit away is one indicator that the real-world data from athletes isn’t quite what the company expected. “Initially, we thought it was all about how to avoid a bonk,” Furneaux says. That idea may still have merit: in that collected CGM data during exercise from people without diabetes, Riddell notes that some people dropped well below 70 mg/dL, a range he says is associated with clear impairment of cognitive and physical function. Wearing a CGM might have warned these people that they needed more fuel, leading to better performance, though this claim hasn’t been tested.

It’s not clear whether the same observation applies to elite athletes, though. Louise Burke, an exercise nutrition researcher at Australian Catholic University who has worked closely with Australia’s Olympic teams for four decades, has seen athletes drop below 50 mg/dL with no apparent ill effects, while others show clear symptoms at around 75. “It may depend on the caliber of athlete,” she says. “Really elite athletes sometimes seem to be able to push lower. But basically we just don’t know.”

It’s not just about the bonk, though. Burke ran a study earlier this year with 14 elite Australian racewalkers to explore whether CGMs could pick up warning signs of chronic low energy availability, which is linked to health problems and overtraining. The myriad factors that make glucose levels bounce up and down during the day make it hard to draw meaningful conclusions, but Burke figures that the overnight levels when you’re sleeping might give a clearer signal of whether you’re getting enough calories to fuel your training. The results haven’t yet been analyzed, so for now Burke is interested but unconvinced. “I’m not saying it’s not going to be useful,” she says, “but I’m just saying it needs validation.”

Another possibility is using the CGM to fine-tune your carbohydrate loading before a major race, like Jake Smith, the British half-marathoner, did. Modern protocols generally involve a couple of days of very high carbohydrate intake to ensure that your muscles are fully stocked with glycogen at the start line. But the target of works out to about 16 cups of cooked pasta for a 150-pound athlete, which is no easy feat. You can’t use a CGM to directly measure your glycogen stores, but the Supersapiens app gives you a trailing 24-hour glucose average. That number could turn out to be a proxy for muscle glycogen stores, Furneaux says, because if it’s higher than normal, it means the excess glucose has nowhere else to go.

The last few hours before a workout or race can also be tricky. In as many as 30 percent of endurance athletes, a phenomenon called causes temporary feelings of light-headedness and weakness after a few minutes of exercise. The apparent culprit: eating simple carbohydrates 30 to 60 minutes before exercise, which triggers a rise in insulin levels that lingers for an hour or two. When you start exercising, you then have two different levers—insulin and exercise—trying to lower your glucose levels at the same time, causing them to drop too rapidly. “We see this a lot in the Supersapiens data,” Riddell says. “People are not fueling properly.” One countermeasure is to eat only in the last five to ten minutes before exercise, so your insulin levels don’t have time to rise. But wearing a CGM also gives you the option of figuring out exactly how your glucose levels respond to different types of food and different pre-workout timings.

Lots of novel and fascinating potential uses? Check. But what about actual evidence that sticking one of these things on your arm will make you faster? Abbott’s promises that it will “inform athletes about how to fuel appropriately, to fill their glycogen stores prior to a race and to know when to replenish during a race to maintain athletic performance.” Follow the relevant footnotes, and one leads to about the importance of refueling after exercise, while the other leads to in which four national-class swimmers wore a CGM for a week, with no intervention or performance measures.

Of course, the published literature sometimes lags behind elite practice. I emailed Armand Bettonviel, the Dutch sports nutritionist who was credited with , to get his take. Bettonviel is currently using Supersapiens with and three other athletes, but the first thing he emphasized was that interpreting data from the CGM is “not yet hard science.” He’s using it to build up a more data-driven picture of the various ways that Kipchoge’s body produces and uses glucose, and how they change under different conditions. Those general insights then allow him to drill down into the specifics of Kipchoge’s in-race drinking protocol, which was meticulously optimized during his sub-two-hour marathon attempts.

There are caveats, though. Bettonviel wants to determine Kipchoge’s “optimal blood glucose range,” and figure out the best pre-race and in-race fueling protocol to keep him there. But any good endurance athlete also needs to be able to burn fat efficiently: “I also strongly believe that metabolic flexibility could be a key performance indicator,” Bettonviel says. “All changes made based on blood glucose values could potentially affect this flexibility.” Moreover, he’s finding that what’s true for Kipchoge’s glucose responses isn’t necessarily true for the other athletes, making it difficult to formulate general rules. “Our team is still learning and analyzing,” he says. “We don’t jump to conclusions yet and any changes made are small ones.”

Of the exceedingly scant data in the published literature on athletes wearing CGMs, virtually all of it focuses on health rather than performance. Most notably, another Swedish study had 15 national-team endurance athletes wear a CGM for up to two weeks. Compared to non-athlete controls, they spent more time below the normal glucose threshold of about 70 mg/dL, mostly in the middle of the night; and they also spent more time above the upper threshold of about 140 mg/dL, mostly during the early afternoon. During their training sessions, on the other hand, they generally stayed within the normal range.

The idea of healthy, non-diabetic people using CGMs to further optimize their health is indeed . But it’s not without controversy. When Supersapiens announced its this spring, Tom Hughes, a medical doctor and sports science lecturer at Leeds Beckett University in Britain, . “I don’t think I have seen any evidence that blood glucose drops significantly during an Ironman,” he says—a claim that he’s tested on himself at least five times, taking old-school finger-prick readings of blood glucose when he felt he was bonking and observing levels well over 100 mg/dL. And he also isn’t convinced that obsessively tracking the peaks and valleys of your glucose readout during the day will tell you anything useful about your health. Instead, he says, it’s simply an opportunity to “stress about another number we don’t understand.”

To my surprise, even Riddell, the diabetes researcher and Supersapiens scientific advisor, admits some sympathy for this perspective. “The obsession with numbers is worth writing about,” he says. “Even among people with diabetes, the patient is often the one who ��DZ����’t want the CGM.” After all, you now have a stream of non-stop data that seems to be judging you, often negatively, after every meal and snack. And when you try to “fix” your behavior, your glucose levels don’t always respond in the way you expect. Riddell and his colleagues have identified at least 40, and perhaps as many as 200, different factors that influence glucose, making it tricky to sort out which signals really matter. If the device is going to catch on as an athletic aid, he says, Supersapiens “needs to be better at the ‘so what?’”

That’s easier said than done, but it’s why the company’s 12 scientists are poring through the data from their athlete ambassadors, looking for patterns and trends and telltale signals—and perhaps even new science. Already the data is yielding a changed understanding of what glucose looks like in serious athletes. The conventional view is that glucose values stay in the normal range even during hard training, as seen in the Swedish study. No one expected the sky-high values that Jake Smith and others produce during competition. “Medical textbooks say ‘glucose homeostasis is unperturbed by exercise in non-diabetics,’” says Riddell. “That’s wrong! We know that! So it’s 50 years out the window. We’re going to rewrite the textbook.”