It was a hard bonk during a 16-mile race up New Zealand’s 6,000-foot Avalanche Peak in 2013 that made Felicity Thomas, an undergraduate engineering student at the nearby University of Canterbury, begin thinking about her blood sugar levels. She’d tried to follow the usual sports nutrition advice, sucking down sugary gels to replenish the carbohydrates that her muscles were burning and to keep her blood sugar levels stable, but she struggled to get the balance right and ended up crawling to the finish before throwing up in an ice-cream bucket. Surely, thought Thomas, there must be a better way of managing in-race fuel.

As it happened, Thomas was an intern that summer at the university’s Center for Bioengineering, which was researching the clinical potential of continuous glucose monitors, or tiny sensors inserted under the skin of the abdomen that track blood sugar levels in real time. She took one of the expired monitors lying around the lab. If I could spot impending blood sugar lows before they happened, she wondered, would I be able to ward them off with a well-timed gel? Could I make myself bonk-proof?

A week of self-experimentation convinced Thomas that the technique might be useful, and she soon embarked on a PhD studying the potential uses of glucose monitoring in athletes. But the outcome of her initial pilot study on ten runners and cyclists, which was in the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, wasn’t what she expected. Instead of bonk-inducing blood sugar lows, the more common problem in her subjects, who typically averaged at least six hours of training a week, was high blood sugar throughout the day—an outcome that pointed to an elevated risk of Type 2 diabetes in these seemingly super-fit athletes. “I was incredibly surprised to see the results,” Thomas says. “It seemed contrary to almost everything else in the field.”

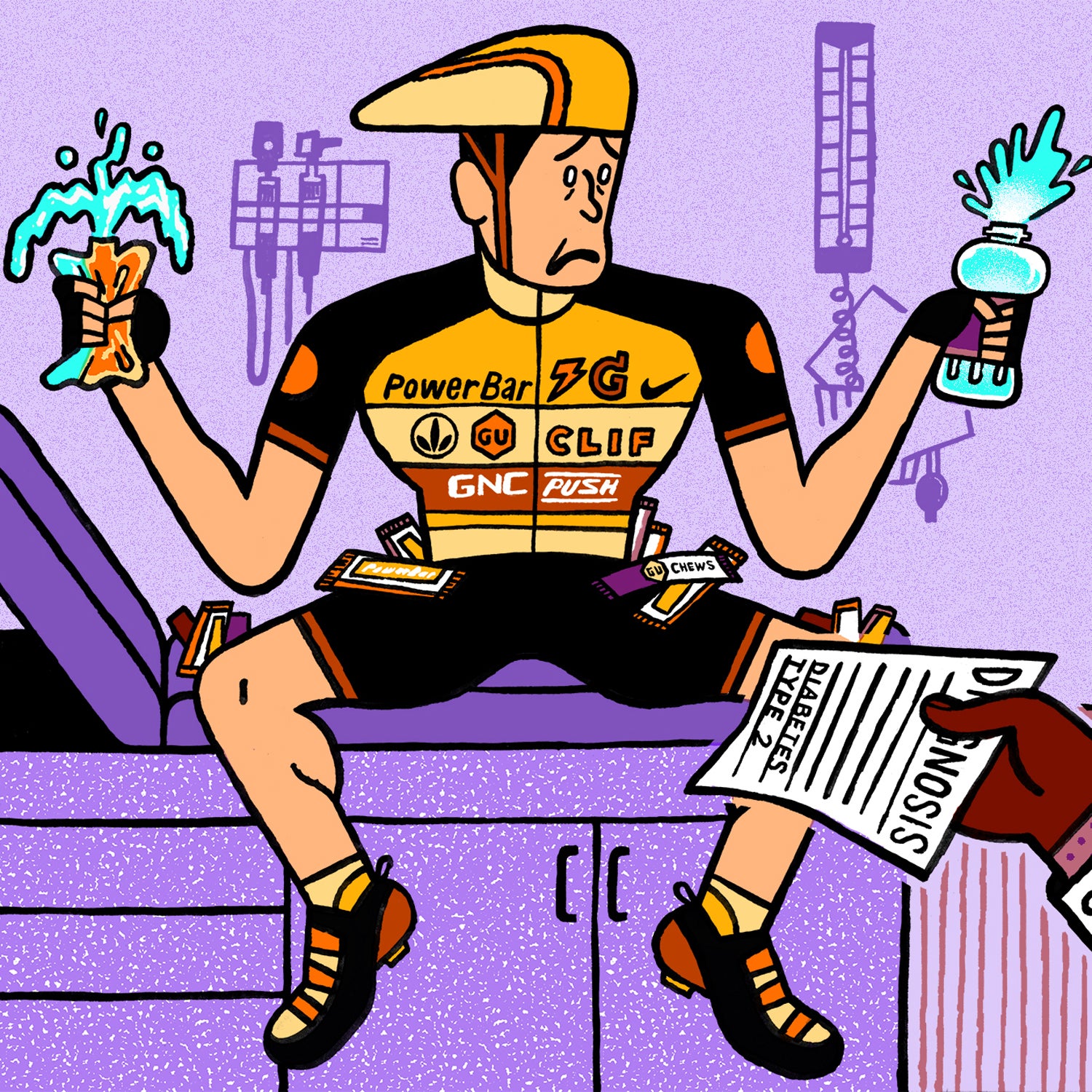

The idea that serious endurance athletes might be particularly susceptible to diabetes flies in the face of medical dogma. But it’s out there—on Reddit threads, in bestselling diet books, and now in the scientific literature.

More than a third of Americans have prediabetes, a condition marked by the body’s inability to keep blood sugar levels in a safe range, which often progresses to full-fledged diabetes. While Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition that usually develops at a young age, Type 2 diabetes is about ten times more common and can develop at any point in a person’s life. Both types of diabetes ravage organs, blood vessels, and nerves and, if left unchecked, can lead to blindness and limb amputation. Annual costs for the 29 million people in the United States with diabetes are now $245 billion and growing, .

In fact, the number of since 1980. This dramatic rise in Type 2 diabetes is usually attributed to obesity and lack of exercise, so the idea that serious endurance athletes might be particularly susceptible flies in the face of medical dogma. But it’s out there—on , in bestselling , and now in scientific literature. The thinking is that “the average endurance athlete consumes way too much sports drink,” explains Patrick Davitt, an assistant professor of exercise science at Mercy College, in Dobbs Ferry, New York. Large doses of sugar, independent of its calories, lead to blood sugar spikes that, it’s assumed, eventually dull your insulin sensitivity and raise your risk of Type 2 diabetes.

One of the first to make this connection in a sports context was a former surgeon named Peter Attia, who gave an in 2013 that has since been viewed more than 2 million times. A long-distance swimmer and cyclist, Attia recounted his surprise when, in 2009, he discovered that he had insulin resistance despite exercising for three or four hours a day. Attia, who went on to found the nonprofit research organization with prominent low-carb advocate Gary Taubes, suggested that the underlying cause of his problems might be an excess of carbohydrate—in particular, refined grains, sugars, and starches. In a similar vein, , the South African researcher whose book remains perhaps the best-known guide to the science of running, announced in 2009 that he too had developed prediabetes and blamed it on the carb-loading diet that he promoted for years.

For endurance athletes, the suggestion that their seemingly healthy obsession might carry a hidden health cost is hardly new. Such claims—that , say, or —don’t always stand up to scrutiny. And the scientific consensus on this point still leans strongly in the opposite direction. have identified obesity, inactivity, and genetics as the three key risk factors for developing Type 2 diabetes, says Edward Horton, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a senior investigator at the Joslin Diabetes Center, in Boston, who has spent a half-century working with both non-diabetic and diabetic endurance athletes while studying glucose metabolism. Serious endurance athletes are neither obese nor inactive, and they can’t change their genes.

The demands of training mean that your muscles burn through so much glucose that high blood sugar should be a near-impossibility, says Horton, a long-distance skier and runner himself. “I’m a strong believer in a well-balanced diet,” he says. “But if you’re a high-level endurance athlete, you can eat what you want.” In fact, according to , Tour de France riders consume a pound of sugar per day, and found that they get 20 percent of their calories from the sugar they heap into their tea and porridge.

Researchers have found that elite endurance athletes have insulin sensitivity that is roughly three times higher than healthy nonathletes, meaning they can rapidly get the sugar they consume out of their bloodstream and into their muscles without having to produce excessive amounts of insulin. According to from the University of Copenhagen, the two factors seem to balance out perfectly: Athletes boost their insulin sensitivity in exact proportion to their increased carbohydrate intake, so they end up producing about the same overall amount of insulin, on average, as healthy nonathletes. “At worst, it’s a wash,” says Michael Joyner, a physiologist at the Mayo Clinic, in Minnesota.

Tour de France riders consume a pound of sugar per day, and a study of Kenyan runners found that they get 20 percent of their calories from the sugar they heap into their tea and porridge.

What little epidemiological evidence exists for elite athletes seems to bear this out as well. In 2014, a team led by Merja Laine, a medical researcher at the University of Helsinki, on nearly 400 former elite athletes who represented Finland in major international competitions between 1920 and 1965. The athletes were divided into three categories: endurance sports, such as running and cross-country skiing; power sports, like boxing and weight lifting; and mixed sports, including hockey and basketball. Overall, compared with nonathlete controls, the former athletes were 42 percent less likely to have impaired glucose tolerance and 31 percent less likely to have diabetes. More specifically, the former endurance athletes had the lowest risk, with a whopping 47 percent reduction in diabetes prevalence, compared to 34 percent in power sports and 25 percent in mixed sports. And published earlier this year looked at how much money each group spent annually on diabetes medication. Researchers found that the controls spent an average of 376 euros per year, the former power athletes averaged 393 euros, the former mixed-sport athletes averaged 272 euros, and the former endurance athletes averaged just 81 euros per year.

Such findings leave questions open, of course. For one thing, Laine points out, “the training system of that time differs from nowadays.” Gatorade was only invented in 1965, the last year the athletes in the study competed internationally; today’s athletes may face a different set of risks. ( didn’t show up until the late 1980s—co-developed, as it happens, by Tim Noakes.) It’s also possible the low rate of Type 2 diabetes in endurance athletes is simply correlation, not causation—a result of the genetic characteristics of good endurance athletes rather than a protective effect of training. “Maybe the successful elite and Olympic endurance athletes are the ones who survive the gauntlet of sports nutrition and still perform well, so we’ve selected for their ability to not get sick while on those diets,” suggests , a bestselling fitness author and Ironman triathlete.

Overall, though, the metabolic characteristics of endurance athletes don’t suggest a group at elevated risk of diabetes, says Javier Gonzalez, an assistant professor of human physiology at the University of Bath in England who studies exercise metabolism. “I’m open to the idea,” he says, “although I currently see very little, if any, good evidence to support it.”

So, where does this idea that endurance athletes are a diabetes epidemic waiting to happen come from?

The link between carbohydrate intake in endurance athletes and elevated blood sugar is most widely accepted among low-carbohydrate, high-fat (LCHF) converts, who often take it as both an article of faith and a source of motivation. “Athletes with prediabetes are surprisingly common,” on one of the Reddit threads devoted to the topic, who noted that he had been on a high-fat ketogenic diet for more than four years. I contacted him to ask whether he’d had high blood sugar prior to switching his diet or if he knew anyone who’d had that experience. “This has not happened to me,” he replied. “My observation was from a few podcasts and articles I came across.”

Still, there are truly elite endurance athletes who have developed Type 2 diabetes, notes Paul Laursen, an adjunct professor of performance physiology at Auckland University of Technology. Laursen points to Steve Redgrave, the five-time Olympic champion rower from Britain who was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes before the Sydney Games in 2000. Redgrave isn’t sure what, if anything, triggered it: “I haven’t asked too many questions about my condition,” he says. His involved a massive 6,000 calories a day, including plenty of pasta and sugary treats. But, Redgrave adds, he also has a family history of the disease through his grandfather.

Last year, Laursen co-wrote an article in the journal Sports Medicine Open titled “,” in which he argued that the superficial aerobic fitness of endurance athletes can hide metabolic problems like systemic inflammation and insulin resistance. That doesn’t, however, mean he thinks all endurance athletes are at risk. “The correct answer is: It depends,” says Laursen. The relevant risk factors include genetic differences, training patterns, and dietary habits. In other words, an athlete’s risk of developing prediabetes is entirely individual.

Laursen’s point is one that almost everyone acknowledges—including Peter Attia, whose professional focus these days is on tailoring individual approaches to maximizing longevity in his patients. “If you don’t take care of real people,” Attia says, “you don’t appreciate the heterogeneity in the population.”

For that reason, general statements about whether endurance athletes are at risk of diabetes are doomed to inaccuracy. At one extreme, “I think the probability that a Tour de France cyclist is going to get diabetes is as close to zero as possible,” Attia says. “There are absolutely athletes who can completely overwhelm the glucose disposal side such that it doesn’t matter at all what they eat. And furthermore, there are people genetically who can do that, whether they’re athletes or not.”

To that point, Israeli researchers recently used continuous glucose monitors to compare sample blood sugar data from two subjects. In one subject, eating a banana caused an immediate spike, while eating a cookie had no effect; in the other subject, . Though has for methodological flaws, it raises an important point: How can you eat right if “right” is different for everyone?

It’s possible the low rate of Type 2 diabetes in endurance athletes is simply correlation, not causation—a result of the genetic characteristics of good endurance athletes rather than a protective effect of training.

For both Attia and Laursen, the answer is to wear continuous glucose monitors (CGM), which are enjoying a among tech-savvy self-trackers despite being invasive and hard to obtain without a doctor’s assistance. “It’s one of the most informative inputs I’ve had in my life,” says Attia. Using a CGM has helped him understand how his blood sugar responds to foods, exercise, sleep, and stress.

Thomas, the New Zealand–based bioengineering researcher, has come to a similar conclusion. Her study of endurance athletes wearing CGMs showed that high blood sugar is indeed possible in runners and cyclists, with three of the ten subjects producing fasting levels in the prediabetic range. But the links between diet, training level, and blood sugar were far from clear: The athletes with the highest blood sugar weren’t necessarily eating the most carbs or exercising the least.

While Thomas sees a future of personalized nutrition, with CGMs becoming as ubiquitous as heart rate monitors, the data suggests some more immediate takeaways that don’t require any subcutaneous sensors: No matter what type of athlete you are, your food intake should match your training output, and you don’t need a sports drink and a gel to fuel during a one-hour jog or to recover afterward. “For years,” says Davitt, the Mercy College researcher, “the sports drink industry has been brainwashing us into thinking that we need to drink as much as possible and that glucose sports drinks are almost always superior for performance and recovery.”

Modern guidelines have evolved as well. The current American College of Sports Medicine on nutrition and athletic performance suggests that carbohydrate intake should be greater on hard training days and less on easy days—a practice that two-thirds of elite distance runners in reported following.

If you can get this balance right, then the overwhelming consensus of epidemiological and metabolic evidence suggests that rumors of a prediabetes epidemic among endurance athletes have been greatly exaggerated. Hitting the roads and trails will, if anything, dramatically reduce your risks of becoming insulin resistant—but it won’t make you immune.

If you’re eating like a Tour de France rider, just make sure you’re training like one, too.