Back in January—when the less prescient among us were still expecting that the year’s most oppressive news cycle would occur��during the U.S. presidential election—the International Olympic Committee that it would continue to forbid Olympic athletes from participating in any form of protest��or “political, religious or racial propaganda.”��

The IOC’s argument has always been that the Olympics are meant to be a respite from global conflict, and hence athletes must refrain from doing something as openly bellicose as taking a knee on the podium. It’s a position that was never particularly convincing, but given the events of recent months, the idea that sports can exist in an apolitical vacuum feels more untenable than ever. After the police killing of George Floyd incited what has been called the , American athletic leagues have shed .��NBA players are competing with ��printed on their jerseys. Even USA Track and Field, hardly a stalwart of progressive action, began selling earlier this month.

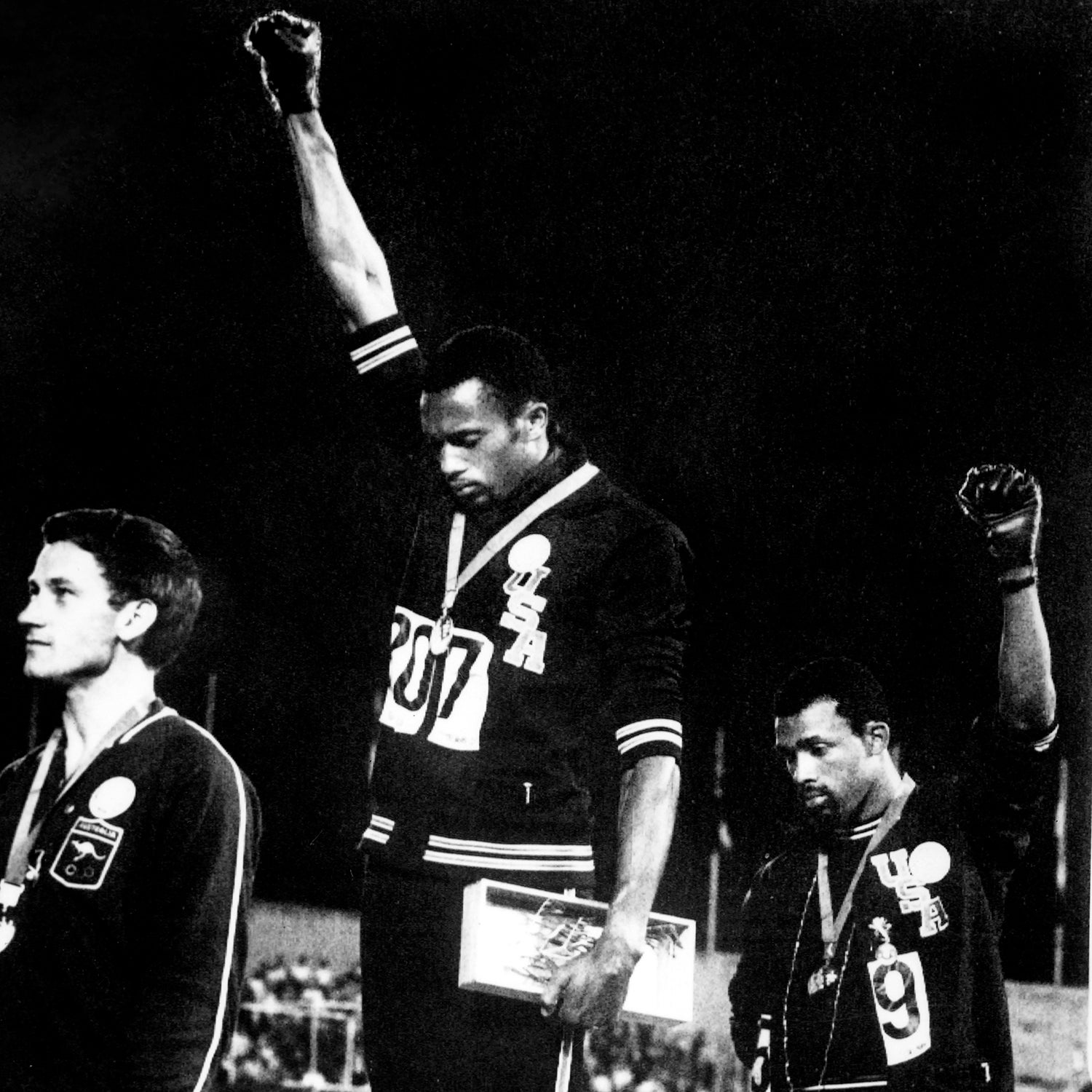

The USATF shirts feature an image of what is arguably the most recognizable act of rebellion at the Olympics: American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising their fists during the men’s 200-meter medal ceremony at the 1968 Games in Mexico City. More than 50 years later, the act, which was intended to call attention to the scourge of racial injustice, retains its symbolic potency. So much so��that last year the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee , not as mere athletes��but as “legends.” As I wrote at the time, there was some irony in this belated act of deification, since the USOC’s response in ’68 was to��suspend the two sprinters and force them to leave the Olympic Village—at the behest of the IOC.��

Now��a new documentary called attempts to further contextualize the moment. The 69-minute film, which is currently available to stream on and ,��was initially supposed to come out in 2018 for the 50-year anniversary of the Mexico City Games, but the delayed release has, if anything, made the project more timely. Indeed, it’s impossible to watch The Stand in 2020 without seeing current calls for racial equality echoed in the struggles of the past—a connection bolstered by the fact that the film presents former 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick��as the logical heir to Smith and Carlos’s legacy. While the comparison makes sense, it also threatens to obscure how different the stakes were for amateur��Black American athletes in the sixties, long before co-opting acts of protest was a viable marketing strategy for big business. (Kaepernick may have been ostracized by those ghoulish NFL owners, but he’s��also and was GQ’s ��in 2017.)

In setting up the context for the ’68 Olympic protest, The Stand begins by establishing the obvious: even though the Civil Rights Act was signed into law in 1964, segregation persisted. In an interview, Carlos remembers when, in 1967, despite being a nationally recognized sprinter for East Texas State, he was denied service at a bar in Austin because he was Black. In the film’s most affecting moment, Mel Pender, a war veteran who also competed in the sprints at the Mexico City Games, recalls when he took his ailing mother to the doctor and was forced to use a separate waiting room. He had just returned from Vietnam, and the indignity was more than he could bear. “I lost it,” Pender says. Half a century later, he can’t tell the story without tearing up.��

If these were the private humiliations that led to the medal-stand protest, the public impetus came from the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR). The movement initially called for Black athletes to boycott the ’68 Games and was led by a charismatic academic and activist named Harry Edwards, who��Smith and Carlos refer to as their “inspirational mentor.”

In the end, of course, Smith and Carlos didn’t boycott the Games, despite the fact that several of the OPHR’s demands—which included the ousting of Avery Brundage as IOC president—were not met. The Stand suggests that what compelled the athletes to their famous act of defiance was a sense that a debt had yet to be paid. As Smith says in the documentary: “I didn’t know what I was going to do, but I had to do something.”

Despite being a longtime track fan, I was unaware that Smith, who took gold in Mexico City, pulled a muscle in his groin during the semifinal of the 200 meters. He still won the heat, but the final was scheduled for later that same day. As he limped off the track, it seemed doubtful that he would even be able to take part. And yet��he rallied, managing to win the event in a world-record time of 19.83 seconds—without even properly warming up. In the documentary, Smith recalls the 200 final in exacting detail: the way his mind went blank in the first seconds after the gun went off��before becoming hyper focused on his running mechanics. In the home stretch, where Smith pulled away, consciousness dissolves into pure athletic grace: “not a thought, but muscle memory.” For those of us who care about this stuff, it’s��as thrilling as it is rare to hear a world-class athlete articulate what goes on inside his head (or doesn’t) in the heat of the moment.

I hate to say it, but Smith’s race recap inadvertently ends up being the heart of The Stand. Once the documentary turns its focus to the medal-stand protest, it faces the impossible task of trying to add to the gravity of a moment that is already among the most vaunted in the history of sports. Good luck with that. The majority of the documentary’s footage of Carlos comes from with the Civil Rights Project. In it��he is wearing a shirt with a giant clenched-fist logo—seemingly from his own . Thankfully, The Stand also includes some more raw interview footage of Smith and Carlos when they were angry young men. Before they were celebrated as civil rights heroes. Before they were brands.

But��in light of all the IOC’s eternal hand-wringing about any hint of athlete protest, it’s another scene��that makes the movie. Smith and Carlos were vilified in the American press for what happened in Mexico City, and after returning home to California’s Central Valley��in ’68, Smith remembers the first exchange he had with his hog-farming father.��

“I heard you did something that people didn’t like….��What did you do?” Smith recalls his dungaree-clad father saying. “I thought, Oh, I’m in trouble now.��And then I told him that I stood on the victory stand, raised my fist to the sky, and prayed a prayer for this country.” To which the elder Smith replied, “Well, that ain’t bad,” before going back to feeding his hogs.��