Last week, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) ô addressing its stance on Rule 50ãi.e. the section of the Olympic Charter which stipulates that, among other things, ãno kind of demonstration or political, religious, or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues, or other areas.ã Stating that the purpose of the rule was to protect the ãneutrality of sport,ã the IOC published a three-page document to help clarify how Rule 50 would be implemented and enforced at the 2020 Games in Tokyo.

In brief, Olympic athletes are prohibited from engaging in any acts of protest on the field of play, in the Olympic Village, or at any of the Olympic ceremonies. Athletes are allowed to ãexpress their viewsã on social media, at press conferences, and in the mixed zone. The IOC notes that ãexpressing views is different from protests and demonstrations.ã Examples of the latter include: ãany political messagingã and ãgestures of a political nature.ã

How does the IOC justify its vehement policing of all things political? The official answer is that in a divided world, the Olympics are supposed to represent a kind of safe space (both literal and symbolic) from global conflict. Per the IOC, any athlete who uses the Olympic platform to broadcast a personal agenda is compromising the sanctity of the occasion and effectively ruining it for everyone else. In its press release, the world governing body engaged in a little preemptive activist shaming: ãWhen an individual makes their grievances, however legitimate, more important than the feelings of their competitors and the competition itself, the unity and harmony as well as the celebration of sport and human accomplishment are diminished.ã

Shockingly, not everyone has been willing to give the IOC the benefit of the doubt on this. Over the past week, the organization has been repeatedly taken to task for claiming that the Games are apolitical.

ãOf course sport and politics are intertwined,ã the Guardianãs Sean Ingle , echoing a point George Orwell . ãThe Olympics, after all, is partly a giant willy-waving contest between nations,ã Ingle added. Needless to say, the ãwilly-wavingã is rarely confined to the field of play; itãs become routine for every Olympics to ô about what a nationãs medal tally says about things like GDP and other metrics of national prosperity.

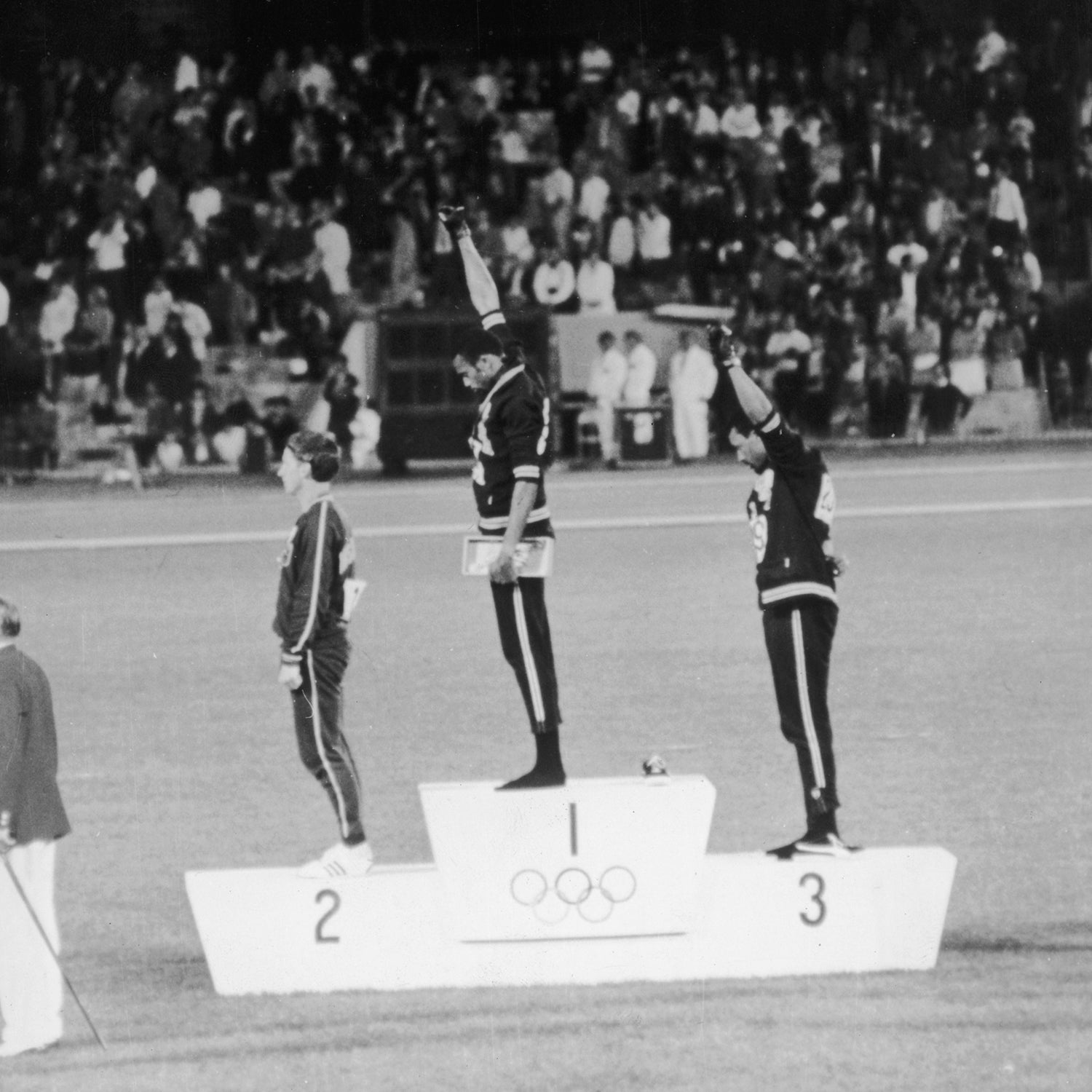

Earlier this week, Olympic bronze medalist John Carlos ô and made the point that forbidding political gestures was itself a political act.ô Carlos, of course, was involved in what has arguably become the most recognizable act of protestô in the history of the Games when he raised his fist with Tommie Smith on the medal podium in Mexico City in 1968.ô ã[The IOC is] way out of line with this,ã Carlos said. ãThe silencing of people is political.ã

The example of Carlos and Smithãs famous protest speaks to a hypocritical aspect of the IOCãs stance. As I wrote last year, the organization and its affiliated national committees are more than happy to co-opt the political elements of the Games if they can be used to burnish the Olympic brand. See: the US Olympic Committeeãs induction of Carlos and Smith into its official Hall of Fame last November for ãcourageously standing up for racial injustice,ã or ô citing the 2018 Winter Games as the principal reason that tensions have cooled between North and South Korea.

Finally, and not to harp on about what should be blatantly obvious to anyone paying attention, casting the Olympics as a politically neutral event is to willfully ignore how much it costs to put on one of these two-week shindigs. The Games are the epitome of what anti-Olympics activist Jules Boykoff cynically refers to as ãcelebration capitalism,ã i.e. a phenomenon where host cities take on enormous levels of debt from which private contractors (rather than the general public) often reap the benefits. Thereãs a reason, after all, that many cities are saying ãno thanksãô to the prospect of hosting the Olympics, and it isnãt that everyone hates race-walking. (As Bostonãs Mayor Marty Walsh put it when his city withdrew its bid for the 2024 Games, ãI refuse to mortgage the future of the city away.ã)

I wonder if thereãs not a more fundamental flaw in the way the IOC is cleaving to Rule 50. At least from where I sit, it seems like the governing body is trying to address a problem that doesnãt really exist. ãIt is a fundamental principle that sport is neutral and must be separate from political, religious or any other type of interference,ã the IOC notes in its athlete guidelines.

What constitutes ãinterferenceã here? Given the types of political protest weãve seen from athletes in Olympiads past, itãs difficult to see how these ãdiminish the accomplishmentsã of others or degrade the competition. Indeed, one of the remarkable things about the John Carlos/Tommie Smith protest in ã68 was that the other guy on the podiumãi.e. Peter Norman, the silver medal winner from Australiaãvoluntarily took part in the protest by donning an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge in solidarity.

To cite a more recent example, at the 2016 menãs marathon in Rio, Ethiopiaãs ô just as he was securing a second-place finish. The gesture was meant as a sign of solidarity with the Oromo, his countryãs largest ethnic group, who were being subjected to from the (Tigray-dominated) Ethiopian government at the time. Itãs hard to think of a more overtly political act and flouting of Rule 50, and yet the first and third place finishers in the raceãnamely Kenyaãs Eliud Kipchoge and the American Galen Ruppãdidnãt seem to notice. (While weãre at it, when Rupp, who is Catholic, finished the race seconds after Lilesa, he , but itãs doubtful that anyone interpreted this as religious propaganda.)

Will we see similar acts of protest this summer in Tokyo? The joke will be if the IOCãs stern warning ends up inadvertently inspiring more athletes to take a stand. Or a knee.