You may have noticed that these are ideologically divisive times. The current moment is so charged that the Super Bowl, our annual excuse to watch four hours of commercials while courting diabetes, was . Even its zillion-dollar-per-second ads were scrutinized for hints of partisanship. For some, the team you were rooting for became a de facto barometer of personal politics—as if somehow reveals your stance on immigration policy.

Against this backdrop, it’s tempting to believe there was once a time when sports were a refreshing respite from politics—a purer source of escapism, insulated from the raging debates of the day. But this view is a fantasy. Even in professional running (in some ways the antithesis of football), actions of dissent and political protest have repeatedly shown that sports never take place inside a cultural vacuum. The following are just a few prominent examples in running’s recent history when much more than athletic competition was at stake.

1966: Roberta “Bobbi” Gibb, Boston

After watching the 1964 Boston Marathon with the frenzied crowds at Wellesley College, Roberta Gibb, a natural athlete who’d grown up in nearby Winchester, knew she wanted to run the historic race herself. Unfortunately, she’d be forced to do it the hard way. “Women aren’t allowed, and furthermore are not physiologically able,” was the curt response from the race director when Gibb submitted an application to race in 1966. Undeterred, she rode a Greyhound bus from her San Diego home to Boston that April. On the morning of the race, Gibb, wearing a hoodie to conceal her ponytail, hid in the bushes near the starting line and jumped in with a pack of runners. She finished in three hours, 21 minutes, and 40 seconds, safely within the top third of finishers. Don’t underestimate the significance of Gibb’s banditing—this was a radically different America. “People don’t realize what it was like back then. It was hard for a woman to become a doctor or lawyer, run a business, live on her own. A woman couldn’t get a mortgage or even have a credit card in her own name. It was really claustrophobic,” Gibb . “And now, on top of it, we aren’t even allowed to run?” It wasn’t until 1972 that female entrants were officially recognized by the Boston Athletic Association.

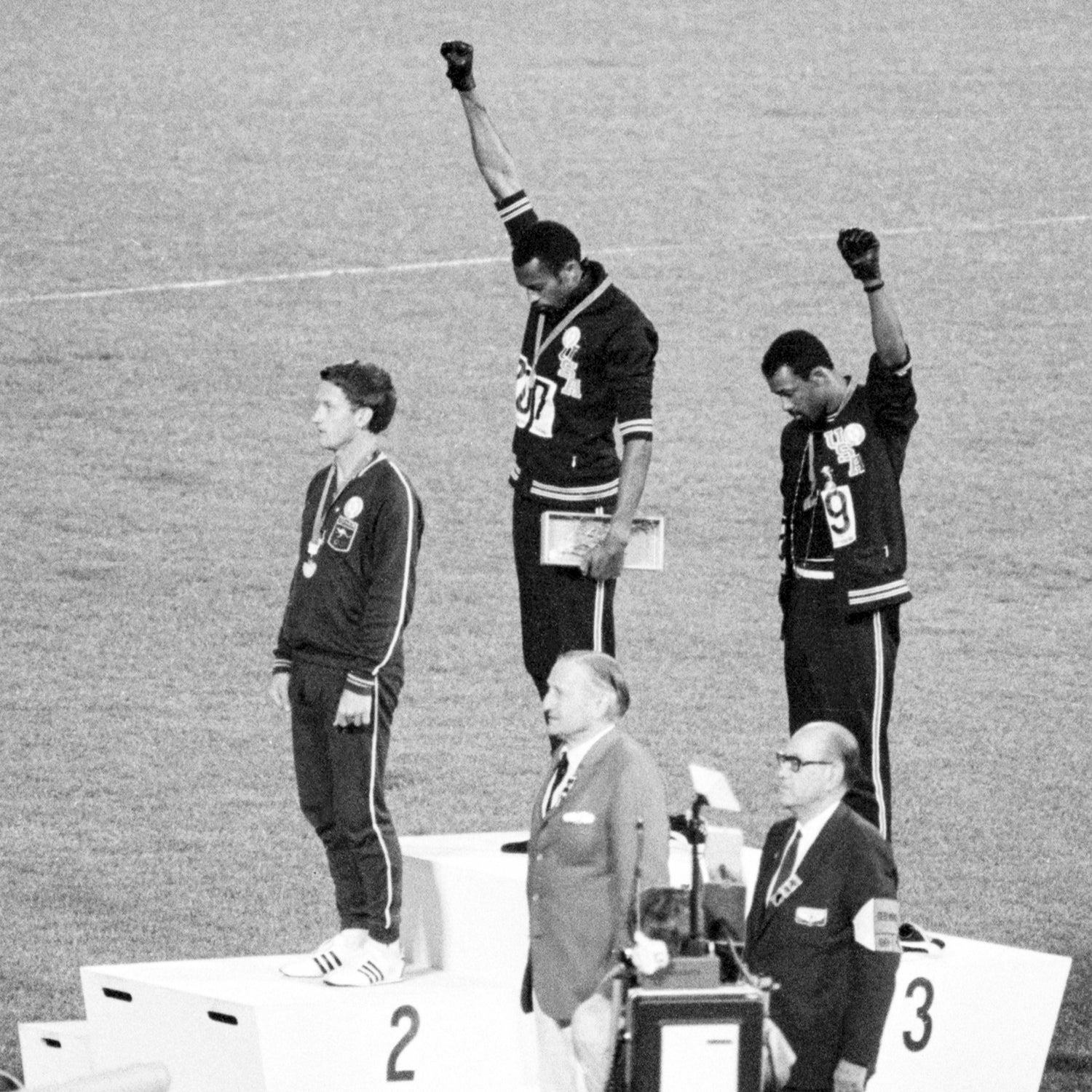

1968: Tommie Smith and John Carlos, Mexico City

Decades before Colin Kaepernick started , Tommie Smith and John Carlos staged what has since become perhaps the most iconic protest act associated with our national anthem. The 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City came during a year that had already seen mass protests in the United States, as well as the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. On October 16, Smith and Carlos won gold and bronze, respectively, in the men’s 200-meter sprint. When the two men stood on the podium after receiving their medals (shoeless to symbolize African American poverty), they bowed their heads during “The Star-Spangled Banner” and raised a black-gloved fist as a protest against racial injustice back home. The U.S. Olympic Committee suspended the two athletes for violating “the basic standards of good manners and sportsmanship,” according to about the incident. The two athletes and their families were subjected to years of vitriol after the games but never apologized for their act. “It’s one thing to receive accolades from your peers and family; it’s another to be proud of yourself,” Carlos last year. “For anything I’ve ever done in my life—and I’ve done quite a bit—I’ve never been more proud than of what I did in that demonstration.”

2000: Catherine “Cathy” Freeman, Sydney

“No kind of demonstration or political, religious, or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues, or other areas,” reads Rule 50 of , the notoriously strict rulebook for five-ring athletes. Like Tommie Smith and John Carlos before her, Aboriginal Australian sprinter Cathy Freeman would famously violate what the Olympic Committee considered appropriate behavior. At the 1994 Commonwealth Games, Freeman celebrated her victories in the 200- and 400-meter sprints by carrying both Australian and Aboriginal flags during her victory laps to celebrate her indigenous heritage. Commonwealth Games bigwig Arthur Tunstall rebuked Freeman for the act, pointing out that all Australians were required to compete under the same flag. Aware that a similar rule violation could lead to being stripped of her medal, Freeman was compliant after winning a silver medal in the 400 at the Atlanta Olympics in 1996. Four years later, however, after she took gold in an emotional 400-meter Olympic final in front of her home crowd in Sydney, Freeman celebrated on her own terms: she ran a victory lap in front of more than 100,000 screaming spectators, carrying both flags—and affirming the sentiment tattooed on her upper right arm: “’Cos I’m free.”

2016: Feyisa Lilesa, Rio de Janeiro

As he closed in on the finish line of the men’s Olympic marathon at last summer’s Rio Games, Ethiopian Feyisa Lilesa and crossed his wrists to form an X. Lilesa came in second place, but the 26-year-old had other things on his mind besides celebrating his first Olympic medal. The X symbol was a gesture of solidarity with Lilesa’s Oromo tribe, the ethnic majority in Ethiopia whose peaceful protests—which were initially a response to government land grabs—have been violently suppressed by state security forces. (According to a from June 2016, more than 400 protestors have been killed in Ethiopia and tens of thousands arrested.) “If I go back to Ethiopia, maybe they kill me,” Lilesa told the . “If not kill me, they put [me] in prison. If not put me in prison, they block me at airport. After that I don’t move anywhere.” Lilesa, who is currently in the United States on a temporary visa for “individuals with extraordinary ability or achievement,” has stated that he wants to return to his family as soon as he can. “I love my people and my country,” he last September. “I don’t want to live in exile. I hope to go home soon once change comes to Ethiopia.”