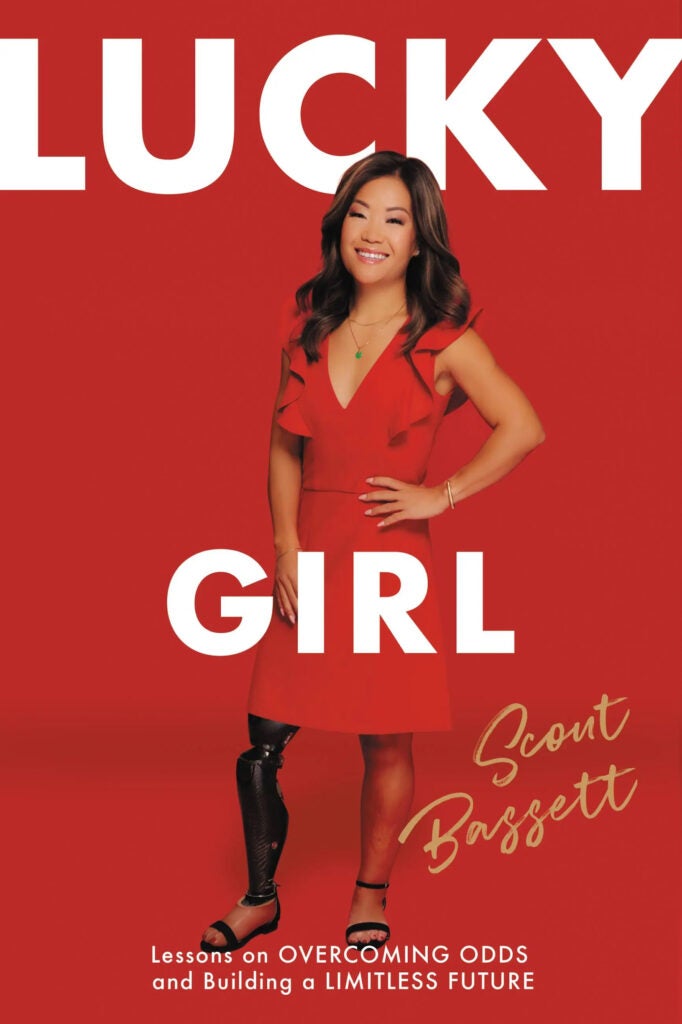

A review of Scout Basset鈥檚 new memoir, 鈥楲ucky Girl: Lessons on Overcoming Odds and Building a Limitless Future鈥�

The post This Paralympian Defined Her Own Future. It Includes Podiums for Others Like Her. appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

Scout Bassett learned an important lesson from an early age: you have to create your own luck.

Born as Zhu Fuzhi (鈥淟ucky Girl鈥� in Chinese), Bassett had to endure years of life鈥檚 cruel irony in her name. As an infant, she survived a fire that resulted in the loss of her leg, as well as the early abandonment by her biological parents.

Part autobiography, part self-help, part social critique, Bassett鈥檚 new book offers a candid view of her life, athletic career, and the seemingly insurmountable obstacles facing athletes with disabilities, especially female athletes. Bassett鈥檚 intention of this book was to help 鈥減osition ourselves to be overcomers鈥攖o be champions鈥o have the fortitude, the grit, the strength, and the mental toughness to do just that.鈥�

Surviving Trauma from Childhood to Adulthood

The book tells Bassett鈥檚 personal journey from a poverty-stricken Chinese orphanage, to a small northern Michigan town, to the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), to the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Paralympics, and to the heart-breaking miss of making the 2021 Tokyo Paralympics team.

Bassett takes a straightforward narrative writing approach to the story of her childhood. Her earliest memory was tainted with hardship and abuse in the orphanage: living on a bowl of rice every day, sleeping in a narrow cot with another orphan, surviving abusive disciplinary acts such as waterboarding. The children never went outside; Bassett never even saw a housecat until after her adoption鈥攐r any animal for that matter.

Following her return to China as a Paralympian after the Rio Games in 2016, Bassett was thrown back into her childhood trauma. The experience of seeing that the orphanage had not changed much鈥攖he same rice for the children, the same permeating urine smell in the building鈥攍eft Bassett with panic attacks long after her return to Los Angeles.

Discovering Belonging Through Running

Being adopted into a conservative Christian family in northern Michigan was her first salvage, though it didn鈥檛 solve her problems of feeling like the other. Bassett never knew what a school was, let alone being the only Chinese student in a majority-white school and the only student of disability.

鈥淕rowing up and being ethnically Chinese, disabled, and adopted, I can鈥檛 remember a time when I didn鈥檛 feel like an other. This dynamic was most obvious at school, with my peers, and the sports teams I was on.鈥�

Even after arriving at UCLA, she felt she wasn鈥檛 fully accepted by some Asian American students. 鈥淏y the time I got to college, I hadn鈥檛 spoken Chinese in over a decade鈥 was raised by a white family鈥or my roommate, I was too culturally white to be Asian,鈥� she writes. 鈥淣ot white enough to be white, mind you鈥ut not Asian enough to be Asian.鈥�

RELATED: Des Linden in Her Masters鈥� Era: 鈥淚鈥檓 Glad I鈥檓 40鈥�

When Bassett discovered running at age 14, it was an indescribable sense of freedom which enabled her to overcome a mindset of victimhood and otherness. 鈥淩unning was really that transformative for me,鈥� she says. 鈥淚 grew in confidence; I grew in self-belief. I held my head just a little bit higher.鈥�

Eventually, through running, Bassett realized that 鈥淏eing an other is a lonely place to be,鈥� and shared a bit of advice: 鈥淒on鈥檛 allow your otherness to lead you to embrace a victim mentality鈥f you鈥檙e reading this right now and you feel like an 鈥榦ther,鈥� here鈥檚 what I鈥檇 say to you: Do not hide. Please, don鈥檛 hide. Don鈥檛 mask who you are鈥our path is not going to look like everybody else鈥檚, but aren鈥檛 you glad?鈥�

Betting on Yourself While Navigating Loneliness

Arriving at UCLA in 2007 started a new chapter for Bassett. Not only was she more exposed to people of all ethnic groups and religious backgrounds鈥攊ncluding more Asian Americans and the LGBTQ community鈥攕he was inspired to pursue Paralympics once a female coach asked her.

Then came more obstacles: a lack of training facilities and lack of coaches who are willing to work with Para athletes. Bassett was undeterred. She started training herself by watching YouTube videos and showing up before dawn to train on the track.

After graduation from college, Bassett went against everyone鈥檚 advice and quit her job at a medical device company. She lived in her car and on people鈥檚 couches to minimize her expenses so she could train full-time. In two years, she competed in the U.S. Championships but came in last. This only made her focus more and double down on her efforts.

The toughest part of Bassett鈥檚 pursuit was not the demanding physical training, but the prevalent sense of loneliness when choosing a path less-traveled. 鈥淭he obvious truth is that loneliness is a natural byproduct of life in an orphanage. But what I鈥檝e learned since is that loneliness is a natural byproduct of life鈥eriod鈥鈥檝e felt lonely on varying levels during almost every season of my life since.鈥�

Even being on the cover of Self magazine and having an made out of her own image couldn鈥檛 cure the everlasting loneliness. Bassett accepted the frequent loneliness and used it to fuel her training. 鈥淪ometimes, that might be to remain isolated so you can grind out a skill, learning, or development,鈥� she writes.

As Steve Magness writes in ,听鈥淲hen we explore instead of avoid, we are able to integrate the experience into our story. We are able to make meaning out of struggle, out of suffering. Meaning is the glue that holds our mind together, allowing us to both respond and recover.鈥�

When Bassett found meaning in speaking for others who often feel lonely because of their 鈥渙therness,鈥� she realized that 鈥渢raining, mentoring, and advocacy have been my answer to loneliness鈥攚hich now doesn鈥檛 feel like loneliness at all.鈥�

This mindset has enabled Bassett to go from finishing last place at the 2012 London U.S. Paralympic track and field trials to competing as a Paralympian at the 2016 Rio Paralympics. After the setback of missing out on the Tokyo Paralympics, she then staged a strong comeback of winning the 100-meter at the 2022 US Nationals.

Building a Legacy on and off the Track

Bassett is unafraid to offer a critical look at the overall lack of systematic support for athletes with disabilities: lack of coaching support, lack of media coverage, and fewer Paralympic events to compete in. It goes all the way to the governing body: Only 4 out of 15 governing positions at the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) are held by women.

But perhaps the biggest hurdles of all are the limited options for Para athletes to continue developing and competing beyond high school. This is one of the intentions Bassett had set up her , to create a pipeline of Para athletes with adequate financial support. 鈥淚鈥檓 not talking about a few thousand dollars,鈥� she writes. We鈥檝e had a partner give a very generous donation that will allow us to give five-figure grants to these girls.鈥�

Christine Yu has also discussed the profoundly inadequate funding in women鈥檚 sports in her book, . 鈥淥n the whole, these institutions (NCAA, etc.) prioritize men鈥檚 sports over women鈥檚 sports.鈥� But on the Para athlete level, systemic support remains nascent. As recently as January 2014, the board of directors of the Eastern College Athletic Conference approved the for student-athletes with disabilities.

RELATED: Can Women Outperform Men in Sports? That鈥檚 the Wrong Question to Ask.

Bassett credits track running star Allyson Felix as one of her inspirations with advocacy. 鈥淎lyson has been a great role model for me as I鈥檝e gotten older in my career. She is the person who helped me to see I鈥檓 so much more than just an athlete鈥鈥檓 more than my wins. I鈥檓 more than my losses. And Allyson set that example for me to follow,” she says.

In creating her Scout Bassett Fund, Bassett hopes to also create other advocates like Allyson Felix and herself鈥攚hole champions on and off the track.

鈥淭he main idea behind the Scout Bassett Fund is to allow these young women to train their way into Paralympic contention. But it鈥檚 also to give these young women a megaphone鈥攖o give them a chance to build their own platforms so they can join their voices with mine to fight for equality and to fight for better representation of disabled females on and off the track.鈥�

The post This Paralympian Defined Her Own Future. It Includes Podiums for Others Like Her. appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

A short film explores the trials of a Team USA athlete struggling to overcome obstacles to compete at an elite level鈥攁nd challenging our notions about what life as a quadriplegic can look like

The post Paracyclist Clara Brown Is Redefining What It Means to Be an Elite Athlete appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

Ability, a听film by and , shares the story of , a Team USA para-cyclist听and Tokyo 2021 participant. Brown is a lifelong athlete, but her circumstances changed forever at age 12: at gymnastics practice, she suffered a traumatic accident that left her with a broken neck and damaged spinal cord. After years of physical and mental obstacles to regain function, Brown continues to adjust as a walking quadriplegic. Her primary motivation? To become an athlete again.

The post Paracyclist Clara Brown Is Redefining What It Means to Be an Elite Athlete appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

From running blades to $16,000 handbikes, high-tech gear helped athletes shatter records in Tokyo

The post Para-Athletes Use Some of the Most Innovative Gear We鈥檝e Seen appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

Just like the Olympics, the Paralympic Games overflow with sporting greatness and remarkable characters. But unlike Olympians, Paralympians use gear for more than just an edge鈥攊t鈥檚 what allows them to compete.听Engineers have come up with ingenious designs to enable athletes with a wide range of injuries and disabilities to perform at their highest level.

In the aftermath of a Paralympics full of , we took a peek at some of the technical equipment used in competitions like triathlon, goalball, track and field, and the infamously brutal 鈥�.鈥�

Running Blades

Estimated cost: $4,000 to $6,000

Running blades are so effective that Blake Leeper, a double amputee, started racing against able-bodied athletes after winning medals at the 2012 Paralympics鈥攈e was barred from Olympic competition because some argued that the blades provide an unfair advantage.

The first running blade was created by Van Phillips, who lost a leg in a water-skiing accident in the 1970s. He was dissatisfied with the prosthetics available at the time, which mimicked human bone structure. Instead, he developed a new concept based on the energy recoil of tendons and ligaments. The Cheetah was launched in 1996 and quickly became widely used by Paralympic athletes.

Today, several companies make running blades, and the bionic limbs are increasingly light, springy, and durable. Some blades are built from up to 90 layers of carbon fiber鈥攕ome thinner than a human hair鈥攆used together in a 3-D printing process.

Blades differ in how much they flex. A sprinter with a fast turnover and low ground-contact time might opt for a stiffer blade; long-distance runners might choose one with more give to reduce impact on the body. They also have significant differences in fit and motion. Above-the-knee amputees can go for a prosthesis with a bionic knee joint that allows for a more familiar up-and-down running action, or one that creates a straight leg from hip to blade and requires a roundhouse stride. Factors like the length of the stump, whether one or both legs have been amputated, and personal preference also figure into the decision.听

For example, unlike some of his rivals, British champion Richard Whitehead runs with a straight-leg prosthesis, meaning his forward momentum comes from hip rotation. While that makes his starts comparatively slow, his dominating speed has led to two gold medals and a silver in the T42 200-meter event, for above-the-knee amputees.

Racing Wheelchairs

Estimated cost: $10,000 to $12,000

With a racing wheelchair, the best para-athletes can reach speeds of around 30 miles per hour (that鈥檚 three miles per hour faster than Usain Bolt). These speeds, on wheels, make the sport more akin to cycling than running. For example, racers often try to take advantage of drafting, tucking in behind a rival until late in an event.听

The effort, cost, and engineering that go into racing chairs also mirror cycling. The chairs are made of lightweight carbon fiber or titanium, and aerodynamics play a key role in design. The big difference of course is that the athlete uses arms instead of legs for power, rotating push rims on the wheels that drive a single gear. In this case the circumference of the push rim dictates how hard the chair will be to move forward. A bigger circumference means it鈥檚 easier to get the chair rolling initially, but a smaller push rim has the advantage of being able to deliver more power per push. (Racers use gloves to protect their hands.)

Steering is another matter. A 鈥渃ompensator鈥� that acts like a rudder is positioned just below the frame and connected to the front wheel. It allows for fine adjustments when rounding a curve on the track or battling wind resistance on the road. Para-athletes spend years perfecting their technique for pushing and rolling at high speeds.听

Beyond the racing events, four other Paralympic wheelchair sports鈥攂asketball, fencing, rugby, and tennis鈥攔equire chairs that are designed for agility rather than straight-line speed. The basketball chair, for example, has wheels pitched steeply inward for ease of turning. They鈥檙e made of titanium or aluminum to withstand the amount of contact they receive during a match, although it鈥檚 not quite as much as the chairs used by rugby players (below).

Rugby Wheelchairs

Estimated cost: $10,000 to $15,000

These wheelchairs deserve a category of their own. Even with a design approach that emphasizes durability, many don鈥檛 last long. That鈥檚 because wheelchair rugby is also known as Murderball.

Wheelchairs used by attackers and defenders tend to differ. Attacking chairs are shorter and have a protective bumper and curved wings to allow them to turn quickly and elude defenders. Defensive chairs have a protruding bumper specifically designed to 鈥渉ook鈥� and hold an attacker, just as you might tackle or block in conventional rugby or on a gridiron.听

Unlike sports that have different classes for athletes with different levels of body function or injury, wheelchair rugby puts all athletes on the field together. Those with less impairment tend to take on offensive roles. It鈥檚 also a mixed-gender sport, and in Tokyo, became the first woman to win rugby gold when Great Britain defeated the U.S. in the title game.

Not surprisingly, chair maintenance is never ending. Axles, tires, and wheels require patching up or complete overhauls after every match. Regular competitors will need entire chair replacements every couple of years.

Handcycles

Estimated cost: $13,000 to $16,000

Paralympic puts together various types and levels of impairment with four categories of gear: handcycles, tricycles, bicycles, and tandem bikes. Tricycles are typically ridden by athletes who can use their legs but have balance issues that prevent them from using bikes. Some athletes can use modified bicycles, while competitors with vision impairments use tandem bikes with guides. Handcyclists use their arms, creating a sport that sits somewhere between cycling and wheelchair racing.听

There are five classes of handcycle racer ranging from H1 to H5, where higher numbers indicate restrictions in lower limbs only and lower numbers indicate impairment in both upper and lower limbs. A handcycle is like a normal bike turned upside down, or a recumbent bike听operated by hand: the athletes hold the pedals with their hands rather than their feet, and custom-made hand grips act like cleats. The brakes are integrated into the hand-pedals. In other ways they are similar to regular bicycles, often with carbon frames, electronic shifters, and models with more than 30 gears.

Aerodynamics are crucial: the low profile allows athletes to cut through the wind at speeds over 40 miles per hour. As the design has evolved, back wheels have shrunk and become increasingly pitched in, decreasing wind resistance (although they can increase rolling resistance through the tires). Check out these stealth of Team USA bikes in Tokyo.听

Specialist Balls

Estimated cost: $70 per ball or set

For several Paralympic ball sports, the key piece of equipment is the ball itself.

Goalball and five-a-side soccer are both played by athletes with visual impairments. Typically, all players are blindfolded to protect the sports鈥� integrity, and in goalball, players lie down and roll the ball by hand. In both sports, the balls have bells embedded in them so the players must use hand-ear coordination. A goalball is the size of a basketball but twice the weight.听

Goalball has no equivalent in the Olympics, and even among Paralympic sports it stands out for the longevity of its star athletes. Asya Miller and Lisa Czechowski, American goalball , have been at it for two decades, and they competed in their sixth Paralympics in Tokyo (they won silver).

Boccia is also unique to the Paralympics but is similar to p茅tanque; each athlete or team throws a series of balls to try to get as close as possible to the jack. It was originally designed to be played by athletes with cerebral palsy, though at the Paralympic level, it includes athletes with other impairments affecting motor skills. The balls are made of leather, for easy gripping, and filled with plastic granules to prevent them from bouncing. They can be kicked, thrown by hand, rolled along the floor, or, for athletes with the most severe impairments, rolled down ramps.

British para-athlete David Smith won a boccia medal in Tokyo, retaining his title as the world鈥檚 best in the BC1 classification (for athletes with severe activity limitations affecting their legs, arms, and trunk). Smith, who has cerebral palsy, which limits his ability to compete in other sports, told The Guardian, 鈥淚 wouldn鈥檛 be a Paralympian without boccia.鈥�

The post Para-Athletes Use Some of the Most Innovative Gear We鈥檝e Seen appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

The Tokyo 2020 Paralympics get underway this week. Here鈥檚 who and how to watch.

The post Everything You Need to Know About the Paralympics appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

If the roller-coaster Tokyo 2020 Olympics did anything, they stoked our enthusiasm for the return of global sports with their rivalries, , superhuman athletic feats, and moments of that can make a rugby player cry. The Tokyo 2020 Summer Paralympics kick off on August 24, and they promise to feature just as much set against a backdrop of . If witnessing dedicated athletes realize their dreams gives you some joy amid all the uncertainty, it鈥檚 easy to see these games as the sporting event of the summer.

Tokyo is the first city to host the Summer Paralympics twice; back in 1964, 378 athletes competed in nine sports. This year, 4,400 athletes from about 170 nations will compete for gold in 22 different sports. Some are familiar events like swimming and track and field; others, like goalball or boccia, are wholly unique to the Paralympics.

Badminton and taekwondo will make their debut and replace sailing and seven-a-side soccer. Additionally, medals this year will include circular indents on the rim (one for gold, two for silver, three for bronze) to better serve visually impaired medalists. With COVID-19 cases still surging in Japan, the stands will be mostly empty (though this might not bother athletes during events like goalball, which requires silence so visually-impaired athletes can hear the jingling ball鈥檚 position on the court).

Here鈥檚 everything you need to get primed for the games鈥攁nd stay tuned for continuing coverage.

Paralympics History

The first version of what would become the Paralympics debuted just after World War II. After fleeing Nazi Germany, doctor Ludwig Guttman founded the Stoke Mandeville Games in 1948 for British veterans with spinal cord injuries. The coincided with the Summer Olympics Opening Ceremonies in London; 16 men and women competed in a single event (archery).

Dutch veterans joined in 1952, kicking off an international competition that now trails only the Olympics in size and scope. The Summer Paralympics debuted in 1960 in Rome. Every four years since, winter and summer versions have taken place a few weeks after the Olympics conclude.

How to Watch the Paralympics

This year, the Paralympics will make its prime-time debut on NBC on Tuesday at 7 A.M. ET. Over 200 hours of live and delayed events will be broadcast across NBC, NBC Sports Network, and the Olympic Channel, while 1,000 more hours will stream through NBC鈥檚 streaming options like Peacock. Get the and a .

Classification System

The Paralympics classification system is at the heart of all Para sports competition: it both determines eligibility and levels the playing field. The latter is important given the diverse range of impairments, so that winners can be determined by skill, fitness, and performance in any given event. In goalball, for instance, players are all required to wear eyeshades so athletes with different levels of visual acuity can play together while maintaining the same level of competitive advantage.

There are ten different impairments that determine if an athlete is eligible to compete in the Paralympics: impaired muscle power, impaired passive range of movement, limb deficiency, leg length difference, short stature, muscle tension, uncoordinated movement, involuntary movements, vision impairment, and intellectual impairment.

The layers of classification can be complex, and are often customized for each sport. Track and field, for instance, comprises 32 different classes for events, ranging from T/F11, T/F12, and T/F13 (for different levels of vision impairment) to T/F34 (for athletes who compete in a wheelchair). Cycling is divided into four classes: C (cycling), H (handcycling), T (tricycle), and B (tandem for the visually impaired). A subclass numbering from one to five is then appended to indicate severity of impairment (C1, C2, C3, C4). But classification is not always standardized across the sport: B1, B2, and B3 tandem all have a sighted pilot rider with them, and thus all compete in the same event. (In sports that require them, the guides or pilots share medals.)

Other sports, such as basketball, include players of varying abilities and apply a point value to each player depending on level of impairment.

to Paralympics sports classification.

Athletes to Watch

The United States鈥� Paralympic roster of 234 includes 129 returning Paralympians and 51 champions. Here are some of Team USA鈥檚 brightest stars.

Tatyana McFadden

Paralyzed from the waist down since birth because of spina bifida, this 32-year-old already has 17 Paralympic medals, including six from Rio. She won the 鈥済rand slam鈥� of wheelchair marathons (London, Boston, New York, and Chicago) in 2013. McFadden has come a long way since she began 鈥渟cooting鈥� around sans wheelchair to keep up with friends in an orphanage in St. Petersburg, Russia. She will compete in a slew of events in Tokyo, including the 100-meter, 400-meter, 800-meter, 1,500-meter, 5,000-meter, 4×400-meter relay, and marathon wheelchair events. McFadden is also one of nine athletes featured in the Netflix documentary , which she co-produced.

Jessica Long

With 23 medals鈥�13 of them gold鈥擩essica Long is the second-most decorated Paralympian from Team USA and a dominant force in the pool. Born in Siberia with fibular hemimelia, to amputate her legs below the knee as a child, shortly after her adoption by a U.S. family. She got her start swimming in her grandparents鈥� pool, where she pretended to be a mermaid. Now, after training for years with Michael Phelps, she has a new nickname: 鈥淎quawoman.鈥� Look for her to crush again in the 50-meter freestyle, 100-meter freestyle, 400-meter freestyle, 100-meter backstroke, 100-meter breaststroke, 100-meter butterfly, 200-meter individual medley.

Allysa Seely

Seely was a nationally ranked triathlete when a diagnosis of chiari II malformation, basilar invagination, and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome led to neurological difficulties, brain and spine surgery, and an eventual below-the-knee left leg amputation. Three years later, she won gold in triathlon鈥檚 Rio debut, which she鈥檒l defend in Tokyo.

Brad Snyder

A former swim team captain at the U.S. Naval Academy, Snyder was injured by an explosive device while serving in Afghanistan. The explosion left his limbs intact but required the removal of his eyes. He took gold in the Men鈥檚 S11 100-meter freestyle in the 2012 London Paralympic Games one year to the day after losing his vision. He switched to triathlon in 2018, and hopes to medal in Tokyo.

David Brown

Known as the 鈥渇astest blind man in the world,鈥� David Brown holds the world record in the 100 meters (T11, 2014) alongside his guide Jerome Avery. They nicknamed themselves 鈥淏rAvery鈥� and won gold in the 100 meters in Rio. The pandemic disrupted the duo鈥檚 training regimen, which requires close proximity, but they remain medal favorites in Tokyo.

Oksana Masters

Masters was born three years after the Chernobyl disaster in Ukraine, which likely caused the birth defects that led to eventual amputation of both legs and reconstructive surgery for thumbless hands and webbed fingers. But now she鈥檚 an aspiring multi-season master: after winning bronze in rowing in London, Masters took gold in Nordic skiing in Pyeongchang before adding hand-cycling to her summer portfolio ahead of Rio, where she narrowly missed the podium in road (4th) and track (5th) races. Tokyo could finally bring a summer gold to match winter.

Melissa Stockwell

In April 2004, Melissa Stockwell lost听a limb in active combat when a roadside bomb exploded next to her vehicle. She was awarded a Purple Heart and Bronze Star, and in 2008 became the first Iraq War vet to qualify for the Paralympics as a swimmer in Beijing. She switched to paratriathlon and took bronze in Rio behind fellow Team USA members Allysa Seely and Hailey Danze, who she will challenge in Tokyo.

The post Everything You Need to Know About the Paralympics appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

Do high-tech prosthetics give runners a competitive advantage?

The post The Science and Controversy of Running Blade Prosthetics appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

In the 1970s television show The Six-Million Dollar Man, a severely injured test pilot is rebuilt with nuclear-powered bionic limbs. These cybernetic parts allowed the pilot to suddenly become superhuman鈥攖he new-and-improved Colonel Steve Austin could not only run faster than a car, he could lift said car with just one bionic arm (which, as viewers discovered in episode six, also contained a Geiger counter to save the world from doomsday). Every week, the opening credits would intone with great seriousness:

Gentlemen, we can rebuild him. We have the technology. We have the capability to make the world鈥檚 first bionic man. Steve Austin will be that man. Better than he was before.

Better… stronger… faster.

The Six-Million Dollar Man could have been an icon for inclusivity鈥攑eople with disabilities can do cool things! Instead, the takeaway was that artificial body parts are bionic wonders, increasing ordinary human powers beyond the realm of possibility. From the action-adventure series Bionic Woman, which featured Steve Austin鈥檚 cybernetic counterpart, Jamie Sommers, to the whatzits and whirlygigs within the arms of the animated Inspector Gadget, pop culture has created a fantastical story of phenomenal feats contained within ordinary prosthetic limbs. Even today, prosthetics are largely misunderstood, which impacts the way users are treated in a variety of personal and professional settings.

Perhaps no better example of this effect is Blake Leeper鈥檚 recent lawsuit against , the governing body of track and field. The American sprinter, who was born with both legs missing below the knee, sued for the right to compete against runners with biological legs at the 2021 Tokyo Olympics. The eight-time Paralympic Track and Field medalist, world record holder, and three-time American record holder was told his prosthetic legs were an 鈥渁rtificial competitive advantage鈥� under , which intends to prevent disabled athletes from competing against able-bodied athletes with mechanical aids that overcompensate for the loss created by a disability.

Leeper isn鈥檛 the first athlete with a limb difference to sue for the right to compete against athletes with biologically intact limbs. South African sprinter Oscar Pistorius filed a similar lawsuit after being banned from able-bodied competition in 2008. The prevailing belief was that Pistorius鈥檚 prosthetics, known as 鈥淔lex-Foot Cheetahs,鈥� enabled him to use less energy than non-amputee athletes while covering the same distance, and therefore run faster. Pistorius appealed the ban and won, making history as the .

Still, no clear precedent was set for future athletes, and in 2019 Leeper found himself in the same fight as Pistorius. In his appeal to compete against all athletes, Leeper was tasked with the burden of proving he was not, in fact, a bionic man.

The post The Science and Controversy of Running Blade Prosthetics appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>