From a music-centric journey across the northern U.S. to a national park-studded road trip through the heartland, we鈥檝e got itineraries to get you started with plenty of space for your own adventures.

The post Three Epic Cross-Country Road Trips to Start Planning Now appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

No adventure compares to driving across the United States. I鈥檒l never forget my first coast-to-coast drive. It was two friends and me, post college, in a beat-up Subaru loaded with everything I owned. We took the long way home, starting in the farmlands of Vermont and making out-of-the-way pitstops for hiking in the Great Smoky Mountains听of Tennessee, dining at legendary barbecue spots across Mississippi, and listening to live music in New Orleans. We drove west, climbed the highest peak in Texas, ate green chile in New Mexico, and stared into the Grand Canyon in Arizona. Most nights, we slept in a tent and dreamed of where the next day would take us. When we finally crossed the California state line toward our final destination, I remember feeling like I wanted to stay on the road forever.

The cross-country road trip is an American rite, a true pilgrimage where you can plan only so much; the rest will unfold wherever the road goes. These three epic journeys have starting and ending points, as well as some spots that may be worth pulling over for along the way, but what you make of the trip鈥攁nd what you ultimately take away from it鈥攊s up to you.

We鈥檝e picked three routes on major highways that cross the country (for a Southwest specific guide, explore our seven best road trips of that region), but along the way, we鈥檝e provided suggestions for detours and byways that get you off the beaten path and out of your car to stretch your legs, experience local culture, and see the sights you鈥檒l be talking about all the way to your next stop. You鈥檒l pull over for things like meteor craters, giant art installations, and donuts. With visits to roadside national monuments, waterfalls, and hot springs鈥攁nd with stays at unique hotels, campsites, and cabins along the way, these road trips aren鈥檛 just a long drive, they鈥檙e an incredible adventure waiting to happen.

The Music Lover鈥檚 Journey: Boston, Massachusetts, to Seattle, Washington

Route: Interstate 90

Distance: 3,051 miles

This northern route across the U.S. follows Interstate 90 from east to west, passing by major cities like Cleveland, Chicago, and Minneapolis. But you鈥檒l also touch on some of the country鈥檚 coolest wild spaces, like the Berkshires of western Massachusetts, the Black Hills of South Dakota, and Yellowstone National Park in Montana. Inspire your road trip playlist by checking out the outdoor music venues and festivals throughout this route.

Pitstop: The Berkshires, Massachusetts

Hop on Interstate 90 in Boston and point it west. Your first stop is the Berkshires, a mountainous region filled with charming small towns 120 miles west of Boston. Go for a hike in , then pick up a tangleberry pie or farm-fresh apples from market in Great Barrington. In Stockbridge, the is worth a stop to learn more about American painter Norman Rockwell, who lived in the area, or check the performance calendar at , home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, for major touring acts in this pastoral outdoor music venue. It鈥檚 worth the 30-mile detour off the highway to North Adams to post up for a night or two at (from $194), a revamped motor lodge that hosts guided hikes, live music, and pop-up dinners.

Must See: Niagara Falls, New York

Peel off the highway in Buffalo, New York, for a visit to , America鈥檚 oldest state park and home to its three namesake waterfalls. Grab a yellow poncho and a ticket ($14) to view the falls from below at the observation decks.

Pitstop: Saint Charles, Iowa

Take a detour to visit Saint Charles, Iowa, home to the four-day held each August on a 350-acre plot of grassland. This year鈥檚 headliners include Tyler, the Creator, Kacey Musgraves, and Lana Del Ray. You can camp on site during the festival and hop a free shuttle into nearby Des Moines. If you can鈥檛 make the show, Des Moines still delivers, with 800 miles of trails to explore on foot or bike, including the paved 25-mile , a converted rail-trail with an iconic bridge that鈥檚 lit up at night over the Des Moines River valley. rents bikes.

Pitstop: Black Hills, South Dakota

There鈥檚 tons to see in the Black Hills of South Dakota, including famous highlights like and , as well as lesser known gems like the third longest caves in the world at or the annual buffalo roundup each September in . Grab donuts for the road from , a famed roadside attraction. Stay in a canvas tent among ponderosa pines at (from $179), outside the town of Keystone.

Stretch Your Legs: Devils Tower National Monument, Wyoming

It鈥檚 not far off I-90 to reach , a geologic monolith with deep roots to indigenous cultures in the northern plains and the country鈥檚 first national monument. Parking and trails can be crowded here, so skip the main lot and hike the 1.5-mile instead鈥攊t鈥檚 less busy and still has good views of the tower.

Pitstop: Bozeman, Montana

Post up at the (from $189) in downtown Bozeman, which has on the property. Stroll Main Street, then take a walk up through Burke Park, a few blocks away, for a nice view of town. It鈥檚 about an hour and 20 minutes drive to reach the north entrance to , known for its geysers and 2.2 million acres of wilderness. If you鈥檙e on the road for music, the in nearby Big Sky takes place in early August.

Pitstop: Coeur d鈥橝lene, Idaho

Home to Lake Coeur d鈥橝lene as well as dozens of smaller lakes, you鈥檒l want to stop in Coeur d鈥橝lene, Idaho, for a swim or a paddle. rents kayaks and paddleboards. on the southern end of Lake Pend Oreille has cabins and campsites (from $48), a , and access to 45 miles of trails for biking and hiking.

Must See: The Gorge Amphitheater, Washington听

Music听breaks up the drive, and there鈥檚 no better place to see live music outdoors in this part of the country than the in Quincy, Washington. There鈥檚 on-site camping during shows and an upcoming lineup that includes Billy Strings and Tedeschi Trucks Band.

Stretch Your Legs: Snoqualmie Pass, Washington

Hike to stunning alpine lakes on Snoqualmie Pass, just an hour outside of Seattle on I-90. You鈥檒l need a $5 to access most of the hikes in this area. The 2-mile follows the Snoqualmie River to a 70-foot waterfall. For a more stout climb, the 8.5-mile roundtrip hike to in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness is a real gem.

Final Stop: Seattle, Washington

Celebrate the end of an epic journey by watching the sunset over the Olympic Mountains and dipping your toes into Puget Sound from Seattle鈥檚 . Stay in the heart of downtown at the (from $189) and you can browse fresh produce and maker鈥檚 stalls outside your door. The 10-mile paved sits right along the waterfront. Want more live music to cap off your trip? The is downtown Seattle鈥檚 coolest music venue.

The Best National Parks Road Trip: San Francisco, California, to Washington, D.C.

Route: Interstate 80 and Interstate 70

Distance: 2,915 miles

Travel across the heartland of the U.S. on this iconic route along I-80 and I-70, passing through stunning western mountain ranges like California鈥檚 Sierra Nevada, Nevada鈥檚 Ruby Mountains, Utah鈥檚 Wasatch, and Colorado鈥檚 Rockies. You鈥檒l visit the great national parks across southern Utah听and hit cities like Denver, Colorado; Kansas City and St. Louis, Missouri, and Columbus, Ohio, before landing in the country鈥檚 capital.

Pitstop: Lake Tahoe, California

Depart San Francisco on Interstate 80 heading east, leaving the shores of the Pacific Ocean to begin a steady climb toward the mountains of the Sierra Nevada range.听, in the roadside town of Auburn, has good burgers and homemade pies for the road. Lake Tahoe is your first stop, a short but worthy departure from the highway. Stay at the new听 (from $138), which opens in March, and you鈥檒l be steps from the lake. Rent bikes at听 to pedal the world-class singletrack along the听 or grab a paddleboard from听. Don鈥檛 miss dinner at the newly opened, featuring eclectic dishes and locally-sourced ingredients.

Pitstop: Ruby Mountains, Nevada

听There鈥檚 not much on Interstate 80 as you cross Nevada between Reno and Salt Lake City鈥攅xcept for the Ruby Mountains, which spike straight up from the desert floor of the Great Basin. In the winter,听 offers heli-ski access to 200,000 acres of rugged terrain. In the summer, there鈥檚听. Stay at Ruby Mountain Heli鈥檚听 or one of their two mountainside yurts (from $190).

Must See: Great Basin National Park, Nevada

For a national park detour, consider visiting听, which has one of the darkest skies in the world for stargazing. Near the entrance to the park, the听 make for a great overnight stop and snack resupply station.

Pitstop: Moab, Utah

In Salt Lake City, you鈥檒l say goodbye to Interstate 80 and head south to meet up with Interstate 70, but not before spending time to explore the Mighty Five national parks that made southern Utah famous: Arches, Bryce Canyon, Canyonlands, Capitol Reef, and Zion. You could spend weeks here鈥攐r just a couple of days. Be sure to book a self-guided or ranger-led hike in the slot canyons of the in Arches National Park and get a permit to hike the exposed rocky cliffside of in Zion National Park. (from $129) makes for a great base camp, or there鈥檚 .

Stretch Your Legs: Glenwood Canyon, Colorado

Get back on I-70 and make your way into Colorado, where scenic Glenwood Canyon makes for a stunning drive along the Colorado River. The paved parallels the highway for over 16 miles, making for an easy biking or running destination. Afterward, stay for a soak in the . A new 16-suite boutique hotel called Hotel 1888 is opening near the hot springs this summer.

Pitstop: Breckenridge, Colorado

Spend the night at (from $320), which opened in early 2025 at the base of Peak 9 at, home to skiing and snowboarding in the winter and biking and hiking come summer. Stroll the charming Main Street of downtown Breck and don鈥檛 miss a visit to the , a 15-foot-tall wooden art installation now located on the town鈥檚 Trollstigen Trail.

Must See: Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

It鈥檚 not exactly on the way, but this adventure clearly detours for national parks, so make the trek north to Rocky Mountain National Park, a quiet, snowy paradise in the winter and a fishing and backpacking mecca in the warmer months. The short hikes to and are popular among families. For experienced mountain travelers, Longs Peak is the park鈥檚 most famous 14er鈥� leads guided treks to the peak. Stay overnight in Denver before you head into the plains: (from $189), the country鈥檚 first carbon positive hotel, opened in Denver鈥檚 Civic Center Park late last year.

Stretch Your Legs: Monument Rocks, Kansas

There鈥檚 a on an 80-foot easel鈥攐ne of three in the world鈥攙isible from the highway in the town of Goodland, Kansas. Then, pull over for 50-foot-high fossil rock outcroppings and limestone spires on the Kansas prairie at , which is on private land that鈥檚 open to the public south of Oakley, Kansas, right off I-70. 国产吃瓜黑料 of Topeka, you can visit the , a former school site that commemorates the historic end of racial segregation in public schools.

Pitstop: St. Louis, Missouri

Next stop on your national park tour? The of St. Louis. You can ride a tram 630 feet to the top of the arch, walk the palatial grounds beneath the architectural wonder, or admire the arch from a riverboat cruise along the Mississippi River. The (from $149) is housed in a historic shoe company building and has a rooftop pool and restaurant overlooking the city. is a public market with a food hall, retail shops, and live music, and don鈥檛 miss brunch amid a plant nursery at the city鈥檚 .

Pitstop: Cuyahoga Valley National Park, Ohio听

Ohio has but one national park and it鈥檚 worth the detour to visit: has paddling along the Cuyahoga River, 20 miles of multi-use pathways along the Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail, and 125 miles of hiking trails through woodlands and wetlands. There鈥檚 no camping within the national park but has tent camping (from $40) nearby or the (from $200) is within the park and on the National Register of Historic Homes.

Final Stop: Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park, Maryland

End your national parks tour of the U.S. with a visit to the . The C&O Canal follows the Potomac River for 184 miles from Cumberland, Maryland, to Washington, D.C. It makes for a great walk or bike ride. Pitch a tent at one of the free hiker or biker campsites or pull your car up to one of a handful of drive-in sites (from $10). Or you can stay in a (from $175) along the canal.

The History Buff鈥檚 Tour of the U.S.: Los Angeles, California, to Charlottesville, Virginia

Route: Interstate 40

Distance: 2,696 miles

This pilgrimage sticks to one highway only for most of the way: Interstate 40, which starts in the Mojave Desert of California and crosses the southern portion of the U.S., over the Rocky Mountains and through the Great Plains and the Appalachian Mountains. It traverses Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina. Much of the western route parallels the historic U.S. Route 66, so it feels like a throwback to another era, a perfect journey for those who love learning about our nation鈥檚 past.

Pitstop: Mojave National Preserve, California

听You can watch a drive-in movie, visit a ghost town, or hike through lava tubes in . You can鈥檛 miss a visit to , an hour away, for stellar stargazing, rock climbing, and 300 miles of hiking trails. Stay in an adobe bungalow at the centrally located (from $195), which has an on-site farm, restaurant, and picnic lunches to go.

Stretch Your Legs: Lake Havasu, Arizona

will deliver you a kayak or paddleboard to explore the waters of the , once a major tributary on the lower Colorado River and one of the last ecologically functioning river habitats in the southwest.

Pitstop: Flagstaff, Arizona

Post up at the (from $109) in Flagstaff, Arizona, and then go explore the sights around Flagstaff, including , an hour and a half north. The 3-mile , along the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, makes for a mellow stroll. The on Route 66 in Flagstaff used to be a historic taxidermy shop and is now a popular bar for country music and line dancing.

Must See: Meteor Crater National Landmark

Yep, you鈥檙e pulling off the highway to see this: The most preserved meteorite impact site on earth is right off I-40 near Winslow, Arizona. For a $29 admission at the , you can sign up for a guided hike of the crater鈥檚 rim.

Stretch Your Legs: Continental Divide Trail; Grants, New Mexico

听You鈥檙e passing from one side of the Continental Divide to the other: Might as well get out of the car and go for a trail run or hike along the Continental Divide Trail, which crosses Interstate 40 near the town of Grants, New Mexico.

Pitstop: Santa Fe, New Mexico

Take a detour off I-40 in Albuquerque to spend a night or two in Santa Fe, the highest elevation capital city in the U.S., which sits at 7,000 feet in the high desert. Splurge on a night at (from $645), a full-service retreat in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristos. For art and history buffs, the and the are well worth a visit.

Must See: Palo Duro Canyon State Park, Texas

You鈥檝e already seen the actual Grand Canyon, so now it鈥檚 time to see the Grand Canyon of Texas, in , 25 miles outside of Amarillo. The park has camping and cabins, an 800-foot-deep canyon, mountain bike trails, and an outdoor stage where actors perform a Texas musical.

Pitstop: Hot Springs, Arkansas

You鈥檒l come to Hot Springs for the historic bathhouses and modern-day spa resorts. At , you can soak in one of two original bathhouses. Want to learn about some of the country鈥檚 most infamous criminals? , in downtown Hot Springs, has exhibits on Al Capone and Owen Madden. The (from $169) is housed in a centrally located historic building. Don鈥檛 miss: is the only brewery in the world that uses thermal spring water for its beers.

Must See: Crater of Diamonds State Park, Arkansas

If you鈥檙e into geologic history, add a visit to Arkansas鈥� , where you can dig for minerals and gems in a 37-acre field on an eroded volcanic crater. (And yes, notable diamonds have been discovered here.)

Pitstop: Nashville, Tennessee

From the music scene to the foodie paradise, you might never want to leave Nashville. Stay in one of eight suites in a 19th century mansion at (from $306), where wood-fired pizzas are served in the backyard. The currently has exhibits on Luke Combs and Rosanne Cash. Go for a walk or run in or take a guided bike tour of the city鈥檚 murals and street art with .

Pitstop: Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee

In Great Smoky Mountains National Park, on the border of North Carolina and Tennessee, you can hike to waterfalls like Mouse Creek Falls or Mingo Falls, fish for brook trout, or bike the 11-mile Cades Cove Loop Road, which is closed to cars on Wednesdays from May through September. The coolest place in the park to sleep? The (from $189), located atop Mount Le Conte and accessible only via foot. Open from March through November, the lodge requires at least a five-mile hike to reach. Bookings for this year are mostly snatched up already, but you can get on the waitlist or plan ahead for next year.

Final Stop: Blue Ridge Parkway, North Carolina

Your trip finale comes in the form of ditching Interstate 40 in exchange for a meandering drive along the , a 469-mile stretch through the Appalachian Mountains and one of the most scenic roadways in America. You鈥檒l stop to see Whitewater Falls, the east coast鈥檚 tallest waterfall at 411 feet, and the rugged Linville Gorge Wilderness. Stay nearby at (from $175), which opened in the mountain town of Highlands in 2024 with a supper club and Nordic spa. They鈥檒l also book you outdoor excursions, ranging from rock climbing to fly fishing.

Megan Michelson is an 国产吃瓜黑料 contributing editor who loves long drives, even when her two children are whining in the backseat. She has recently written about Airbnb treehouses, the most beautiful long walks in the world, and the 10 vacations that will help you live longer.听

The post Three Epic Cross-Country Road Trips to Start Planning Now appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

A rural road relay offers the author a chance to return home and consider important questions, like: Who has the aux in the support van and where did they find this weird club track?

The post Running 339 Miles Through Rural Iowa Is More Fun than You’d Expect appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

Around 3:00 A.M. on a Sunday morning in eastern Iowa, I am behind the steering wheel of a van pulled over to the side of a county highway, eating from a bag of Fritos Honey BBQ Flavor Twists and drinking a can of Starbucks DoubleShot. A man I just met a couple days ago is running toward the van alone on the shoulder of the road, illuminated by a headlamp and a lighted vest. In a few seconds, he will reach us, and another man I just met will hop out, bump fists with him, and run down the road, and I will move the van one mile ahead in the same direction and pull over. Then I will stop eating Fritos Flavor Twists, turn on my headlamp, and wait on the shoulder of the road for my fist bump.

When it鈥檚 my turn, I run away down the shoulder, shoes slapping the asphalt next to the painted white line. I will see one other car come down the road for the entire eight and a half minutes I鈥檓 running.

Josh told me yesterday morning that one of the fun things about running by yourself out in the country during Relay Iowa is that you can turn your headlamp off, and there鈥檚 usually enough light from the stars and moon that you can see where you鈥檙e running. I said, 鈥淵eah, I used to flip off the headlights in my piece-of-shit S10 pickup while I was driving Iowa county roads at night when I was younger, which was 鈥� 20-plus years ago now?鈥�

Josh is running in Luna sandals, with toe socks underneath. But one night during an earlier Relay Iowa year, he was wearing sandals with no socks, and running alongside a friend. They clicked off their headlamps to run in the dark.

鈥淚 definitely grazed a dead raccoon with my bare toes,鈥� Josh said.

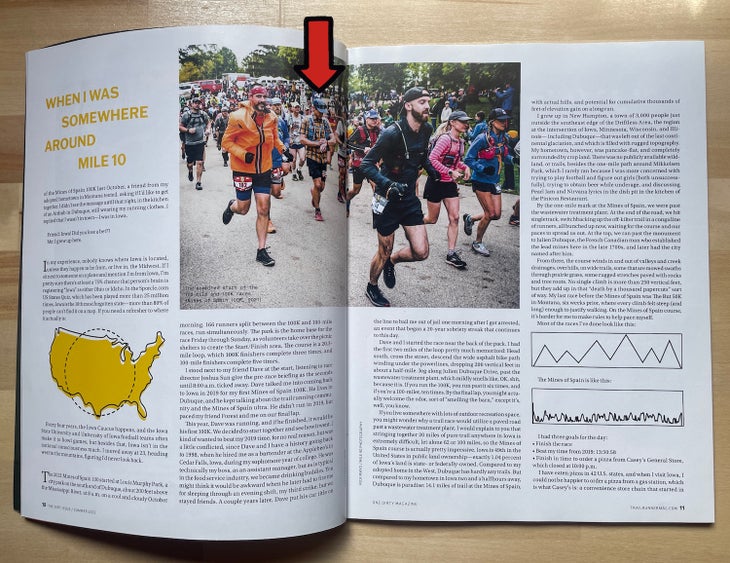

The first Relay Iowa mile I ran was Mile 18 of the 339-mile course. I stood on the gravel shoulder of the road in a light rain as 17-year-old Parker, our team鈥檚 youngest member, flew down the asphalt next to the painted white line. He held out the baton as he coasted to a stop, and I grabbed it and started running. I was ready to go, or at least get a few miles in, after wondering what this would be like for the past few weeks. Was I nervous? I mean, I knew I could run one mile. The real question was: Could I run 30-something miles, one at a time, over 52 hours?

Another question: You left the Mountain West just when the weather was just starting to get really nice at the beginning of June, to travel to Iowa to run a relay across the state on county highways?

There was absolutely no reason to run fast. Relay Iowa is not a race. Nobody 鈥渨ins.鈥� This year, 21 teams started the relay in Sioux City, Iowa, on a hill overlooking the Missouri River, Iowa鈥檚 western border, on Friday morning. We鈥檇 all finish sometime on Sunday. Nobody on our team was concerned with running particularly fast, because surviving to complete all (or at least the majority of) your allotted miles was more important鈥攊.e., if you took off fast and pulled a muscle or wrenched an ankle on your first (or second or third or fourth) mile of your roughly 35 assigned miles for the weekend, the rest of the team would have to pick up your miles. If one team member gets injured, not a big deal, but if two or three or four people get injured, then it starts to be a big lift for everyone else. Again, no reason to run fast.

I ran fast. My mile was pretty flat, it was on asphalt, I was wearing cushy road running shoes, maybe I was just a little excited to run very short distances (something I never do). But I ran a fast-for-me 7:45 down the Moville Blacktop, turned left onto County Road D38 toward the Woodbury County Waste Transfer Station, a semi passed me, the 96 percent humidity hung on me like an old sweatsuit, and very quickly, I saw our van, hazard lights flashing, and Greg, standing across the road from it, waiting for me to give him the baton. I jumped in the drivers鈥� seat of the van and started driving.

The reason I came back for this is: In 2018, started telling me about an ultramarathon in Dubuque, Iowa, called the Mines of Spain 100. Dave has introduced me to many great things throughout our 20-plus-year friendship, like Fugazi, Kind of Blue, and several restaurants, so I thought I鈥檇 give the 100K version of the race a try in 2019. It was surprisingly hilly, early fall was a great time to be back in Iowa to visit my parents, and the race was really fun. So I did it again in 2021, and got to know the race director, Josh Sun, a little more when I wrote .

As it turns out, Josh is very talented at creating community around running, or getting people on board with his ideas that involve running. This is not his day job, but rather a hobby/side gig he is very passionate about, in a very laid-back way. Some of the things he has brought to life, as a race director and/or Friend Who Has A Fun Idea:

- The Mines of Spain 100, a 100K and 100-mile race in Dubuque鈥檚 Mines of Spain Recreation Area, which has only 21 total miles of maintained trails

- The , a 50K and 100K race around the streets of Davenport, Iowa, in which convenience stores serve as checkpoints/aid stations

- The Schuetzen NEIN! Hour Endurance Run, a nine-hour race that takes place entirely on a 0.85-mile loop with 125-150 feet of elevation gain per loop, and is a nine-hour race instead of the more common 12-hour race because the park was founded by German immigrants and 鈥渋t鈥檚 fun to yell 鈥榥ein!鈥欌€�

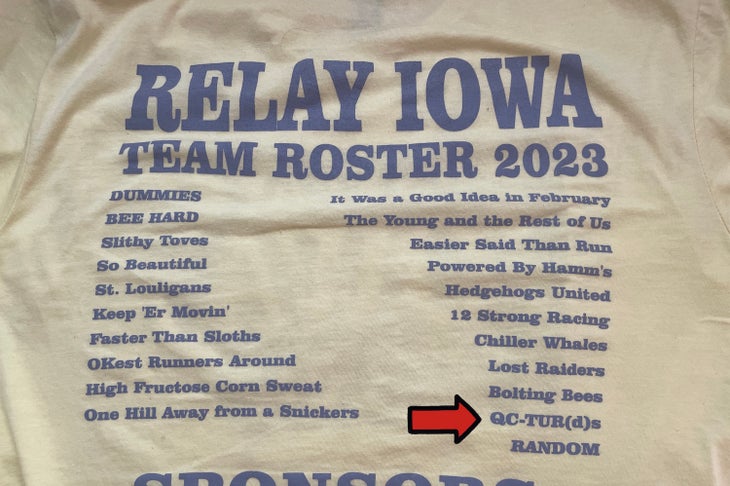

- The Quad Cities Trail and Ultra Runners group, aka the QC-TUR(d)s, which, among other things, celebrates 鈥淭UR(d)smas,鈥� a challenge in which participants compete to attain 25,000 feet of elevation gain in the shortest horizontal distance, during the first 25 days of December鈥攊n the Quad Cities, a region at the intersection of Iowa and Illinois, an area that is not exactly flat, but also not mountainous

QC-TUR(d)s was also our Relay Iowa team name, which means it was printed on the back of not just our t-shirts, but the t-shirts of everyone who participated in Relay Iowa:

We didn鈥檛 interact that much with other teams, besides a few honks, waves, and brief words of encouragement to other runners, so I would go the entire weekend without anyone asking, 鈥淗ey, are you a TUR(d)?鈥� something that would have worked really well when writing a story about something like this. I mean, in a sense, aren鈥檛 we all? Sometimes.

Our team鈥檚 average age is 39.5. Josh is 37 years old, Parker is 17, Steve (Parker’s dad) is 37, Drew is 32, Brian P. is 44, Brian B. is 48, Andy is 40, Mitch is 38, Greg is 58, and I鈥檓 44. Collectively, the TUR(d)s have dozens of ultramarathon finishes, including 100-milers. Which is not saying we are qualified to do something like Relay Iowa, but it doesn鈥檛 hurt.

I described Relay Iowa to some people as, 鈥淟ike Hood to Coast, but instead of Hood and the coast, it鈥檚 the Missouri River to the Mississippi River.鈥� Josh tells people that it鈥檚 like RAGBRAI (the weeklong group bike ride across Iowa that will celebrate its 50th year in 2023), except running instead of bicycling. Also, I would point out, much smaller than RAGBRAI, with around 200 participants compared to RAGBRAI鈥檚 ~10,000 (which on some days has swelled to more than 30,000 people).

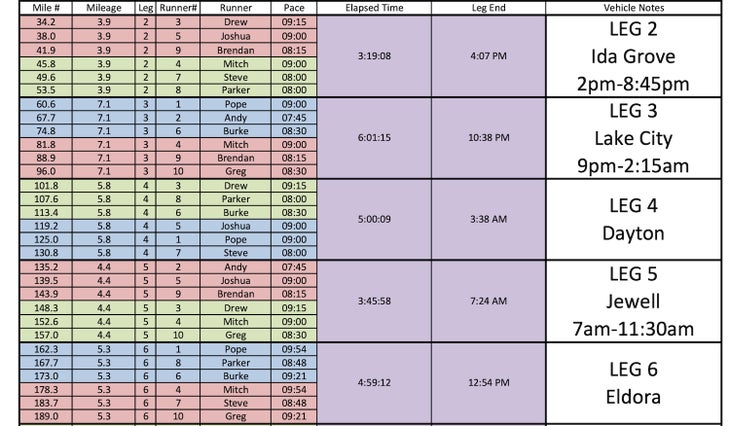

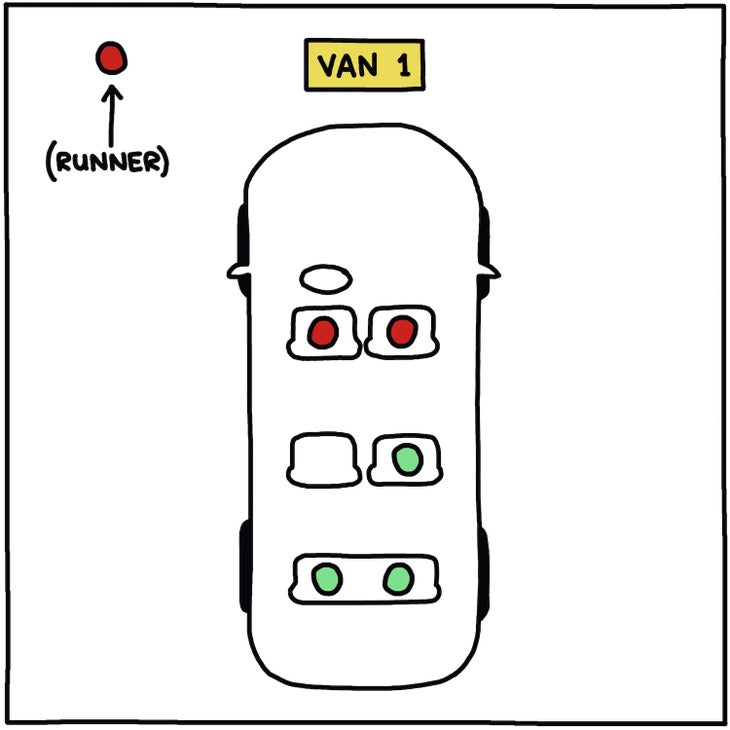

Until the day before the Relay started, I didn鈥檛 really know how it worked. I assumed we鈥檇 just rotate through our 10 team members, running one mile at a time. So if we all ran 9-minute miles, each rotation would take 90 minutes. I鈥檇 have 9 minutes of running, followed by 81 minutes of rest, then repeat, for 52 hours straight. Then Josh sent me a color-coded spreadsheet. A screenshot from the middle of the spreadsheet:

So then I thought, 鈥淥h, OK, looks like I run 3.9 miles, then rest, then run 7.1 miles, then rest 鈥︹€� Which was also not the case.

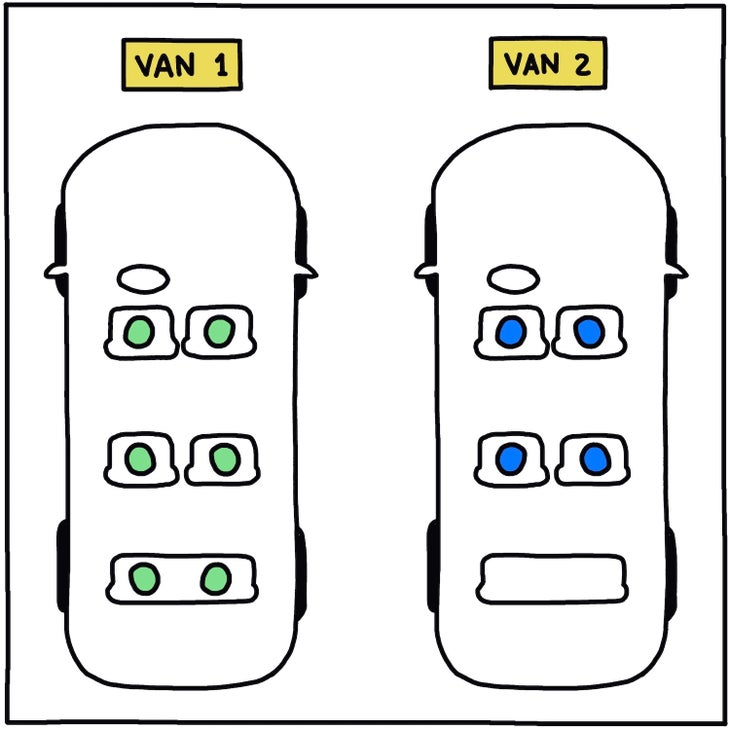

Josh has done听 Relay Iowa every year for more than a decade, and has developed a system that is kind of complex, but also genius. For the bulk of the weekend, the team splits into two groups: One van of six runners who are running, and the other van with four runners resting (or taking showers, eating gas station pizza, etc.).

Van No. 1, the one with six people in it, is further split into two groups of three people. Three runners who rotate through the front seat of the van, alternating driving and running, and three runners who are sitting in the back eating snacks, cracking jokes, napping, and/or reading Internets on their phones.

What I think is the smartest thing about this system: When you鈥檙e tired, like I鈥檝e-had-three-hours-of-sleep-in-the-past-40-hours tired, you still have to drive. BUT: You鈥檝e just run a mile before you jump behind the wheel, so your heart rate is still quite high, and you don鈥檛 have to chug Monster energy drinks or whatever to stay awake behind the wheel. Also, you鈥檙e only driving one mile at a time. Slowly. On pretty empty roads.

My second Relay mile was a straight line down the same road, and the third mile was almost all downhill, losing 150 feet of elevation in a mile, so I thought I鈥檇 just run fast for fun. It ended up being my fastest ever mile on Strava (which was unfortunate, because now I鈥檒l never break my record). I turned left onto the highway into the town of Anthon, saw Greg waiting on the shoulder, handed him the baton, and jogged over to our van, waiting at a gas pump at the Cenex station. Parker walked out of the convenience store and hopped into the back seat of the van carrying a cardboard boat of mozzarella sticks. Anthon, coincidentally, , the world record holder for the longest continuous attack of hiccups, from 1922 to 1990.

We passed the baton between runners for a while, which was kind of fun, since I haven鈥檛 run with a baton since my last high school track season, but also kind of gross when you鈥檙e handing it between ten people who are essentially living out of vans for two and a half days and who have limited handwashing opportunities.

When the baton got to Steve, he said something like, 鈥淚鈥檓 not running with a fucking baton,鈥� and that was that for a while. We bumped fists or high-fived when switching runners, and that worked just as well (and might be more sanitary). The baton popped back in for a few hours, some runners using it for a while, and then somebody left it in the van, and it just kind of rolled around the back seats for the rest of the trip.

There鈥檚 no requirement for teams to carry a baton鈥擩osh just thought it would be fun. The relay organizers have given each team a tracking device to carry, but we鈥檙e not required to carry it in our hands when we鈥檙e actually running. It鈥檚 more for them to keep track of where we are, and for the tracking website, in case any of our friends and family are keeping tabs on us from home. We keep ours in the van, so it鈥檚 always one mile or less from our actual runner.

There are relay rules, of course, but it鈥檚 not a race, so you can鈥檛 really 鈥渃heat.鈥� If your team is struggling and falling behind significantly, the relay allows something called 鈥渄ouble running,鈥� in which, say, Steve and I would run five miles together, totaling 10 miles, and then we could both hop in the van and ride ahead five miles, in order to gain some time. We don鈥檛 end up needing to do this at all, and just keep running, one person at a time, mostly one mile at a time.

My fifth mile of running, Mile 36 of the Relay, ended just as the course switched to gravel roads for a few miles. My sixth mile was also on gravel, and Josh says I was lucky it was overcast, as the gravel is usually way hotter than the asphalt when it鈥檚 sunny outside.

My Mile 7 (Mile 41) started on a Level B dirt road, which in Iowa means it鈥檚 not maintained, and is probably too rough for a rented Dodge Caravan. So I got to run two miles, to the next spot the van could meet me. The road is essentially a two-track dirt road between farm fields, a straight shot west to east, but it鈥檚 bermed in spots and trees crop up on each side from time to time, a little respite of wild in a landscape almost completely tamed by agriculture in all directions to the horizons. Two miles felt surprisingly long (I haven鈥檛 run this far at one shot since Tuesday!), and I hopped back in the van, sweaty, for a five-hour break while another crew of our guys took on the next chunk of 30 miles.

We stopped for a spaghetti dinner at the elementary school in Ida Grove (pop. 2,051, aka 鈥淐astletown USA鈥� due to the many built by farm and marine equipment magnate Byron Godbersen in the 1970s and 80s. For ten minutes, we sat at cafeteria tables in the school hallway to efficiently take down some pasta prepared by lovely volunteers, before heading back out onto the road. We continued progressing at approximately 6.5 mph across the state of Iowa in the late-afternoon sun, one guy running, handing off to another guy, some other guys watching from the van, which moved down the road every seven or eight minutes as necessary. It went on like this for some time.

Is it boring? Yeah, I mean, sitting in a van, looking at corn and soybean fields, nowhere to go, it is a little boring. But so is mountaineering, slogging up a steep snow slope in crampons. I guess the view is better, according to most people. But no gas station pizza on the side of Mt. Rainier, unless you bring your own, in which case it wouldn鈥檛 be as fresh.

Mitch and Greg and I rotated through miles 76 to 96, the sun setting in the middle of our leg. We put on reflective vests and headlamps so cars could see us on the left-hand side of the road, but when I ran and heard a car approaching, I jumped onto the gravel shoulder just in case. The front passenger seat of the van had become saturated with a cocktail of six different people鈥檚 sweat, which is just the way it is here when temps are in the 70s and 80s and humidity is, well, I guess it鈥檚 not the heat, it鈥檚 the humidity.

I got the last one-mile leg into Lake City, ending literally in the parking lot of a Casey鈥檚 convenience store, the Iowa-born chain that is a) the fifth-largest pizza retailer in the United States and b) closed, as of four minutes before I shuffled into the parking lot, in case I wanted to eat a pizza at the end of my running shift. Which I did, but it was not an option.

We met our other van and the rest of the guys at the Lake City town square, where they had sprawled out in the grass for the past few hours trying to sleep amongst a few dozen other Relay team members, as Friday night traffic鈥攋ust one guy on his loud motorcycle doing laps鈥攃ontinued on as usual.

We shuffled people and gear in and out of vans, and even though it was almost summer in Iowa, I realized I should have asked a couple more questions before packing for this trip, namely: 鈥渟hould I bring a sleeping bag?鈥�

I put on every article of clothing I had with me, which included many thin, breathable running layers, but no pants. I shoved my legs into my empty backpack, and tried to get comfortable under the glow of streetlights, the occasional vroom of Motorcycle Guy or someone else, and the headlights of other Relay support vehicles pulling in and out of parking spots at the perimeter of the park. I think I caught maybe two 30-minute naps. And then my alarm went off at 2:30 A.M. and we were due to meet the rest of the team down the road about 30 miles, at about mile 131.

I volunteered to drive, and from behind the wheel, moving along at 55 mph in the dark, the spectacle of the whole thing crystallized for me: the long blinks of the red lights on the army of wind turbines spreading across the horizon, slowly getting closer as we rolled through the blackness; the reflective vest and red light of a runner shuffling along the left side of the highway, then a minute or two later the flashing hazard lights of a vehicle pulled over on the shoulder waiting for the runner, then another runner, another vehicle, a group of vehicles, another runner, another runner鈥攁ll these weird people forming a loose caravan along a county highway that would otherwise be almost empty at this hour of a weekend morning.

I started my next shift at 3:50 A.M., a slightly downhill mile in the dark, then handed off to Josh, who handed off to Andy, who handed back to me, repeat, repeat, repeat, and the sun started coming up slowly, and I finished my shift at 5:27 A.M. A few hours later, we pulled into the town of Jewell, where a church had a pancake breakfast, which I partook in, and the high school had showers, which I did not partake in, and we rolled on. I had a seven-hour break between running, and I tried to sleep a little bit at a park in Eldora, but had no luck.

As we passed the halfway mark of the 339-mile relay course, I started to feel that in ultramarathon terms, the experience was half that of a runner and half crew member. As a member of our team, I ran about one-tenth of the miles, which means I spent about five and a half hours running, and about 47 hours waiting, driving, eating pancakes, pooping in the roadside ditch when it was our only option, retrieving complimentary single-serving ice creams for the entire team at Hansen Dairy in Hudson, and telling the story of how my friend Tony鈥檚 dad, Randy, punched our other friend, Nick, in the face, knocking him and his beer out of a lawn chair, when they were full-grown men riding RAGBRAI together for the second or third time, an event I did not see firsthand, but heard about later, and only thought of as a few of us on the Relay Team were splitting a Casey鈥檚 pizza in the parking lot of Independence High School, which was where Nick played basketball in high school and was quite good if I remember correctly. (Nick was just fine after the punch, if a little surprised, and I bet with a couple decades of retrospect, would probably say he might have had that one coming after all)

I slept a little bit in the Independence High School wrestling room, maybe an hour and a half, and ran my next shift of 4.3 miles with Mitch and Brian P. in the dark, starting around 2 A.M. and finishing just before 4:00 A.M., running downhill on the sidewalk into the deserted streets of Manchester.

I drank a can of warm iced coffee during my break, watched the sun come up from the back seats of the van, and then ran a couple miles leaving the town of Dyersville. If you鈥檝e heard of any place in Iowa, you may have heard of the Field of Dreams, an actual baseball field constructed near Dyersville for the making of the 1989 Kevin Costner movie Field of Dreams (and as of a few years ago, home to an additional, functioning baseball stadium next door, where my dad likes to tell people, the New York Yankees in 2021 became the only team to lose a Major League Baseball game in Iowa, to the Chicago White Sox, in the MLB at Field of Dreams game).

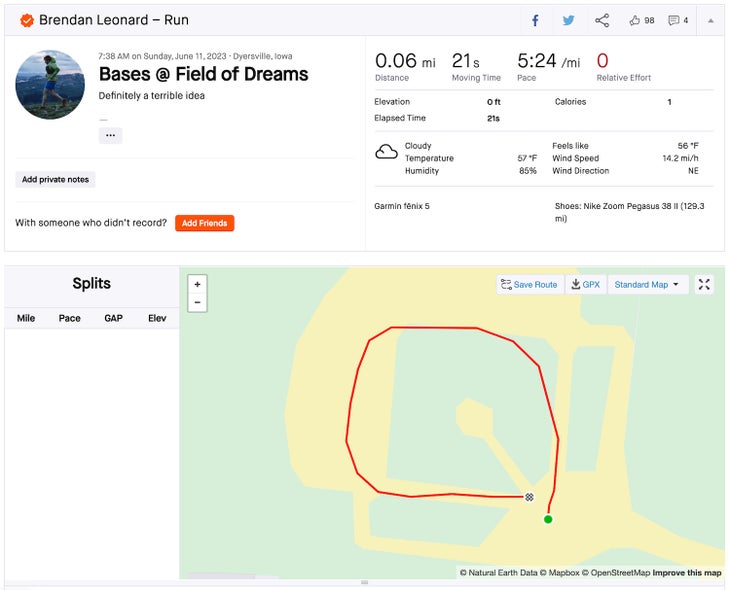

The Field of Dreams is, of course, on the relay route (mile 304), and Josh, Andy, and I ran the bases. I was disappointed to learn that the route around the bases at the Field of Dreams, of course only being 360 feet, is much too short to be a Strava segment. .

As we rolled into the outskirts of Dubuque, we started to split our legs into smaller segments鈥攁 half-mile each instead of one mile. So both vans traveled together, and we shuffled our five-minute chunks. Then we stopped and parked the vans in a lot just outside A.Y. McDonald Park on the Mississippi River, put on matching ugly-ass tank tops (singlets?) Josh and Andy had bought for the team, and jogged to the finish line together. And then it was over.

I wasn鈥檛 looking for a transformative experience, or some allegorical story about coming back to where I grew up and having an epiphany. I just thought it sounded fun, and it was fun. I got to do it with nine guys who were friendly, funny, interesting, came to run 339 miles together without complaining or much sleep, really, and they let me tag along.

I ran 34 segments total, each one of them a separate experience, but knowing how memory fades, I won鈥檛 remember all of them, or even most of them. But I think I鈥檒l remember the feeling of running down a county highway in the middle of the night, headlamp illuminating the ten feet in front of me, my shoes slapping the wet asphalt next to the white paint, only hearing my own breathing for eight minutes, until I catch up to the van, fist-bump Mitch, hop into the driver鈥檚 seat and put the van in gear, as I wonder where Brian P. found these club mashups that are blasting over the speakers as Drew, Brian B., and Parker sleep in the back seats. I mean, what a fucking weird way to spend a weekend.

The post Running 339 Miles Through Rural Iowa Is More Fun than You’d Expect appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

In his new book 鈥楾he Swine Republic,鈥� environmental scientist Chris Jones tells hard truths about Iowa鈥檚 agricultural industry and how its farming practices contaminate water thousands of miles away

The post Hog Poop from Iowa Is Polluting Your Water appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

To mark the unofficial start of summer over Memorial Day weekend, my partner and I went hiking at Geode State Park near our home in rural southeast Iowa. As we walked around the lake, we came across two towheaded boys no older than ten. 鈥淢y brother keeps losing his lure,鈥� the older one told us, shaking his head, as the younger boy waded knee-deep into the water. On the grass behind them lay an open fishing tackle box, as well as two iPhones鈥攖hose necessary evils for today鈥檚 unsupervised children鈥攖hat appeared to have been mindlessly tossed aside. For anyone worried about kids wasting their lives in front of screens, this would be a heartening sight. But as we made our way around the lake, we noticed patches of toxic blue-green algae blooming on the water鈥檚 surface.

As the nation鈥檚 top pork producer, outnumber its three million people by more than seven-to-one. Every year, millions of pounds of raw hog waste are applied to the state鈥檚 corn and soybean fields. Nutrients from fertilizer wash into lakes and streams, poisoning water that flows into the Missouri and Mississippi river basins, which provide drinking water to a combined 28 million Americans. The state鈥檚 tributaries to the Mississippi have played an outsized role in creating 听an oxygen-depleted area of the ocean.

Iowa鈥檚 answer to this colossal problem is its nutrient reduction strategy, a $5 billion effort which, since 2013, has encouraged farmers to voluntarily adopt more sustainable practices. According to environmental scientist Chris Jones, it hasn鈥檛 worked. For eight years, Jones sounded the alarm on Iowa鈥檚 worsening water quality as a research engineer at the University of Iowa. In blog posts published on the school鈥檚 website, he wrote provocatively about the agricultural lobby鈥檚 castigating industry and political leaders for .

His outspokenness has made him a thorn in the side of agribusiness and its beneficiaries. , he calculated that manure from Iowa鈥檚 livestock and poultry generates the human waste equivalent of a whopping 168 million people. The Iowa Farm Bureau fired back criticizing Jones鈥� 鈥減oop blog.鈥� In 2021, when Jones pointed out the plain fact that poor people and people of color are more likely to have their drinking water , a state representative accused him of

Jones decided to retire this spring, after he says state senators Tom Shipley and Dan Zumbach approached a university lobbyist with printouts of his blog posts, insinuating that school funding would be cut if the blog was allowed to continue. Shipley told 国产吃瓜黑料 the allegation was 鈥渁bsolutely false.鈥� Zumbach could not be reached for comment, but he in May that Jones鈥� claim is 鈥渞eckless and potentially defamatory.鈥�

Also last month, the Iowa House passed a bill that would eliminate funding for the state鈥檚 network of , a project once managed by Jones that provides Iowans with real-time data on dozens of lakes and streams. 听

To say the least, the future of Iowa鈥檚 waterways looks bleak. But as Jones writes in his new book, , remaining hopeful is a moral imperative. The book includes听a collection of essays from Jones鈥� blog, as well as some new material. I spoke with Jones about the forces driving Iowa鈥檚 water crisis, and what everyday people can do to improve water quality in their own communities.

OUTSIDE: There鈥檚 a common expression that manure is 鈥渢he smell of money.鈥� In some circles, it feels like the only socially acceptable way you can acknowledge the stench. The idea is if you complain, you鈥檙e disrespecting farmers. How does this attitude keep us from having tough conversations about the agricultural industry?

That saying goes way back. But manure doesn鈥檛 quite smell the way it used to, since we have such a large number of hogs concentrated in small areas. We used to have 60,000 farmers in Iowa raising hogs, and now we鈥檙e down to maybe 5,000 or so. I don鈥檛 think people give that saying as much consideration as they used to.

We treat farmers like royalty here鈥攁t least, some of us do. When politicians film TV commercials in Iowa, they want to go out and stand on a farm. And so, we鈥檙e willing to cut farmers some slack on the environmental consequences of their work. That is certainly an obstacle to solving our pollution problem. Now, I鈥檓 not saying farmers are bad. They鈥檙e human beings. Like the rest of us, they make decisions in their own self-interest. If we want to improve the conditions here, we need to change the framework in which they make their decisions.

Earlier this year, the state released revealing that Iowa has the second-highest cancer rate in the country (behind Kentucky), and is the only state with a rising rate of cancer. Nitrate in drinking water can increase the risks of colon, kidney, and stomach cancers, but the word 鈥渘itrate鈥� is nowhere to be found in the report. What鈥檚 your assessment of how the state has addressed water quality as a public health issue?

When the Safe Drinking Water Act was passed in 1974, the maximum contaminant level for nitrate was set at ten milligrams per liter, or ten parts per million. That was intended to protect infants, who developed blue baby syndrome after drinking formula prepared with nitrate-laden well water. Now, we know that drinking water with high levels of nitrate , even at levels below the U.S. legal standard. It鈥檚 not too difficult to believe that nitrate in our drinking water is driving higher cancer rates. Many people across Iowa never drink water with nitrate levels below five parts per million, and that鈥檚 considerably above the levels associated with increased cancer risk in the recent literature. Our state agencies aren鈥檛 talking about the dangers of consuming nitrate at lower levels.

One of your essays is titled, 鈥淢iddle of Nowhere Is Downstream from Somewhere.鈥� The essay is about hog waste in the Iowa River. But it reminded me of how water pollution in this state doesn鈥檛 only affect Iowans. Can you explain how our agricultural practices impact people and wildlife beyond Iowa?

We鈥檙e polluting water at a continental scale. Iowa occupies 4.5 percent of land area in the Mississippi Basin, but contributes to 29 percent of the nitrate and 15 percent of the phosphorus polluting the Gulf of Mexico. What we do here is impacting water quality 1,500 miles away.

The dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico is created by algae blooms, which thrive on high-nutrient water. When the algae dies, it sucks oxygen out of the water and kills off fish, shrimp, and other desirable species. The algae also produces toxins that are harmful to your liver and neural system. Those toxins can be very difficult to remove during the water treatment process, so people end up drinking them.

We鈥檙e polluting water at a continental scale.

One-fifth of Iowa鈥檚 land area is used to grow corn for fuel ethanol, and more than half of our corn is used for this purpose. How is ethanol production connected to Iowa鈥檚 poor water quality?听

Corn is one of the most environmentally intensive crops you can grow. It requires a large amount of chemicals and fertilizer, as well as diesel fuel to plant and harvest it. Many farmers also believe corn requires aggressive tillage, so we have soil erosion associated with that which leads to water pollution. The conventional wisdom is that ethanol fuel produces less carbon emissions than regular petroleum. But recent research shows that鈥檚 not true. found that greenhouse gas emissions increased 24 percent with ethanol versus gasoline.

There are crops we could grow on those acres that would produce better environmental outcomes. Iowa used to be the biggest apple producer in the country. We also used to be the nation鈥檚 leading oats producer. Now, we hardly grow anything except corn and soybeans.

All of the infrastructure we have here is aligned with those crops. And that includes the transportation system, the crop insurance industry, the fertilizer manufacturers, and all the agricultural retailers across Iowa鈥攖here are 1,100 of them. If we’re going to do something different, we need market development and policies that would enable that transition.

Last summer, had advisories against swimming due to high levels of bacteria or toxins. As climate change causes temperatures to soar, access to water recreation is increasingly important. What are your thoughts on that?

This is a quality of life issue. Iowa has three million people, and we鈥檝e had around three million people for decades. If we want people to move here, and if we want to retain young people, we need clean water and places where you can enjoy the outdoors. You鈥檙e not going to select Iowa on that basis if you have other choices on where to live.

Iowa鈥檚 percentage of public land (2.8 percent) ranks 48th in the country, only beating Kansas, another agricultural state, and Rhode Island. Only seven percent of that land is within state park boundaries. How does this lack of green space connect to our water quality issues? 听

Only about one percent of the state鈥檚 land area is really usable from a recreational standpoint. Natural areas tend to buffer what鈥檚 happening on working lands by reducing flooding and storing carbon. Minnesota is a farming state, but there鈥檚 also a lot of parks, which mitigates the environmental consequences of agriculture. Here, we don鈥檛 have that. Everything that can be farmed in Iowa is farmed.

Water in nature shouldn鈥檛 smell. I鈥檓 standing in front of a river right now, and it smells.

When you鈥檝e talked with other Iowans about our lack of outdoor recreation space, is that something that people are aware of? I feel like if you grew up here, you don鈥檛 really know anything else.

I think that鈥檚 right. Iowans have vacationed to Minnesota and Wisconsin for generations. We could have those types of experiences here鈥攆ishing, paddling, canoeing. We could have some really remarkable rivers if we wanted to. But I think people are accustomed to the current condition. There鈥檚 fatigue on this. They see that it isn鈥檛 changing, and so they鈥檒l just spend the extra money to drive 500 miles to do what they want to do. Do we really want to be known as a state where you can鈥檛 do much in the outdoors?

You write about a number of policy changes that you believe would improve Iowa鈥檚 water quality鈥攂anning the application of manure to frozen ground, limiting livestock鈥檚 access to streams, and diversifying farm operations, to name a few. But there鈥檚 very little political will at the state level to take action. What can ordinary Iowans do to enact change?

Just because the legislature doesn鈥檛 want to do these things, doesn鈥檛 mean we shouldn鈥檛 talk about them. The fact that we have a state where agriculture dominates 85 percent of our land area and it basically goes unregulated鈥攖hat鈥檚 got to be a discussion topic. To eventually make these taboo solutions acceptable, you need to talk about these things. It鈥檚 not that regulation won鈥檛 work. They鈥檙e afraid that if we had regulations, they would work, and people would want more.

If people want change, it鈥檚 got to happen at the grassroots level. You have to engage your local officials. That鈥檚 how I see change happening. I don鈥檛 see it happening from above.

Go out and look at a lake or stream by your house. Does it look the way you think it should look? And does it smell the way you think it should smell? Water in nature shouldn鈥檛 smell. I鈥檓 standing in front of a river right now, and it smells. I always tell people, 鈥榊ou don鈥檛 need to believe me. Just go out and look for yourself.鈥�

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The post Hog Poop from Iowa Is Polluting Your Water appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

After a year spent inside with too much time on his hands, a writer survives two days in the woods with only the equipment available to his hobbit alter ego鈥攔apier and lute included

The post I Went Camping as My Dungeons & Dragons Character appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

Prologue

When I heard the snap of branches coming from the darkness surrounding our camp, my hand tightened around the hilt of my sword. My eyes scanned for the source of the noise听but saw nothing.

Could it have been a bear? Or even a troll looking for a meal? I prayed it was听not a band of cutthroat goblins seeking to plunder our hard-earned treasures.

That鈥檚 when I spotted it: a wolflike creature stalking toward听me in darkness. I turned to Tanner the ranger, my traveling companion, to warn him. But I discovered to my horror that a large dark shadow had appeared right next to him. Before I could draw my sword, the wolf creature was already upon me. It was too late.

Chapter 1: The Beginning听

I love Dungeons & Dragons鈥攑robably too much.

When the pandemic started, I, along with millions of others, turned to D&D for fun and socializing. After all, the real world really sucks right now. Some people escape by learning a new language or reading. We escape by pretending to be elves. Don鈥檛 judge.

Over the past year,听many of the physical activities I used to do, like going to the gym, fell by the wayside. It鈥檚 had an acute impact on my physical and mental well-being鈥攁nd . Even as we emerge from the worst of the pandemic,听social isolation has听created a lasting crisis of anxiety, stress, and depression for many across the world.

These thoughts culminated one day while I was huffing home with a backpack filled with groceries, when I听wondered, How the hell does my D&D character carry their things while slaying orcs and exploring dungeons?

With more time on my hands than I knew what to do with, I figured now was the perfect opportunity听to answer that question.

My quest was simple: I鈥檇 go hiking and camping for two days carrying all the equipment my character carries. It would give me the chance to marry my love for D&D with my old love of doing听anything physical鈥�an听improvement over my current exercise of听only听getting up from my couch to grab听another beer from the fridge.

Of course, every adventure needs an adventuring party,听so听I recruited my college buddy Tanner. He鈥檚 an outdoorsman of the highest caliber, having hiked everywhere from the treacherous trails of eastern Iowa to the exotic locales of central Iowa.

I sent him a missive, imploring him to brave this perilous journey with me.听鈥淲anna go camping with me in a month?鈥� I texted. Not long after, he responded,听鈥淵eah, sure.鈥�

Now听I was ready to answer a question that philosophers, artists, poets, and scholars have ruminated on since time immemorial: What happens when a somewhat-out-of-shape writer tries to survive听in the wilderness using only the gear听available to his D&D character?

I was about to find out鈥攐r die trying.

Chapter 2: The Preparation

My character is Zaddy D. Vito,听halfling听bard and adventurer extraordinaire.

He and I are a little different. For one, I am a six-foot-one-inch human man, not a portly hobbit the size of . But Zaddy has panache and always makes things work with his cleverness鈥攕o I would, too.

In his听Explorer鈥檚 Pack, according to听the D&D player鈥檚 manual,听Zaddy carries听the following:

- A backpack

- A bedroll

- A mess kit

- A tinderbox

- Ten torches

- Ten days鈥� worth of rations

- A waterskin

- 50 feet of hempen rope

I already had some of these things: a听backpack, a bedroll, and a wineskin I got听as a souvenir from a trip to Spain. Through the magic of fate (read: Facebook Marketplace), I acquired a Boy Scouts mess kit, a survival tinderbox, and 50 feet of cotton rope. I also created ten听torches by combining free paint stirrers from Home Depot with a few ripped-up T-shirts.

That left rations, which the player鈥檚 manual says 鈥渃onsist of dry foods suitable for extended travel, including jerky, dried fruit, hardtack, and nuts.鈥� After a bafflingly expensive trip to the grocery store, I had听everything but the hardtack (a simple dry bread that sailors used to carry on long voyages), which I ended up baking on my own. True to its name, the batch I made was virtually inedible and could have doubled听as sidewalk chalk. I plan on sending future samples to NASA in case they want to use it to line space shuttles.

Zaddy also carries a rapier and a lute. My substitutes:听a fake sword from Craigslist and my girlfriend鈥檚 ukulele. All told, the equipment weighed just 25 pounds鈥攁 far cry from the 59 pounds that the player鈥檚 manual estimates he totes. I wasn鈥檛 about to complain,听though. With my setup听mustered, it was time to set off on my quest.

Chapter 3: The Quest

Tanner and I decided to camp at Lake Macbride State Park, north of Iowa City, Iowa,听for our adventure. The player鈥檚 manual doesn鈥檛 mention a tent, so we needed to build shelter for the night. Luckily, Tanner took a survivalist camping class once. With his guidance, we created a somewhat structurally sound shelter out of branches and leaves.

As we worked, a ferocious-looking dog barked at us from a nearby campsite. Its owner eyed us suspiciously. I made a听mental note to keep my sword close.

Once finished, I donned my equipment and we set out. In D&D, players accept quests given by NPCs (non-playable characters). I figured we could do the same by soliciting quests from strangers in the park.

To our surprise, folks听didn鈥檛 immediately call the cops on us when we approached. In fact, we ended up completing quests and getting rewards like real D&D characters. Our quest-givers included:

- A group of students from the University of Iowa. Their quest: for us to drink a shooter of Fireball. Their reward: two hard seltzers.

- A lovely older couple traveling around the Midwest. Their quest: for me to play them a song on the ukulele. Their reward: a听handful of Dove dark chocolates.

- A young couple with excitable dogs. Their quest: for听me to play them a song on my ukulele (I was afraid everyone else would want this, too, but luckily they didn鈥檛). Their reward: a can of light beer.

For our last quest, we came upon a large family, whose dad told us, 鈥淔ind a morel mushroom. We鈥檙e making pizzas, so we can use it as a topping. We鈥檒l make you one, too… if you find it.鈥�

Tanner smiled. He was a mushroom-hunting veteran and knew exactly how to locate them. We took off into the woods, confident that we鈥檇 come across听a morel soon enough. Alas, after an hour, we were tired, hungry, and mushroom-less. Defeated, we headed back to the family to report our failure.

Yet won over by the sheer silliness of what we were doing, they decided to make us a pizza anyway. So we drank our beers and ate pizza while reflecting on a hard day of adventuring.

Darkness had fallen by the time we made it back to our campsite. I fumbled through my backpack, looking for the tinderbox to light a fire. That鈥檚 when I heard the snapping of branches.

I looked up and noticed a dark shape walking toward me. In my mind, I saw a wolf ready to pounce. In a panic, I grabbed the hilt of my sword, ready to cut down my foe. But before I could do anything, it was already at my feet鈥� sniffing. It was the听dog from the camp nearby.

Relieved, I looked at Tanner to tell him about it鈥攁nd saw the silhouette of a man next to him. I could imagine听the headlines already: 鈥淢an with Sword and Inedible Bread Found Murdered.鈥�

鈥淵ou boys have any cigarettes?鈥� he asked. Tanner shook his head. I fished out a pack from my pocket and gave him one. The man lit it and stood there for a moment before walking away.

鈥淭hat was weird,鈥� Tanner said. We laughed. Soon after,听I found my tinderbox. Tanner made a small pile of leaves and twigs in the camp鈥檚 fire pit鈥攂ut I realized we had forgotten to grab firewood.

As I was about to search for听some, three logs fell on the ground next to me with a thud, as if gifted from the gods. I glanced听up and saw it was none other than the stranger who had bummed cigarettes from us.

鈥淭hought you boys could use some,鈥� he said before quickly disappearing into the darkness. Tanner and I exchanged looks.

Quest and reward鈥攋ust like D&D.

Chapter 4: The End

We decided to go hiking the next day, though we were both exhausted (surprisingly, our shelter was not the most comfortable place to sleep).

I could feel everyone鈥檚 eyes on me as we trekked听down the trail. To their credit, I don鈥檛 think any of them expected to see a man with a ukulele and a sword hiking alongside them that Sunday.

The hike was a lot tougher than I anticipated. Though my pack was lighter than the one Zaddy uses, it felt like a hundred听pounds by the end. Eventually, we stopped near a lake, and I fell asleep as soon as I lay down.

After I awoke, we headed back to the campsite. Each step was harder than the last, and I took many opportunities to rest and 鈥渁dmire the scenery.鈥� If Tanner knew I was tired, he didn鈥檛 let on. He鈥檚 that kind of guy.

We made it back to the campsite in time for lunch, and attempted to eat a few bites of hardtack but gave up before we chipped a tooth.

By this point, I had a fairly good idea of what Zaddy endures, and I told Tanner that our quest was a success. He nodded and agreed. As is bro custom, before going our separate ways,听we made our requisite vague promises to hang out again.

As I cleaned up the campground, I reflected on what I鈥檇 learned. For one, I鈥檒l be sure to opt in for my workplace鈥檚 dental plan if I plan before听eating hardtack again. Also, hiking isn鈥檛 as fun when you鈥檙e carrying 25 pounds of equipment, a sword, and a ukulele.

But I also learned that even in the height of a pandemic, plenty of people听were still willing to lend a hand and share some pizza with complete strangers鈥攅ven two men armed with swords.

The biggest lesson for me, though, is that your adventures are only as good as your adventuring party. Fortunately, I had a great partner: Tanner the ranger, builder of shelters, veteran morel hunter, and good friend.

The post I Went Camping as My Dungeons & Dragons Character appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

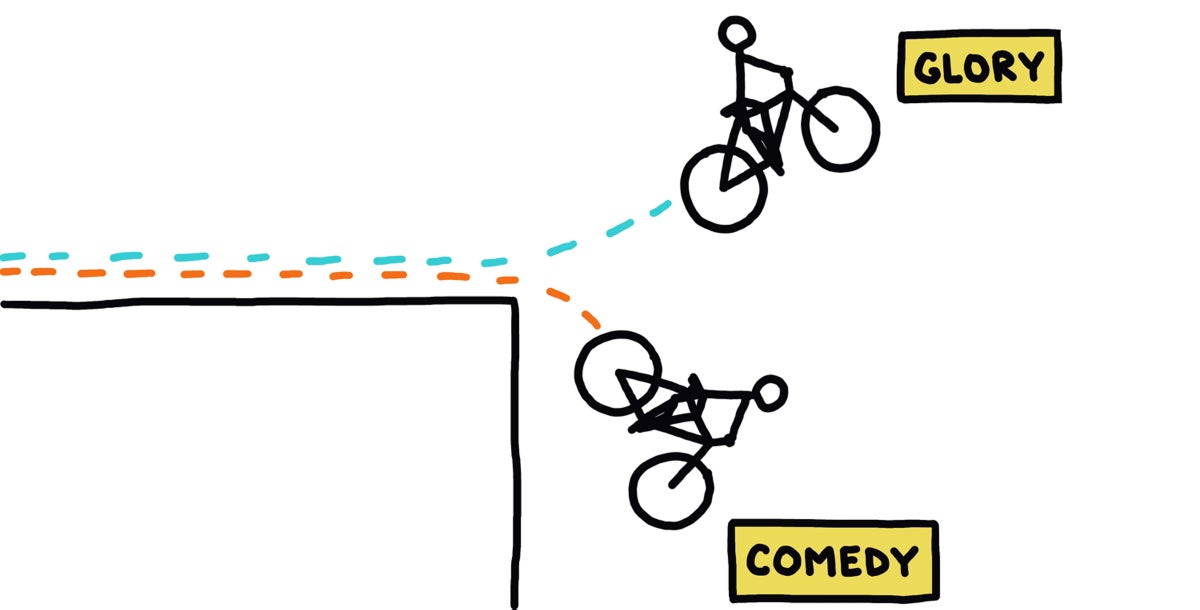

I didn't give up riding my bike off things that day in the driveway鈥擨 learned to ride wheelies, went off a few small trailside ski jumps, and, later, mountain-biked proficiently enough to enjoy both of my tires leaving the ground for up to three-quarters of a second at a time.

The post Smashing My Face into the Pavement Changed My Life appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

In my memories听of the听house,听the retaining wall is always around three feet high. But after three decades听and a little Googling, I now realize there鈥檚 no way it was taller than 21 inches. Still, when I was seven and a half years old, it was a big deal.

I had a black and gold Huffy Thunder 50 dirt bike听that, in retrospect, I realize听was a vehicle for many life lessons, not the least of which was learning how to get up a hill, courtesy of my mom, who would not let me stop pedaling and walk my bike up it on the way back to our house after Little League practice; instead,听we鈥檇 just ride circles around a flat spot until my legs stopped screaming, and then we鈥檇 finish pedaling up the last two blocks to the house. That was a noble lesson in persistence, which continued to pay dividends听in many areas of my life in the听decades afterward.

The other lesson learned on听my Thunder 50听was about physics. Mostly gravity. That听retaining wall along the driveway of our house鈥攖hree railroad ties stacked on top of each other鈥攌ept the neighbors鈥� front yard from rolling into our driveway, which was just wide enough for two cars. If you were playing basketball, the wall听was almost enough for a high school regulation three-point line: 19 feet听9 inches from the hoop, or just past the edge of the driveway and in the dirt of the front yard, under the branches of the big sugar maple tree. You could get off a shot without hitting the branches听if you stood right in front of where the three-point line would be.听

I had seen my brother Chad, who is a year and a half older than me and naturally more relaxed and athletic in every听sport听we tried as kids,听ride his BMX bike off the retaining wall with no hesitation or real effort, landing on both wheels in the driveway and then steering out to the right onto Cherry Street. I鈥檓 sure I assumed I would try it someday myself鈥攊t was just a matter of working up the nerve. I have since wondered why I chose the night before my first day of third grade, and I have听no explanation听other than kids who are seven are kind of dumb shits. (We continue to be dumb shits in many ways throughout life听but hopefully recognize this fact early on and spend significant effort trying to become less of a dumb shit every year we are alive.听Of course there are pivotal moments, and this was听one of mine.)

I pedaled around the driveway, then up the neighbors鈥� driveway, checking out the launch point but chickening out several times. I probably spent a few thousand hours in the driveway of that house, mostly playing basketball by myself, and听in my memory, the scene of this particular August day听is always lit with the golden light just before dusk, when I finally got together the nerve for my attempt. Nobody else was around, no friends peer-pressuring me into it, no one wanting me to hurry up so they could take a turn. It was just me, trying stuff by myself.

Biking through the grass and up to the top of the retaining wall, I听expected I would just float off as I had seen my brother do, landing on the pavement and rolling away, a small triumph. Instead: I didn鈥檛 pull up on the handlebars hard enough (or at all?), I might have been going too slowly, and I rolled off the retaining wall, plummeting听down onto听my front wheel, toppling over the handlebars, and catching most of the brunt of the fall with my face. It had less the grace of a bicycle stunt a third-grader imagines and听more the grace of a load of dirt sliding from the back of a dump truck as the driver tilts the bed up and back and the tailgate swings open.听

My family moved from that house in southwest Iowa across the state a few years later, so I haven鈥檛 been back to the scene of the crash since I was 13, but thanks to Google Street View, I can revisit it online and see where it happened. The house has been painted a different color, and听the basketball hoop has changed, but everything else looks the same.

And like a lot of things from my earlier years, including not getting sent to detention in high school (just keep your mouth shut about 75 percent more often) and dating (also keep your mouth shut about 75 percent more often), doing it better seems so simple in retrospect: pedal hard, pull up. As the saying goes: Good judgment comes from experience, and experience comes from poor judgment.

Of course, at the time, I didn鈥檛 pedal harder or pull up, so after I peeled myself and my bicycle off the pavement, I went into the house with blood starting to trickle down听my face and my upper lip starting to swell. The first day of school started in about 13 hours, and I don鈥檛 remember exactly what I wore听that next day, but when I was growing up, you wore nice clothes the first day of school, so I probably did, maybe even a new shirt. But also: two giant scabs on my face.

Eight years later, I went to high school on the opposite side of the state听and befriended a classmate named Dan, who had a smile that took up half his face. He loved to laugh, and so did I, but his laugh was so loud and bright that whenever I made him laugh in class, or in the hallway, or anywhere, I felt like I was doing everyone else a favor. And at some point, I told Dan the story of riding my bike off the edge of the retaining wall, landing on my face like a pile of dirt falling out of the back of a dump truck, and he听loved the story. Specifically when I remembered that there were two women walking down the street at the time, who had probably seen the whole thing from about 150 feet away, which struck Dan as probably the funniest part, and once he started laughing at it, I agreed with him. Dan probably made me retell him that story seven or eight times in high school, in the lunchroom, in the football locker room, in the back of someone鈥檚 car when we were drinking Busch Light driving down a gravel road somewhere in Chickasaw County.

When you鈥檙e really young, you get ideas from some rather ridiculous places about what you want to be when you grow up. You want to play in the NBA, be a rapper, or have a job that literally only exists in movies, like a hero cop who doesn鈥檛 play by the rules but always saves the day, or a writer who can afford to live in Manhattan. Lots of us, at one point or another, want to be good at flying off things on skateboards, skis, and/or bikes, and some people do become good at it and maybe make a living at it. I didn鈥檛 give up riding my bike off things that day in the driveway鈥擨 learned to ride wheelies, went off a few small trailside ski jumps, and听later听mountain biked proficiently enough to enjoy both of my tires leaving the ground for up to three-quarters of a second at a time. But I鈥檓 sure somewhere in my seven-and-a-half-year-old brain, I started to think maybe big air wasn鈥檛 going to be a thing for me.听

By the time I turned 25, I really wanted to be an adventure writer, following in the footsteps of climbing writers like Mark Jenkins, Jon Krakauer, and Daniel Duane. For a long time,听I felt like I should write stories about strong, courageous deeds, survival in near impossible situations, the sort of heroism we find in classic adventure tales. Thankfully, there鈥檚 room for other types of tales, not just the capital-A 国产吃瓜黑料 stuff I was first inspired by, and I鈥檝e听been able to make somewhat of a living from telling stories about the outdoors. Every once in a while, someone will ask me how I got started doing what I do, writing about the human-powered things we do for fun, and fun听in the mountains and on trails. Usually I tell them about the first mountain-climbing story I ever had published, for $40 back in 2004. But now that I think about it, that鈥檚 not true at all. It was probably dumping my bike off a knee-high jump in a driveway in a small town in southwest Iowa, landing on my face, and practicing telling and retelling that story to my giggling friend Dan, hoping to get it just right so everyone would hear him laughing three rows of lockers away.

Brendan Leonard鈥檚 new book, Bears Don鈥檛 Care About Your Problems: More Funny Shit in the Woods from听, is听.

The post Smashing My Face into the Pavement Changed My Life appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

I was an irresponsible person who was good at getting in trouble. I asked Dave for help, and he made a bet on me: his car. In order for him to keep his car, I had to change.

The post How to Show Up for Your Friends appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

I looked at the menu at a booth in Morg鈥檚, a diner in Waterloo, Iowa, on a cold morning in January, sure of one thing: the joke I was going to lob at my friend Dave near the end of breakfast. I was not sure the joke would actually be funny, but I was definitely going to say it.听

Dave and I get together almost every time I鈥檓 back in Iowa visiting my parents. He was my last roommate while living in the state, before I left to move west听in 2002, a shift of geography that rerouted my life completely. We鈥檝e stayed in touch since then, some years the thread of communication听thinner than others听but still there. Most of the time, when I come back, one or both of us has to drive more than an hour to make a meeting happen, just like this time.听

Dave walked in, sat down, and said, 鈥淚 think the last time we were here, I had just bailed you out of jail, a few blocks from here.鈥� I said I was 100 percent sure that was correct, and I don鈥檛 remember if I even ate anything that morning in March 2002听or just sat across from him and smoked Camel Lights, which you could do indoors in Iowa then. The night in jail followed what would be my last night ever drinking alcohol, which is a separate, long story. In my fuzzy memory, I鈥檇 called Dave from the jail phone听and told him I was stuck there until I could raise $3,000 in bail. I鈥檓 certain I called him instead of my parents because I had disappointed them enough over the past few years, and Dave would be less disappointed in me听but hopefully still understand.听

Dave showed up at a bail-bond place with the title to his car and $300 I might or might not be able to pay him back at the time, and I got to go home that morning instead of sitting in jail with a headache and the gut-punched feeling of what recovering addicts call rock bottom.听But first听we went to Morg鈥檚 for breakfast. Dave paid the bill, and before he headed to his shift waiting tables at a restaurant, he dropped me off back at the house we shared with our friend Nick. Over the next few months, and then years, my appreciation for what Dave did for me began to multiply.听

The simplest way to explain it is: at听that time in my life, I was an irresponsible person who was good at getting in trouble. I asked Dave for help, and he made a bet on me: his car. In order for him to keep his car, I had to change. Which was a big gamble at the time. As has since been pointed out to me, there鈥檚 a time and a place to cut someone off with tough love听instead of potentially enabling them to wreak further havoc. I don鈥檛 know exactly what Dave was thinking then, but I鈥檓 glad he bet on me that one last time.听

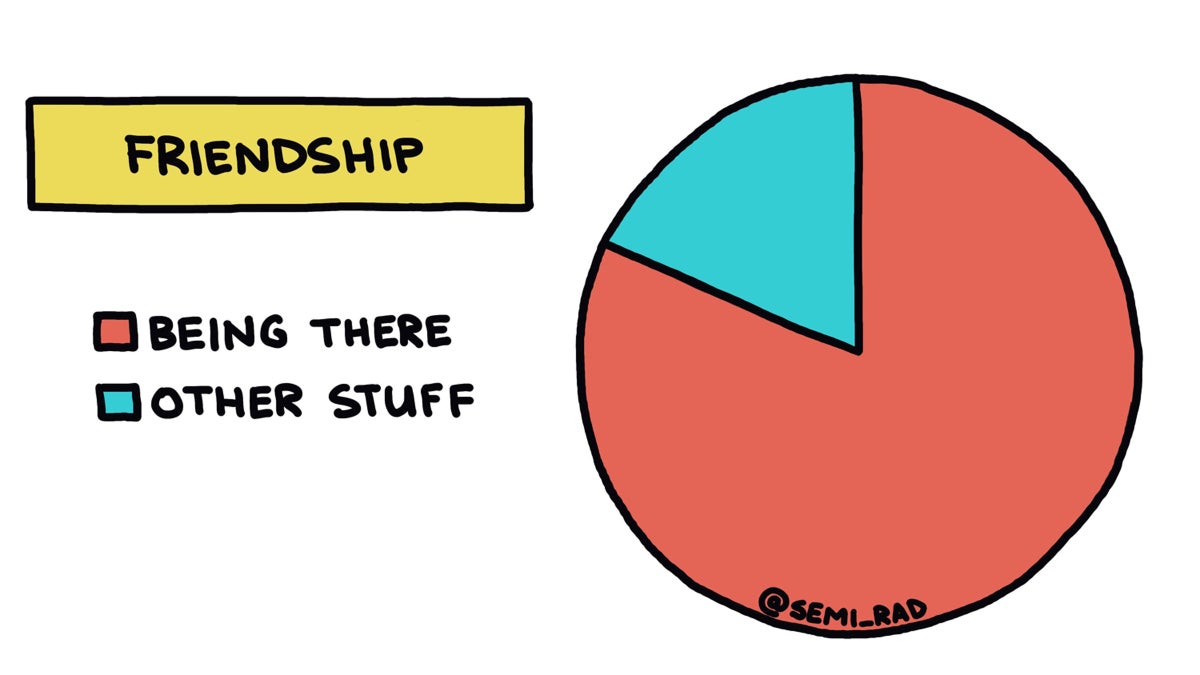

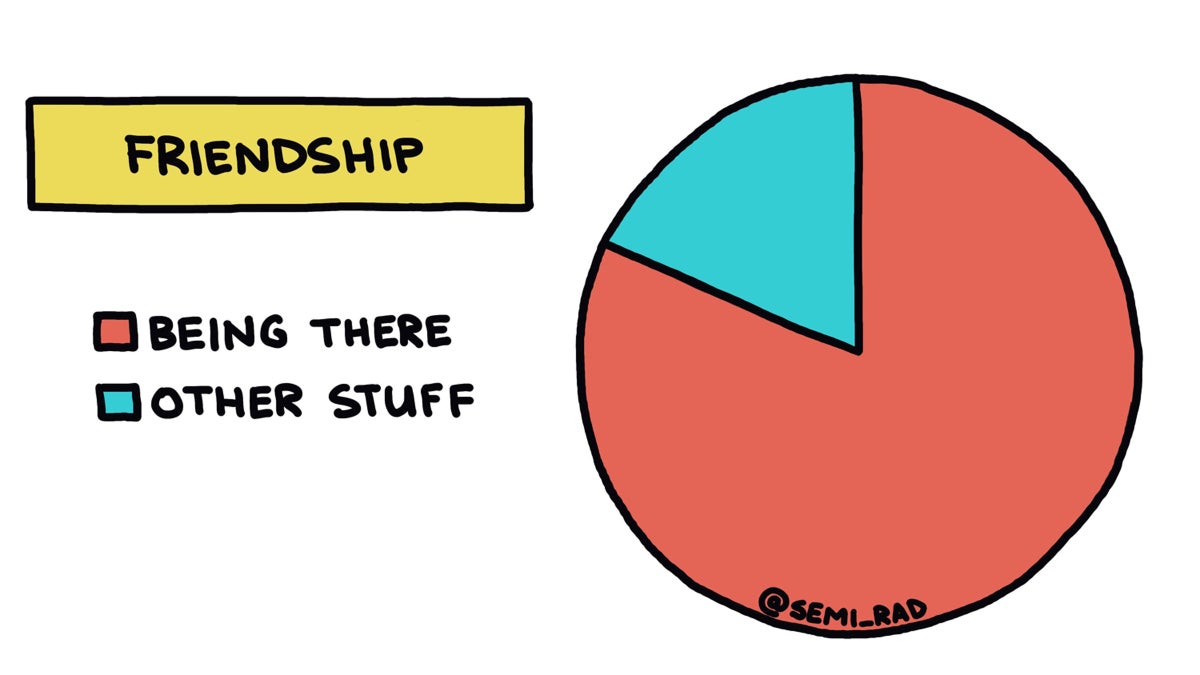

Over the years since, I started to see Dave鈥檚 gamble as a symbol, or more accurately, the defining act of what constitutes friendship: showing up. I would argue it鈥檚 the most important element of a friendship. If your friend needs a groomsman or a bridesmaid, help moving a couch, someone to talk to about something difficult they鈥檙e going through, a ride home from the airport, you show up for them.听

A few months after Dave bailed me out, I moved to Montana听and eventually Colorado. Every year听I tried to remember to text Dave and say, 鈥淭hanks for bailing me out in March 2002,鈥� just so he knew I never forgot it听and still appreciated it. The more I got into the mountains, the more I valued the people who showed up, whether it was on the belaying end of a climbing rope, a promise to switch their beacon to search mode and dig like a motherfucker in the event of an avalanche, or just arrive ready at the trailhead at the time we agreed upon, even if it was four听in the morning.听

Dave and I both eventually found our way to a common sport:听trail running. I casually mentioned getting together for听a week in Rocky Mountain National Park last听summer.听I was working on a guidebook and thought that听maybe he could come out for a few days and join me for some hiking and trail running. He decided to join me for ten days, and to my great joy, we got Dave up his first fourteener, Longs Peak, which is no walk in the park when you鈥檙e coming from the flatlands and you鈥檝e听spent almost zero time navigating talus and听scrambling听in thin air 13,500 feet higher than the house you live in.听

The more I got into the mountains, the more I valued the people who showed up.

When I was back in Iowa over the holidays, when Dave texted about getting together, I suggested Morg鈥檚. As we sat in the booth catching up, I tried to remember what it had looked like in 2002, the last time we were there together. I thought maybe it had been more dimly lit, but I wasn鈥檛 sure. I remembered the pancakes, which almost hung off the edges of large plates. The server dropped off the check, and I snatched it from the table before Dave could even get a finger on it. He made the face you make when your friend insists on buying breakfast, and then I said a line I had been thinking about for days, or maybe 17-plus years:

鈥淚鈥檒l get it. You got it last time.鈥澨�

We both laughed, more than was actually appropriate for the quality of the joke, and then I went on to say something like, 鈥淐ome on, you bailed me out of jail, risked losing your car, changed the course of my life, taught me one of the most important lessons about friendship, etc., etc., etc., so the least I can do is pay for your breakfast,鈥澨齱hich is, I believe, an advanced-level sarcastic-midwesterner way of saying to another midwesterner, genuinely but packaged inside a joke,听thanks for being there for me.

Brendan Leonard鈥檚 new book,听Bears Don鈥檛 Care About Your Problems: More Funny Shit in the Woods from , is听

The post How to Show Up for Your Friends appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

If you'd prefer to add some fly-fishing or paddling into your triathlon, opt for one of these unique events.

The post These Multisport Races Are Way More Fun than Triathlons appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

Let鈥檚 say you鈥檝e done the typical triathlon鈥攕wim, bike, run鈥攁nd now you鈥檙e looking for something different: a high-endurance race that crosses diverse听terrain听or a less rigorous event in which you can include family and friends of different skill levels. Or maybe you want to try听a multisport event, but the thought of听swimming in open water is more of a challenge than you鈥檇 like. Across the country, organizers have taken note, creating annual events听that combine all of a locale鈥檚 adventure offerings into one race. We鈥檝e rounded up some of our favorites (many of which don鈥檛 require donning a Speedo), and some are right around the corner this fall, so you can still sign up.

Cumberland, British Columbia

Mind Over Mountain 国产吃瓜黑料 Race

The听, which happens every听September in the historic mining town of Cumberland, on听Vancouver Island, combines endurance sports with navigation skills. Known for its world-class singletrack trails, the contest听centers on mountain biking听but also includes kayaking, hiking through the wilderness, and finding checkpoints听using a map. Compete听solo or join a team听of two or four people, pick between听a 30K sport course or a 50K enduro course, and be sure to spend the night at Mount听Washington Alpine Resort (from $50)鈥攊ts听postrace party is a good time. Interested in fine-tuning your map and compass skills?听The event鈥檚 organizers听offer听navigation clinics prior to race day.

Raton, New Mexico

Master of the Mountains

In early听September, racers at congregate at the starting line in northeastern听New Mexico鈥檚 Sugarite Canyon State Park, a three-hour drive from Albuquerque. From there it鈥檚 a six-mile trail run around Little Horse Mesa, a three-mile paddle across Lake Maloya in kayaks, a 22-mile bike ride on dirt and pavement, and a final shooting course at Raton Trap Club. (Make sure you know how to use a shotgun first.)听Do it on your own or as part of a two-to-four-person relay team.

Iowa and Colorado

Running Rivers Flyathlon