Black yoga teachers are creating communities. Just not where you'd expect.

The post Where Are the Black Yoga Studio Owners? appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

It鈥檚 been several years since South Asian yoga practitioners opened a dialogue around what has become the status quo in yoga鈥攊ts lack of color.

Although the numbers of those from traditionally marginalized communities who practice and teach yoga have been increasing, there remains considerable underrepresentation, particularly in the Black community.

According to Yoga Alliance鈥檚 recent published in November, Black teachers and studio owners make up a fraction of a fraction of the yoga space.聽 Although the number of yoga studios owned by Black yoga teachers has been on the rise, we鈥檙e still far more underrepresented than makes sense proportionate to the larger population.

As the founder and owner of a yoga studio and a Black woman, I ask, 鈥淏lack folks, why aren鈥檛 we owning more yoga studios?鈥�

After speaking with a number of Black teachers, the answer appears to be, 鈥淏ecause we don鈥檛 want to.鈥�

A Community-Centered Model

I founded in 2020 in the Houston Southside, a traditionally Black part of the city, to give displaced yogis a temporary home. I can attest to the difficulties of trying to operate a business in an increasingly crowded yoga space. Little by little, students and trainees who had never missed a class when I was teaching in an affluent part of town became less willing to make the trek to the new space. Far removed from where other yoga studios were located, my studio was failing because I was drawing on my former yoga community when I really needed to be focusing on the people right in my neighborhood.

Accessible yoga is about location, motivation, and connection as much as it is about adaptive shapes, tiered pricing, and inclusive spaces, suggests , psychologist, certified yoga therapist, , and President of the Black Yoga Teachers鈥� Alliance Board of Directors from 2020 through 2023. 鈥淲e can teach wherever we are,鈥� she says. Dr. Parker finds that many Black yoga teachers create yoga spaces within their neighborhoods鈥攃hurches, community centers, beauty salons, homes, online, and other collective spaces that don鈥檛 require that people travel outside their communities to practice.

Offering yoga in these 鈥渘ontraditional鈥� spaces can actually be considered more traditional than studios, according to the indigenous South Asian framework of yoga, where the practice has historically been shared in cultural centers, schools, ashrams, and other places where community is centered.

Reggie Hubbard, founder of Maryland-based , offers a mixture of online and in-person yoga practice, meditation, breathwork, sound, and wisdom in service to collective well-being. Although some of his in-person offerings take place in a studio, his aspirations don鈥檛 include owning a traditional space.

鈥淚 may open a studio in the model of a retreat center that teaches embodied practice or activist training,鈥� says Hubbard, who is a presenter at Kripalu, Sedona Yoga Festival, and BhaktiFest. 鈥淏ut I鈥檒l likely never own a traditional studio because it would take me away from my mission of taking yoga and peace practices to non-traditional communities primarily.鈥�

Community Can Be Different Than Inclusivity

Inclusion is not the same as feeling that you belong. Teaching through the lens of community repair requires operating very differently.

Studios and spaces owned and/or operated by Black teachers often focus on advocacy, community events, and rest. , the virtual studio I founded in 2021, was largely run by a small group of dedicated volunteers with all funds directed to the teachers. It has now transitioned into a yoga collective in which the teachers manage and run the offerings on a donation or sliding-scale basis while equitably profit sharing. Operating in this way has nurtured a community that is looking for people who think like them, look like them, and care about what is important to them.

Oya Heart Warrior, creator of U.K.-based , argues for the importance of a practice that celebrates our bodies and wanting to be together. 鈥淏lack people are often repelled by a yoga that tries to bend us into performative poses wearing tight, expensive, clothing,鈥� she says. In contrast, Warrior describes聽 her offerings as 鈥渁 tender practice of moving meditation and collective rest, to mobilize our joy and metabolize our pain, without a mat or linear movement.鈥�

As Black yogis search for community online, it makes sense that her approach has amassed a virtual following of more than 53,000 in the last year alone.

Tiffany Baskett agrees with the need for spaces where Black bodies are affirmed and accepted, minds are shaped, and souls liberated. The Atlanta-based owner of runs a multidisciplinary studio that鈥檚 only five minutes from where she went to high school. Baskett bridges working in the community with studio ownership.

鈥淚 get the opportunity to share the healing powers of yoga in the place where we feel most comfortable鈥攐ur own backyards,鈥� she says. 鈥淥verall, it鈥檚 worth it to me to help create a ripple for generational healing,鈥� says Baskett.

The Quest for Community

For many teachers from traditionally marginalized backgrounds, sharing yoga strategically within the community is in service to personal and collective liberation.

鈥淏elonging, community, and uplift are exactly why Black Yoga Teachers Alliance Facebook group was established in 2009, and why it was incorporated as a in 2016,鈥� says Dr. Parker. 鈥淎lthough it is documented that Black yoga practitioners in the United States have been around since the early 1920s, we haven鈥檛 always been acknowledged. The Facebook group and organization were formed to create a sense of community in response to Black yoga teachers鈥� feelings of isolation and feeling invisible in the larger yoga community.鈥�

When the question 鈥淲hat is your biggest challenge as a yoga teacher?鈥� was posed in the BYTA Facebook group, the overwhelming response was the feeling of isolation. Baskett asks, 鈥淚f I didn鈥檛 open a studio as a Black woman who cares about Black people, who would?鈥�

Providing for ourselves has historically been a motivating factor to organize and create within the Black community. Yet it could also be a contributing factor to the lower numbers of studio ownership.

The Role of Religion

Culturally, there are still problematic conflations of yoga as religion or as a function of religious dogma that preclude many from practicing yoga.

But is yoga synonymous with hinduism and is hinduism the foundation of yoga?

鈥淵oga predates organized religion,鈥� explains , a yoga educator and Board President of the Accessible Yoga Association. The recontextualizing of yoga鈥檚 expansiveness, a movement being led by South Asian voices, is helpful for Black yoga teachers who are working toward an inclusive lens of sharing the teachings of yoga.

As the American Black聽 community is 76 percent Christian, Black yoga teachers often find themselves as educators about yoga鈥檚 connection to a broader spirituality and philosophy that is inclusive of any religious practice. Arguments and accusations of blasphemy regarding teaching yoga sutras rather than Bible scripture are rife within the Black yoga community. Clarifying yogic studies as philosophical study helps bring spaciousness to a constrictive understanding of yoga.

Rao asserts that the 鈥渞eligious fundamentalism prevalent in yoga spaces should be dismantled.鈥� Her work includes offering critical indigenous insight into the yoga stories and histories that have been obscured by Brahminism, heteronormative patriarchy, and colonization.

Isolation Takes Many Forms

The isolation experienced by people of color in yoga spaces can be seen as parallel to the isolation of the Black population on a larger scale. Historically and statistically, the Black population faces inequitable access to healthcare, education, and land. Because structural racism exists, reduced access to desirable land ownership also exists, thanks to redlining and eminent domain , particularly in wealthier neighborhoods.

A sobering statistic from the 1990 census showed that 78 percent of White people lived in predominantly White neighborhoods. That shifted to 44 percent as of the 2020 consensus (), yet affluence remains largely unchanged. Black Americans represent just 1.7 percent of the population in the wealthiest neighborhoods in the country ().

Studios usually lie within wealthier neighborhoods, with some such as in St. Louis and in South Los Angeles. Because affluence and race are, unfortunately, still tethered, yoga studios and practitioners of color are driven apart.

When Black yoga teachers and practitioners teach at studios, they are largely going outside of their communities鈥攂oth in terms of location and identity鈥攖o practice and teach. At a recent training I attended, a yoga teacher lamented that most yoga teachers of color can鈥檛 afford to live in the areas in which they teach. This creates other problems that call out traditional social positioning of power, such as the potential for yoga teachers being seen as service personnel. It also creates a vacuum of yoga intellect being extracted from one part of the city into another.

Systemic Inequality Plays a Role

Brooklyn-based , a yoga teacher and financial wellness consultant, cites access to capital as a primary barrier to entry for owning a yoga studio. Studio owners have to be willing to not make money for a long while. 鈥淪mall businesses don鈥檛 really make money for the first five years,鈥� explains James. 鈥淣ot everyone can afford not to pay themselves, which is common, because they pay the team first.鈥�

For Black yoga teachers who do endeavor to own studios, lack of generational wealth leads to the necessity to find funding, which introduces other unfortunate statistics. Black business owners are less likely to receive funding from financial institutions, according to the . Of the $215 billion in venture capital raised by companies in 2022, just one percent of those startup dollars was allocated to Black founders, according to .

James states that it is essential that studio owners, like any small business owner, find other sources of revenue to sustain the business. 鈥淥ne has to understand what is the real cost of running the business and how one supports oneself when the revenue isn鈥檛 coming in.鈥� For a community that is already at a disadvantage for access to funding, the quest for financial security could mean finding an alternative method of delivering the teachings.

The Realities of Studio Ownership

The typical studio model is not one to which all aspire, especially when it鈥檚 not necessary to share the practice of yoga.

鈥淚 feel that some of the joy would get mired in the grind of making the rent, paying a staff, etc,鈥� states Ashley Rideaux, a sought-after LA-based teacher trainer for Center for Yoga LA and creator of her own online platform.

鈥淥wning a traditional yoga studio has never been of interest to me,鈥� she explains. 鈥淚 love showing up for students, holding space, and teaching. Of course, there is still the business side of things when it comes to running my own online platform, but the overhead isn鈥檛 overwhelming, which means I am able to offer my classes at a rate that is more accessible than the average studio.鈥�

This is hugely important to Rideaux, as yoga has become more and more cost prohibitive throughout the years.

Crystal Wickliffe intentionally shares yoga through offering retreats instead of working at a yoga studio, much less owning one. 鈥淗osting retreats allows me to creatively design how I want to show up in the wellness space and gives me agency over my time,鈥� says the Houston-based certified yoga teacher and creator of .

鈥淚 know better than to never say never鈥ut as yet, I have no desire for the overhead nor trusting the fickle nature of the human condition as a means of serving dharma,鈥� says Hubbard. Working from nearly anywhere allows him to engage meaningfully without needing a large physical space. 鈥淚 personally never saw the business sense in seeking to operate according to the traditional model,鈥� he says.

Although the playing field appears to have been leveled with yoga studios鈥� ability to operate fully online, the new challenge is finding one鈥檚 community in a very crowded space. Without even addressing financing the necessary technology to make for a strong user experience, investing large amounts of money in marketing creates the same inequities as rental space. This may not present a barrier to entry, but rather a barrier to survival.

Collective Care and Personal Liberation Are Not Limited to a Yoga Studio

The incredible amount of labor required to establish and run a studio in the face of financial, cultural, and historical pressures provides context to why so few yoga studios are owned by Black yoga teachers.

Yet, there are those of us doing it because it鈥檚 important and we love it. From my experience, having pivoted to a studio community that is intentionally BIPOC-affirming provides all of the nurturance and belonging that I hoped for, but never truly found, in other places.

Tiffany Baskett concurs. Baskett鈥檚 students have shared that they have somewhere where they can explore alternative ways of being, ask questions and be in observation mode. Baskett stresses how important it is for the Black community to have a place where they can let go, do more, and rest.

鈥淭hey get to walk into a sacred space curated by someone who looks like them and has them in mind,鈥� says Baskett. Seeing oneself in the teacher, studio community, and ownership empowers people who have a shared experience of erasure and isolation. 鈥淚t brings me joy to hear how beneficial having somewhere to feel at peace has been for them.鈥�

While it is an act of profound resilience to bring yoga to a larger community in spite of, and alongside, these issues, what would be better is not to have to be so resilient. A yoga community that practices self study is likely becoming curious about these disparities.

But also, maybe many of us just don鈥檛 want or need to own yoga studios because we don鈥檛 have to. Collective care and personal liberation aren鈥檛 limited to traditional yoga studios. Whether or not yoga takes place in a studio setting, there is hope for more expansive yoga spaces throughout America.

In the meantime, Black yoga teachers and students will continue to find one another in various spaces as we create expansive ways of experiencing our bodies, breath, and being.

About Our Contributor

E-RYT 500, curates yoga experiences and trainings in service of collective healing and community repair. Having begun her yoga journey in 2001 with a home practice, she now holds advanced certifications and training in Trauma-informed Yoga, Somatics, Yin Yoga, Restorative Yoga, and Yoga Nidra. Tamika鈥檚 journey has been informed by chronic pain and injuries, social justice for QTBIPOC communities, the battle between shame and compassion and quest for ancestral healing, and the love for the practice and philosophy of yoga.

The post Where Are the Black Yoga Studio Owners? appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

A collection of profiles highlighting different voices in snow sports

The post Our Favorite Ski Stories in Honor of Black History Month appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

To celebrate Black History Month we鈥檝e rounded up some of our favorite stories that highlight diverse voices.

Historically, skiing has been a predominantly white sport, which makes it more important than ever to highlight new faces in the industry. Through perseverance and passion, these individuals are breaking barriers on the slopes and helping to foster a more inclusive and welcoming environment within the skiing community.

I met Stan Evans in the winter of 1998 when we were on one of our first feature assignments for a new ski magazine devoted to the wild and aberrant freeskiing movement that was taking off as a ski subculture. This made us misfits by choice, and while I wasn鈥檛 aware of any other Black ski photographers, it didn鈥檛 occur to me that there was anything historic about our assignment. The following winter, Stan organized and produced the first snowboard magazine story featuring all Black riders, shot by a Black photographer. That this had never been done makes it objectively historic, and it stands as a benchmark of winter sports diversity. At the time, however, very little mainstream attention was paid to the quantum gap jump that Stan had just helped the sport clear.

A few months into the pandemic, 鈥渟heltering in place鈥� meant living in my van in Bend, OR. Having recently lost my previous job as an outdoor industry sales rep, I decided an escape into the backcountry might help me regain control of my spiraling anxiety.

Stratton Matterson organized a small crew, including Zak Mills, Ian Zataran, and myself. Our goal was to circumnavigate Oregon鈥檚 second-tallest and least-explored volcano.

Over three nights and four days, we unplugged from the chaos of the world while traversing our way across the mountain鈥檚 various aspects. We skied thousands of feet of perfect corn snow, traversed crevassed terrain, filled our water bottles in glacial creeks, and rested our weary bodies on warm lava rock. Rockfall echoing through the mountain鈥檚 canyons was our soundtrack.

, a Bend, Ore.鈥揵ased skier, and filmmaker, decided to throw out the rulebook with 鈥淭he Blackcountry Journal,鈥澛�a short film that mixes backcountry freeskiing with his lifelong passion for jazz. Beneath the smooth soundtrack and savory facade is a complex story about race in skiing, although the nuance may take a few views to rise to the surface. Shot in monochrome and structured in three parts, the film abstractly follows Duncan鈥檚 story as a black man trying to find his place in the white ski industry.

We sat down with Duncan upon his return from the Banff screening to learn about the making of 鈥淭he Blackcountry Journal.鈥� Be sure to聽聽when it鈥檚 released to the public on Nov. 8.

On a spring morning at Vail, laughter fills the entire dining room of a restaurant lounge as a group of people gather around a stone fireplace. They clap one another on the back, cackling to inside jokes and generally enjoying each other鈥檚 company. At first glance, you might think you鈥檝e stumbled into a reunion of some sort.

The truth is, most of us have just met each other this morning, brought together by an organization whose mission is to encourage, teach, and inspire Black, Indigenous, and people of color to participate in mountain sports by creating spaces for enjoying the outdoors. This convivial group is here for a ski day with the Denver-based 听(叠惭颁).

An Oral History of the National Brotherhood of Skiers

The nation鈥檚 first Black ski group, the Jim Dandy Ski Club (named after an R&B song by LaVern Baker), formed in Detroit in 1958. By the early 1960s, a handful of U.S. cities had similar clubs, like the Snow Rovers in Boston and the Chicago Ski Twisters. In New York, there was the Four Seasons Ski Club, run by an NBC cameraman named Dick Martin, who owned a ski shop in Harlem and often played ski evangelist to his peers, screening films and proclaiming that a skier need not be a 鈥渂lond-haired, blue-eyed Norse god.鈥� Martin organized weekend ski buses that rolled out of Manhattan at oh-dark-thirty to wend their way north to the mountains of upstate New York. In 1964, a 25-year-old New York University graduate student named Ben Finley climbed on board.

Soft Life Ski, has a unique mission built on a combination of unlikely passions: skiing and Afrobeat music. The UK-based group hopes to increase inclusion and diversity in the winter sports space by organizing music-themed trips to ski resorts. 鈥淪oft life,鈥� a term for an easygoing and relaxing lifestyle, is the feeling the group hopes to bring to the slopes. In short, SLS is a traveling music and ski festival aiming to introduce the joys of winter to its Black and African audience.

The post Our Favorite Ski Stories in Honor of Black History Month appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

We chatted with Kai Lightner about diversity in the climbing world misconceptions about how accessible climbing is for people of color, and his nonprofit, Climbing For Change

The post Kai Lightner Thinks We Can Do Better appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

Though he鈥檚 just 24 years old, Kai Lightner has been a kitchen-table name in the rock climbing world for more than a decade. After years of steady performance in the competitive youth circuit, Lightner took the outdoor world by storm in the spring of 2013, when during a four-week period he sent his first four 5.14s鈥攊ncluding Southern Smoke (5.14c). He鈥檚 been in and out of the headlines ever since, climbing other hard 5.14s, winning a Youth World Lead Championship, and taking multiple golds at both Youth and Open Lead Nationals.

But talent wasn鈥檛 the only thing that set Lightner apart: he鈥檚 also Black. And as one of the first African American climbers to reach such a high level in the sport, Lightner found himself something of a poster-child for diversity in the climbing world, and the outdoors more generally. Yet while he won comps and acquired sponsors, appeared in Reel Rock segments and major corporate ad slots, Lightner鈥檚 experience with the wider climbing community was鈥� complicated.

In straight terms: 鈥淲e encountered a lot of bullshit,鈥� Lightner remembers.

Meanwhile, members of the climbing world used him and his accomplishments as evidence that climbing didn鈥檛 have a diversity problem鈥攕omething that does justice to neither the demographic facts nor Lightner鈥檚 experiences in the sport. 鈥淭here were multiple points in my career where I was like, 鈥榃ell, we鈥檝e reached the end of the road,鈥欌€� he told me in an interview in March 2023, 鈥渂ut then, miraculously, something would come up and it would help me push through. So I find it funny when people use me as an example of diversity in the sport. Because I am not the rule, I am an exception鈥攁nd I barely got here.鈥�

While in college, Lightner chose to step away from competitive climbing, at least temporarily. 鈥淚鈥檝e always wanted to look at how I could impact the community in a more holistic way, but when you鈥檙e in the grind training for competitions, you鈥檝e got to have your head down. College gave me the opportunity to lift my head up a little bit, see what I could offer the climbing community.鈥�

Then, in the summer of 2020, while Lightner was still a student at Babson College, George Floyd was murdered. Suddenly Lightner found himself the corporate climbing world鈥檚 鈥済o-to person鈥� for anything pertaining to race in the outdoor industry. 鈥淭here I was behind the scenes,鈥� Lightner remembers, 鈥渉elping [companies] craft their DEI statements鈥� and I realized I could be more effective if I organized this work under an organization like .鈥�

We about Lightner when he launched Climbing for Change, a 501c3 nonprofit devoted to expanding diversity across all levels of the climbing community, in late July, 2020. But that was a long time ago. So we thought it was time for a catch up. In our conversation, which has been condensed and edited, Lightner talked about his own experiences with racism in the climbing world, blew apart some common misconceptions about how climbing is accessible for people of color, and, in spite of it all, expressed a real and honest optimism about the future of diversity in the outdoor industry. We also talked about how Climbing for Change has evolved over the last two and half years and鈥攐f course鈥攁bout his current climbing and training goals. (Hint: no comps!)

INTERVIEW

Climbing: Let鈥檚 start with your early years: What was it like to be not just a very good rock climber at a very young age, but a very good rock climber in a sport where there really weren鈥檛 many other Black athletes?

Lightner: It was difficult in a lot of ways. I did a lot of questioning of my identity. On the one hand I enjoyed this sport so much, but on the other hand, it was a sport that had made itself pretty exclusive to people who looked like me. When I told people that I liked to go rock climbing, people questioned my Blackness, people questioned my sanity, and my family questioned my safety. So it was scary in the beginning. And we encountered a lot of bullshit that made me question whether I belonged.聽

One thing that people don鈥檛 always appreciate is that, sure, there are plenty of people without jobs or a steady income who make climbing and travel work on a shoestring budget鈥攂ut doing that requires community, it requires access, it requires knowing people who also do the sport. But if you don鈥檛 know anyone, and you don鈥檛 know the gear, and you don鈥檛 know where to camp, and you have no history of entering communities like this, it鈥檚 really difficult to piece things together enough to get started in sports like climbing.聽

The only way I made it in the beginning was that people saw my talent as an athlete and helped me along the way. There were multiple points in my career where I was like, 鈥淲ell, we鈥檝e reached the end of the road. We can鈥檛 afford to do more. This is it.鈥� But then miraculously something would come up and it would help me push through. So I find it funny when people use me as an example of diversity in the sport. Because I am not the rule, I am an exception鈥攁nd I barely got here. So I understand fully why there are not enough people of color in the sport, and that鈥檚 why I鈥檓 trying to close those gaps and give opportunities to people like me.

That actually reminds me of the book publishing industry in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s: it was wildly undiverse back then (and still has work to do) but people kept saying that this lack of diversity wasn鈥檛 a problem because Black writers like Toni Morrison and James Baldwin and Jamaica Kincaid were getting published and winning prizes. Do you feel like that鈥檚 something the climbing community has done with you鈥攍ike: 鈥淥f course we鈥檙e a diverse sport. We鈥檝e got Kai Lightner鈥�?

I think history repeats itself. And I definitely think that I鈥檝e been used to promote the message that the sport is diversified despite the underlying lack of diversity. As one of the only professional African American climbers, when people are trying to promote that message, my literal image gets used鈥攂ut it鈥檚 just not telling the whole story.聽

This is not solely a climbing world problem. People use Barack Obama to say that the country is no longer racist. People use singular examples of Black excellence as examples that the whole system is changing, just because that one person made it through. I mean, we hope that that person opens doors in the future, but these people are the exceptions, not the rule. And the fact that nearly every one of them has a ridiculous story of extreme tenacity shows that the barriers are still hella high. They鈥檙e getting attention because they are exceptional, but why are they exceptional? Because they stand alone. We have a lot of work to do to make success like that more consistent.

Have you seen significant DEI change since you started climbing or is the record more mixed?聽

I think that there鈥檚 been good work done, but I also think that there鈥檚 continued work that needs to be done to make it sustainable and fully impactful. We鈥檙e seeing more marketing and ad campaigns featuring diversity, but it would be nice to see more people of color in positions of leadership and power where their voices can be a little louder. So there鈥檚 work to be done. But the initiative and conversation is there. I mean, ten years ago this wouldn鈥檛 even have been a conversation. So there鈥檚 been progress in that respect.

What have you identified as some of the biggest barriers that our community faces when trying to make the sport more diverse?

The big ones we鈥檝e tried to hop over at Climbing for Change are cost, access, and stigma. It鈥檚 expensive to participate in these sports. And not everyone can visit these areas or feel safe when they do. A lot of the outdoor areas that climbers celebrate have deep histories of racism that have steered people of color away from wanting to recreate there. So I think the work isn鈥檛 just to make the sport more accessible but also to make the wider environment more accepting of people who look like us. And that鈥檚 a big job. I don鈥檛 think in my lifetime I鈥檒l see that fully worked through. But it鈥檚 got to be chipped away at somehow. And that鈥檚 the job I鈥檓 taking on at the moment.

When did you first decide to start Climbing for Change: it was in 2020 right?

All through my career I鈥檝e done grass-roots community work, trying to make outdoor recreation more popular and available to communities of color, but in 2020, when the Black Lives Matter movement was going on and there were all these tensions, I became everyone鈥檚 go-to person for PR statements or business advice. Companies were asking me 鈥淲hat have we done wrong鈥� or 鈥淲hat can we do better? How can we help?鈥� and there I was, behind the scenes, consulting with companies, helping them craft their DEI statements or allocate funding. And I realized I could be more effective if I organized this work under an organization like Climbing for Change.

What were the organization鈥檚 early days like?

So in July 2020 we got a 501c3 and hit the ground running. We launched a few grant programs and our first physical program, in Atlanta, working with the local government and Stone Summit Climbing gym to create a sustainable access point to climbing for local communities of color. We used city resources to provide free transportation to the gym, and we partnered with Kevin Jorgeson and to build a climbing wall at a recreation center in College Park. We were able to do that within six months of launching. Which was God鈥檚 work, trust me. It was a lot of effort.聽

How have things gone since then?

Since January 2021, we鈥檝e been able to work with our high profile donors like Clif Bar, Adidas, and Black Diamond to offer 10 different grant programs, each of them targeting different aspects of diversity in climbing. We鈥檝e awarded over $136,00 in grants to 87 different individuals and organizations. And we鈥檝e consulted with countless small businesses in the outdoor industry. We want people of color to look at this space and not just see themselves in the people climbing or skiing or hiking with them; we want them to be greeted at the door by people who look like them, see ad placements featuring people who look like them, and see people at the top making the decisions who look like them.聽

What are some of those grants like?

Our mission statement, our goal, is to diversify the outdoors from top to bottom. targets a different part of that mission statement, but I鈥檒l highlight three of them. The first is the , where we aim to encourage BIPOC individuals to become leaders in the outdoor industry. In doing that, we鈥檝e been able to help 31 people get route setter certificiations, single pitch instructor certifications, wilderness first responder certifications, and so on. These certifications help them become leaders and guides who can help others get outside. Through that grant, we鈥檝e also funded some big projects like the Black Out Fest, which is the only festival in the United States that focuses on celebrating Black people in rock climbing, and the FAMU , which is the first outdoor club at a Historically Black College or University.聽

We also have our , which helps individuals move from indoor to outdoor climbing鈥攕omething that I know from experience is a big leap. In that process we were able to fund 14 people to attend the at Ouray earlier this year. And we sponsor groups from places like to do outdoor bouldering trips outside.

The third one I want to highlight is our Project Based Opportunity Grants, sponsored by Adidas, which provide a conduit for corporate organizations to get talent from diverse pools of people. One of the big complaints we heard in 2020 was companies saying that they didn鈥檛 know where to find more diverse employees. But if you鈥檙e still pulling talent from Primarily White Institutions or spaces that don鈥檛 have any history of diversity, you鈥檙e not going to have a large pool of people to pull from. You need to be looking at HBCUs, or career fairs in diverse communities, places where intellectuals of color congregate. So with the Project Based Opportunity Grants we鈥檝e tried to help bridge that gap, working聽 with HBCUs and other diverse organizations to create job opportunities.

You鈥檝e devoted a lot of your life to being a great climber and expanding that sport for other members of your community. How do you pitch climbing to non-climbing communities who might be distrustful of it for those reasons you mentioned above?

Climbing is a lifelong relationship, not just with themselves and the sport but with nature in general. And it teaches so many fundamental lessons. Even as a kid I had to learn important adult lessons through climbing, such as how to transfer your failures into learning experiences, or how to slowly chip away at a goal that is too big to fathom at the moment but will slowly become possible as you improve.聽

It also teaches you a lot about community. At every level you鈥檙e relying on someone else. When they belay you or spot you, your life is in their hands, and that helps develop a level of trust that can break down certain barriers. When you鈥檙e putting your life in someone鈥檚 hands, it doesn鈥檛 matter what color their skin is or what kind of background they have. Instead you see them for who they are. And I think that鈥檚 not something that a lot of other sports give you.

Climbing also gives you a level of physical and mental focus that really helps with self esteem. A lot of the grants we give out with Climbing For Change are to people with PTSD or ADHD, and for some of these people, climbing is the only thing that helps them focus and center themselves in life. Because not only do you need to be physically engaged while climbing, you鈥檙e constantly also problem-solving in real time.聽

Lastly, I just think that climbing is a super holistic, lifelong, special sport. You know, it鈥檚 crazy: I鈥檓 not competing anymore, but I feel like my work is just beginning. There are so many genres of the sport. You鈥檙e never finished with climbing. And as you get older, you develop newer skills and can lean on different aspects of your physicality and mental game; you become mentally stronger and technically sounder. A lot of the best climbers I have been in the sport for decades and have so much to give to the next generation.

What’s聽your climbing like these days? Are you training for comps or for outdoor goals?

I鈥檓 not currently training for comps. I鈥檓 old. [Laughs]. But seriously, if I stepped back into competitions, I鈥檇 be one of the oldest in the room. So my calling and focus has been outdoor climbing. I graduated from college in May of last year, and I spent the summer and fall focusing on Climbing for Change. But I鈥檝e been training all through the winter, and now that spring is coming I鈥檓 really excited to test myself outside in a way that I haven鈥檛 been able to before. Most of my outdoor climbing before now has been in short windows of time, during spring break or fall break, in between school and competitions. But now I have the time, so I鈥檓 going to do a trip to Spain, and I鈥檒l do some trips to Colorado to try some multi-pitch climbing. But I also just want to climb outside more often and get used to regularly being in the dirt, because I鈥檓 not used to it at all.

Has your training changed with that new focus?

Funnily enough, it鈥檚 changed quite a bit. With comps, you鈥檙e really training all different types of skill sets. You basically have to walk into a competition with a full toolbox even though you know that you will only need to use two or three items in it. Whereas if you have an outdoor project, you can study that project, train for that project, and come prepared for what you need. That鈥檚 a very different mindset for me, but it鈥檚 been very fun. Outdoor climbing also puts more emphasis on muscle memory and learned movement rather than walking into a comp over-prepared and super strong and hoping that it works out. It鈥檚 a bit more predictable, which I can appreciate.

Anything you want to add?

Climbing for Change also accepts through their links. No donation is too small. One dollar, five dollars, ten dollars. The only way that we can provide the grants that we give is through the money we get through donations. It鈥檚 accessible on the website.聽聽

Steven Potter is a聽digital editor at聽Climbing. He鈥檚 been flailing on rocks since 2004, has successfully injured (and unsuccessfully rehabbed) nearly every one of his fingers, and holds an MFA in creative writing from New York University.

The post Kai Lightner Thinks We Can Do Better appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

The short movie premiered at 5 Point and Banff Film Festival this fall, subtly questioning what a ski edit can be

The post 鈥楾he Blackcountry Journal鈥� Turns the Traditional Ski Film on Its Head appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

Let鈥檚 be honest: There鈥檚 a tried-and-true formula that most ski movies follow. A group of heroes is on an all-too-familiar quest, then cue the slow-mo slashes, steep spines, and stylized shots 鈥� and repeat until the end. It can all blur into one long segment at times. And that isn鈥檛 necessarily a bad thing鈥攚e love a shreddy stoke film as much as the next person鈥攂ut we can all agree that it gets repetitive at times.

, a Bend, Ore.鈥揵ased skier and filmmaker, decided to throw out the rulebook with The Blackcountry Journal, a short film that mixes backcountry freeskiing with his lifelong passion for jazz. Beneath the smooth soundtrack and savory facade is a complex story about race in skiing, although the nuance may take a few views to rise to the surface. Shot in monochrome and structured in three parts, the film abstractly follows Duncan鈥檚 story as black man trying to find his place in the white ski industry.

We sat down with Duncan upon his return from the Banff screening to learn about the making of The Blackcountry Journal. Be sure to when it鈥檚 released to the public on Nov. 8.

SKI: Welcome home! How are you?

Mallory Duncan (MD): I鈥檓 doin鈥� alright. Life is chaos right now. I鈥檓 juggling a lot, getting ready for the digital launch. I鈥檝e been handling all the post production, from festivals to distribution. It鈥檚 been a huge learning experience, but also exhausting. I just got back from screening it at Banff this weekend, along with a bunch of films from CK9 and Level 1, and that contrast certainly made the film stand out.

SKI: What are a few of the recent lessons?

MD: The biggest one is how to say no. I need some time at my house to regroup. I was gone for three weeks and have more travel coming up, so I鈥檓 grateful for time at home. It鈥檚 all a balance. Also, it feels uncomfortable to promote something this much. That鈥檚 not me. I know it鈥檚 important for the film鈥檚 success and I only get to release my first ski film once, but it feels weird to be posting about it everyday. But, I am proud of what we made and want people to watch it, so I鈥檓 just going for it.

Also Read:

SKI: What鈥檚 the theme of the film?

MD: I have been processing this a lot so I appreciate you asking. It鈥檚 about 鈥渁rtistic鈥� expression. Skiing doesn鈥檛 need to be the gnarliest line or raddest thing. It doesn鈥檛 need to be big, unattainable tricks. Instead of pushing limits, it鈥檚 about expressing myself on a slope. Looking up and seeing art. Developing my own style of skiing. I wanted to make the skiing relatable and focus on the creative aspects of filmmaking. Below that is a story about finding my place in the ski industry as a black man, but I didn鈥檛 want the race part to be heavy handed. You鈥檒l either pick it up or you won鈥檛, and either is okay with me.

SKI: The film is based around a couple poems you wrote; what are the most important lines?

MD: The first poem I wrote in late 2020 and it was the catalyst for the film. The second poem, the one that the film ends with, has been more impactful recently. One of my favorites I thought of while skiing Mount Jefferson. 鈥淒id you feel the rhythm of the wilderness, while you rested on a rocky shoulder, the beat of rock fall reverberating off the canyon walls.鈥� It was a beautiful moment and it needed to be in the film.

Another is about appreciating the art left on the slope. 鈥淲hen you look back, didn鈥檛 you see the piece you played, improvised on the peaks鈥� paper flanks.鈥� I love the alliteration of it. Making the film based on the poems helped me connect to skiing in a new way. I hope that it inspires others to express themselves too.

SKI: What other films did you use as inspiration?

MD: One in the ski world and one is not. The first is . It鈥檚 an experience just watching it. You can feel that energy without any words. I wanted to do that with The Blackcountry Journal. The second is by Topaz Jones. He鈥檚 a hip-hop artist and calling it a visual album doesn鈥檛 do it justice. It鈥檚 powerful because it can be interpreted in so many different ways. It鈥檚 a form of black art, by a black filmmaker, about black identity without putting it right in your face. I appreciate the subtly.

SKI: How does race play into your film?

MD: I wanted to show that black people have a place in skiing, not tell people how they do. I like to be about things, not talk about them. I live a black experience, but that doesn鈥檛 define me as a skier. While I will never deny my blackness, I don鈥檛 have to force it into conversations either. Just by existing in these spaces I am part of the movement for more representation in snow sports. It鈥檚 better to show, not tell.

SKI: Is there anything would you have done differently?

MD: There鈥檚 a lot of small tweaks and edits that I could obsess over for the rest of time, but generally speaking I鈥檓 really stoked on where it landed. Honestly. Sometimes I wish we added some of the bigger lines we skied in Alaska, but our goal was about the expression of the sport, not proving I鈥檓 a good skier. The open, mellow glacier skiing is where you really get to improvise and I鈥檓 happy we stuck to that.

SKI: Are you inspired to do more filming after this is behind you?

MD: Absolutely. I want to continue telling stories about skiing in a unique way, drawing connections to urban culture, music, and hip hop culture. We鈥檙e throwing around a lot of ideas right now and I can鈥檛 speak directly to them yet, but as someone who grew up in the city, I see an opportunity to make more ski films relatable to urban folks. I want to talk about skiing in a way that brings more people into the sport.

Watch The Blackcountry Journal on YouTube

The post 鈥楾he Blackcountry Journal鈥� Turns the Traditional Ski Film on Its Head appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

Fearing racial violence, the Colorado trail runner turned to her network of athletes. Their support helped her move forward with pride.

The post Kriste Peoples Knows She Belongs appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

Kriste Peoples told her story to producer Tunvi Kumar for an episode of The Daily Rally podcast. It has been edited for length and clarity.

So around that time, I’m running through the neighborhood, and I have these events on my mind, these murders. I’m running through my wealthy neighborhood, and it occurs to me that I can’t run on the sidewalk, because if I run up on a white woman with the stroller, or carrying a purse, or just walking, then that could seem threatening. Somebody can look out their window and call the police on me. And if I go into the street, then I can’t run near the driver’s side door, lest somebody think I’m trying to break into their car.

It’s not safe to be anywhere in this Black body in America.

I am a trail runner. I am a writer. I am a program director at Women’s Wilderness, which is a nonprofit based in Boulder, Colorado.

When I moved to Boulder, where there are mountains all around, it was a brand new world to me, because I had grown up on the east coast, where we had beaches and flat land. I felt like some of what I was reaching for was kind of hard to find, it was like hunting around in the dark. Being able to demystify the process of getting outdoors and finding people to go with was huge.

Finding running brought me so much relief and release. Simply running. In the backcountry or running trails, sometimes people would say, Black people more often than not, 鈥淎ren鈥檛 you afraid out there of the wild animals?鈥� And, 鈥淏lack people don鈥檛 do that.鈥�

Then came 2020. There was a mandate called Safer at Home, which said to stay within 10 miles of your home. At the time I was living just beyond 10 miles from the mountains. So that meant rather than going to the trails to run, I was going to be running through my neighborhood, which was wealthy and white. Around this time, we’d experienced the upheaval from the Ahmaud Arbery murder. This was a young Black man who was running in Georgia, and was targeted and gunned down by some people who thought he shouldn’t be there. We’d also had Breonna Taylor’s murder. She was asleep at home in her bed. And the so-called authorities busted in and shot her to death in her sleep.

And I鈥檓 running through my neighborhood, and it occurs to me, I can鈥檛 run too fast, that might draw suspicion because perhaps someone thinks I鈥檓 fleeing the scene. If I run too slow, perhaps they think I鈥檓 casing the neighborhood, looking to come back and do some harm or steal or whatever. And so it鈥檚 really top of mind for me.

A lot of the benefit that I get from running is clearing my head, helping to make sense of the world around me. So, it was a really challenging time, because it made me feel like, Well, there is no safe place.

Among our trail running group, we were having a Zoom conversation about running, coaching, what’s going on with us. We have somebody talking about nutrition, somebody else talking about gear, and then I say, 鈥淵ou know what? Hey everybody, I gotta say that this is a really hard time for me right now, because this Black man has been murdered. He was in a part of town people didn’t think he should be in.鈥� And I am a Black person running on the streets, even though it鈥檚 my neighborhood, and I feel very vulnerable right now.鈥� So, it was really emotional the more that I talked about it. And I said, 鈥淚t is just very hard right now, and I am needing some support.

Our trail running group shared that they too were upset by it and didn’t know what to do. And so being able to have those kinds of conversations was huge, because how often are we really talking to each other about issues that make us feel very uncomfortable? Talking about issues that don’t have easy solutions, and realizing that we don’t know what to do, but being able to even say, 鈥淲e don’t know what to do and we are upset.鈥� Being able to say that and hear each other is actually a way to bond, and to at least become more aware of what’s at stake and how we might try to take care of each other even if we can’t solve the bigger issue.

As we talked, people started offering to run in solidarity and to share about it. And they came forward and supported me by doing some honorary runs to really commemorate the life of Ahmaud Arbery.

What helped me get through that was reaching out to my communities and letting people know if I鈥檓 struggling or if I need support. Another big part of this is, I can ask for that support, but I also need to let myself receive it. And receive it in whatever form people are able to give, because we don鈥檛 always know how to handle each others鈥� pain and confusion.

Running together will not cure racism, and will not keep people from thinking that I do or don’t belong in certain places. But being able to share with people means that I don’t have to hold the pain alone. That empowers me. That fuels me, because I know I鈥檓 not just one lonely powerless person out here just trying to live a life with some modicum of happiness.

A lot of people do have the experience of feeling like they鈥檙e not qualified to be outside, or that they don鈥檛 belong outside, or that there鈥檚 no room for them, or they don鈥檛 see themselves represented outside. And up until very recently, the media wasn鈥檛 showing people of color in the outdoors. So, I’m still very much running a lot, and I’m out in nature a lot, and I’m still taking people out, and I’m talking about it. I鈥檓 very much engaged, and so wherever I go, I go with the understanding that I belong, that I have a right to show up, that I have a right to my dignity. And I also go with the understanding that it might make people very uncomfortable that I show up, but I can鈥檛 live my life in response to the potential that someone鈥檚 not going to like me showing up in a particular place.

I know that generations of people before me have fought and died for my right to show up in these places. That empowers me. I know that I am somebody鈥檚 dream, I am a great many peoples鈥� dream, and it鈥檚 important to remember that, and to lean into that whenever I鈥檓 feeling a bit tentative. If I鈥檓 going, I need to go with pride, because I don鈥檛 come from nothing. I come from strength.

Kriste Peoples is an outdoor enthusiast, guide, runner, writer, and mindfulness meditation teacher. She serves on the board of the and . When she鈥檚 not adventuring in Colorado鈥檚 Front Range, Kriste is likely recovering with carbs in a local eatery. You can find her at her website and on Instagram .

You can follow聽The Daily Rally听辞苍听,听,听, or wherever you like to listen. and to be featured on the show.

The post Kriste Peoples Knows She Belongs appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

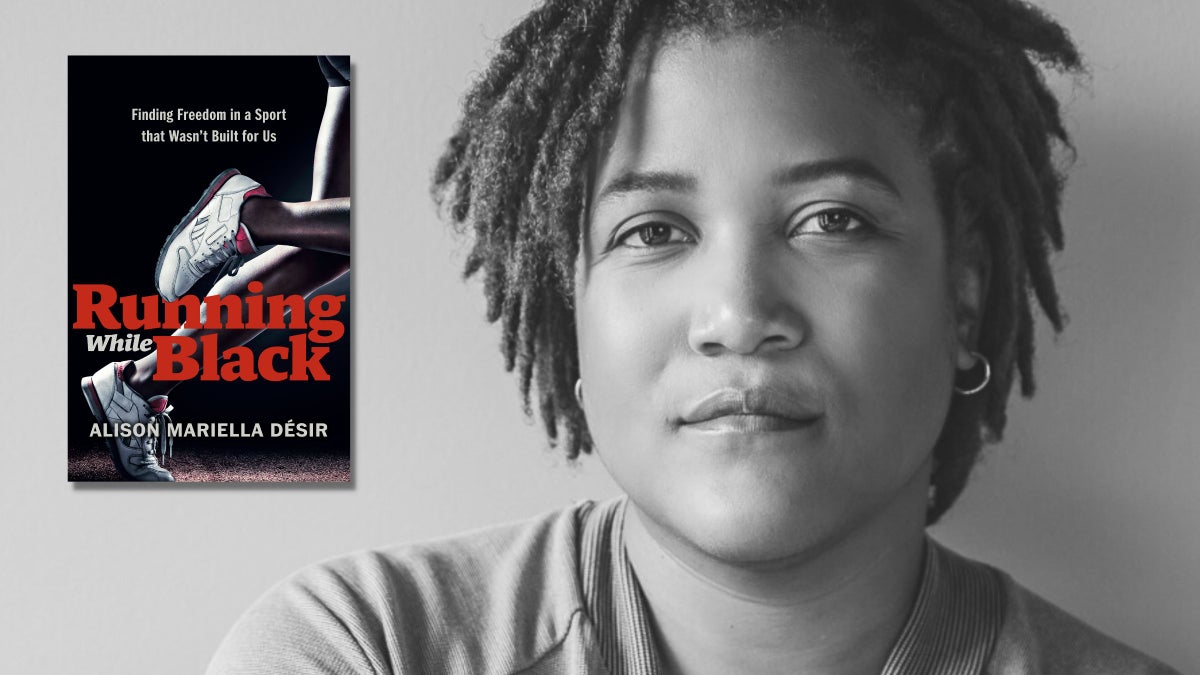

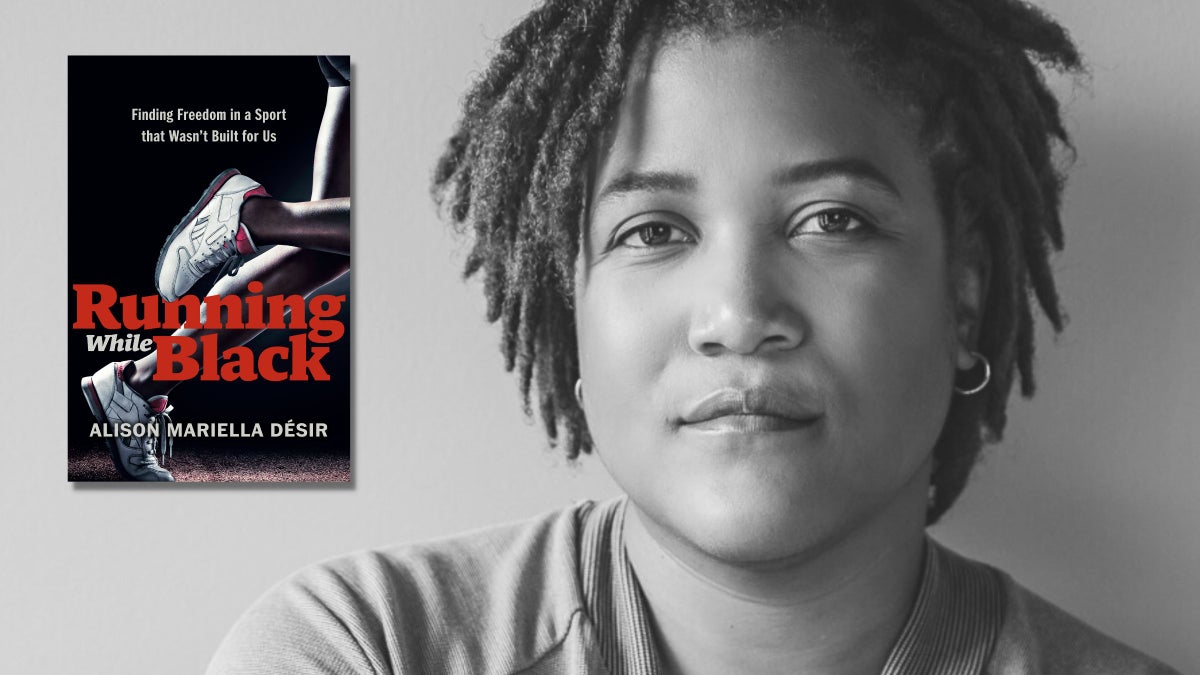

Alison D茅sir to chats about freedom through movement, and creating space for lightbulb moments in her new book Running While Black.

The post With Her New Book, Alison Mariella D茅sir is Owning Her Role as a Running Industry Disruptor appeared first on 国产吃瓜黑料 Online.

]]>

Anyone who has regularly consumed running media over the last couple of years is undoubtedly familiar with the work of activist, advocate, and self-avowed 鈥渄isruptor鈥� . In addition to founding New York City club and the movement supporting women鈥檚 reproductive rights, and serving as co-chair of the , D茅sir has published her highly anticipated memoir, , which will be released Oct. 18. D茅sir sat down with Women鈥檚 Running to discuss the inspiration behind the book, how her personal running story is intertwined in it, and her hopes for the future of the sport with regard to inclusivity among people of all marginalized groups and genders.

Women鈥檚 Running: Congratulations on the release of Running While Black. I feel like I鈥檝e known you and followed your story for such a long time, yet still learned so much about you as I read through it. Can you share how the book came to be?聽

Alison Mariella D茅sir: I鈥檝e always wanted to write a book and had made many previous attempts at writing manuscripts over the years. Many of them are very difficult for me to even look at now because they were focused on mental health and the period of depression I experienced, which I also discuss in this book. I was attempting to write all those manuscripts while I thought I was better, but I still was very much in a dark place. Once you start feeling better and start taking care of yourself, you can鈥檛 even believe that that was once who you were.聽

This particular book came about in 2020, after I had an op-ed published by 国产吃瓜黑料 titled 鈥�Ahmaud Arbery and Whiteness in the Running World.鈥� What was really unique and what made this book so important to me was having a Black son (Kouri, who was nearly 10 months old when I learned about Arbery鈥檚 murder) and then living through the COVID-19 pandemic. It wasn鈥檛 that police murders of Black men had necessarily increased, but we were in this moment where there was a lot less chatter happening and these murders and vigilante killings were more visible. Thinking about that and thinking about how my son will one day be a Black man compelled me to write this. I had to share that moving through space as a Black body is different from moving through space as a white body and that historically and presently, we have never had access to freedom of movement. I just had to tell that story because it also creates a possibility for change and a new world where my son could be free to run, and free to show up as his full self.

You share so much of your personal story in this book, which resonated with me as a peer to you both in age and as a fellow runner and a woman of color working in this industry. But obviously, this book isn鈥檛 just important for people like you and me to consume. Who would you say this book is for, and who do you hope to see choosing to read it?

There are two audiences for this book and they鈥檙e both big. I, for sure, hope that Black people and other people of color read this and say, 鈥淔inally, my experience is represented in a book.鈥� The complete experience is the joy, but also the pain, the fear, and the 鈥渙therness.鈥澛�

But then what鈥檚 also important is white folks reading this book and recognizing that a world exists beyond their own, which is difficult in a world that鈥檚 rooted in white supremacy and that intentionally centers white people in every situation. It is by design that white people are unaware that Black people and people of color move through the world differently, despite the fact that it has been white people and white supremacy who created the laws and environment and maintained that. So I hope that for white people, it humanizes our experiences without shaming them, and while still offering them ways to take action to do better.

When you first announced that you were writing this book, it had the working title The Unbearable Whiteness of Running. I never thought about it until I took note of the change, but to me, Running While Black is 100% the perfect name for this book because it immediately speaks to and centers your experience, which is one that will resonate with a lot of runners from marginalized groups. How did you settle on the final title?聽

With the original title, the book was more sort of a manifesto and in the category of anti-racist books, which are more instructional and intended solely for a white audience. It was my editor, who is a white woman, who said 鈥淲hat鈥檚 missing here is you.鈥� That made me realize that what鈥檚 always been powerful for me in books is when you can go on a journey with the author when you can understand their worldview and what made them who they are, and then you get on board with their struggles and their way of seeing the world. However, that required me to be a lot more vulnerable than I had ever intended to be, and that鈥檚 where you get these stories from my childhood that build an understanding of who I am.

It almost feels like an honor to be able to have the title Running While Black because that is an experience that Black people and people of color (and white people, too) understand in some way. The name is provocative, and so it鈥檒l get people interested in the book. The harder part was actually coming up with the subtitle, 鈥淔inding Freedom in a Sport That Wasn鈥檛 Built For Us,鈥� because we wanted to make it clear and make sure that people understand using the word 鈥渦s鈥� also lets you know that this is Black-centered, that the 鈥渦s鈥� is me and my people. The whole title allowed me to reconcile the fact that running has brought me so much freedom and joy, but it was never intended with somebody like me in mind.聽

I鈥檝e heard you comment about how one of the biggest challenges you expect in getting white people to read this book or even having these conversations in general, will be getting them to see that this isn鈥檛 about hating white people; it鈥檚 about hating white supremacy. Were you worried the original title might immediately make people defensive and opt not to pick up and read the book?

I think that because white people don鈥檛 learn this concept of white supremacy or whiteness, they鈥檙e not forced to think critically about their identity because they鈥檙e seen as a default. Therefore, something like that simple title is seen as an attack. While I wanted my title to be provocative and confrontational, I didn鈥檛 want people to bristle so much and feel so hateful for the title alone without getting into the meat of what I鈥檓 actually talking about. What I hope I do well through the book is take people on that journey of me asking the questions, 鈥淒o I hate white people? Or do I hate white supremacy? What does that mean, and what are the ways white supremacy and this concept of whiteness actually harm white people too?鈥� I hope this will be a lightbulb moment for folks recognizing that we are all harmed in this system, obviously to different degrees, but it is in our own best interest for all of us to want to rethink how this society, and then on a more narrow level, how our running industry and community function.

I loved reading about how you started Harlem Run. You talked about how in the beginning, you stood alone on a New York City street corner for weeks before people finally started showing up. Most people would easily give up too soon because they would feel like their big idea was a failure. It鈥檚 easy to picture you as the resilient Alison I know now and assume that you were just that determined to make it happen. But I did read the book and I also know that you鈥檙e human and that did leave you feeling somewhat defeated. So what was it that motivated you to keep showing up?

I think it was just that finding long-distance running had been such a pivotal piece of my life. As you said, I think people see me now and it鈥檚 consistent with my life that I am bold and disruptive. But I was also coming from a place where I would stay in my house for weeks, with no reason to even leave the couch. Yes, I had just run this marathon and started to feel good about myself and had gone to counseling, but I was not this person who was taking all of these risks and feeling like certainly it鈥檒l happen. But the fact that running had done so much for me, I just felt like it was my calling. I鈥檓 not a religious person, but perhaps someone who is would say that it was fate or some kind of divine message and I really just felt like I had to do this.聽

A part of my own mental health was also hinging on building this community because I had loved the running experience, but I hadn鈥檛 seen a lot of people like me. So I thought, if only I can create this space, then I can have the best of both worlds. I can have the thing that is keeping me alive, happy, and functional with people who look like me. So there was a lot at stake.聽

Seeing how Harlem Run started from you just wanting people like you to run with, to showing Black people the physical and emotional benefits of running, and eventually, being centered as a vehicle for inclusion and social change, how does it feel to see how much it鈥檚 grown and how much of an impact it鈥檚 had on the running community, now on a national level, over the years?

Yeah, talk about the unexpected, right? Harlem Run has very much followed my own personal growth in terms of recognizing, 鈥淥kay, first, I want to do this to bring other people into the sport like me.鈥� Then recognizing, 鈥淥h, the impact of seeing Black people running through a neighborhood of mostly Black people and how our community was not just our run community of people who show up, our community was this larger community of Harlem.鈥� And then recognizing that the media were interested in this story because I am a Black woman leading this group that centers Black and Brown people, recognizing, 鈥淥h, we are actually tapping into this narrative of who moves and who leads movements.鈥澛�

As my own development happened, Harlem Run sort of came with me. I think another critical piece of this is recognizing that there was this industry and that these messages weren鈥檛 just falling from the sky; that there is an industry that perpetuates and fuels these messages, whether it鈥檚 magazines, podcasts, retailers or brands saying, 鈥淥h, there are people who are creating this, and sometimes we fit into the narrative that they want and sometimes we don鈥檛.鈥� But what if we were able to actually take control and be part of creating a new narrative? There鈥檚 so much I didn鈥檛 know was possible and I鈥檓 really proud of it. I love seeing the ways that other groups borrow from what we鈥檙e doing and find us to be an inspiration or a source of hope for their own communities.

In the book, you also talk about some of the challenges you faced in the beginning of getting Harlem Run off the ground, such as when male leaders and other run groups expected you to run your event plans by them before finalizing anything and making any decisions. Would you say experiences like that prepared you for some of the challenges you鈥檝e faced as a woman of color leading the charge on inclusivity in the running industry?

Absolutely. I wish I could say that a lot has changed, but the New York City running community remains a very male-dominated space. You鈥檇 like to think that other Black and Brown men will be in support of Black women, but we know that patriarchy is also a strong force. That鈥檚 why in this book, I try to be sure that I鈥檓 talking through an intersectional lens. What I found was that, as a Black woman, I was coming up against patriarchy and these men were looking out for each other and their own interests, and they were fine having a Black woman or another woman of color being second in command, or the one who鈥檚 doing the logistical support. And this idea of the frontrunner, the front-show person being a Black or Brown man was really hard for me.

So that鈥檚 what I just started focusing on, on creating my own space. I realized collaboration is what I would鈥檝e loved and I would鈥檝e loved the support of these folks, but I鈥檓 just going to build something that authentically feels good to me. But this is, once again, where everything about our existence is political. The running community, of course, has the influence of white supremacy, of patriarchy. I was coming up against those same issues that I would when I go into rooms, and I鈥檓 also one of the only Black people and the only Black woman in a room in this male-dominated space, recognizing that I鈥檝e been here before. This has always been my existence; it鈥檚 just a matter of context.

As someone who spent more than a decade working to qualify for Boston and who has actually never experienced the event in person, much of the chapter about your experience running the 2017 race was eye-opening and admittedly a little hard for me to read.

But at the same time, even before reading your book, I grappled with similar feelings when I was struggling with , and had moments when I had to ask myself 鈥淲hy exactly is this goal so important to me?鈥� I鈥檝e realized in recent years that a lot of it did come from being a minority in these spaces and how the majority of runners who pursue a Boston qualifier and eventually make it to Boston don鈥檛 look like me.聽

Having people express overt skepticism when I鈥檇 share this goal fed into all kinds of feelings of imposter syndrome as I pursued it, which is what motivated me to share my training and goal 鈥� I don鈥檛 want to just send the message that we as runners of color deserve to be here on the starting line. I wanted to show everyone, white people and BIPOC runners alike, that we鈥檙e capable and deserving of pursuing and achieving these lofty goals, too. How have your feelings and relationship with events like the Boston Marathon shifted over the years?

I appreciate you sharing that. Whether it鈥檚 the Boston Marathon or the Abbott World Majors, I鈥檓 always sitting here just thinking critically, 鈥淲ell, what is this goal about and what is the reason you鈥檙e pursuing it? What does this actually mean to you?鈥� I鈥檝e run some of them myself, and, yes, they鈥檙e amazing marathons. But the Abbott World Marathon Majors challenge was created, at least from my understanding, in order to create incentives around bringing people to these races and creating this hype, that completing the six of them was this monumental achievement.

Now, in my opinion, there are so many amazing races and marathons across the country that you could complete six of them and also feel that sense of accomplishment, right? So what is it about the World Marathon Majors? What is it about the Boston Marathon that you鈥檙e actually invested in and excited about? And when you start to think about that, if it鈥檚 just this idea that those particular six events mean something more than any other events, well, why? What is it that you鈥檙e chasing? And if the pinnacle of this sport that鈥檚 supposed to be for all people, is to get into this race that is extremely exclusive, whether you qualify or whether you fundraise sometimes $10,000, then there鈥檚 a real mismatch here in terms of what we鈥檙e saying running is about and what the pinnacle running experience is supposed to be or mean. And as you shared, there are obviously important reasons why people would see Boston or the Majors as meaningful for them. But I hope through what I say here in the book, whether you agree with me or not, you start to question why something is of value to you. And if the value comes from other people just saying, 鈥淗ey, this is valuable,鈥� then maybe you should rethink it.

After that first, not-great experience running Boston, you returned last spring for the 2022 race, this time collaborating with , which is known to be Boston鈥檚 first Black- and Brown-led running club, in holding pre-race events and spectating the race. What was the experience this year like in comparison? Was it somewhat of a full-circle moment to be there in such a different capacity?

Yes; I think what I was able to experience this year was what the Boston Marathon could be like, if Black and Brown people were centered and given space to be ourselves. So I credit that to PIONEERS Run Crew and the , who have really taken back this idea that Boston is only for a certain type of people and brought in just joy and our culture and our spirit. Part of that is , which is an unsanctioned marathon that takes place the day before the Boston Marathon and takes you through towns in Boston, such as Jamaica Plain and Roxbury, that are mostly Black, mostly immigrant communities. This challenges the idea that the Boston Marathon is actually a Boston Marathon, since it starts in the small town of Hopkinton and goes through mostly white suburbs before finishing in Boston itself. And believe it or not, I later found out that the police were called because our cheer station at 26.True was too loud and disruptive. Isn鈥檛 it literally the point of a cheer station to be loud and disruptive? But this man in this small, white town felt the need to protect his 鈥渟pace.鈥� This just emphasized the juxtaposition of the 26.True, like, 鈥淥K, that鈥檚 your version of the Boston Marathon. Well, we will show you the real Boston Marathon the day before.鈥� This isn鈥檛 just something that is happening in Boston; it鈥檚 happening all over the country. My message in that really, is it鈥檚 important and we, as Black people, are creating our own stuff. And we will continue to do that whether you get on board or not.

Will you be back in Boston for part of your book tour this spring?

It鈥檚 not on the schedule right now; I have not been invited in any particular way. I would love to be there because Kara Goucher, Des Linden, and Lauren Fleshman also have books coming out before the race, and I think this is the most books being published by women in running ever. So, if I could put that into the universe, I would love to see all of us on a panel together, talking about our books, all of which are critical of the industry.

You recently about meeting a woman during one of your book tour stops who shared that she never knew our national parks were once segregated. Did you expect to hear comments like that and was that why you chose to include the timeline of key moments in both American Black history and running history even though this book is largely a memoir of your own experiences?

Yes, absolutely. This woman also had no knowledge that there was a point where Black people could not go to public pools, that they shut down rather than let Black people swim there. That wasn鈥檛 her history; that was her upbringing and her experience. But these were contemporary laws, and for many white folks, it is that intentional erasure and miseducation that leads people to just live in isolation of anybody else鈥檚 experience.

The people in power are the ones who create the narrative, the histories and the stories that we learn and it鈥檚 by design that white people don鈥檛 know their own history. Slavery is as much, if not more white history than it is Black history because white people designed and perpetuated the system. So contextualizing what this world actually looked like during this period of running and what our experience as Black people was, was essential to help white people and all people really understand. I鈥檓 not just saying I felt this way; I鈥檓 actually showing the conditions that create the environment such that I would feel a lack of belonging, when that鈥檚 not what I want to feel. This is the society and industry and community that I inherited.

And in the book you also talk about the initial meetings with the Running Industry Diversity Coalition, before it was officially launched with you as co-chair, and how those meetings were particularly tense, to put it mildly. But you鈥檝e also talked about how you do your best to avoid goading white people into guilt and shame when it comes to carrying out RIDC鈥檚 mission, while also emphasizing that it鈥檚 important for white people to acknowledge the role they鈥檝e played in marginalizing minority groups. What would you say are some other key components in keeping these conversations going and getting brands and industry leaders to take real action toward inclusivity and racial justice?

Something that I鈥檝e become accustomed to doing is to show how I, as a Black woman, also have privilege, and that this is not something that is exclusive to white people. Often what happens when you talk to white people is that they say, 鈥淏ut I grew up in poverty,鈥� or 鈥淚鈥檓 an immigrant,鈥� Or 鈥淚鈥檓 a first-generation American and I鈥檝e struggled, too.鈥� But being white has never been a point of struggle for them.聽

I say this because I think it鈥檚 important to mirror and be instructional. And I say, 鈥淚鈥檓 a Black woman who is able-bodied. I鈥檓 a Black woman who is cisgender. I鈥檓 a Black woman who isn鈥檛 neurodivergent.鈥� All of those things gave me privilege to be able to write this book, to be able to show up in spaces and move my body. And so I also have to be a disability activist, I have to be championing trans and non-binary folks. It鈥檚 not just white people; each of us has our role. I hope that helps people see 鈥淥h, she doesn鈥檛 hate me. She鈥檚 talking about these systems that are set up to prioritize certain people and even she exists within it.鈥� It鈥檚 really a call to action to get on board like, 鈥淥h, you have only had this blissful experience while running. Guess what? I want that, too. Let鈥檚 work together.鈥�

You鈥檝e shared that you expect to get 鈥渉ate mail鈥� about some of the book鈥檚 chapters, but say that鈥檚 a good thing because it means people are talking. But do you typically engage with those people? How do you navigate figuring out where it can actually be productive, especially when you hear the same tired comments like, 鈥淪tick to running鈥� and 鈥渒eep politics out of running?鈥�

Honestly, it depends on where I鈥檓 at and how I鈥檓 feeling. Sometimes a comment lands for me in a way that I feel like I鈥檓 in the right frame of mind where I can answer it and don鈥檛 feel personally attacked. Other times, it is exhausting and I will not engage. But people who have genuine questions like, 鈥淚鈥檝e never seen the world that way. I can鈥檛 even understand. Can you explain it further?鈥� Folks who come from a place of curiosity, I am interested in engaging with because we have to remain curious. That鈥檚 really the only way that we build empathy and then we can make change. I think I have a good feeling at this point in my life to see when there鈥檚 a genuine conversation, and when somebody just wants to incite a feeling or troll me, and that will be my guide.

You鈥檝e also shouted out athletes like Alysia Monta帽o and Mirna Valerio for being unapologetically themselves in sharing their experiences and navigating the running world as Black athletes and how that has helped to validate your own experiences. Who are some other women in the running scene who you think are changing the game or have had a significant impact on your running journey?

, co-founder of (CSRD). The more I get to know her, the more I鈥檓 blown away by how honest, intentional and just brave she is. Also, , who is not somebody whose role is to talk about anti-racism. There should not be the expectation that every Black and Brown person is talking about racial equity. Does every Black and Brown person want equity? Of course. But our sole role on this Earth is not to talk about and try to deconstruct systems. For me, this is my passion and racial justice and equity is actually the work that I do. But India is a Black woman, this work isn鈥檛 what lights her up. She鈥檚 a coach who is the voice of a lot of races and does a lot of content focused on getting beginners into running, which is a beautiful thing. She is taking up space and showing her joyful, lived experience. Another one is , who served as one of the original leadership partners of RIDC and who I鈥檝e heard say, 鈥淚鈥檓 not a runner-runner.鈥� But she runs, she moves, and she is also somebody who鈥檚 always speaking unapologetically and has just done an incredible amount of good in the running industry.

You鈥檝e talked openly about how, as a Black woman, you鈥檝e always needed to be cognizant of your personal safety and just watch your back when you鈥檙e out for a run. The recent tragic murder of Eliza Fletcher re-bubbled up some of this discussion about how these cases usually don鈥檛 get as much attention when they involve women of color. You鈥檝e been asked before if women鈥檚 safety concerns affect you differently as a Black person, which has made you see how even womanhood is typically reserved for white people. How would you like to see the running industry improve when it comes to prioritizing and centering our safety and truly making this sport open to all?

Damn, good question. I mean, the murder of Eliza Fletcher absolutely was tragic and traumatic, but what it also showed me is that representation does in fact matter. Because when it鈥檚 a white woman who鈥檚 murdered, other white women and other white people feel like that could be them, so it matters to them. But when it鈥檚 a Black person, when it鈥檚 a Black woman or Black man, the response is not the same because they don鈥檛 relate to that story. And that鈥檚 where the problem is, that there is a sense of humanity and a sense of womanness or a sense of being centered, that is coupled with whiteness. Obviously, I don鈥檛 want anyone to be murdered while doing anything. But I want the same outrage, I want the same outpouring of support and demand for resources to come when our lives are taken. It鈥檚 even been reported that several months earlier, reporting that she had been attacked by Fletcher鈥檚 killer, but her account was not taken seriously. The way our lives are valued is not the same, which is why we say 鈥淏lack Lives Matter.鈥�

You鈥檙e juggling so much now between writing and now promoting this book and everything else you鈥檝e got going on in your career. The first thing you have listed in bios such as your LinkedIn headline is 鈥渄isruptor,鈥� which I think is awesome. Is that how you want to be known and remembered?

Yes, absolutely. I do a lot of things and that鈥檚 also just who I am. My nickname that my father gave me from a very young age, 鈥淧owdered Feet,鈥� speaks to that. I think that it鈥檚 really led by my curiosity of saying, 鈥淎re we doing this just because things have always been done this way? Is there a better way of doing this? Are we doing this and leaving people out?鈥� That doesn鈥檛 mean that I always have the answers or even the resources to address the system or the story or the place that I鈥檝e disrupted. It is powerful when somebody says something that causes you to pause and rethink the way you do something, rethink why you do the thing that you do. That鈥檚 what I hope my legacy is.

You recently held your first for women of color in the running industry. What was your vision for the event? Do you plan to make it an annual tradition?

Yes; we will absolutely be doing it next year. We say this is for women, femme and non-binary folks of color, and we had all of those people attend. But there were probably over 65 women of color who were there. And I was just looking around, 鈥淚 know there are more women of color in this industry, why aren鈥檛 they here?鈥� The goal for the retreat was, on one hand, simply just to provide a space where these folks could feel seen. We wanted to affirm, 鈥淵ou are not the only. Look at how many of us there are.鈥� We wanted to create networking opportunities, so that somebody who maybe is junior level could find mentorship and support that they may not have internally. Our goal for Year 2 is to be even more intentional with creating tracks for people who are entrepreneurs, as well as for people working for brands, retailers, and events. Our goal is to really shift the industry and ensure that more women, femme, and non-binary folks are in it and can see what it means to have a career in the industry.

How has your trajectory in your running journey and doing so much work in the industry impacted your identity as a runner? What have you learned about yourself both as a woman and as a runner?

As a runner, I鈥檝e learned that I really don鈥檛 care about accolades. Medals don鈥檛 matter to me. Particular races don鈥檛 matter to me. And maybe that鈥檚 because I鈥檝e been there, done that. That doesn鈥檛 mean that I won鈥檛 ever get excited about or train for a race. But running is just something that鈥檚 an important practice in my life and an important teacher in my life. And then as a human being, it鈥檚 taught me that you can really love something and also want to change it. Something can be transformational for you and still not be accessible for other people, and you can and should pursue that.聽

What other projects do you have going on in the coming months?