If It Ain’t Broke, Break It

Black Diamond has made a name for itself by dreaming up ways to abuse your gear well before you do. This fall the company releases its latest graduates from the class of suffer.

Back in the early 1990s, some engineers and quality-assurance specialists were standing inside Black Diamond’s Salt Lake City QA lab around a machine designed to rip apart things that you hope never actually rip apart—at least not when your life depends on them. Carabiners. Ice screws. Harnesses. This machine, an Instron 3300 tensile tester, can apply upwards of 18,000 pounds of tension, roughly the same as dangling three Toyota Tundras off whatever you put inside it. The reason you’d rip apart climbing gear is simple: make it fail, find its weaknesses, build it better.

Relatively speaking, most things fail pretty handily when faced with the awesome power of the Instron. Carabiners might pop at around 6,000 pounds. The wires in some of the smaller Camalots—removable cam devices that expand in cracks and anchor climbers to vertical rock walls—might go at half that, which is still a lot higher than anything a windmilling human might generate in the worst possible fall. On this particular day, however, the Instron had met its match. Up and up the power went: 10,000 pounds, 12,000 pounds, 14,000 pounds. The machine began to whine. Everyone took a step back.

Inside the machine, pinched between two vise-like clamps, was the most ridiculous-looking ice tool you’ve ever seen. The shaft was maybe six inches long, about the length of a pint glass, colored bright orange and made of extruded aluminum. Attached to one end was a pick and an adze, just like you’d expect, but at the other end, where you’d normally find a much longer shaft and a spike for puncturing hard snow, was another pick and adze. It was a double-headed ice ax—if you will, a dumbbell of complete impracticality.

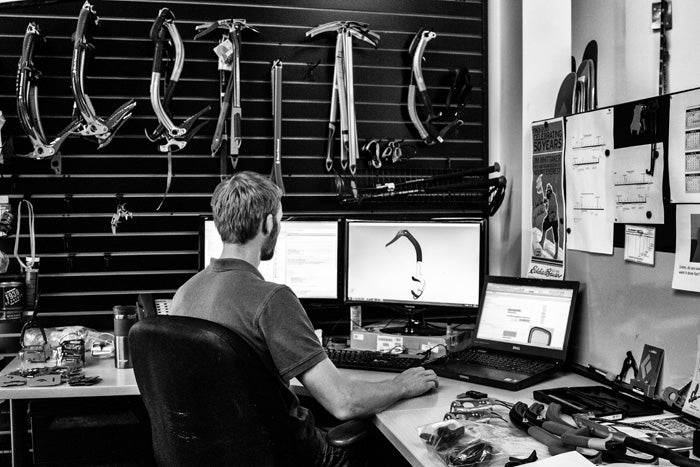

“The guys back there in quality assurance are Dr. Doom guys,” says Kolin Powick, who oversees Black Diamond’s climbing division. “They’re always thinking, How are people going to use our gear, how can they damage it, what’s going to fail? We can put five years of use on a piece of equipment in five hours.”

The men standing around the machine that day were not interested in wear and tear, and never in a million years would they try to sell such a silly tool. Rather, at issue was what Powick calls a “classified glue,” an adhesive so strong, you could probably use it to stick wings to airplanes. Designers wanted to use the glue to hold the head of an ice tool to the shaft in place of rivets, which require holes that weaken the materials. If the secret stuff was as strong as they hoped, it would open up new designs and new materials that would make Black Diamond’s ice tool the strongest by weight the climbing world had ever seen. It was a difficult question to answer, though, because the riveted spike on the standard tools kept failing before the glue on the head, so workers pieced together the two-headed version instead.

At a whopping 17,000 pounds of tension, the glue finally gave out. Even in the face of such enormous forces, there was no explosion of parts. Shrapnel did not pierce the room. “It was just the slightest pop,” shrugs Douglas Heinrich, VP of equipment and a former X Games ice climber. Yet that tiny snap would lead to the world’s first carbon-fiber ice ax, the Black Prophet. A later version, the Cobra, would one day hang in the Smithsonian as a testament to just how far ice axes have evolved.

[quote]“If we’re not willing to try things like that, then what are we doing?” Heinrich asks. “If we don’t, then we are just another consumer company, and that’s not where the magic is.”[/quote]

THAT EXPERIMENT lies at the heart of what has made Black Diamond one of the most respected outdoor-gear manufacturers on the planet, a company that has grown from a crude forge producing buck-fifty pitons in Yvon Chouinard’s California garage to a $200 million publicly traded juggernaut in the heart of some of the country’s most beautiful mountains. Few if any outdoor companies in its class have more engineers (32 out of 296 employees) or have spent more time and resources ripping, bashing, and tearing apart their own gear to discover what works and what doesn’t.

As a result, climbers and skiers around the world now have ice axes that fit on ski poles and powerful headlamps that weigh almost nothing. Backpacks embedded with something called JetForce Technology can inflate with 200-liter bladders to about seven times their size at the yank of a handle to help keep avalanche victims from being buried and suffocating beneath the snow. Look in the gear closet of any climber or backcountry skier and you’re almost guaranteed to find something that has survived a round in the Instron or some other torture device the company’s engineers have dreamed up.

As cool as the Black Prophet was, that was more than 20 years ago, and a lot of magic has happened since. People ski Everest. Two guys climbing two of Yosemite’s biggest walls in a day is no longer such a big deal when one guy, Alex Honnold, can climb three of them, alone and unroped, in the same amount of time. There is no doubt that the scientists at Black Diamond have played a crucial role in pushing those boundaries by building gear their friends can trust.

“Innovation happens in that space between where a sport is and where it’s going,” says Peter Metcalf, the company’s CEO. One day last summer, Metcalf sat in his office surrounded by old carabiner dies, the wood-shaft ice ax he used during a 1970 NOLS course, and a page torn from �����ԹϺ��� magazine that offered a less-refined reminder of what his company is all about: “Pain is temporary. Suck is forever.”

“There are a lot of branches that go nowhere in that space for innovation,” he adds. “The trick is to find the ones that do lead to great gear, but doing that requires people who are out there doing the sports.”

Like any company looking to improve the quality of its wares, Black Diamond has a robust team of professionals providing feedback. They are out there climbing gneiss walls in Greenland with new magnetic carabiners or skiing unexplored Antarctic peaks with prototypes of skis and skins that will one day make it to market. Yet, on any given day, the employees in Salt Lake City are themselves out roaring around the Wasatch with their own prototypes. Everyone here is a “user.” Designers are up at dawn, skiing backcountry runs like Scotties Bowl or Pink Pine, while the marketing guys might be picking their way up a sun-warmed crag that afternoon.

Feedback from users all over the world finds its way into an elaborate online system. If something isn’t working right, it’ll come up multiple times. Armed with that feedback, engineers and designers can get to work in the quality-assurance lab to try and re-create the failure, which sometimes means building unique machines to cripple the gear. Once they know exactly what’s happening, teams can fix it.

THIS FALL, Black Diamond expands its war against suck with a raft of new offerings that have all benefited from the “use, design, engineer, build, repeat” ethos that defines the company. All these items have been put through the wringer, though two stand out.

To be fair, one of these items isn’t a single item at all but rather a whole line of them. A few years ago, Black Diamond took the same engineering and testing methods it employs on its hardware and applied them to a set of men’s apparel. This fall the company will introduce a women’s technical line that is the result of years of fabric testing and statistical modeling and countless hours of both lab and field testing. To get the right fit, designers used full-body scans of more than 400,000 women and studied the data to tweak the garments’ dimensions for active, athletic builds. “It takes the emotion out of fit,” says Tara Latham, a designer. “This is true for everyone, like our CEO. He likes to think he’s a medium, but really he’s a small with big lats.”

The women’s ProShell and Active Shell outerwear collections include pieces like the Sharp End Shell, a Gore-Tex Pro jacket designed for hardcore expedition use. Others in the Windstopper Active line, like the Convergent Down Hoody, are meant for cold and tough, “done in a day” activities like a long ice climb or a big day of skiing. The Convergent is a windproof, highly water-resistant insulated jacket with a new synthetic-fiber-and-down blend from PrimaLoft that doesn’t wet out as fast and retains 95 percent of its insulating ability even when it does get soaked.

Coolest of all, most items in the line include simple but effective touches, most notably a new cinch-tab system developed by a small embedded-components company called Cohaesive that’s being launched in partnership with Black Diamond. The discreet system—a souped-up, drastically refined pull-tab setup—allows easy, one-handed microfit adjustments even with gloved hands and is the first non-Gore product that the notoriously protective W. L. Gore & Associates has allowed to be laminated directly into its waterproof-breathable membranes.

Other items, like the Induction Shell jacket, include fully taped Windstopper membranes and specially designed Swiss Schoeller fabrics that help blur the line between hard and soft shells. Gore has forbidden anyone from divulging exactly what a fully taped Windstopper membrane can withstand, but Black Diamond designers and engineers spent three days at Gore’s testing facilities in New Jersey, hosing down garments and collecting data, and the results are indeed impressive, especially if you’re ever caught in a horizontal downpour.

Of course, all these items have gone through the Instron and myriad other machines that tear, abrade, and wash fabrics in, say, salt water. Before the company would commit to the Cohaesive tabs, engineers at Black Diamond built a comical but highly effective four-arm robot that would pull the drawstring over and over, as many as 2,000 times, to see how it would wear out over its lifespan. “I can go over to the lab and say, ‘Hey, can you figure out a way to test this fabric or this part of a jacket?’ and they can do it,” says Lauren Deuser, a textile engineer. “They have such varied backgrounds. They’re like mad scientists.”

For the men, a new line of Gore and PrimaLoft technical wear comes out this fall, and next spring Black Diamond plans to release women’s crag wear. But soft goods aside, in the end it all comes full circle with the hardware. This winter, ice climbers will have a long-distant cousin of the Black Prophet in their hands, the Fuel.

Built on Black Diamond’s previous ice tool, the Fusion, which was designed to help elite climbers like Will Gadd win World Cup competitions, the Fuel is more of an everyman’s tool—lighter, easier to swing, and more forgiving all around. Engineers opened up the pick angle to help it sink better into ice, shortened the shaft a little, and shaved the weight to a respectable 638 grams. Instead of the Black Prophet’s carbon-fiber shaft, the Fuel uses hydroformed aluminum, the same stuff employed in high-performance road bikes and sports cars. It even has some of that special glue.

[quote]“You can dissect almost anything we make and see a story of BD at its best,” says Bill Belcourt, director of R&D, who led the Fuel’s development. “If you only feel alive when you’re outside pushing it, you only feel alive when you’re pushing it at the office, too.”[/quote]

Speaking frankly, Heinrich, the equipment VP and a former X Games ice climber, says ice tools like the Fuel are “halo” products, things that appeal to a passionate but highly specialized consumer. These are not the iPhones of the world (though Apple designers apparently keep Black Diamond products on hand for inspiration) but the deep-space life-support systems—the tools that drive exploration and allow a generation of climbers to push the limits of what can be done. But even a layman can hold the Fuel in his hands, marvel at its balance and precision, and feel the undeniable urge to sink it into something, even if it’s just the desk of the guy who envisioned it.

��