CHERRY

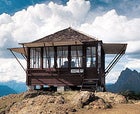

Poets on the Peaks: Gary Snyder, Phillip Whalen and Jack Kerouac in the Cascades, by Jon Suiter (Counterpoint Press, ) illuminates these beats’ little-documented time tending fire lookouts in the north Cascades—summer pockets of productive

Poets on the Peaks: Gary Snyder, Phillip Whalen and Jack Kerouac in the Cascades, by Jon Suiter (Counterpoint Press, ) illuminates these beats’ little-documented time tending fire lookouts in the north Cascades—summer pockets of productive

A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard

BY SARA WHEELER

(Random House, $27)

APSLEY CHERRY-GARRARD’S 1922 account of Robert Falcon Scott’s doomed South Pole expedition, The Worst Journey in the World, is one of the most haunting adventure tales of all time, but it’s hardly the whole story. In this first biography of Cherry (as his friends called him), Sara Wheeler—author of Terra Incognita, a brilliant exposition of her British countrymen’s infatuation with the cold continent—takes us through the expedition and beyond in this study of survivor guilt. Born into the landed gentry, 24-year-old Cherry sailed south on the Terra Nova in 1910, a paying volunteer accepted at the last minute despite his terrible eyesight. Nicknamed “Cheery Blackguard,” he remained sweetly optimistic in the face of privations and discomforts, writing in his diary, “I have never thought of anything as good as this life. The novelty, interest, colour, animal life and good fellowship go to make up an almost ideal picnic.” But the “worst journey”—the near-fatal trip in July 1911 that Cherry, Bill Wilson, and Birdie Bowers undertook to collect emperor-penguin eggs—damaged his health, and his discovery the next year of the bodies of Wilson and Bowers, his best friends, next to Scott’s, after their bid for the Pole, was a terrible blow, especially when he realized he’d been just a few miles away as they lay dying. Wheeler’s retelling of their famous ordeal is psychologically astute and deeply felt: “In Cherry’s bursting heart,” she writes describing him building his comrades’ burial cairn, “something died.” She teases apart the British sanctification of Scott, and the press hysteria that encouraged Cherry to blame himself, however irrationally, for his friends’ deaths. Considering the breakdowns he suffered upon his return, Cherry’s perseverance in producing his wry masterpiece of British understatement becomes an act of heroic determination. And in Wheeler’s hands, Cherry himself becomes, as she says of The Worst Journey, “a kind of parable,” reflecting “something universal: the eclipse of youth, and the realm of abandoned dreams and narrowing choices that is the future.”

—CAROLINE FRASER

GOULD’S BOOK OF FISH

A Novel in 12 Fish

BY RICHARD FLANAGAN

(Grove Press, $28)

HAVING GROWN UP in the literary poorhouse of Tasmania, novelist Richard Flanagan attempts an audacious bit of historical bootstrapping here—a sprawling, made-up classic of early Tazzy that, were it true, might have been the cornerstone of Australian letters. His imaginary author, William Buelow Gould, is an English convict sent to the notorious Sarah Island penal colony. There, his talent as a painter is noticed by the prison surgeon, who commissions him to record, in “scientifick” detail, the island’s exotic fish. Using a shark bone as a quill and specimens from a local fisherman as models, Gould becomes enchanted with the crested weedfish and sawtooth sharks he paints: “A fish is a slippery & three-dimensional monster that exists in all manner of curves, whose colouring & surfaces & translucent fins suggest the very reason & riddle of life.” Meanwhile he’s busily recording the Felliniesque details of life Down Under circa 1830, from the parson’s randy wife (“Ravish me!”) to the sadistic prison commandant. Although his fondness for literary tricks is too clever by half, Gould, er, Flanagan carries the book off with surefooted elan. Gould’s Book of Fish reads like an untamed relation of Tom Jones, set where the land was wild and its immigrants wilder.

—BRUCE BARCOTT

BREAKING CLEAN

BY JUDY BLUNT

(Knopf, $24)

MOVIE STARS DON’T keep glamour ranches in Montana’s Hi-Line country. The cold lonesome flatland is, 47-year-old first-time author Judy Blunt writes, “a country so harsh and wild and distant that it must grow its own replacements, as it grows its own food, or it will die.” Blunt was one of those replacements, raised on a cattle ranch so isolated that she had to move alone to the two-block “city” of Malta to attend high school. In this remarkably assured and moving memoir, Blunt chronicles the warts-and-all realities of modern ranch life: the anarchy of a one-room schoolhouse, the countywide panic of a prairie fire, the tyranny of in-laws living just down the road. Through it all simmers her growing indignation over the backward treatment of women on the farm, which finally boils over when her father sets her straight: Sons inherit the ranch, daughters don’t. “We girls would be left something of value,” Blunt writes, “but we should know at the outset that we would never inherit the land.” The most remarkable episode of Blunt’s story—when she divorces her rancher husband and raises three kids in Missoula while getting a college degree—gets short shrift, but perhaps she’s holding that material for a second book. We can only hope.

—B.B

FROM OUR PAGES

“I don’t climb mountains to prove blind people can do this or that,” writes Erik Weihenmayer. “I climb because it brings me great joy.” This month, the mountaineer recounts his successful Everest bid in the new afterword to TO TOUCH THE TOP OF THE WORLD (plume, $14), first excerpted in 国产吃瓜黑料 last December. In June, he will attempt to summit—and then ski—Russia’s Mount Elbrus.

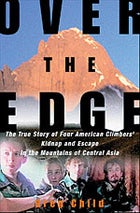

Also hitting bookstores this month is Greg Child’s OVER THE EDGE (Villard Books, $25), an account of the four American climbers kidnapped in Kyrgyzstan in August 2000. First reported in 国产吃瓜黑料 and now in development with Universal Pictures, Child’s story follows the hostages from their capture by Bin Laden—funded Islamic extremists to their risky midnight escape. He dismantles the claims of fraud that have dogged the climbers since one of their captors, last seen falling off a cliff, turned up alive weeks later. “This is the story of a story that refused to stop unfolding,” writes Child. Luckily he never tired of pursuing it.

And don’t miss frequent contributor Ian Frazier’s collection of piscine quests, THE FISH’S EYE: ESSAYS ABOUT ANGLING AND THE OUTDOORS (Farrar,Straus and Giroux, $22).