AT THE VENN intersection of people who read this magazine and people who had a good time today, you’ll find a lot of people who owe Thomas Meyerhoffer a thank-you.

Thomas Meyerhoffer

From left: Apple eMate; Scott Ms1 helmet; Smith Warp goggles

From left: Apple eMate; Scott Ms1 helmet; Smith Warp gogglesThomas Meyerhoffer

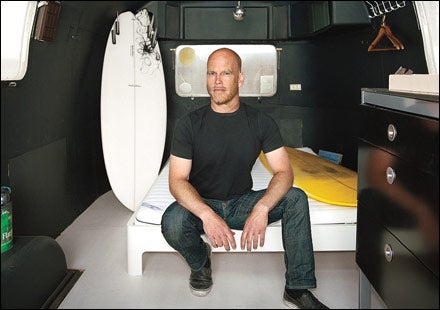

“It's about bringing an experience to the user,” Meyerhoffer says of his creations

“It's about bringing an experience to the user,” Meyerhoffer says of his creationsA dyed-in-the-wool California surfer who was born and raised in SwedenтАФcrazy but true; even the slow, steady meter of his Swedish accent sounds like Spicolian nonchalanceтАФMeyerhoffer, 42, is an award-winning industrial designer who has created or refined key pieces of equipment for surfing, snowboarding, skiing, motocross, and windsurfing. Companies from Nike to Black Diamond have sought his insight, mostly in the ten years since he left Apple, where he helped launch the design revolution that led to the iMac and saved that company in the nineties. And those are just the projects Meyerhoffer can tell you about. Many of his clients prefer to keep their partnerships secret, lest their competitors find out they’re looking to launch an ambitious new sports or technology product.

But Meyerhoffer doesn’t just help individual companies; he changes entire categories. Within any outdoor sport, a tradition of corporate inbreeding ensures that product advances are generally modest at best. A bike-frame designer may hop from bike company to bike company, but he probably won’t start designing alpine skis, which partly explains why it took manufacturers more than a century to abandon straight edges for sidecuts. Meyerhoffer, on the other hand, comes from a technology background and cites midcentury design giants like Charles Eames and Alvar Aalto as influences. When it comes to outdoor gear, he can think outside the box because he’s never been in it.

In 1994, he designed the first wraparound ski goggles, the Smith V3. At that point, goggles still resembled the boxy glasses from your high school shop class and offered little or no peripheral vision; wearing them meant racing downhill with blinders on. Meyerhoffer’s simple fix was to curve the lens around the temples. The V3 remains one of Smith’s all-time bestsellers.

When windsurfing manufacturer NeilPryde came to Meyerhoffer in 2002 with a request to revive its line of sails, he convinced the company to completely reformulate its construction process. Sail designers usually approached their work from a utilitarian standpoint, placing structural components as needed. Graphics were an afterthought. “You could create a high-performance sail that way,” explains NeilPryde product manager Robert Stroj, “but not one that also looked good.”

So Meyerhoffer did things backwards. He sketched out how he wanted the sails to lookтАФsleek and unclutteredтАФthen worked with Stroj to reengineer fundamental structures around his design scheme. The result was a product line so radically new in appearance that it landed NeilPryde on the cover of BusinessWeek’s Asian edition and earned Meyerhoffer a Gold Award from the Industrial Designers Society of America. “Within two to three years, everyone in the industry changed their sails to look like ours,” says NeilPryde marketing director Simon Narramore, who hired Meyerhoffer. “That’s the Thomas legacy.”

A year later, Meyerhoffer helped Flow reinvent the snowboard binding. To address riders’ main frustrationтАФthe need to sit down and fuss with tricky binding straps every time they got off a liftтАФthe company wanted a rear-entry system that offered as much control as a strap-in binding. Meyerhoffer’s design allowed the user to slide his foot into an adjustable front sleeve, then lean down and flip a lever to lock the back support into place. The entire procedure takes about two seconds.

“It’s about bringing an experience to the user,” Meyerhoffer says of his creations. “Sport product is not written about like art. It’s written about like, тАШThis gear is going to help you be this much faster.’ But becoming faster is not a measurable thing for most people. It’s how it feels. If you feel faster, you’ll have a great mountain-bike ride or a better surf. The user’s perception of the experience is what we try to deliver.”

ON A COOL, foggy late-spring day, I drive to Meyerhoffer’s house and design studio in Montara, a California beach town 20 miles south of San Francisco. The 2,900-square-foot space, a two-story modernist slab of glass and white concrete that he purchased in 1996, occupies a hillside lot one block above Highway 1. In the driveway rests a gutted Air┬нstream trailer Meyer┬нhoffer has been refurbishing for trips to his vacation home in Baja’s Scorpion Bay. The open garage shelters an immaculate silver 1965 Ford Cobra, two Scott mountain bikes, and a couple dozen surfboards.

“Obviously, California as a context changes things,” Meyerhoffer says when I ask how moving to the state altered the trajectory of his career. “But I was always outdoorsy. I had a lot of different interests. I wasn’t a specialist.”

With a shaved head and a short, neatly trimmed beard, he could model for the companies he works for, and he dresses with a rehearsed casualness that’s typical of those West Coast alphas who divide their days between playing at the beach and earning a lot of money. Born in Stockholm, Meyerhoffer attended art and design schools in London and Vevey, Switzerland. After a brief internship with Porsche in 1991тАУ92, he turned down their job offer to accept a position with IDEO, an international design behemoth based in the Bay Area. One of his first assignments there was the V3.

In 1996, he was plucked from IDEO by Jonathan Ive, Apple’s now-legendary design chief. There, Meyerhoffer led the team that created the eMate, a translucent laptop that many consider the precursor to the iMac. “For me, the most essential thing was that we broke the rules,” Meyerhoffer explains between sips of hot tea. “It was kind of a maverick move. Every single computer at that time was a beige box, and we made a very organic, translucent machine.”

By his own admission, Meyerhoffer works best in smaller, less structured settings, where he’s free to sketch ideas at midnight and go surfing at noon. So in 1998, he left Apple to branch out on his own. He didn’t intend to focus on the sports industryтАФhe still designs for a lot of technology firmsтАФbut Smith called, in hopes of replicating the success of the V3. At the time, helmets were becoming more common in snow sports, but no one had figured out a good way to integrate them with goggles. Meyerhoffer’s answer was the Warp, which had outrigger attachments that allowed the strap to fit around a helmet without pulling the goggles off the user’s face. The design became an industry standard, and outdoor firms have been calling ever since.

When Meyerhoffer takes on a new client, he establishes early on that he needs to be an integral part of their complete process. “I design the product, but I’m a component of their whole company,”?he explains. Rather than billing by the hour, as design firms commonly do, Meyerhoffer asks for fixed fees, company stock, or, better yet, royalties, which he believes keep both sides more involved.

He begins by working ideas out in pen or pencil. But his approach is more back-of-the-napkin than organized sketchbook. “All my sketches end up on one piece of paper,” he explains. “As a designer, you get trained to make nice sketches: тАШHere’s one idea. Here’s another.’ Obviously, I have to present like that to the client later on. But the way I design, the more scribbles, the better.”

And the more surfing, the better. Meyerhoffer and his two on-site employees (two others telecommute) take their daily breaks in the waves off Montara State Beach, just below his living-room window. He claims the sessions help him recognize and tune in to his creative impulses.

“Surfing is a great exercise that way,” he says. “If the wave’s not there, it’s not there. It’s made thousands of miles away. You have to sit in the water and wait for this little energy pulse to arrive. Then you have to be in the perfect position and paddle like crazy to get into the wave. And it’s a moment that will never come back. It just goes, and then it’s gone.”

THOUGH HE’S Swedish by birth, Meyerhoffer’s work doesn’t conform to assumptions about clean-lined Scandinavian design. From his goggles to the ChumbyтАФa softball-size Web browser in a beanbag, which Meyerhoffer crafted as “the anti-iPod”тАФhis designs share a sensibility that has nothing in common with Ikea-informed concepts of clinically austere shapes and spaces. “Scandinavian design today is completely square and boring,” he says. “It just uses a formula to call itself modern, but it doesn’t do anything. The world could definitely live without those products.”

His hourglass-shaped “art boards”тАФa personal surfboard project he’s been working on since 2005тАФlook like something from a Dr. Seuss book. One of them hung for eight months at New York’s Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum. Meyerhoffer says the boards were intended to get people to stop focusing so much on performance and just enjoy themselves. This same philosophy applies to his recent smartphone for Openmoko, an open-source cellular company creating devices that allow users to switch freely between carriers. “It has this completely weird, asymmetrical shape,” he says. “A lot of that is coming from my art boards. We’re trying to design a product that talks about what the company is offeringтАФnot to have to be a slave under your cellular provider.”

The project that has Meyerhoffer most excited right now is an ambitious plan to launch his own product line in the surf world. He’s sworn me to secrecy regarding the details, but I will say that surfing has never seen anything like it. His vision is so radical, it will either change the way people approach the sport or not catch on at all.

Meyerhoffer’s board-shaping shed sits just behind his garage. The dusty space is decidedly low-tech, with surf posters hanging on bare plywood and foam surfboard “blanks” resting on sawhorses. It’s in sharp contrast with the wire-frame CAD models on the 20-inch iMac in his white-walled studio. “Shaping boards has made me really focus and appreciate the beauty of developing products more hands-on,” he says.

I ask Meyerhoffer how, ultimately, he judges the success of his designs.

“How do you measure that?” he replies. “In sales? For a big company, it might be. But maybe it should be whether people love it and really use it.”

Or, as he puts it to me later, “in the end, the experience is what matters.”