Human existence is a process of constant refinement. Ten thousand years ago we gnawed at charred meat while squatting around a campfire; today you eat your prime rib amid luxury appointments in a keto-friendly restaurant. The first TVs were grainy black-and-white affairs, whereas now you can buy a stunning full-color display the size of your living room wall for a few hundred bucks at your favorite big-box store. Underpants are generally more comfortable. And so forth.

Bicycles also undergo constant refinement, especially when it comes to their drivetrains and gearing systems. The first bikes were ŌĆōthey had no gears at all, just a direct drive with a ratio determined by the wheelŌĆÖs diameter, hence their zany appearance. Then came chain drives that let you use equal-sized wheels, and freewheels that allowed you to coast, and derailleurs that allowed you to change gears. Today, you can shift seamlessly and effortlessly across a whole range of gear ratios with the push of a button. Unless, of course, your battery runs out, in which case your bike will revert to a singlespeed and send you back in time by 85 years.

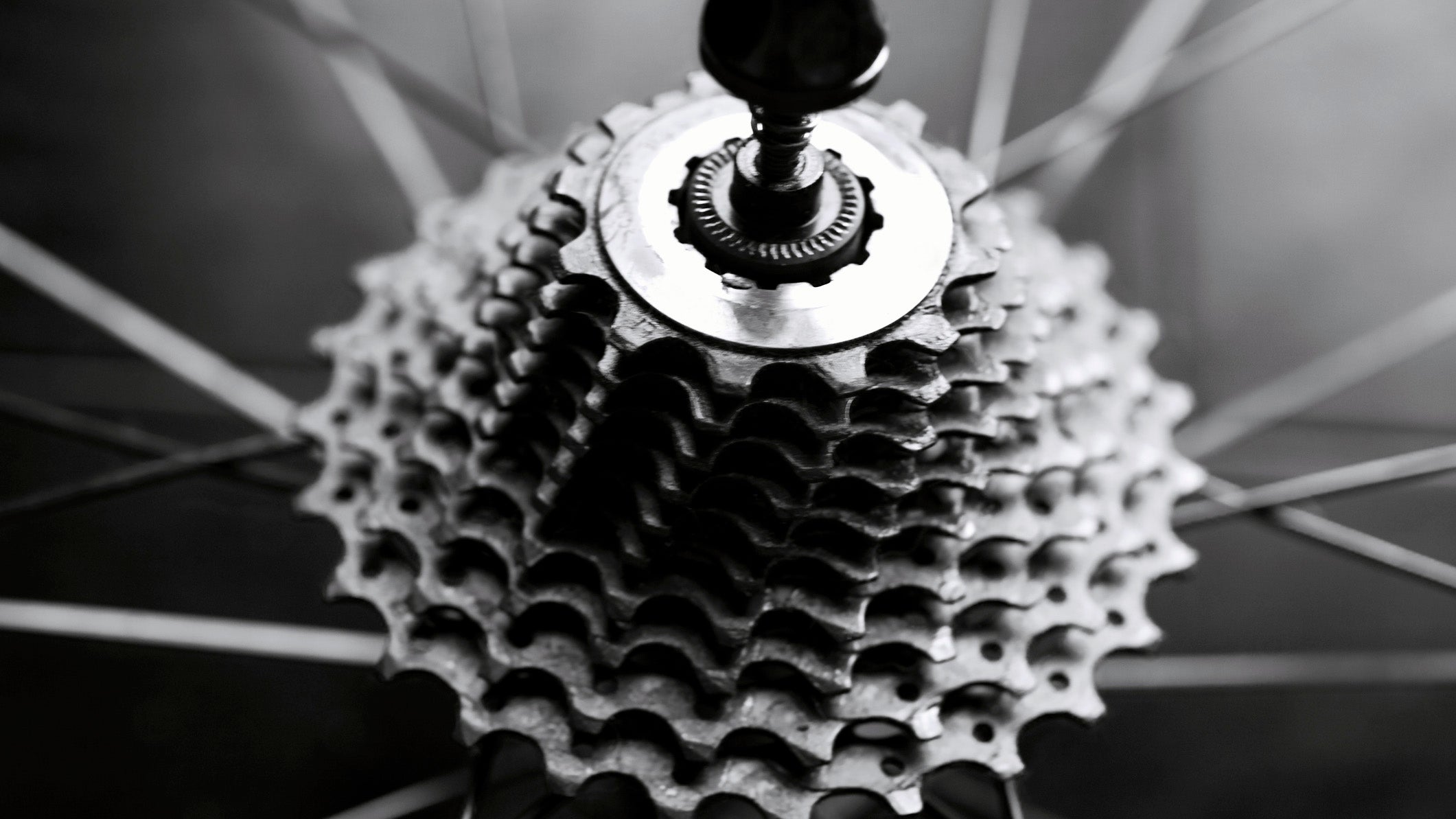

Electronic shifting notwithstanding, over the last several decades the biggest refinement in performance-oriented bikes hasnŌĆÖt been in the mechanics of shifting gears; rather, itŌĆÖs in the gearing range itself. A derailleur drivetrain from the midŌĆōto-late 20th century functions more or less the same way it does today. Sure, the shifters are usually integrated into your brake levers rather than on your downtube, but regardless of where the actuator is located, the system is doing the same thing. Much more significant is that, say, a mid-range Trek road bike from the late ŌĆÖ80s (I know because I have one) offered a 52/42 chainring with a 7-speed 13-24 rear cluster, which was fairly low and ŌĆ£novice-friendlyŌĆØ road gearing at the time. Meanwhile, its modern equivalent, a Trek Emonda ALR 5, comes with a 50/34 chainring and an 11-speed, 11-30 cassette. ThatŌĆÖs a slight four percent decrease on the high end, and a whopping 35 percent decrease on the low endŌĆōplus four more cogs in between, of course.

To be sure, lower gearing is a good thing for cyclists, especially newer ones. Why shouldnŌĆÖt you have lower gears for the climbs? Why stand and strain when you can sit and spin? Once upon a time you would have paid a price in both weight and shift feel to have what is essentially mountain bike gearing on a road bike, but thanks to all that drivetrain refinement this is no longer the case. Moreover, now that many of the compromises that come along with low gearing have disappeared, so has the stigma. It used to be considered ŌĆ£PROŌĆØ to sport giant chainrings and a cassette like a corncob.╠² Then came Lance Armstrong and his high-cadence climbing technique, which at the time seemed revolutionary, but in retrospect was probably just another smokescreen to distract from all the doping. Next it was compact cranksets, then the gravel craze. Now thereŌĆÖs been a total gearing inversion, and that ultra-low gear on your bike broadcasts to others not that youŌĆÖre some kind of wimpy noob, but rather than you eat steep climbs for breakfast.

Climbing on a bicycle is almost as psychological as it is physical. Certainly strength and fitness are the ultimate arbiters, but your determination to make it to the top and your willingness to endure discomfort along the way are tremendously important, and are at least as valuable as a few extra teeth on your rear cassette.

Still, while todayŌĆÖs drivetrains represent a net gain for the average consumer, we do forfeit a certain amount of simplicity in the move to more and wider gears, just as we do with any advancement. Climbing on a bicycle is almost as psychological as it is physical. Certainly strength and fitness are the ultimate arbiters, but your determination to make it to the top and your willingness to endure discomfort along the way are tremendously important, and are at least as valuable as a few extra teeth on your rear cassette. In fact, a surfeit of low gears can even act to undermine your morale. Your gears are like you bank account: when things get really tough your first impulse is often to plunder it.╠²If the gears are there youŌĆÖre gonna use them, even if doing so brings you to a virtual standstill. YouŌĆÖd probably downshift infinitely if your drivetrain allowed it, never arriving anywhere and existing forever on the same slope in a cursed manifestation of .╠²

However, as the paycheck-to-paycheck set knows all too well, scarcity breeds resourcefulness. No matter how ŌĆ£overgearedŌĆØ you are, once you reach that innermost cog and hit that limit stop on the derailleur, you know the rest is up to you, and if youŌĆÖre aware of this when you start your ride in the first place, you adjust your riding style accordingly. You donŌĆÖt mosey up to the foot of the climb, confident you can squander that assortment of CD-sized cogs in the back; rather, you approach it at tempo, making full use of your momentum to carry you up as far as it can before you start downshifting. You also use your body, getting in and out of the saddle, finding a rhythm, using the bars for leverage, and paying close attention to line choice and the road surface in order to take advantage of anything that might mitigate the incline or shorten the distance to the top. Anybody who rides a singlespeed mountain bike knows that they can actually be better for climbing, in that downshifting too much on a technical climb can make you lose almost all inertia and cause you to put a foot down, whereas on a singlespeed you come in hot, and often clean rocky sections more smoothly.

Still, while todayŌĆÖs drivetrains represent a net gain for the average consumer, we do forfeit a certain amount of simplicity in the move to more and wider gears, just as we do with any advancement.

ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs all well and good if youŌĆÖre young and fit,ŌĆØ you may be thinking. ŌĆ£But what about those who are older and have trouble distinguishing between creaky bottom brackets and creaky knees?ŌĆØ As someone in the latter camp IŌĆÖve been gradually gearing down over the years in deference to both age and fashion. However, IŌĆÖve also been dabbling in vintage road bikes, and I still enjoy them tremendously despite their tall gearing for all the reasons I described. Plus, itŌĆÖs oddly liberating: it reminds me that a road bike is essentially a racing bike, and that itŌĆÖs lots of fun to ride racing bikes, but if I donŌĆÖt feel like racing my bike that day IŌĆÖll just ride something else that not only has lower gearing but also dispenses with the drop bars and clipless pedals and narrow tires and all the rest of it. If youŌĆÖre always looking to downshift, sometimes what youŌĆÖre looking for is more than just another gear; sometimes it means you need a completely different type of bike.

ItŌĆÖs human nature to grumble about stuff that makes life easier, especially if youŌĆÖre a crotchety cyclist. Henri Degrange, father of the Tour de France, . ŌĆ£IsnŌĆÖt it better to triumph by the strength of your muscles than by the artifice of a derailer? We are getting soft; as for me, give me a fixed gear!,ŌĆØ he famously declared. In retrospect this is almost comically recalcitrant, so none of this is even to remotely suggest that bikes shouldnŌĆÖt have low gears, or that the increasing pervasiveness of them on bikes of all types means that weŌĆÖre growing weaker and ever-more coddled and that we should return to a time in which if you were a total wuss if you wanted to climb at a cadence of more than two RPMs. But it is to say that, just as rim brakes and friction shifters and quill stems and all manner of ŌĆ£obsoleteŌĆØ components still have their place in the cycling firmament, and can still confer benefits upon the rider, so too does a drivetrain that requires you to pick a gear and stick with it. It can be enlightening to reconnect with simplicity once in awhile, if only to remind yourself of whatŌĆÖs truly possible on a bike, and how much more important you are than the machine.

No matter how many gears you have, gravity is gravity. At a certain point downshifting is merely delaying the inevitable.