“ARE YOU READY?” asks Dr. Rohlen.

Illustration

“The Pain Lab is either a sort of brilliant skunk works or the new leader in barbaric testing.”

“The Pain Lab is either a sort of brilliant skunk works or the new leader in barbaric testing.”“No problem,” I boast. “I've skinny-dipped in the Arctic Ocean.”

Next to me is a square bucket bubbling with 32-degree water, ice cubes bouncing on the surface, a fish-tank aerator circulating the mix. Dr. Brooks Rohlen, a fit 38-year-old resident at Stanford University's Human Pain Research Laboratory, reaches for a stopwatch. Martha Tingle shifts the bucket a little closer. A tall, shy 52-year-old with cappuccino skin, she's a registered nurse and the lab's manager. Its founder, slender Swiss anesthesiologist Martin Angst, dressed in a black T-shirt and dark jeans, looks on quietly, as he will most of the day.

“Place your palm on the bottom of the tub,” Dr. Rohlen says, smiling a little too brightly for someone about to dunk my hand into a vat of ice water. “Keep your hand there until it is no longer tolerable.” His teeth glow as white as his lab coat; his hobbies, coaching the Squaw Valley freestyle-skiing team and running a charity that helps people establish memorial funds, would be full-time jobs for most people; and his boundless energy scored him a $40,000 research award on top of his anesthesiology residency. He's driven, kind, and funny, though sometimes it's difficult to tell which. Before I arrived at the Pain Lab, he said (and I quote), “We'll have you wetting your pants and calling your mom, but we'll send you home with a free sweatshirt.”

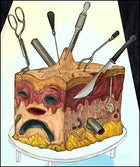

Looking around, I'm beginning to wonder if he wasn't joking. The Pain Lab lies in the far northwestern corner of Stanford's sprawling Palo Alto, California, campus, tucked away on the lonely fourth floor of the medical center. Every surface has been scrubbed, scoured, and disinfected; all olfactory evidence of the living has been erased. No windows allow anyone to look out or observe the goings-on behind the heavy locked door. I'm sprawled out on the lab's single full-length chair, spotlighted under two enormous reflector lamps. Laptops perch at each armrest, connected to a network of tubes and wires of indeterminate function. Nearby are racks of needles, rolling metal carts holding a ten-barrel Saalmann Multitester for creating sunburns, and a perfusion pump, which can inject subjects with enough narcotics in ten seconds to stop their breathing. There's a black gun safe full of drugs and, behind the chair, an honest-to-God shock-therapy machine that Dr. Rohlen assures me is used chiefly by a Russian associate named Vladimir. The Pain Lab is clearly either a sort of brilliant skunk works or the new leader in barbaric testing.

The ice bath is designed to determine the most important measure: my pain tolerance, or how much nerve-ending overstimulation I can endure. I assume I'm tough as toenails. I've swum beside ice floes, slept in snow caves, skied through frostbite, and scaled a snowy 15,000-foot pass with plastic bags on my feet (long story). I'm no Delta Force candidate, but I'm pretty confident I'm not constitutionally a sissy.

At Dr. Rohlen's nod, I plunge my hand into the water. At first, I feel nothing; then, after a few seconds, X-Acto knives begin lightly slicing the tendons of my wrist, scoring deeper and more sharply the higher they cut, and my cuticles and joints begin to throb. Then a thousand pins prick the back of my hand as all the discomfort crescendos. I fling my hand out.

“Oooooh,” I groan.

Surely minutes have passed. Rohlen looks at his watch. I lasted precisely 11.49 seconds (as ex-girlfriends will confirm). Relative to most test subjects, I came up grossly short: eight seconds under the average.

I'm not sure why I stomached so little. Maybe it was because I freaked out and thought the bath was full of hydrochloric acid. Maybe it was because as soon as Nurse Tingle grazed my wrist I wanted to blurt, “It hurts! Everything hurts.” Or maybe it was because of one of the main scientific mysteries the lab is unpacking: why one person's agony is a far cry from another's.

“Not even close,” Dr. Rohlen declares, noting that some people keep their hand plunged for up to a minute. Translation: “You're a pantywaist.”

THE GOAL of the Pain Lab is not to separate the men from the boys, of course. Nor is it to generate endless laughs at the names of the founder, Dr. Angst, and one of the first assistants he hired after creating the lab 12 years ago, Nurse Tingle. This is research, people!

Dr. Angst, 47, originally came to Stanford in 1994 as a visiting research fellow from University Hospital of Berne, in Switzerland, to study pharmacology. At the time, reliable tests hadn't yet been devised to measure the effectiveness of pain meds, his original focus. So he started the lab with the goal of generating precise findings about the nature of hurt. What makes it one of the world's premier research facilities is that the primary team of Angst, Rohlen, and Tingle, along with their half-dozen collaborators, have the ethical leeway to conduct red-hot, bleeding-edge “adrenergic receptor studies”鈥攂asically cooking, freezing, poking, shocking, and sunburning legions of volunteers in tests too difficult or expensive to conduct as full-blown clinical trials. (They do not, however, have the leeway to study, say, what went through Aron Ralston's mind when he sawed through his arm with the dull blade of a Leatherman knockoff. “That's out of my field,” says Dr. Angst. “Ethically, I can't take a sledgehammer to your foot.” Which is nice.)

Since its creation, the Pain Lab has provided strong evidence for some surprising theories. For example: Taking painkillers like Vicodin for more than a month makes a person more sensitive to pain (as if recovering from ACL surgery wasn't difficult enough), and people suffering from depression experience more pain (no wonder poets don't compete in the X Games). Currently, the Pain Labbers are trying to identify proteins in the body associated with pain, and they're also examining how low-voltage “transcranial electrical stimulation” (read: “juice to the noodle”) affects cognitive performance and postoperative recovery. (That's anesthesiologist Vladimir Nekhendzy's domain.) The most expansive of these is the test I'm mock-participating in, a study of 180 pairs of twins that's exploring whether pain sensitivity is determined by the genome. If this proves the case, curing hypersensitivity and chronic pain could be as simple as deleting a gene. But the results are still four to six years off. In the meantime, we're left to sort out on our own the likelihood that we were born soft.

I figured that, after a few days in Dr. Feelbad's lab, I might come home with data showing I work through pain like a Mack truck through toilet paper. But there was always another unsettling possibility: I'd inherited the wimp gene.

IF PAIN TOLERANCE varies wildly, our pain threshold, the first point at which we experience discomfort, is surprisingly uniform. In my first lab test, Dr. Rohlen placed a small black paddle on the tender skin of my inner forearm and connected it to two tubes circulating water from a bluish device wired to an IBM ThinkPad. The nickel-sized paddle heated incrementally from 35 to 52 degrees Celsius (95 to 125.6 degrees Fahrenheit), and my job was to click a computer mouse when the sensation turned from pretty warm to “That freaks me out a bit.” Easy enough.

“Five seconds,” Dr. Rohlen announced. “Heating!”

I chuckled to myself. Then I felt the heat. It swelled from warm to itchy to tingling. At the tipping point it turned to a sting, like icy feet in the hot tub, and I clicked. We repeated the test dozens of times, and my body pinpointed its threshold at 117.5 degrees, give or take a degree and a half.

This temperature is common, it turns out. Humans seem genetically programmed to recognize 117 degrees as an important warning point. Much higher, and skin will burn. But how much burn (or freeze, or pressure) you can accept seems to be significantly affected by past experiences. The lab has found that people who've experienced significant amounts of pain鈥攕ay, soldiers, athletes, or women who've given birth鈥攖end to have much higher tolerances, some of them capable of distinguishing up to 11 intensities of pain.

What this means is that (1) the easiest way to recover from a fractured arm is to have already broken your back. Relatively speaking, you feel fine. (2) Most people probably can't even imagine what it's like to lose a leg; the pain is off their charts. And (3) Lance wasn't lying when he said he could pedal harder: The tearing in his quads was nothing compared with the slow, devouring pain of chemo. At Indiana University's Simon Cancer Center, Armstrong had been forced to radically recalibrate his pain tolerance, so three years later, even if he was hurting as badly as other riders, he knew he could withstand more.

“He was contextualizing the pain,” Dr. Rohlen explains. Indeed, Rohlen himself has done it. As a competitive mogul skier, he didn't understand the true depth of pain until years of bumps led him to the OR for lower-back surgery. “That was the kind of pain that made me sweat, that made breathing hurt, that made walking impossible,” he says. “Now, as a physician, I see people in pain and I respect the truth in their hurt.”

All of which is fine for Rohlen, but the worst accident in my grand parade of mishaps was splitting my chin open on the monkey bars when I was 11. On the toughness scale, this puts me just ahead of Miss Teen USA and well behind rodeo clowns. And I'm not about to leap off a speeding train to “contextualize” future pain.

BASELINE TESTING continues this morning. This is good, I think鈥攁nother chance to redeem myself. Electrodes always signal pain ahead.

Dr. Angst presides while Nurse Tingle shaves my chest. Predictably, Angst is incredibly intelligent, extremely nice, and as thorough as a watchmaker on Ritalin. A highly respected doctor, he speaks in multisyllabic tongue twisters and would never say, oh, I don't know, “That patient has burning nipples and I have no idea why,” when he could say, “That patient has idiopathic areolar dysesthesias.”

Dr. Rohlen attaches a small electrode over my heart so that the PeriFlux System 5000, whatever that is, can measure CO2 concentrations in my skin, while Nurse Tingle plays Bach's Goldberg Variations to lull my heartbeat into its true resting state. Then Angst begins a tedious sequence of questionnaires: a demographic assessment, a Beck Depression Inventory, a Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. One question on the Profile of Mood States asks how “listless” I feel right now, and I'm forced to admit, “somewhat.”

“What do these have to do with anything?” I ask.

Dr. Angst shifts in his penny loafers. Twenty-five years ago, he says, we believed that our response to pain was hardwired. Stimulation caused nerve cells in the skin to come alive and tiny doors in them to open, allowing positively charged sodium ions to rush inside. The signal traveled nerve to nerve, up the spine, and into the brain, where our CPUs processed it as “an uncomfortable experience that causes anxiety.”

“Now we know that pain is felt through a web of systems that is enormously complex,” Dr. Angst says. “And it works top to bottom and bottom to top.”

Prime examples of this are the familiar placebo effect and the current hot topic in pain, the “nocebo effect.” The placebo effect, which can last days, says that if you expect to hurt less, then you will. The brain sends out endorphins, essentially small doses of self-manufactured morphine, to receptors in the central nervous system. Then, when this weakened pain signal makes it back to the brain, the endorphins in which your gray matter is marinating produce a sense of well-being or mild euphoria (think: runner's high). Visualizing successful post-op recovery or even psyching yourself up before a triathlon is not just a mind game. You're optimizing your whole body to feel less pain.

Conversely, with the nocebo effect, nervousness has been shown to heighten pain sensitivity by as much as 45 percent. “Dios mio!” leads to a release of cholecystokinin, a polypeptide only recently found to exist in the brain that amplifies and heightens pain perception.

“It's the bad guy,” Angst explains. “The placebo effect is Spider-Man, and the nocebo effect is…the bad guy.”

Nice try, Dr. Angst.

“If you're really anxious about falling off your mountain bike,” Rohlen says, “then that anxiety is gonna make falling hurt more than it would have.”

This is it, the source of all my power: moronic optimism! “This bike saddle fits like a La-Z-Boy!” “Sure I'll test the landing, those are just pillows of snow; no, the pillows of snow weren't rocks!” “Of course you can inner-tube Class IV.”

But as far as my pain genes are concerned? The answer comes outside the lab.

DAWGS & DINNER is a monthly gathering where Pain Labbers and their friends and dogs get together to decompress. Tonight, Nurse Tingle hosts from her homey fifties ranch house in Half Moon Bay, grilling sausages (Dawgs & Dawgs) while a mutt and a bulldog race laps from the living room out to the fire pit and back. Here, leaning across the tile bar for a piece of blue cheese, I meet Jacques Rattaire, a 47-year-old French waiter and exercise nut (racquetball, 24 Hour Fitness) with the square shoulders and flat chest of an oversized Lego man. Rattaire is a close friend of Dr. Rohlen and the Lab's star volunteer.

“So they shocked you?” I ask again, just to make perfectly clear I've heard him right. “Twice? On the temples? Forty minutes each time?”

“Yes.”

“And what did it feel like?”

“Very nice, very painful.”

“Seriously? What exactly did it feel like?”

“It felt like a frying pan sizzling on my forehead.” Jacques sets his red wine down so he can demonstrate, pressing hard on his hairline.

“And what happened?”

“Oh, he was grumpy like an old man,” Jacques's girlfriend pipes in.

“Yes,” he agrees. “I had a short fuse. Not for long. A couple days.”

“Why did you do it?” I ask, trying not to betray that I think this is borderline insane.

“I'm a little bit of a daredevil,” he says like a perfectly blas茅 Frenchman.

The group drifts off into the dark, toward the fire pit, and I'm left alone at the cheese counter, thinking. Objectively speaking, I know that this transcranial-electrical-stimulation business is safe. But, still, in the way that some people have an irrational fear of clowns, I have a very strong fear of unnecessary voltage. If there's a bit of crazy in true tough, I figure, then give me my free sweatshirt and I'll keep the genes I got.