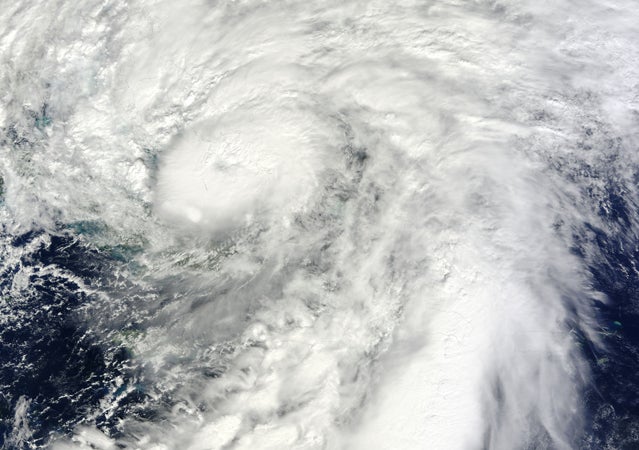

It was a bad week. Hurricane Sandy struck New York with great force, destroying thousands of people’s homes, killing dozens, and bringing our nation’s greatest metropolis to a halt. As of this weekend, half the city is still without power, everything is wet, and, as a special bonus, New Yorkers will now be inundated by a (on the plus side, there were no tourists in Times Square for five minutes).

When disaster strikes a place like New York, a city of transients, the effect is far reaching. The flooding of the Greatest City on Earth is global news. It transcends that place. As pictures of crumbling sea walls and violent storm surges disseminated, worried parents, brothers, and sisters around the world, from New Zealand, to Pakistan, to Kansas, picked up the phone and called their loved ones.

But even those that suffered loss can take solace in knowing that this disaster will not, like so many others, be meaningless. If there’s an upside to such a high-profile disaster, it’s that it forces change. In this case it’s the realization, in circles where power resides, that the Earth is changing, and that it probably has something to do with us.

New York’s own mayor, Michael Bloomberg, announced on Thursday that he is endorsing Barack Obama for a second term as a direct result of Hurricane Sandy. “The devastation that Hurricane Sandy brought to New York City and much of the Northeast,” he begins, “…brought the stakes of Tuesday’s presidential election into sharp relief.” The endorsement may seem like an obvious attempt to show his concern to the citizens of New York, but for Bloomberg, a noted political independent and capitalist suspected of having larger aspirations of office, it represents a serious political risk on his part. Perhaps he simply foresees a future where people are voting with their planet instead of their tax returns. Or just maybe, he sees this not as a political issue, but one of survival.

Anyway, without further depressing reflection, here’s your Weekend Reading!

Climate change is becoming increasingly hard to ignore in a world filled with overwhelming scientific and statistical evidence. So why can’t politicians talk about it? .

“Mitt Romney has gone from being a supporter years ago of clean energy and emission caps to, more recently, a climate agnostic. On August 30, he belittled his opponent’s vow to arrest climate change, made during the 2008 presidential campaign. ‘President Obama promised to begin to slow the rise of the oceans and heal the planet,’ Romney told the Republican National Convention in storm-tossed Tampa. ‘My promise is to help you and your family.’ Two months later, in the wake of Sandy, submerged families in New Jersey and New York urgently needed some help dealing with that rising-ocean stuff. Obama and his strategists clearly decided that in a tight race during fragile economic times, he should compete with Romney by promising to mine more coal and drill more oil. On the campaign trail, when Obama refers to the environment, he does so only in the context of spurring ‘green jobs.’”

Celebrate the return of basketball with an extensive oral history of the 1992 Olympic Men’s Basketball Team. .

“It was always a silly rule. According to international basketball guidelines in place for decades, professionals from leagues all over the world could compete for their countries at the Olympics—but NBA players could not. The effect was to balance out America’s towering advantage in the sport. You know, give the poor bastards a chance. The rule was dropped in April 1989, though, after the United States finished a humiliating third at the previous summer’s Olympics in Seoul. Parity, everyone learned, wasn’t nearly as captivating as dominance. And make no mistake: Dominating was as important as winning. The idea was to dazzle, to put on a display of American might so awe-inspiring that the best our rivals could hope for was a silver medal. Or even better, Michael Jordan’s autograph.”

The Information Age is destroying what it means to go somewhere you’ve never been before. A meditation on the importance of being in the moment. .

“I get off a 15-hour flight from North America and turn on my BlackBerry at some Asian airport. Instead of focusing on the immediate environment and the ride into town, I am engrossed in the several dozen emails that piled up while I was en route, a third of which require a serious response, and one or two of which relay worrying news. As if that isn’t enough of a distraction: throughout all my journeys, because of the 12-hour time difference, each morning in Asia begins with a slew of emails from the East Coast, again requiring responses, again relaying crises to deal with. Wherever we are, we are all always available, and everybody knows it. The media tell us how lucky we are to live in the Information Age. I believe we have created a hell on Earth for ourselves.”

A Canadian archaeologist suspects we may have missed an entire chapter of history: the meeting of Native Americans and the Vikings. .

“One day in 1999 Sutherland, an Arctic archaeologist at the museum, slipped the strands under a microscope and saw that someone had spun the short hairs into soft yarn. The prehistoric people of Baffin Island, however, were neither spinners nor weavers; they stitched their clothing from skins and furs. So where could this spun yarn have come from? Sutherland had an inkling. Years earlier, while helping to excavate a Viking farmhouse in Greenland, she had seen colleagues dig bits of similar yarn from the floor of a weaving room. She promptly got on the phone to an archaeologist in Denmark. Weeks later an expert on Viking textiles informed her that the Canadian strands were dead ringers for yarn made by Norse women in Greenland. ‘That stopped me in my tracks,’ Sutherland recalls. The discovery raised tantalizing questions that came to haunt Sutherland and drive more than a decade of dogged scientific sleuthing. Had a Norse party landed on the remote Baffin Island coast and made friendly contact with its native hunters? Did the yarn represent a key to a long lost chapter of New World history?”

Entrepreneur and privatized space travel pioneer Elon Musk sits down with Wired for an exhaustive interview on his plan to get us to Mars within his lifetime. .

“Since 1989, when a study estimated that a manned mission would cost $500 billion, the subject has been toxic. Politicians didn’t want a high-priced federal program like that to be used as a political weapon against them…. So I started with a crazy idea to spur the national will. I called it the Mars Oasis missions. The idea was to send a small greenhouse to the surface of Mars, packed with dehydrated nutrient gel that could be hydrated on landing. You’d wind up with this great photograph of green plants and red background—the first life on Mars, as far as we know, and the farthest that life’s ever traveled. It would be a great money shot, plus you’d get a lot of engineering data about what it takes to maintain a little greenhouse and keep plants alive on Mars. If I could afford it, I figured it would be a worthy expenditure of money, with no expectation of financial return.”