“ALMOST READY?” asks Leonel Perez, the National Masters Surf champion of Mexico. He asks me that every morning. Since I’m standing beside his two-door Chevy completely transfixed by the waves, and haven’t taken off my shirt or waxed my board聴and since it’s still dark, and we haven’t had breakfast or coffee聴I take it as a metaphysical question, like, Are you ready to believe in a force much bigger than you?

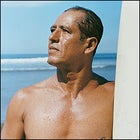

Leon Perez

Leon Perez, surfing mentor extraordinaire and Mexico’s National Masters Surf champion

Leon Perez, surfing mentor extraordinaire and Mexico’s National Masters Surf championLeon Perez

Perez’s trophy shrine, in Ixtapa

Perez’s trophy shrine, in IxtapaSurfing Mexico

Surfing Mexico

Leon Perez

EYES ON THE HORIZON: Leon Perez at El Rancho, a break north of Ixtapa

EYES ON THE HORIZON: Leon Perez at El Rancho, a break north of IxtapaLeon Perez

“SURF WHENEVER YOU CAN”: Perez riding the foam at a local break

“SURF WHENEVER YOU CAN”: Perez riding the foam at a local breakLeon Perez

LA VIDA PLAYA: The teacher walks to school.

LA VIDA PLAYA: The teacher walks to school.As I watch the tiers of surf near the Pacific resort town of Ixtapa, I realize that there are three things I appreciate about surfing as a near beginner: the raw beauty of waves; the anticipation of getting repeatedly thrashed; the possibility of one good ride, a kind of fleeting touch of grace. Also, my coach. I can’t believe he’s even standing up after last night’s party.

Leon rubs wax briskly over the deck of a board propped against his thigh. He is in training for the nationals in Baja’s Ensenada in two months, and he can’t bear to miss a wave. He is honing himself like a weapon. He doesn’t wear a rash guard or sunscreen. His baggy shorts come below his knees. He is 46 years old, short (about five foot six), broad-shouldered, and wiry. His ears are small. His nose, broken years ago, is slightly flattened. Even his buzzed hair is thinning, as if obliging a lifelong imperative toward sleekness. It occurs to me, watching him, that he is a man completely shaped by the sea.

Only four hours ago, Leon was working on his second bottle of tequila blanco. Caf茅 tables had been shoved together outside his surf shop, Catcha L’Ola (“Catch the Wave”), behind the row of tall hotels lining Ixtapa’s shore. A bunch of local surfers, four Texas longboarders, a pair of tourist police with shotguns, brothers and sisters of Leon, and two young women on holiday from Brooklyn were annihilating cases of Corona. The mother of Leon’s two-year-old daughter was warily grilling redfish. Leon worships his daughter, whom he named Auramar聴”Aura of the Sea”聴but only tolerates the mother, who, he says, tricked him into having a child and once threw stones at his girlfriend. The fiesta was in honor of his 46th birthday. Today would be another party. Three days ago was yet another bash, but nobody can remember what for.

“The waves look bigger today,” I suggest.

“There is a swell coming. You are ready.”

“I guess I am.”

Today I’m going to try a six-foot-six-inch shortboard for the first time, a personal threshold. I’m Leon’s age, and most guys who start surfing late stick with the more stable, less responsive longboards. To hell with that: I’m having a midlife crisis. This is my party and I can cry if I want to.

“You don’t even look hungover,” I say to Leon.

Now he looks up. He smiles聴I can tell because the left side of his mouth lifts just a little.

“Practice,” he says. He tosses the wax to me over the hood of the car and nods at the local kids carrying boards who are beginning to trickle in from the road. They have walked the last mile from the end of the bus route from Zihuatanejo, eight miles down the coast. They regard Leon with specific awe: He will catch many more waves than any of them today, and have better rides, which is unnatural, since some of the younger boys have grandfathers Leon’s age. Leon is nonchalant about his status as the old master. “I just surf every day,” he says simply.

I look behind us. Out of the mountains, unbending slowly from dense groves of coconut palms, pushes the sweet water of the Rio La Laja. The sun has not yet risen over the Sierra Madre del Sur, so the dark water reflects only a rose wash of dawn and the light of a single fisherman’s fire burning on the sand. The river cuts the beach and empties into the sea where the surf breaks over the sandbar. Even in the half-light I can see that the sets are easily head-high.

Leon straightens and turns toward the beach. And then, since he teaches with the minimalism of a Zen master, he gives me the lesson of the morning.

“Paddle toward the peaks. On that board, you have to be at the peak.”

“OK.”

“Lock the car door.”

“OK.”

Then he jogs toward the water.

I HAVE COME TO IXTAPA for three weeks to train with Leon. I started surfing six months ago, while visiting a friend in Huntington Beach, California, and got hooked. After 25 years of kayaking whitewater, it seemed a natural progression to begin again where the rivers end. I went back to California two more times last spring and now have a total of 35 days on a board. I wonder if, on day 365, I’ll be able to ride a North Shore Hawaiian tow-in wave like the ones you see on TV. I’ll need constant instruction to keep the learning curve steep. So when I met Leon while on a family vacation in Ixtapa last summer聴I’d already heard about him in California聴I asked him if he’d coach me.

It’s not surprising that Leon doesn’t believe in holding a student’s hand: All his life, his only teacher has been the thumping waves. As a small boy, living in a tiny village called Chutla, up the rugged Guerrero coast, he saw a neighbor who had been to California as a migrant worker wearing a T-shirt with a picture of a surfer shooting a tube. Six-year-old Leon kept thinking about that barrel. A few years later he began to see vans of American hippies with boards on the roof passing on the narrow, potholed coastal road. “I was thinking,” Leon says, pointing to his sun-burnished head, “I want to do that.”

When his father, a traveling electric-appliance salesman, moved the family to Zihuatanejo聴then a small beach town with one dirt road out to the highway聴Leon stole a scrap of plywood from a wood shop and began boogie-boarding. When he was 12, he heard that an American friend of Jacques Cousteau’s who lived across the bay had a longboard. Leon and a dozen other local kids asked to borrow it and took turns, and a local surf culture was born.

The same phenomenon of scrappy local kids hitting the waves any way they could was occurring up and down Mexico’s Pacific coast. Unlike California surfing, born in the early 1900s, the sport in Mexico didn’t have a direct pollination from Hawaii, with its centuries-old surf culture. There was no Duke Kahanamoku bringing showy exhibitions and aloha spirit; there were only wayward gringos. American legends Bud Browne and Greg Noll took some trips to Acapulco and Mazatl谩n in the late fifties, but, according to Nathan Myers, a historical-minded editor at Surfing Magazine, Californians didn’t start poking down the coast of mainland Mexico in significant numbers until the 1960s, after the Gidget movies and the Beach Boys craze had ignited the American surfing boom that suddenly crowded California’s beaches. The majority of the first Mexican surfers were the sons of poor fishermen and hotel workers. I asked Arturo Astudillo, now 52, one of the early Mexican pioneers around Acapulco, how he and his friends got their first boards. “We stole them,” he said. He hung his head. “I am sorry. It was the only way.”

By the late seventies, Leon, then a teenager, was shredding. He bargained with gringos for beat-up boards. He dripped candle wax on the deck for traction and made his own leashes out of surgical tubing. He began working in the booming new tourist center of Ixtapa. One morning, he and a friend named Antonio Ochoa paddled out into a wickedly fast hollow break beside Ixtapa’s recently built breakwater. No one had attempted it before. They dropped in on an overhead, right-breaking barrel that blasted them through a tube like buckshot. The wind at their backs almost flattened them. They came back the next morning, and the next, and named it Las Escolleras, “the Jetties.” Then they began exploring northward, finding the Rio La Laja break on the other side of a crocodile swamp.

They heard about a legendary Mexican surfer from Acapulco named Evencio Garcia Bibiano, who everybody said was like a demon on the waves. In 1978, they went to watch him compete at the first Mexican national competition on the mainland, at a break in Guerrero called Petacalco, a 15-foot barrel that broke dependably twice a day. Garcia, despite long nights spent partying, was beautiful, almost frightening, to watch.

Leon never missed a day on the waves. When he was 24, he became a waiter at the club Carlos ‘n Charlie’s, right on the beach in Ixtapa, a five-minute walk from the Jetties. At Carlos ‘n Charlie’s, every night is spring break, and Leon quickly became chief party maker. He wore his shirt unbuttoned to his waist, danced on the tables, judged bikini contests, administered a devastating sangria from a spouting pitcher. He knocked back tequila every night and was such a ladies’ man that he is still called El Tigre. He dated models and TV stars, often didn’t sleep, and, when the sun came up, grabbed his board and went surfing. When the onshore winds blew out the waves in the late morning, he’d nap for a couple of hours, then come back to the bar and load up the donkey with buckets of ice and beer.

“The donkey’s name was Lorenzo,” Leon said. “We shared free beers on the beach, for advertising. As soon as he saw me open the first beer, he chased me down. I taught him to drink. By the time we came back, he was drunk.”

“Too much party,” Leon admits. After 15 years in the fastest lane, he downshifted to a slower one, surfing with single-minded devotion and opening his shop. He, a sister, and two youngerbrothers started renting boards, giving lessons, and taking customers on day trips to nearby breaks. And once Leon got serious about competing, he won the nationals in his age class聴over-40 in 2002 and over-35 in 2004. There are few men alive who know the Pacific coast of Mexico as well as Leon.

I CHANGE INTO A SNUG RASH GUARD, lock the car, and pick up the six-and-a-half-foot board. By now there are a dozen surfers bobbing 30 yards offshore. I don’t want to compete for waves today, but if I did, these teenagers聴unlike the locals in California聴wouldn’t mind. They’re tolerant, even encouraging. Yesterday, when I collided with a local kid聴my bad聴he didn’t emerge from the tumble yelling, “You !@#$ing kook, get the !@#$ out of the water!” I said, “Lo siento,” and he shrugged and smiled, as if to say, “Don’t worry, we all sucked at the beginning.”

The air is chilly. I turn down a smooth path toward the river. Beyond the far bank is a curve of desolate beach that stretches for miles. Out in what seems to be the middle of this shallow bay, I can see the swell form and break. I can see the small figures of four surfers.

At a tangled pile of drift logs, I unwind the leash from the board and secure the Velcro strap at my ankle. Then I wait for a little shore wave to break, jog into the water, jump onto the board, and start to paddle. The strong tug of the rip current pulls northward. I make it over a few steep swells and hit a low ridge of whitewater, paddling hard. It floods over me, stops my progress. I bob up paddling like a possessed turtle, shoulders burning, and when I shake my eyes clear, the only thing in front of me is a pelican and a head-high wall already breaking. Oh, shit. Duck-dive! Wait until the white pile is almost on top of you. Big breath. Rock the nose down hard with both hands, press the tail down with one foot . . . Yes! When I buoy to the top, the wave is past. Dang. “Paddle again even before you can see,” Leon said. I do and make it over the next wave just as it peaks. And then there’s only open, rolling water. Phew. For me, there is always this race to get past the break, always a little desperate.

I catch my breath and look left in time to see Leon hunting the next set. While the other three surfers are just sitting on their boards, he is already moving, paddling smooth and fast, angling both toward deeper water and down the beach. Abruptly, he spins. He is just in front of a perfect peak, the rounded top of a glassy, inexorably forming mountain. No one else has seen it coming. And then he is an explosion of motion. “Everything moves,” a local told me with a grin, describing Leon catching a wave: His arms windmill, his feet kick in a violent flurry. But what you remember most is his expression: He looks like a gunfighter in the middle of a fast draw against five men. When the wave is steepest, hanging for a split second at its own angle of repose, with just the top beginning to fold, Leon is up, rocketing left down the wall with the speed of a diving tern. He is crouched, perfectly balanced, the wave ripping white down the line, unpeeling behind him and trying to devour him like a jaw. He stands upright and pumps, bouncing the front of his board for more speed, swings up to the stiff lip, and caroms down off it in another crouching swoop. I laugh out loud.

I am thinking, like the six-year-old Leon, I want to do that.

TEN MEXICAN STATES NOW HOLD CIRCUITS of torneos to select teams to go to the annual nationals. Each will send as many as 30 competitors in all categories. Serious surf competition in Mexico is booming, the result of a maturing homegrown scene fueled by access to global culture via the Internet, movies, and television. While there are no Mexicans on the World Pro Tour, and their best surfers need more pro experience to be truly competitive, the nation has fielded surf teams to the World Games in Brazil, Ecuador, and South Africa in the past five years. Two contenders of note: Raul Noyola became the first Mexican surfer to win a World Qualifying Series pro-tour competition in 2001 and, last August, won the Mexpipe Open, in Puerto Escondido; and one of the country’s best female surfers, 20-year-old Sofia Melgoza, of Guadalajara, has had promising results in international events. Meanwhile, surf clothing and gear companies聴like Mexpipe, Olea, and Squalo, the biggest, which operates 50 clothing retail stores in Mexico聴are springing up and providing sponsorship for competitions and individuals. Mexican shapers are producing beautiful boards in Cabo and Puerto Escondido.

On my fifth day in Mexico, Leon and I drove the five hours down the coast to Acapulco for the Torneo Evencio Garcia Bibiano, a Guerrero State selection qualifier that Leon would have to win in order to go to Ensenada. Garcia, for whom the competition was named, was the legend Leon had first seen compete in ’78. He was from Acapulco, and at a 1985 championship here at Playa Bonfil, south of town, he used the home-field advantage and devastated the competition. He was a quintessential fearless big-wave rider and the first native to do aerials and floaters and 360s. On his last heat, he already had more than enough points to take first place, but he had a few minutes left before the horn, so he paddled back out for one more ride聴just for show. Before a crowd of a thousand spectators, he took off on a steep left, and it closed out and collapsed. He seemed to kick out over the back side. His board flew into the air, then . . . nothing. The board washed onto the beach, and no one ever saw him again.

In a superstitious culture, Garcia has become the resident spirit of Mexico’s waves. Surfers will tell you with a straight face he was transformed instantly into a dolphin who still patrols and protects surfers. He was El Campe贸n, “the Champion,” claimed by heaven, and every time a wall of green water rises out of the sea, a surfer may sense Garcia’s ghost gliding like a dolphin down the line. I met a 25-year-old top surfer named Julio Cesar La Palma, whom everyone calls La Pulga聴”the Flea”聴and when I asked him if he has a hero, he blinked and put his hand on his chest. “Sometimes when I dream,” he said, “I dream that Evencio Garcia is surfing in my body.”

If Garcia were there on that Sunday in November, he would certainly have heard “Guantanamera” booming out of the giant speakers next to the judges’ platform聴not the old song but the hip-hop version by Wyclef Jean, Celia Cruz, and Lauryn Hill. Leon was out in the surf loosening up. I recognized him right away even from a distance聴his bullet head, his constant roving back and forth, hunting. In surf, he rarely stops paddling, even between sets, his eyes on the horizon.

“骋耻补苍迟补苍补尘别别别谤补聴“

According to the big posted roster, Leon’s finals heat was coming up. At the top of some crumbling steps off the sand, wedged between a palm tree and a shaded slab of concrete covered with plastic chairs, where surfers were eating sopa de mariscos (seafood soup), was a beat-up white Chevy van with PRENSA painted in block letters across the front. It didn’t look like any press van I’d ever seen. A wooden skeleton in sunglasses was chained to the grille. A faded Xerox of a dog was taped to a window, with the words CUIDADO! PELIGROSO! I could see why: Chained underneath were two tawny pit bulls.

A short, thin-faced young man with a sparse mustache hustled around from the back of the van. His loose hair hung down his shirtless back. He had skull tattoos and a skull pendant, and his official government press card hung on a necklace of shells and claws of black coral, along with a fancy Nikon. I introduced myself, and he ducked his head agreeably. “Andale,” he said, and pushed aside a bamboo curtain across the van’s open side door. He sat against a bag of dog food, under a poster of Bob Marley.

Oscar Diego Morales, a.k.a. “Fly,” is a roving reporter for Planeta Surf La Revista, a magazine by, for, and about Mexican surfers. It’s slick and fun, splashed with Aztec design motifs, crisp action photos, and ads for Mexican beachwear. The second issue had just hit the stands. Oscar told me that surfing in Mexico was at a tipping point. It was growing more popular by the month. “Every time a good swell is forecast, more and more people come out,” he said. Then suddenly, hearing a particularly irresistible riff from the speakers on the beach, Oscar leaped out of his seat and, bent over, began to do a crazy little dance to the music. He sat back down. I asked him how many dedicated surfers he thought there were now in the country, and he began, remarkably, to tick off each major break.

“Puerto Escondido, 60 . . . Acapulco, 25 . . . Ensenada, 50 . . . Mazatl谩n, 15 . . . San Blas, 15. Nobody knows,” he concluded. (Matt Warshaw, who wrote the seminal Encyclopedia of Surfing, estimates there are 30,000 native surfers in the country, though Mexicans say there are far fewer.)

“What’s with the skulls everywhere?” I asked.

“Skulls? Oh. No matter if you have green eyes, blue eyes, white skin聴in the end everybody is going to be the skull. It’s the true face at the end of our life.”

As I left the van, a small pickup skidded to a stop at the end of the sand street, and ten shirtless teens with boogie boards and shortboards jumped out. Some had fade haircuts with long, red-streaked tops. Earrings, eyebrow piercings, blond-streaked ponytails.

“Hey,” I called, “where are you guys from?”

Playa Princesa, a break a few miles up the coast.

“Are you students?”

Most of them worked as lifeguards and in restaurants for a few dollars a day. Another generation.

Back down on the beach, I found Leon. His final master’s heat was about to start. He was with some other surfers in the shade of a palapa, stretched out in a plastic chair, drinking from a water bottle. He looked much too relaxed.

“Isn’t your heat coming up?”

“In a few minutes. I am ready.” I was more nervous than he was. I felt like a soccer dad.

We heard the blast of a horn announcing five minutes to go. Leon stood, stretched his arms back like a man waking up, grabbed his tiny board. How long can a warrior keep going to war? He reminded me of the graying soldier in The Seven Samurai, the one who would always survive on seasoned judgment, discipline, and patience. Then it occurred to me that I was Leon’s age and I was just starting. What would I survive on?

TWENTY MINUTES LATER, Leon won his final heat handily. He was now a Guerrero State champion, heading to the nationals. He also won the open longboard class. He shrugged it off. That night, after four days in Acapulco, we drove back up the coast to Ixtapa in the dark. We arrived too late to find a room for me, so I slept on the floor of his apartment, in a concrete block at the edge of the tourist zone, crowded by jungle. I slept under a shelf of trophies, a rack of six bagged boards, and a photo collage of Leon’s younger brother Alejandro, who died in a motorcycle wreck 14 years ago. The young man held a surfboard in half the pictures, was as handsome as Leon, and looked very happy. “His nickname was Karma,” Leon said before he turned in. “Everybody loved him. He was a very good surfer. That is why we name the annual tournament in Ixtapa 聭the Karma.’ ” I saw a flicker of emotion cross Leon’s usually inscrutable face. Then he said, “You have been working hard. You can do it, the big wave. Practice more. Tomorrow I will take you north.” Then he flicked off the light. I went to sleep listening to the calls of a loud night bird and thinking how everything is connected: Evencio and La Pulga; Leon and his brother Alejandro; Antonio Ochoa and Oscar and me. And the waves out of the Pacific, which were now pounding the long, empty coast in the dark.

The next morning, Leon jostled me awake in pitch blackness.

“Almost ready?”

“Are you crazy?” I could see his white teeth floating like a canted moon. First we surfed Rio La Laja, and then we started driving north. We passed through the industrial town of L谩zaro C谩rdenas, where the legendary tube of Petacalco used to break, before they built a dam on the Rio Balsas. We drove into the desolate, lovely country of Michoac谩n. Tall saguaro cactuses came down to the beaches. The road snaked over high bluffs and around rock coves that cradled blue water. We drove in third gear. The foothills were covered with white-flowering bogote trees, and rioting bougainvillea edged the dooryards of the sparse villages. It was like a more tortured Highway 1, but empty, with the Pacific crashing on the rocky points and fringing the long beaches with peeling waves. Mainland Mexico has 2,500 miles of Pacific coastline聴enough surf for a millennium.

Leon and I spent three days at Rio Nexpa, where there is no phone or running freshwater, just a point break and a beach break going off all at once and a long, cupped strand with a few dozen thatch-roofed cabins built for surfers, each with a balcony and a hammock. On the second evening, Leon sat on the porch rail, drinking a beer, looking out at the ocean. I swung in the hammock, replaying in my head a long ride I’d had that afternoon. A surprising set had loomed, and I found myself in position, suddenly taking off on a fast overhead left and looking down at the pod of other surfers, who seemed far below. Some cheered. I popped up and crouched, and when I’d gotten ahead of the crashing white, I roller-coastered to the top of the lip and shot back down. I did it again and again. The sensation was one of the finest I’d ever had. In my life.

“Look at the moon,” Leon said. It was nearly full, rising out of the palms past the point. The sun was still a few degrees off the water, burnishing the tiers of breaking waves. A faint onshore breeze brought in the sound, a rhythmic thresh almost like breath. I didn’t think he was waxing poetic聴I knew what he was thinking: After the sun went down, there would always be the moon. He was already taking off his shirt.

“Aren’t you tired?” I said. I think we’d surfed five hours already.

“A little. Almost ready?”

I stared at him. I burst out laughing. “What’s my lesson for the day? You forgot to give it to me.”

The left side of his mouth lifted just a little. “Surf whenever you can.”

Salsipuedes

About an hour south of the border, this point/reef break (the name translates as “Leave If You Can”) boasts good lefts and a long, heavy right.

Islas de Todos Santos

If you’re crazy enough to surf Killers, one of North America’s biggest waves, or just want to have a look, hire a fishing boat out of Ensenada for an hour-plus chug.

Isla Natividad

Open Doors, a world-class beach break, draws surfers to this otherwise isolated island, reachable only by boat or plane.

Los Pinos

Also called Cannons, the reef-rock left is visible from Mazatl谩n’s coastal strip.

Pascuales

If you can avoid getting obliterated by this pounding beach break聴Puerto Escondido’s little brother聴you’ll get the tube of your life.

La Ticla

A classic left point break and a less consistent right, with a charming town a few minutes’ walk from the water.

Rio Nexpa

On a good day, Nexpa could be called Mexico’s best wave. The left point break peels for 200 yards, with barreling sections.

Puerto Escondido

One of the world’s heaviest, hollowest beach breaks, the experts-only Mexican Pipeline will break your board, your bones, and your pride, and keep you coming back for more.