Ask anyone who’s been around Grand Canyon for a while about Georgie White Clark and they’ll have a story to tell you. Retired river historian Roy Webb remembers meeting Clark at Lees Ferry in 1986. She was 76 at the time. “There was this massive rubber boat on the ramp, a giant pile of ropes and rubber. This lady popped up out of the back and said, ‘What are you looking at?’” Webb says.

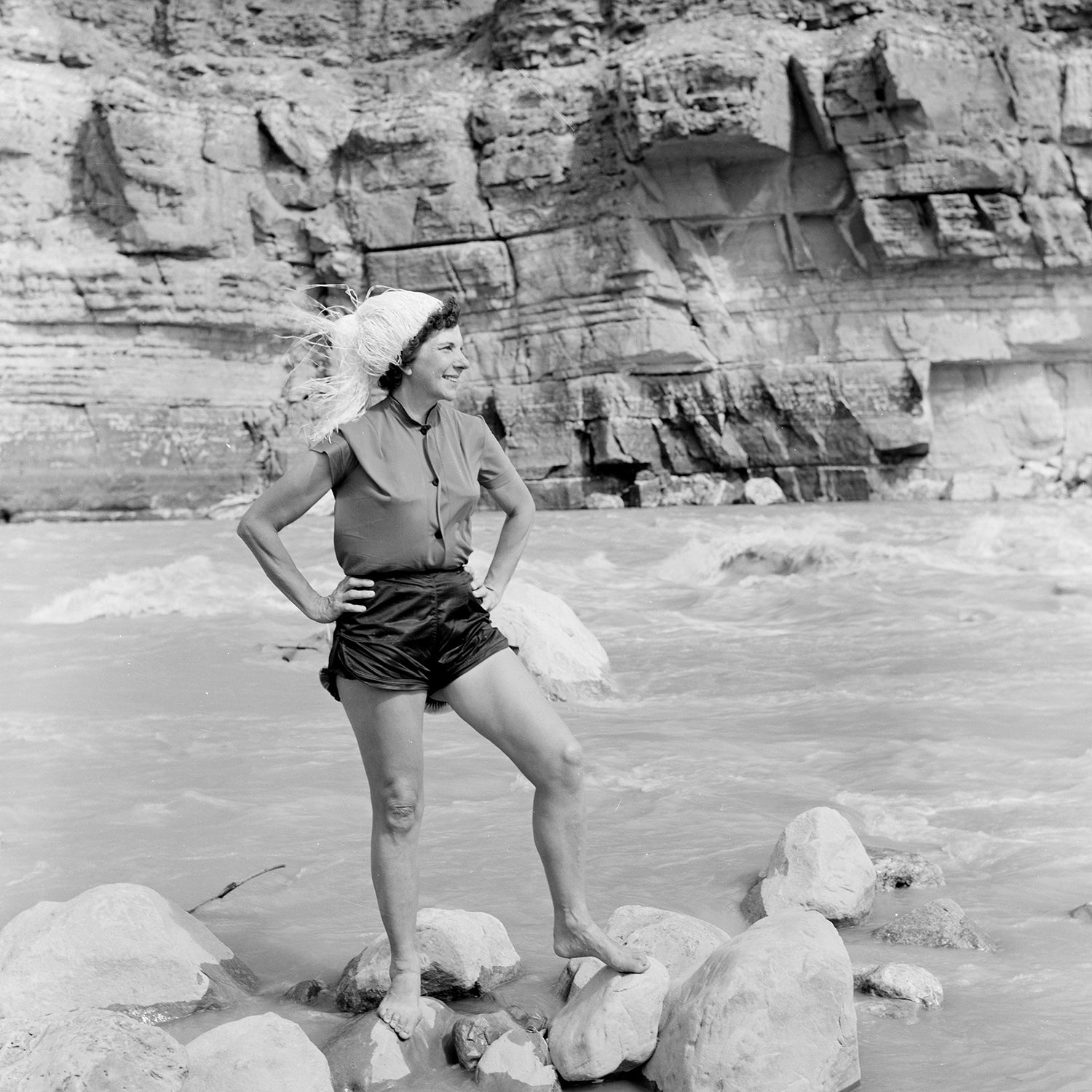

Clark was famous for pioneering commercial rafting in Grand Canyon in the 1940s and being among the first to use inflatable rubber boats. But she was also controversial—Clark went on TV to pitch her inexpensive, no-frills trips down the biggest whitewater in America, which brought in mass tourism like the canyon had never seen before.

“There was this tension between people who felt like her groups were too large and those who wanted to keep it small and intimate,” says Brian Merrill, CEO of , a Grand Canyon outfitter since 1961. “Some people saw her as revolutionary, and others didn’t like what she was doing at all.”

In the 1970s, Clark’s trips cost $300 for a ten-day journey, while other outfitters were charging guests three times that price. In total, Clark led more than 12,000 people down the river during her 45-year career. “In those days, the Grand Canyon was an elite place where manly men went down in boats,” Webb says. “People didn’t like that Georgie introduced mass tourism and low-cost river running. But she introduced so many people to what had been an exclusive adventure.”

Clark was born in Oklahoma in 1910 and grew up in Denver. She married and divorced twice; in 1944, her 15-year-old daughter, Sommona Rose, was killed in a bicycle accident while they were riding together in California. Many say it was the grief of losing her daughter that drove Clark to Grand Canyon. That, and the fact that her friend Harry Aleson invited her there. In 1945, the duo swam 60 miles of the Colorado River in life jackets, toting a backpack with instant coffee and dehydrated soup, for four days on the river.

The next year, Clark and Aleson hiked in and floated the river in an Army Air Corp rescue raft. By 1947, she brought her first paid clients down the river. Clark launched her own company, Georgie’s Royal River Rats, with army surplus rubber rafts.

On the river, Clark famously wore a leopard-print leotard and lived on tomatoes, cheese, and Coors beer.

In the early 1950s, Clark used ropes to lash three rubber rafts together, with a motor on the end, to create a sturdier ride. They became known as G-Rigs; the “G” stood for Georgie. She’d point her flotilla straight into the rapids, squat in the back, and hope for the best. “People were thrown off her boats all the time,” Webb says. Clark later hired Los Angeles firefighters as guides, because they’d work for free and had good safety training.

“The difference between me and the men was I plowed through the rapids while the guys carried their boats around the rough water,” Clark once said.

There was nothing royal about her trips. For dinner, Clark would put canned food into a bucket of hot water so the labels would fall off. Guests would grab a can and get whatever was inside—ham, corn, lima beans. If people complained about the food, her response was always, “Did you come to eat or did you come to see the canyon?”

On the river, Clark famously wore a leopard-print leotard and lived on tomatoes, cheese, and Coors beer. When the National Park Service insisted she feed her clients salad, Clark started serving plain lettuce. “Nobody cared about gourmet meals,” says Roz Jirge, who worked with Clark for 12 years. “They were there for an adventure. But it was definitely very Spartan.”

At the end of the trip, Clark would line up her clients, whack them in the butt with a paddle, dump mud on them, and hand them blackberry brandy. They’d earn a pin, declaring them a Royal River Rat. “It was a badge of honor to complete one of her trips,” Webb says.

“She was definitely her own person, doing what she wanted to do,” says Clark’s friend Sue Holladay, co-founder of Holladay River Expeditions. “Here was this woman, running her own business, doing the things men were doing. She stood for what she believed in.”

Clark ran the river for the last time just before her 80th birthday. At her birthday party that year, hundreds of people showed up to celebrate at ’ metal warehouse. A band played, and there was a cake in the shape of her boat. Clark wore the same red cape she’d worn on countless other trips.

Soon after, Clark was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. She refused treatment and made arrangements to sell the contract from her company to Western River Expeditions. “Her main ambition in life was to keep running that river,” Jirge says.

Clark died in 1992 at the age of 81. Soon after, Jirge began the process of trying to get a rapid named after her friend. Nearly a decade later, in 2001, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names changed the name of a spunky little rapid at mile 24 to Georgie.