The Incredible True Story of the Henrietta C.

From miles out in the storm-ravaged Chesapeake Bay, the Tangier Island crab boat radioed a mayday, then fell silent. Fellow skippers from this lonely and legendary speck of land rallied to save the two-man crew. God willing, they'd get there in time.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

That Monday opened with winds coming steady out of the east-northeast at 20 to 25, or kyowking, as they say on Virginia’s Tangier Island.

It’s one of many old and strange words used by the people there: kyowking, or blowing hard. A day unfit for pleasure craft and weekend sailors.

But April 24, 2017, was also a workday, and for 72 of the island’s watermen, that meant venturing out into the Chesapeake Bay to harvest its famed blue crabs. The people who came down to the docks that morning lived on a lump of mud and marsh about 12 miles from the mainland. It was, and is, one of the most isolated communities in the East, marooned from the rest of America by 18 trillion gallons of tempestuous water. Tangiermen had braved the bay’s moods since the American Revolution. They knew wind and waves.

So it was that at five o’clock that blustery morning, Edward Vaughn Charnock and his son, Jason, slacked the lines on Ed’s workboat, the Henrietta C., and chugged west from the harbor in the predawn dark. They motored out past the protection of the island’s low, crumbling shoreline, leaving behind a homeplace with traditions of long ago and a style of speech that harks back to Cornish settlers two centuries past.

They left behind a village of 460 residents, with small weatherboard houses and lanes no wider than sidewalks. A place without mobile-phone service or a resident doctor. A near theocracy of old-school Christians who don’t allow the sale of alcohol and believe themselves an anointed people, armored by faith against the hurricanes that often pass near. Rising in the gloom behind the Henrietta C. was the town’s water tower, emblazoned with a bright orange crab facing east and, to the west, a Gothic cross.

The Charnocks had little reason to think their faith would be tested that day, or that the hours ahead would call on Tangier Island’s proud traditions of courage and selflessness. They knew that the conditions, already brisk, were expected to sour—that the afternoon spoke of wind, as Tangiermen say, and would “breeze up” to 30 or 35 miles per hour. But father and son planned to quit before the weather turned mean. They’d fish up 300 pots or so, more if they had time.

They’d fish up their pots and be home in time for lunch.

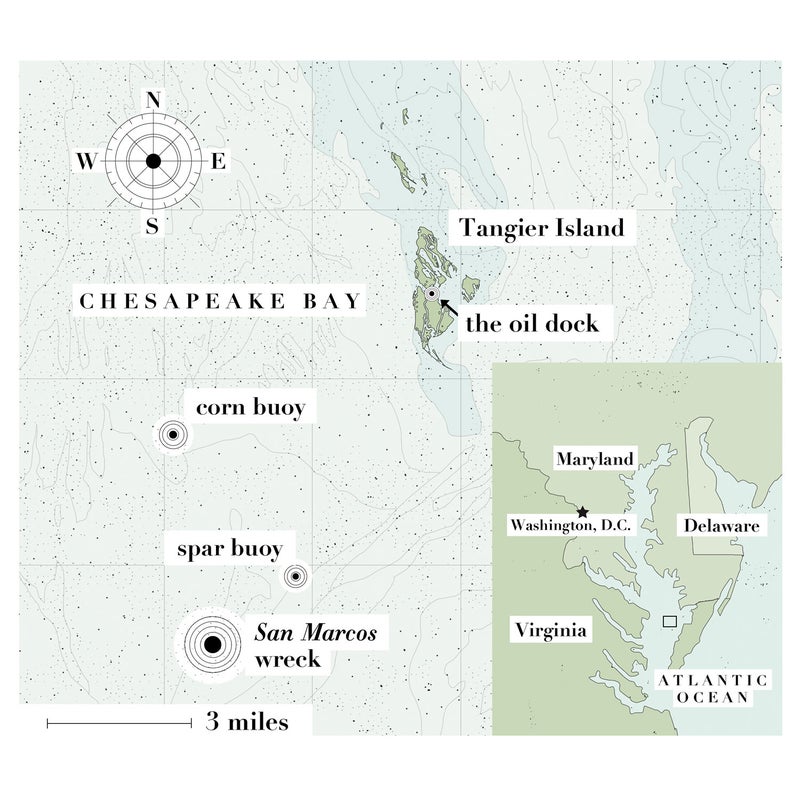

The is America’s largest estuary, a mixing bowl of oceanic salt water and the flow of the mid-Atlantic’s big rivers—the Susquehanna and Potomac, the Rappahannock and York, the James. It stretches 200 miles south from Havre de Grace, Maryland, to a gaping junction with the Atlantic at Virginia Beach. The bay’s Maryland waters are never so wide that the far shore isn’t visible. But near the zigzagging imaginary line that crosses the bay and marks the Virginia border, the Chesapeake broadens to 30 miles. It’s here, dead center, that Ed and Jason Charnock lived, and it was into the big water west of the island that they pressed that morning.

Ed Charnock—Eddie Jacks to his friends—was cousin to most of his neighbors, and like them descended from a single family, the Crocketts, who arrived in 1778. Like most island men his age, he’d quit school in his teens to follow the water. He had since lived a virtually amphibious existence, chasing crustaceans prized for their sweet, juicy meat, from a village famed for catching more of them than anywhere else. No community in the bay is so identified with the blue crab, so economically bound to the small but com-bative creature, as Tangier.

At 70, Eddie Jacks looked like a character straight out of Coleridge: six feet tall and powerfully built, with a square jaw and a face lined and chapped by sun and salt. He was one of the most capable watermen on an island of experts, but he was shy and laconic, predisposed to spend his tight budget of words poking fun at himself. He joked that he was flat broke, near starving. He brushed off talk that he could think like a crab, claiming he was no wiser about the animal than when he’d started crabbing 54 years before. All he knew for sure, he once said, was that “she’ll run from you, and she’ll bite.”

Jason Charnock had grown up working summers and Saturdays with his father, and had been Ed’s full-time mate since graduating from Tangier’s K-through-12 school in 1994. Stocky and strong at 40, he lived with his wife and four young children in a toy-strewn house 400 feet from Ed’s.

The Charnocks ranged far, farther than many a crabber, and they did today. They had their 425 pots arranged in six rows on the bottom of the bay. The first two ran in parallel lines near a submerged wreck about seven miles southwest of Tangier—the U.S. Navy’s oldest battleship, the Texas, later renamed the San Marcos and parked there in 1911 as a gunnery target. The rest of their pots were five miles farther southwest, near the channel used by big ships plying the bay to Baltimore, a dozen miles from Tangier and a long way from anywhere else.

Eddie Jacks and Jason were undaunted; they knew their business and drove a time-proven craft. The Henrietta C. was a classic Chesapeake Bay deadrise and, at 43 feet long and 13 wide, big enough to handle a choppy day. Like all of its kind, it had a small cabin positioned up near the bow, a long open-weather deck aft of the cabin, and steering consoles both inside and out, so a captain could control the boat while tending to pots. In profile it swooped from a high bow to a stern that rode low, just two feet off the water.

The Henrietta C. had been hand-built for Ed by one of his closest friends, Jerry Frank Pruitt. Pruitt never wrote down a measurement—he kept them all in his head—and had built some of the strongest and most well-mannered wooden boats on the bay. Made of fir and southern yellow pine, the Henrietta C. was a visual song.

Ed had named it for his first wife, Jason’s mother, later lost to cancer. Twenty-eight years he’d had the boat, and he wasn’t one to baby it: he’d driven it hard, in all kinds of weather. The Henrietta C. had always been up for it.

It was just shy of sunrise when they reached their first pots and stepped into their oilskins. Ed, working the outside steering console, would sidle the boat up to a foam buoy linked to a pot resting on the bay’s floor, lean over the starboard side to snag it with a hook, and feed the line into a motorized pot puller. With a few seconds of spinning, the device would haul the pot to the surface.

Pot is a misnomer. They’re traps: wire-mesh cubes two feet to a side, with four tapering “throats,” or funnels, opening to the interior. Crabs crawl through the passages to get in, but they can’t easily find a way back out.

Once a pot was aboard, they’d dump the catch, close and rebait the trap, and toss it overboard. In the minute it took them to putter 30 yards to the next buoy, they would cull the catch, sorting by size and sex. This time of year, the biggest males, or “jimmies,” would bring $100 a bushel.

They tried the nearest two rows first, close to the San Marcos. The results were disappointing. After checking 30 pots and finding few crabs, the men decided to head for the four outer rows, which sat in deeper water. On the way, they passed Paul Wheatley in the Elizabeth Kelly. He was Ed’s son-in-law, married to the eldest Charnock daughter, Kelly. Ed’s grandson, Jonathon, was his mate. Everyone waved.

Out by the shipping channel their luck improved. The pots came up loaded, and they filled one bushel basket after another. But as they worked their rows, the wind picked up. By midmorning it was blowing 25 to 30. It had a lot of fetch before reaching the Henrietta C.—a lot of room, unbroken by land, to push water around. To build waves.

The seas sprang to four feet. Spray blew off their crests; the wind swept cold over the boat, and the deck pitched under the men’s boots. It was becoming the kind of morning that islanders, prone to saying the opposite of what they mean, summarize with: “It ain’t blowin’ none.” The Charnocks stayed alert to the weather but kept to their work.

Another man of 70 years might have found a reason to stay ashore that day, and Eddie Jacks wouldn’t have had to look far for one. He was nursing a hernia, for starters. And then there was Annette.

Two years after Henrietta’s death, Ed married island-born Annette Pruitt Beatty. Living on the mainland since leaving for college in 1970, she had married a mainlander, raised three children, taught first grade, divorced. Then, after 36 years, friends set her up with the quiet, deeply religious Ed. Their courtship started slowly—it took him weeks to work up the nerve to call her—but by their third date they were already talking about marriage. Annette had moved back, and they’d been together ten years.

Annette was Ed’s opposite—daring, outgoing, opinionated, with the laugh of an optimist and a fondness for dancing. She lured him onto his first plane ride, to Mexico, and talked him into a cruise around the Caribbean. She introduced him to fine restaurants and big cities; he told her he felt like Crocodile Dundee. The whole island thought she was good for him.

Annette wasn’t keen on Ed working in rough weather. But all who knew him knew that the man loved crab potting. Once, when he heard the Virginia Lottery was offering a jackpot in the hundreds of millions, he deadpanned: “If I won that, I could buy a lot of crabbing supplies.”

There was another reason Ed was inclined to take the boat out. Having raised four children, he understood the money pressures his son faced, and worried that if they stayed in, it might be a hardship for Jason. That was one of the reasons he’d put off surgery to repair his hernia—the Henrietta C. would be idle while he recovered.

So out they’d come, father and son, and the crabbing was good. By late morning they had fished up only two-thirds of their pots, yet the open deck was crowded with 36 bushels. At that point, the wind still rising, they decided to pack it in.

They set off to the northeast, against the building seas, Ed pushing the boat. It was slow going, especially with something like 1,400 pounds of crab aboard. They were halfway home, moving just past the San Marcos at about 12:45 p.m., when they noticed that the boat felt soft. It wasn’t quick to answer turns of the wheel; it seemed lazy, wallowing.

The Henrietta C. was taking on water. This in itself was no cause for alarm—water finds its way into a wooden boat as a matter of course. Still, they needed to address it. With water in the hull the boat sat lower, which slowed it down, forced its diesel engine to work harder, and made it more susceptible to waves over the stern.

Jason guessed that they had taken on quite a bit. As they dived into troughs, he could sense weight shifting to the bow, driving it down. When they rode a wave up, he could feel the heaviness slide aft.

A workboat relies on two pieces of equipment to clear water from its bilge, the dark space below deck. The first is a bilge pump, which operates like a basement sump pump: tripped on by the presence of water, it runs until the water’s gone. The Henrietta C. had two of them, one on its port side, another starboard. The starboard pump had been busted for a while, but the port-side machine was working fine.

The second piece of equipment is an automatic bailer, a device with no moving parts. It’s essentially a short brass pipe, 1.5 inches across, that passes straight down through a boat’s bottom. The vessel’s forward movement creates a vacuum at the pipe’s lower end, which sucks water out and overboard. Bailers are capped when not in use, and usually reached via a hatch in the deck just aft of the engine.

Ed told his son to take the helm while he uncapped the bailer and kept it clear. A day’s crabbing dumps all manner of debris on the deck—bits of crab shell, sea grass, splinters from wooden bushel baskets—and some of it inevitably works its way through the deck and into the bilge, where it can clog a pump or choke the bailer. Ed opened the hatch, got on his knees, and reached almost shoulder-deep to unscrew the bailer cap. Most of his arm was in water.

Eddie Jacks looked like a character straight out of Coleridge: six feet tall and powerfully built, with a square jaw and a face lined and chapped by sun and salt.

In the cabin, Jason recalled the many times he and his dad had found themselves in heavy weather. They’d seen worse, for sure—but not by much. The seas were running five feet now, and the marine radio crackled with watermen talking about how rough it was. One was Jason’s father-in-law, Lonnie Moore, an able and aggressive crabber headed for Tangier with his limit of crabs. Lonnie’s boat, the Alona Rahab, was also riding low under its load, and he was having to take his time crossing Tangier Sound, on the island’s east side. Rocking and rolling, the radio chatter went. She’s a-blowing out here. These waves ain’t big at all.

If you think it’s rough there, Jason radioed, you ought to see how nasty it is over this way.

Supposed to be even rougher tomorrow, someone said. Ain’t no way, Jason replied. You won’t see me out here if it is.

Out on deck, Ed still had an arm down the hatch. The bailer wasn’t pulling any water. Slow as they were moving, the pipe wasn’t creating a vacuum under the boat.

They knew what to do: turn from the wind, get up some speed, get the suction going.

It was counterintuitive, to steer away from home, but with the wind hitting them “right in the painter holes,” as Tangiermen say, they were crawling anyway. Still, Jason hated the idea of surrendering all the progress they’d made, so rather than put their tail full to the wind, he decided they would run solid to it—turn to the northwest, with the wind hitting them abeam.

With Jason at the helm, Ed out on deck, the Henrietta C. swung wide and put its starboard side to the wind. They got up some speed. The bailer pulled water. Lonnie Moore, reaching the safety of the harbor, radioed: Are you OK?

Yes, Jason replied. Everything’s fine. We got some water in, but no concern. We’re going to run solid to it until we got it out.

For a while after that exchange, the going was smoother. The waves pounded a little less stridently on the hull as they labored to the northwest. They might get home late, but they’d see Tangier before dark.

Except that the Henrietta C. wasn’t clearing the water in its bilge, even as the boat gained speed. The bailer was working, sucking water at a furious rate. The sole bilge pump was drawing hard. But the flooding in the boat’s bottom was as bad as ever: Water seemed to be piling in, and the pipe and pump couldn’t keep up. What was going on? Where was all this water coming from?

It was then, as the boat slogged heavier through the chop, that Jason noticed something he’d never seen before: water was seeping into the cabin, collecting on the deck. He checked the windows. No leak.

It took him a moment to put it together. It was coming up through the floor.

With that the bilge pump died, and their situation shifted from inconvenience to emergency. Now the bailer was the only route for all this water to leave the Henrietta C., and it was clearly no match for the load.

Jason tried an emergency maneuver. He turned the boat away from the wind and opened the throttle wide. The Henrietta C. surged westward, running with the storm. So it ran, right up until the engine quit.

The deadrise fell weirdly quiet, the only sound the pounding of water on wood. Ed shouted from the stern: Jason, you better holler for somebody. And get your oilskins off. Take them off right now.

Eddie Jacks: nicknamed for a character on the old TV melodrama Peyton Place—a sinister character, which didn’t fit Ed in the least. He’d been raised in a household guided by scripture, had spent his childhood Sundays in the austere New Testament Church, a renegade splinter of the island’s Methodist majority. Even on devout Tangier, members of the New Testament flock were called

Holy Rollers.

Ed still went to church every Sunday, only these days he did so at Swain Memorial United Methodist, a grand old wood-frame structure that served a congregation dating back to 1807. He could quote Bible verses off the top of his head. Was known to say, “If you don’t pay attention to those red-letter words in the Bible, there ain’t no need to worry about everything else.”

His time on the water had reinforced his faith, as it is wont to do, for a Tangierman encounters nature at its capricious worst. He chases blue crabs from March to November, dredges oysters December through February, and braves rough conditions throughout. The Chesapeake Bay is shallow, with an average depth of only 21 feet, but its temper can shift from one minute to the next, and among those who work the shallow-draft boats suited to crabbing, its waves can inspire real fear. “You better know what to be afraid of,” Ed once said, “or you get drownded.”

Coming ashore doesn’t completely safeguard the waterman from the bay’s muscle. Tangier Island itself is sinking, actually subsiding into the earth’s crust, as the water around it rises. Two-thirds of the island has washed away since 1850. Now it’s been whittled to about a mile wide by three miles long, most of that marshland that barely clears the tide. Most years the island’s edges recede by 15 feet or more. A 2015 study reckoned that the rising waters might well produce the country’s first climate-change refugees; its lead author thinks the island will probably be uninhabitable within 25 years.

So Tangiermen pray. On the Henrietta C.’s cabin wall was a framed print of “Christ Our Pilot,” painted by a Chicago artist in 1950. It depicts a young mariner at the wheel of a sailing ship in the grip of a terrible storm. A ghostly Jesus stands behind him, one hand on the sailor’s shoulder, the other pointing the way to safety. The image is standard equipment aboard Tangier workboats, an acknowledgment that faith is sometimes the best protection a waterman has.

Sometimes it’s all he has.

In the cabin, water sloshed around Jason’s ankles. He tore off his oilskins and reached for the radio. He knew it was past workday’s end for most Tangier crabbers, who would have turned off their two-ways. Even if a few boats were still out, they were miles away—and, with the storm raging, probably beyond range. Still, Jason keyed the mike. Does anybody hear this radio? he shouted.

No answer. Water swirled cold around his legs, creeping higher. Does anybody hear this radio? he yelled again.

A squawking voice: Yeah, I hear you.

It was Billy Brown, a Tangierman bucking the wind into Crisfield, Maryland, with his day’s catch of crabs. He was 16, 17 miles to the northeast. Amazing that he’d heard.

We’re in trouble, Jason told Billy. Taking on water, a lot of it. We need help. Better get ahold of somebody.

Billy, against a background of static: Who should I call?

Lonnie, Jason said. Call Lonnie.

He had no time to say more. The water leaped to his waist.

He heard his father’s voice from out on deck: Get out the cabin, Jason!

A thought intruded: the life jackets. There were two aboard, stashed in a storage space in the boat’s nose. Jason took two steps that way, spotted one jacket, reached for it. But just then the water jumped chest high, and the PFD slipped from his grasp. He felt around for it under the water, found a strap, pulled the vest close.

His father again: Get out the cabin!

Jason turned for the door. His first step sent him under. A floor hatch into the bilge had floated free, and he was in the hole. It took him a moment to find the hatch’s edge. He clambered back on deck, pushed for the door. In a second, no more—not even time to take a breath—water filled the cabin to the overhead.

Billy Brown was close enough to Crisfield to use his phone, and his call came into the Tangier Oil Company, a.k.a. “the oil dock.” A combination fuel pier and marine supply store on the island’s waterfront, it served as a clubhouse where watermen gathered after work to chew over crabs, boats, the weather, and wrongheaded state fishing regulations. On this afternoon, they’d come and gone—only one crabber was on hand when Sandra Parks, working the counter, heard Billy’s report that the Henrietta C. was in trouble.

By midmorning, the wind was blowing 25 to 30. It had a lot of fetch before reaching the Henrietta C.

That crabber was Andy Parks, one of Ed’s closest friends. When Sandra told him what Billy had said, Andy was alarmed: If an experienced captain like Ed Charnock calls for help, you know he’s already done all he can do for himself. The situation had to be very bad indeed.

Andy grabbed the phone and called Ed’s daughter Kelly. Listen, your dad’s boat is taking on water, he told her. Is Paul home? Yes, she replied. Her husband, Paul Wheatley, the crabber who’d exchanged waves with Ed and Jason earlier in the day, had just come in from his boat.

Tell Paul he has to go back out, Andy said. He’s got to go help your dad. Andy’s voice was cracking. Kelly had never heard him so agitated. She thought he might be crying.

Down in the boat stalls lining Tangier’s harbor, Freddie Wheatley, first cousin to Paul, was about to step off his boat, the Cynthia Lou, when Jason’s call to Billy Brown came over the radio. He heard Jason’s plea for help, and he could hear Ed’s voice in the background. He was shouting, It’ll soon be too late!

Freddie yelled over to Dean Dise, who was tidying up his own boat in the next slip. Eddie Jacks is going down, he said. Without further discussion, both men started their engines and threw off their lines.

Minutes later, Paul Wheatley and his son Jonathon arrived at the Elizabeth Kelly. They fired it up and headed out. Word reached Tangiermen aboard other boats around the harbor and they pulled out, too. Meanwhile, news of the emergency was spreading by landline among the island’s 210 households.

It didn’t reach Lonnie Moore. Exhausted after eight hours of crabbing in Pocomoke Sound, Jason’s father-in-law had changed into pajamas and fallen asleep on his sofa, the ringer on the house phone switched off.

Springtime has always been rife with hazard for the watermen of the Chesapeake. The season lacks the abrupt violence of summer squalls, full of lightning and waterspouts, but many a March and April morning speaks of wind. The seas can build high. The water runs cold.

In conditions so unforgiving, minor problems cascade into major threats and can get away from the most experienced captains. “I’ll be fine out there, even in six- or seven-foot seas, as long as everything works the way it’s supposed to,” Tangier skipper Tommy Eskridge once put it. “But if my engine cuts out, or my rudder breaks, that changes all the rules.”

So it was that veteran Tangier waterman Harry Smith Parks died one night in April 1989, after reporting engine trouble in his boat while motoring up the bay. Likewise, a fierce March 2005 nor’wester claimed James Donald “Donnie” Crockett, a Tangierman who’d spent more than half a century on the water. Crockett left Crisfield in blinding snow and spray that turned to ice on every surface of his boat. Not far out, he disappeared without a trace.

As of April 2017, one living Tangierman more than any other could speak to the dangers of spring weather. Lonnie Moore, alone on his boat one day in April 1991, was underway at a good clip when he went to check something aft, tripped, and plunged head-first over the stern.

Tide and wind propelled him southward, toward the bay’s junction with the Atlantic. Numbed and befuddled by the cold, losing strength by the minute as he treaded water, he had no choice but to go with it. For two hours he drifted, until, hallucinating and unable to move his arms, he surrendered himself to death.

Then, in an occurrence that defied all odds, two Tangiermen making a surreptitious beer run to Crisfield happened to notice something afloat in the rough water, and swung around for a closer look.

On Tangier, Ed’s daughter Kelly, frantic to reach her younger sister Danielle, found her at the Tangier Combined School, where she was filling in as a substitute teacher. Jason’s wife, Loni Renee, also worked there, teaching special ed. Soon after Kelly spoke to the office, just before 2 P.M., the principal pulled Loni Renee out of class.

She greeted the news calmly. The Henrietta C. took on water all the time, and her husband and father-in-law knew how to deal with it. Between them they had 75 years on the water. They’d be fine.

Then she heard that no one had been able to raise the boat by radio and that the bay was in chaos. Her calm turned to worry, then dread, and finally panic. Unable to reach her father by phone, she sprinted the 250 yards to her parents’ house. By the time she burst into the room where Lonnie lay sleeping, she was winded and crying. Dad, she told him, Jason’s boat is sinking. You have to go out and look for him.

Lonnie was up off the sofa, throwing on his clothes, firing questions. Where were they? How much water was aboard? His daughter knew nothing, but Lonnie, like Andy Parks, had to assume the worst. He was out the door before Loni Renee caught her breath, running for his boat. Bring Jason home to me, she called after him. Please.

The Alona Rahab was tied up at the end of a long, curving dock. Lonnie had just reached it when Michael Parks, a bearish tugboater and the island’s volunteer fire chief, yelled to him from one dock over: You want me to get a pump from the firehouse?

No time for that, Lonnie hollered back.

Do you need help?

Yes, Lonnie said. Come on.

Michael leaped aboard as Lonnie started the boat’s diesel, threw off the lines. The Alona Rahab tore down the channel, nose high, and ran full throttle past the island’s western edge and into the storm.

Jason Charnock was underwater. More than anything he felt surprise: How could this have happened so fast? How could it be happening at all? He hoisted himself past the doorframe, kicked clear of the wreck, and broke the surface. His father was treading water a few feet away, thin hair plastered to his balding head.

The Henrietta C. was standing up on its tail, about four feet of its bow rising from the water, suspended there by air trapped in its forepeak. Jason was dumbfounded by the sight, shocked by the cold, unable to move. His father snapped him out of his stupor. Come on, Ed yelled, and he led the way, swimming to the boat. They crawled onto the cowl beneath the front windows, searching for handholds. Ed latched on to the bowline. Jason wrapped an arm around the stem.

The boat’s topside faced east, flat to the wind. Both men wore what amounted to a cool-weather uniform for Chesapeake watermen, who have not adopted the wools and polyesters favored by modern outdoorsmen—cotton blue jeans, cotton socks, cotton underwear, cotton shirts. Ed wore an additional layer, a cotton sweatshirt. The air temperature was about 55 degrees, the water about 60. The Charnocks were soaked, and there was no way to gain cover from gusts that tore at them and doused them with spray, and from great wind-driven waves that crashed in, pounding them against the wooden decking. Hold on, Jason, Ed shouted over their roar. He put an arm around his son, pulled him close.

Lord, it was cold. Jason had never felt so cold. His wet hair, trimmed short, was like ice against his scalp. His neck and arms and hands ached. His shirt clung sopping to his back, and with each gust he was nearly robbed of breath. I ain’t going to be able to take this, his father said. A while later, he said it again.

Six miles from the nearest land, the Henrietta C. bobbed with the waves, and as it dropped into troughs a heavy, shuddering thud ran through the boat. I think she’s hitting bottom, Ed said.

They were in 40 feet of water. The stern was bouncing off the mud and sand on the bay’s floor. Every time it hit, a little air would burp from the boat’s nose, and the vessel would settle an inch or two lower. The water covered its front windows now and, with each thump, crept higher up their legs.

Lonnie Moore pushed into the storm at 20 knots, about as fast as his boat could manage in the heavy seas west of the island. At 32 feet, his Alona Rahab was among the smallest workboats in the Tangier fleet and could almost fit inside the Henrietta C. But it was a light and speedy craft, built sturdy of fiberglass. He had named it for two of his four grandchildren. Jason’s daughters.

Lonnie employed two mates to help fish up his pots, and their oilskins and rain jackets were piled in the cabin. Get this gear on, he told Michael Parks. I’m going to stay to the wheel, and I’ll need you out on deck to get a view of whatever you can.

They joined a growing armada of Tangier boats searching for the Henrietta C. Within a half hour of Jason’s radio call, 20 boats tossed their way westward. Most had two or three men aboard. One had five. They ventured into a storm that, for all they knew, had already claimed one of the most experienced and capable captains among them.

The men set out with only guesses as to where the Henrietta C. might be found. Eddie Jacks, like most Tangier crabbers, had not fitted his boat with an emergency position-indicating radio beacon, or EPIRB, a device that automatically sends a satellite signal when a boat is in distress and pinpoints its location for rescuers. Big commercial fishing vessels plying the open ocean are required to have an EPIRB aboard. Not so the small deadrises on the Chesapeake, and Tangiermen are disinclined to spend the few hundred dollars they cost.

If you think it’s rough there, Jason radioed, you ought to see how nasty it is over this way.

The bay west of Tangier, immense on any day, seemed even bigger in the wind and high seas of that afternoon. Freddie Wheatley and Dean Dise, knowing that Ed had been fishing pots far to the southwest—and figuring that he was inbound from there when he ran into trouble—made for the spar, a buoy out toward the San Marcos wreck. Several more boats headed that way, too. Others ran blindly for points north of the San Marcos, informed by little more than instinct.

Lonnie Moore, meanwhile, replayed his last radio conversation with Jason in his head. He knew the Henrietta C. was homebound when it started taking on water. He knew that Jason turned the boat solid to the wind. With the gale coming from the east-northeast, that meant he had tracked northwest. The time between their conversation and Jason’s call to Billy Brown had been—what, an hour? Eddie Jacks and Jason could have covered miles in that time.

The Henrietta C. was a good five miles to the northwest of the San Marcos, Lonnie decided. It was likely up near what Tangiermen call the corn buoy, about six miles west-southwest of the island. So called because it was planted near a spot where a barge full of corn had gone down, decades in the past.

He steered the Alona Rahab that way.

Back home, Kelly phoned Annette Charnock. Daddy and Jason are taking on water, she told Ed’s wife. They might be sinking. Annette’s first reaction was much like Loni Renee’s. They’ll be fine, she told Kelly. Even if the boat was taking on water, this late in the day it was bound to be close to home.

No, Kelly told her. It’s bad. It’s real bad. She told her stepmother all she’d heard. Lord, Annette whispered.

Danielle arrived at Kelly’s house, and the sisters rode their bikes up the island’s narrow main road to their father’s place, where they sat with Annette and fretted. Kelly placed a call to one of Tangier’s two state marine policemen, asking that he notify the Coast Guard. When the women stepped outside, the wind was blowing hard. A crowd had gathered up the road—islanders with their own men out in the storm, too agitated to wait for them at home. They were huddled in the chill beside the bait dock, where they would see the boats as they returned.

After a while, Kelly walked up that way, which took her past Lonnie’s house. His golden retriever, Progger, was in the yard. The dog rarely barked, but as Kelly passed, Progger threw back her head and howled.

The Henrietta C.’s bow continued to slip into the water. Ed and Jason rode it down. Look for a helicopter, Ed told his son. That’s our only hope. Keep looking for a helicopter.

They saw no helicopter or boats. They could see little at all, except seas that seemed to defy every norm. The tide was outbound, running with the wind, but waves seemed to be raging every direction at once. They collided in fizzing geysers, parted to open deep holes, and ambushed the men from all sides. Heavy tongues of water sledged them, loosening their grip on the boat and each other. With every passing minute, their wet clothes leached more of their heat and strength.

You better get right with the Lord, Ed told Jason. Call unto the Lord, because he’s the only one who can get us out of this situation.

A while later, as Ed looked to the east, he said: I don’t guess nobody’s a-coming.

A little after that he said: I didn’t think I would go like this.

Then: I’m scared.

Jason realized that his father was crying. He was too stupefied to do so himself. A blank. None of this seemed real. And the cold was so intense that it erased any but the simplest, lizard-brain thoughts. The bow was almost submerged, the water up to their chests, and Jason remembered that he still had the life jacket, draped over his arm. He released his hold on the stem long enough to hand it to Ed. A wave ripped the vest from his father’s grasp and carried it away.

Forty-five minutes after the men took hold of the bow, the last few inches of the Henrietta C. slipped under. Treading water now, untethered in the chop, they were almost immediately torn in different directions. Eighty feet of water opened between them. Across the divide, Jason could see his father staring at him.

An hour after Jason’s call to Billy Brown, the Alona Rahab and several other Tangier boats converged on the corn buoy. Pressing farther to the northwest, they came upon a debris field floating on the water—the big plywood lid from a workboat’s engine box, empty bushel baskets, others still full of crabs, and a tote labeled with Ed Charnock’s name.

So they weren’t looking for a boat, Lonnie realized, but for two men in the water. As the searchers split up, he began to appreciate just how high the seas were running. Five to six feet now, and there was no flow to the waves—they were crazed, anarchic, running every direction.

Lonnie saw that wind and tide were carrying the debris to the southwest, and fast. He pressed the Man Overboard button on his GPS console. It would enable him to cover the surrounding water in loops, always returning to the same spot to start again. He knew, from his own close call in 1991, that a man treading water doesn’t drift as quickly as flotsam. That meant that Ed and Jason were likely upwind of the debris. He turned to the northeast. Out on deck, Michael Parks climbed onto the engine box. The Alona Rahab was tossing like a cork, but the big firefighter somehow kept his feet—surfing, in effect, while he scanned the surrounding water.

Lonnie ran up the debris field until it ended, then circled back to the point he’d marked on his GPS. By this time, a Coast Guard rescue helicopter had flown the 90 miles up from Elizabeth City, North Carolina, and another Tangier waterman was on the radio with its crew. Get him to find the debris field, and fly against its flow, Lonnie told the waterman. Ed and Jason, they’re going to be lagging behind the debris.

Lonnie made another looping search to the northeast. Light and lively as his boat was, the deck swerved, dipped, and tilted under his feet, and the storm was strengthening—he reckoned it was blowing 35 now, gusting to 40. Tangier boats had fanned out to the north and south of him, and he could see them tossing. The Coast Guard chopper roared low overhead, circling. Lonnie’s wife, Carol, hailed him on the radio from back home—like many Tangier families, the Moores kept a two-way in their house.

Lonnie, do you see anything? she asked.

Nothing yet, Carol.

Do you have hope?

He didn’t answer. As the chopper made another pass, a terrible thought began to grow. He might have to tell his daughter that he couldn’t find her husband. That his four grandchildren had lost their father. He did not share his worry with the other boats. To the contrary, as he made another circle in the Alona Rahab, and another, always returning to that spot he’d marked on his GPS, Lonnie tried to encourage their crews. I know they can still be alive, he said into his radio. I know because I’ve been there.

Ninety minutes had passed since Jason’s call to Billy. Carol called again. Anything yet, Lonnie?

Nothing yet, Carol.

He made another circle, and suddenly Michael shouted, I see something! From his unsteady perch he was peering over the cabin at the water ahead of the boat. It’s right smack over your bow! Lonnie turned the wheel as Michael yelled, I think it’s Jason!

Dead ahead the waves had parted to reveal a man neck-deep in the water. He’d stripped off a pale red T-shirt and was waving it over his head. Michael heaved a life ring to him and pulled him to the Alona Rahab. He came up ghostly pale, almost blue.

Which way is your dad? Lonnie asked him, looking around.

Jason was trembling, barely coherent. I don’t think Dad made it, he said.

The Coast Guard the next morning.

Two nights later, when Pastor John Flood opened the Wednesday evening service at Swain Memorial, no sign of Ed Charnock had been found. “Dear Heavenly Father,” he prayed, “as we gather together as your people this evening, we are hurting. And Father, we’re trying to comprehend everything that has happened this week.”

Swain Memorial is the centerpiece of Tangier life, the repository of collective memories spanning more than a century—christenings, graduations, marriages, and funerals; prayers as babies were born and neighbors ailed; celebration and grief across generations. The sanctuary’s high ceiling and walls are sheathed in stamped tin overpainted in ivory, its interior illuminated by immense stained-glass windows.

It is more church than the island needs, built when the population was more than twice what it is today. Tangier is also eroding from within, its young people moving away after graduation for the opportunities, and relative ease, of life on the mainland.

Flood paced the altar. “You have to wonder, where is God in all this? What happened here?” He gazed at his congregation. “I found out that there were two blessings right immediately. That Ed, in that crisis time, in that stormy sea, hanging on, he told his son: ‘This don’t look good. You have to get right with the Lord. You need to accept him as your savior right now.’ And then Loni Renee told me that she made a deal. She said, ‘God, if you will only bring Jason home safe, I’ll serve you the rest of my life.’ ”

With that the preacher outlined how the island would process the tragedy. That Ed was a Christian mitigated the pain of his loss. That his death led Jason and Loni Renee to salvation was cause for rejoicing.

Left unaddressed was a remarkable element of that Monday: that 50-some of Ed’s neighbors and kin had risked their lives trying to rescue him. That they’d done it without pause and hadn’t much talked about it after. That this dying island is a place apart.

The entire congregation stood and, holding hands, formed a circle. It enclosed most of the sanctuary. Marlene McCready, wife of a boat captain, offered a prayer. “Please, Lord, watch over our watermen, our men who make their living on this great big bay, and protect them,” she said.

“And Lord, if it is your will, please bring Ed’s body back to his family.”

In the days that followed, the weather turned balmy as islanders searched for Eddie Jacks by air and sea. Beneath a Cessna circling southwest of the corn buoy, the vastness of the Chesapeake glittered benignly. The spotters saw nothing but water. Forty-odd islanders on 15 workboats spent days dragging the bottom but pulled up only algae and sea grapes. Finding the body preoccupied everybody. Without it, Ed’s family and friends were in limbo, unable to commence the public rituals that attend death, unable to get on with the private phase of their grief.

Twenty boats ventured into a storm that, for all they knew, had already claimed one of the most experienced and capable captains among them.

A week passed with no sign, but it did bring one form of closure. Four days after the sinking, a young islander named Thomas Reed Eskridge dived on the Henrietta C.

The boat had been surprisingly easy to locate. Shortly after it went down, a Tangier waterman came upon an oil slick and marked the location on his GPS. Another islander ventured to the spot and scanned the bottom with sonar. It showed the boat in profile, 38 feet down. Now came Thomas Reed, 20 years old and trained as a commercial diver, descending by umbilical to the bay’s floor.

It was black as pitch down there. He didn’t see the boat until he was within ten feet of its starboard side. From stem to stern, it was without a blemish. The deadrise was sitting upright, so Thomas Reed vaulted its gunwales and walked up its deck to the cabin. Inside it appeared much as it had been. “Christ Our Pilot” framed on the bulkhead. The throttle wide open. He found Ed’s keys and pried a big domed compass from its mount. He would take those to Annette.

He climbed back over the rail and walked the length of the port side. The boat was fine at the stern, solid amidships. But farther on, up under the cabin, Thomas Reed found a crack—a broken seam where several boards forming the bottom had been pulled loose by their nails. He squatted to eye the hull beneath the crack and was surprised to find an enormous hole. Six or seven boards, each 7.5 inches wide, were staved in—still nailed in place at their ends, but cracked in their middles and shoved inward. Some of the boards had snapped outright. He panned a video camera over the damage, and in its light the broken planks revealed themselves in cross-section. They were honeycombed, more air than wood, chewed hollow by worms.

What had brought down the Henrietta C. was no longer a mystery. The wonder was that it had lasted as long as it had.

Eddie Jacks came up ten days after the sinking, not far from the boat he’d followed to the bottom. His remains went to a mainland medical examiner first, then to a funeral home. It wasn’t until May 17, 23 days after he’d left the island, that the mail boat brought his closed casket back to Tangier. The town ambulance carried it to Swain Memorial.

That afternoon a half-dozen old-timers met for their daily coffee klatch in a tile-lined room of Tangier’s defunct health center. “Ol’ Ed’s gonna be missed,” said Leon McMann, at 86 Tangier’s oldest active waterman.

“I’ll tell you something else about him.” This from Jerry Frank Pruitt, the boat builder, who in 70 years had never lived more than 400 feet from Ed. “There weren’t no more honest a man in all the world.”

“That he was,” Richard Pruitt murmured.

Then Jerry Frank broached a subject that had been the stuff of island rumor. “About four year ago,” he said, Ed pulled the Henrietta C. out of the water at the boatyard, and “they found a place in the bilge, up under the cabin, where the wood was eaten with worms. Not the kind you get overboard, but the kind that get in trees, that kill trees.”

“A dry woodworm,” Jerry Frank called it. Park your boat or a piece of onboard gear under the trees and the worms would drop in. They ate a boat from the inside out. He suspected they came from trees in Reedville, on the bay’s western shore, where Tangiermen had been known to store equipment.

“I’ve taken them out of quite a few boats around here,” he said later. “They’re hard to see. That hole’s so small you’d better look very close. The worm gets bigger as he eats. When he first goes in, he’s a little thing.” The boatyard might not have noticed the infestation, except that the affected boards wouldn’t hold paint, he said. Repairmen scraped out the damage, filled, and painted, and told Ed he’d need to swap out the wood.

Ed had loved that boat. He’d been a stickler for maintenance. He’d replaced several boards since, at the starboard stern where he fished up his pots, a high-wear region of the hull. The previous November he’d had the Henrietta C. in a Smith Island boatyard, getting the hull sanded and filled and painted, zinc applied to its rudder and prop shaft, a new seat installed in the cabin.

But in that and several other repairs, he had not replaced that weakened section of the bottom. The work would have kept the boat

out of the water. Would have kept the Charnocks from working.

He and Jason had gone out last April 24, a punishing day, and likely cracked one of those worm-tunneled boards early in the run home. And after one went, so did another, and another, like a zipper pulled.

So it happened that 24 days after the sinking, all of Tangier crowded into Swain Memorial for Ed’s funeral. His casket was up in front of the altar, flanked by glass-shaded torchères, surrounded by flower arrangements. One, four feet long, was in the shape of the Henrietta C.

Ed’s son-in-law, Denny Crockett, delivered the eulogy. He talked about how Ed, quiet though he was, could tell a good story down at the oil dock. How he’d get everyone laughing by casting himself as the butt of those stories. How he’d paint himself as destitute, courting starvation, when all in the room knew he was among the most successful captains around.

Denny didn’t mention it, but Eddie Jacks was also known to lament the state of the Henrietta C. in those conversations.

“That boat is going to be the death of me,” he’d tell his fellow watermen.

He meant that keeping a wooden boat is an expensive proposition, that he had to pour money into it.

He meant it as a joke.

Earl Swift () is the author of the forthcoming . He is a fellow of Virginia Humanities at the University of Virginia.