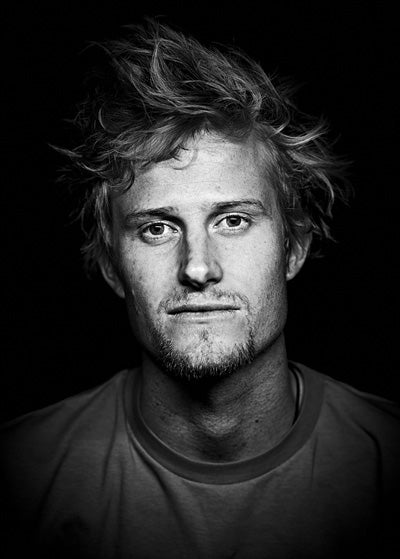

By now, you've heard all about and his film Cold, which won big awards at , , and a handful of other festivals. What you may not have heard is that Cory Richards got his start in fashion photography, and that he used what he learned shooting models to shoot a personal project on the people of Nepal and Tibet. He calls it his “” project. We asked him about his portrait series in the interview below. Click here to see a gallery.��

–Amy Silverman

Since you’ve talked about Cold a lot we’re going to skip that and go directly to your other work.

Yeah. I am so happy about that. You have no idea.

I love your facial landscapes project.�� How did those images come about?

It’s funny because all that comes from, believe it or not, a commercial fashion background. I worked in commercial fashion on these shoots that were super scripted and organized. You come out, you go into a motor home in the morning, you talk to the models, you talk to the photographer (back then I was the assistant), and then you go and execute the shoot—trying to sort of play off people’s insecurities. To me the whole project stems from the idea that there’s so much more inherent beauty that we don’t really look at all the time, and one of the places you often see that is in the elderly. They have this massive amount of life experience and in our modern culture we remove all the wrinkles and don’t like looking at them. For me, having looked at so many faces that were kind of polished with make up and all this shit, I was like, there’s something more real about this beauty. That’s where it came from. I went to Nepal and Tibet and just started looking for the people who had worked the hardest, who had lived the most, and then I just applied very simple commercial fashion lighting to the shoots and it turned out beautifully. I’m like, “Oh god, I can like count his whiskers,” which is not necessarily a bad thing. You can get into it with the person. The other thing about the project is that I kind of wanted to celebrate the people who climbing success was built on—sherpas and the local people that support and provide the infrastructure.

Why are some of them in color and some in black and white?

That’s such a good question because it’s almost like a non-decision. It just is natural. When I’m looking at the images I sort of have it in mind that this is going to be black and white or color.

Do you do any retouching?

I do processing. I never take anything out. If anything, I amplify things. I do some burning and dodging. One of my favorite bodies of work is Avedon’s . If you look at his printing proofs, it’s incredible to see where he chose to burn and dodge, to make things darker, to accentuate things. All of that goes into my images, and so the black and whites are very much taken from a darkroom approach. It just so happens that it’s a digital darkroom now.

Do you show the people the photos?

We took a little Canon printer. We’d shoot them with the printer set up, and we could just make a print and hand it to them right away.

What did they think?

There was a lot of laughter. There were a lot of people that didn’t want to look at the pictures, but above all else it was a tremendous amount of fun. People always have fun when we do that because they laugh at each other. They also get something out of it. It’s not just being in front of a camera, which is such a foreign thing to them.

How did you end up doing fashion?

I always wanted to be in photography. One of the ways to learn and to make money and to sort of sponge when you are younger is to assist people. So I got hooked up with this catalog fashion and high fashion photographer, Bill Cannon, in Seattle. It was just a way for me to immerse myself in photography and make money to fund my next climbing trip. That’s how I got into it, and then I shot on my own because naturally you assist long enough and then people start to ask you to shoot it. And you know, it’s fun. It’s an extreme. It’s totally different. Everything is laid out for you and then you have this execution that’s expected. So you really have to step up to that level—versus doing your own personal project like a facial landscape where there is no pressure aside from yourself. I like that pressure. I like having to deliver.

How did you pick up the camera?

I was a high school drop out, but I was always into visual arts. I think the arts are what carried me through a really dark period when I didn’t have a lot of direction as to what I was going to do. When I got back into climbing it became sort of obvious to me that photography was a way for me to translate those stories and continue to be immersed in some sort of visual art. So I started traveling and shooting when I was 18 or 19, and then I ended up studying abroad in university in Salzburg Austria. I had a photography instructor named Andrew Phelps, and he thought I should pursue it more seriously. I sort of branded myself as a “professional” photographer when I was 19, which I was anything but. I was so far from professional anything. I’m still pretty far from professional anything. But people are like, “How long have you been shooting professionally?” If I want to give them a big number, I’m like, “Well I’ve been shooting professionally 11 years now.” I feel like every day I’m pretty lucky to be able to say that. I just wanted to do it, because climbing is such a great platform for telling the story of human potential and struggle. It’s a great place to tell a story. And I think if you can observe it in that environment it becomes easier to recognize in more subtle environments.

When you are on an expedition do you think of yourself more as a photographer or climber?

I get that question a lot and I think I’ve never thought of myself as one or the other. It’s not one or the other. I think that photography helps separate you from brutal experiences. I think the camera is a useful psychological tool when things are going really, really haywire. If you are observing it and working on photographing it, there’s a barrier. It’s like a safe wall. It removes you from the immediacy of the experience and allows you to be an observer. I’m not sure if that’s a good or a bad thing, but I certainly think it acts as a firewall in certain situations. It’s interesting, because then you are left with these images you are almost trying to put yourself back into to try and understand what that experience was like.

When you come back from trip how do you approach editing?

Well, I did a story recently and it was over three months, two different trips, and I had 65,000 images, and I didn’t edit it.

You just sent 65,000 images to National Geographic?

Yeah.

That’s what they like though, right?

Yeah. If I’m doing it for say, you guys, I try to have a rolling edit always because you know when the images are good. You come back every day. You edit. You do a very loose, rough edit. You mark them and then at the end of the trip you’ve got basically a loose edit to begin with, and then you can go through and refine it. Depending on the guidelines of the various clients—be it an editorial publication or something that gives you more creative license—I’ll apply whatever treatment I need to afterwards. If I go and shoot something for a magazine, anywhere from a hundred fifty to three hundred images as a final edit is pretty reasonable. You are only going to have maybe 12 to 15 images published at the most for any given story.

Who do you look at for inspiration?

Obviously in my own genre, I’ve watched people like for a really long time. I really look to Jimmy for an overall business model, and there are certainly pieces of his work that I admire tremendously. When it comes to classic storytelling, and are sort of like my editorial heroes. They are amazing. When I’m thinking about portraiture, Avedon is, in my opinion, one of the greatest portrait artists in any medium. He’s incredible. There’s so many. and are it as far as wildlife photographers

Are you excited about making films too?

Absolutely. But one of the things I won’t try to do is put out a film every year. It has to be something meaningful and important to me that I approach quietly and with intent. So I just want to go into it with some sort of calculated measure.

It seems like these days most people expect that you will be shooting moving images as well as stills on assignments?

Yeah and I think there’s some push back that’s important on the side of the photographer. I think you have to be realistic with people and say, “Yeah I can shoot both but that doesn’t mean both will be—They aren’t going to be as good as they would be if I were just shooting one or the other.” I think that’s really important, and I think photographers and videographers have to stand up for themselves in that regard when a client asks them to do both. Say, “This is what I am capable of.” Be honest with yourself, because some photographers are going to be able to do more than others and that’s ok. Just be honest and don’t overpromise. I think you should always have a policy of under promising and over delivering. That’s the way you want to go.

It is kind of crazy that in Cold you shot that video and that great still right after the avalanche.

But it’s a situation where you have time to think. Like I was talking about earlier—about the camera working as a firewall—I felt that raw emotion coming on and I turned the camera on myself in an attempt to step away from what I was feeling. Even though I was obviously viscerally engaged in that emotion, I was trying to create some sort of space between myself and the emotion. Whether that worked or not, I’m still in therapy [laughing]. You also realize at the time, if this is important for video then it’s almost certainly important for a still too. So as soon as I was ready, I just cranked off a couple frames there.

What’s next for you?

My next project is the West Ridge of Everest with r. It’s the American Route. It goes up the West Ridge and up on the North Face. It’s been done once—by —but it’s never been repeated.