Depending on which direction you look, the taxiing strip at northern Maine’s tiny Millinocket Municipal Airport is either New England’s most blighted runway or its most picturesque. Out the left-hand window of an accelerating Cessna, I see the twin smoke-stacks of an abandoned paper mill surrounded by chain-link fences and corroding storage tanks. To the right is the cambered whaleback of Mount Katahdin breaching up from the green swells of the Maine highlands. It’s like watching establishing shots for two different documentaries: on the right, a soaring, Planet Earth–style aerial; on the left, an image from Roger & Me.

“Look down there,” says a voice in my headset. “You’ll see some clear-cuts, but mostly it’s been thinned pretty sparingly.” The voice belongs to Mark Leathers, a 53-year-old forester who manages the 74,000-acre woodland parcel spread out before us. We’re just east of Katahdin now, looking down at a seemingly untouched playground of wooded foothills and trout streams tumbling off the mountains to the west. The most dramatic of these is the East Branch of the Penobscot River. Leathers, perched in the plane’s front seat, points out a few burly-looking Class IV whitewater runs. If he and his boss, conservationist and Burt’s Bees cofounder Roxanne Quimby, have their way, this wilderness will be America’s next national park.

Suddenly, the Cessna takes a hard 45-degree tilt. “Check out the moose,” yells Leathers. Sure enough, there’s a cow wading in an oxbow pond below, head down, seemingly oblivious to the drone of our engine.

Technically, this Idaho-shaped chunk of land, which contains a 30-mile stretch of the International Appalachian Trail, is known as the East Branch Sanctuary. But around Millinocket it’s simply referred to as “Quimby’s land.” The self-made millionaire owns it, along with 119,000 acres of other timber-company lands that she started buying up back in 2000, when Burt’s Bees was raking in about $23 million a year. Her plan was to give the property to the National Park Service, thereby galvanizing other donations that would eventually establish a 3.2-million-acre wilderness in the last great undeveloped region east of the Rockies.

But the campaign stalled out of the gate. Public land is a tough sell in northern Maine, where residents are accustomed to hunting, fishing, snowmobiling, and cutting timber. Many didn’t cotton to the rhetoric of a wealthy environmentalist; others feared that the proposed park would spell the end of the region’s struggling paper mills. The fact that Quimby first partnered with a Massachusetts conservation non-profit called Restore didn’t help matters. She’d managed to align herself with the three groups viewed most skeptically in northern Maine: enviros, the federal government, and Massholes.

But a dozen years and a few hundred Ban Roxanne bumper stickers later, Quimby is back with more practical ambitions. Last spring she announced plans for a dramatically reduced 74,000-acre Maine Woods National Park just east of Katahdin, carved entirely from her own property. And thanks to better diplomacy and a new emphasis on economic benefit, Quimby is beginning to win hearts and minds. In the past two years, the region’s chamber of commerce has come on board, and snowmobile clubs, logging operations, and other former opponents have lined up to endorse a special resource study—an essential precursor to the park. Alexander Brash, northeast regional director of the National Parks Conservation Association, calls the rebooted park “a realistic expectation,” pointing to polls that show solid majorities of Mainers now willing to entertain the idea.

“People in northern Maine like living in the woods,” says Quimby. “They like to fish and hunt and hike. But they don’t see conservation as an abstract concept that needs protection. That’s not important to them. What’s important is jobs.” And in the past decade, unemployment in the Katahdin region has fluctuated between eight and 28 percent.

“I’ve had a lot of experience creating economic prosperity,” she continues. “Now people in this region need that, so it’s a better story than, you know, ‘Let’s save habitat.’ ”

Quimby's connection to northern Maine dates to the mid-'70s, when she spent a decade living in a cabin and waiting tables before launching Burt’s Bees. The daughter of an engineer and a stay-at-home mom, she was born in Massachusetts and headed west in 1969 to attend the San Francisco Art Institute. California’s back-to-the-land movement soon got under her skin. In 1974, armed with a bachelor’s degree, a microbus, and a few tattered issues of Mother Earth News, she and a boyfriend drove cross-country in search of a homestead. They landed near Dover-Foxcroft, Maine, where they bought 20 acres for $3,000. Quimby was still living in her cabin 10 years later—with twin children but without plumbing, electricity, or the boyfriend—when she met a beekeeper named Burt Shavitz. The pair went into the beeswax business, selling soap at craft fairs and, eventually, Manhattan boutiques. In 1991, Quimby concocted a recipe for lip balm, and within two years Burt’s Bees was moving into an 18,000-square-foot headquarters in tax-friendly North Carolina. Clorox paid $913 million for the company in 2007.

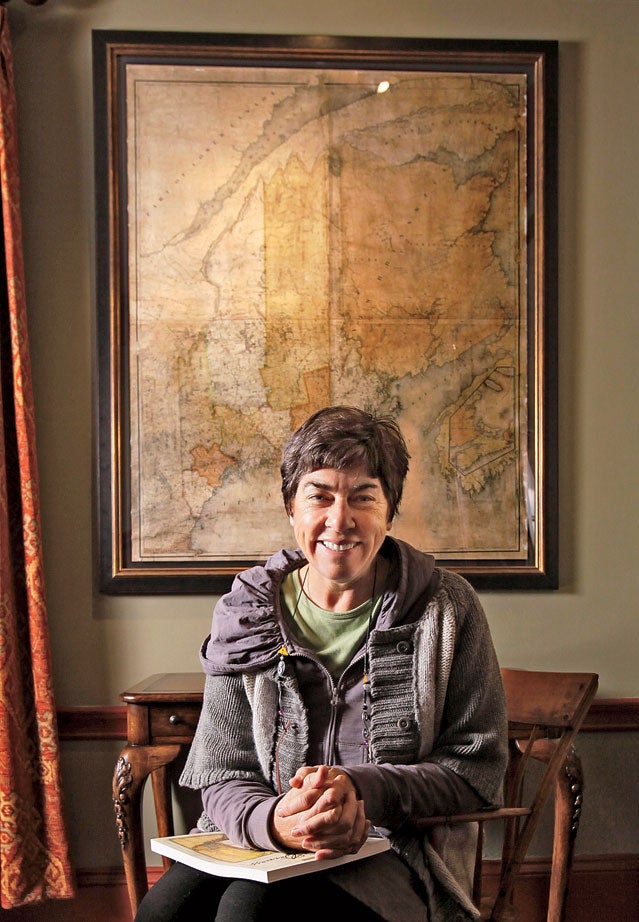

Quimby, now 61, tells me about her rise while seated in the dining room of her tasteful colonial home in Portland. She smiles easily, but her speech is boardroom deliberate and sprinkled with business jargon. “Roxanne’s casual appearance and style can lead others to underestimate the power of her insights and impact,” says former Burt’s Bees CEO John Replogle, now the chief executive at eco-products titan Seventh Generation. “She’s extremely adept in the boardroom.” Despite her intent to donate the property, Quimby refers to her woodland holdings as “investments.” The returns, she explains, will be “accumulated by future generations.”

If she were motivated by conservation alone, a donation to, say, the Nature Conservancy would be a lot easier than the proposed park. Quimby, however, wants her land to attract visitors—lots of them. She feels a deep kinship with George Dorr, who devoted his fortune to help establish Acadia National Park in the early 20th century, and is an admirer of author Richard Louv, who coined the term nature deficit disorder to describe kids’ alienation from the outdoors.

“We have to reconnect Americans, particularly young ones, with nature,” she says. “If we don’t get people into the parks, then it doesn’t matter how much land we conserve.” In other words, the Maine woods need protection, but they also need marketing. To hear Quimby tell it, the park service is a superior brand to a big conservation group. It is also, she insists, a quintessentially democratic institution. Quimby, a dedicated liberal, argues that there are no political partisans in the backcountry—despite an election year already seething with antigovernment rhetoric. “To me, all that politics is just weather,” she says. “But our basic American values? Those are climate. And in America, we put a value on our public lands.”

If this sounds Pollyannaish, consider the numbers. Last year, some 280 million guests visited the national park system, which contains about 400 “units”—everything from parks and trails to monuments and historic sites. Tourists drop $11.3 billion each year in park gateway towns like West Yellowstone, Montana, and Bar Harbor, Maine. As Quimby says, “It’s very well documented that park service units create jobs.”

There are essentially two ways to create a national park. The first: Congress asks the National Park Service, which is run by the Department of the Interior, for a special resource study—an evaluation of a site’s worthiness. The NPS outlines the would-be park’s boundaries and budget and sends the study to Congress, which has the final say. Congress can ignore a favorable NPS analysis or even authorize a park that the service has not endorsed, as in the case of Alabama’s Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area, which was designated in 2009 before the NPS even finished its study.

The other method is for the president to confer national-monument status by executive order. This privilege was granted under the 1906 Antiquities Act, which Teddy Roosevelt used two years later to create Grand Canyon National Monument, thwarting politicians tied to logging and mining who’d opposed a national park for decades. Ever since, monument status—which focuses on preservation rather than recreation—has been both an end run around the sticky congressional process and a training-wheels program for future national parks. But it can take a while: the Grand Canyon, for example, became a park only in 1919, after the monument’s popularity and profitability gradually won over the opposition. Six new national parks have been designated in the past 20 years, most recently Colorado’s Great Sand Dunes in 2004—and most of these were already national monuments. Not since Minnesota’s Voyageurs in 1971 has a new national park been created from scratch—that is, via the large-scale acquisition of private land.

“The parks are so loved, we assume that they were handed down by a benevolent Congress,” says Dayton Duncan, writer and co-producer of the PBS series The National Parks: America’s Best Idea. “But when you start to turn over the rock of any national park, you find the opposite—that Congress is the last one to the table.”

For Quimby, the fact that it’s been 40 years since the creation of a truly new national park just means we’re overdue. But she needs a majority of Maine’s four federal legislators to adopt this view before it can go before Congress and the NPS. Only one of those members, Democratic representative Chellie Pingree, has backed the essential special resource study. Getting the rest of the delegation on board requires support from the rural north, where constituents tend to have better relations with timber companies than with government entities.

“I see the discussion about 70,000 acres of federal park as a real dangerous kind of precedent,” says Patrick Strauch, executive director of the Maine Forest Products Council, an industry lobbying organ.

Already, the post-bubble political climate has ensnared many proposed public lands in a sort of culture-war catch-22. On the one hand, the Obama administration advocates investment in parks as a step toward economic recovery. In 2009, an incoming President Obama pledged more than a billion dollars of stimulus money to the NPS. But that largesse has since dwindled, and to date the administration has added just six park units. (Bush added 12 units during his eight years in office, Clinton added 19, and Ronald Reagan, whose first interior secretary, James Watt, was vilified for his anti-conservation policies, added 17.)

“With the change of administration came a real sense of excitement,” says Duncan. “That has now collided with a new political reality in which the House is being held hostage by people who believe there is no role for government.” Opponents of the Maine Woods National Park, Duncan points out, make largely the same arguments as those who protested the Grand Canyon a century ago: “A philosophy is taking hold that’s very much in tune with the robber-baron era of the 19th century. Teddy Roosevelt came in and fought it then, but it’s the same philosophy today.”

So how do you win support for a national park when locals don’t want it and the political climate seems untenable? Quimby started by mending fences with sportsmen, offering an additional 45,000 of her acres to the state. This land, which is just south of the proposed park, would allow hunting, snowmobiling, and timber harvesting.

“I was her harshest critic, no question,” says George Smith, who served as director of the Sportsman’s Alliance of Maine from 1993 to 2010. When Quimby asked to meet with him in 2006, Smith was flabbergasted. “But she changed her approach, and she did a lot to accommodate us—designating snowmobile trails, selling back some of the land.”

Still, Quimby’s primary tactic has been to focus on potential economic perks, pointing east to Acadia, where visitor spending has helped create some 3,150 jobs. She’s pledged $40 million to get the new park off the ground—half from fundraising, half out of her own pocket. And if her timing seems poor in Washington, it couldn’t be better in northern Maine, where paper mills have been closing at an alarming rate. Last year, unemployment in the Katahdin region hovered around 22 percent.

“At what point do you decide you’d better look elsewhere?” asks Smith. “When you’ve lost a thousand jobs? Two thousand?”

Quimby has set a goal of donating the land by 2016—the Park Service’s centennial anniversary. The odds of meeting that goal seem long, but there’s no denying Quimby’s progress: endorsing a special resource study are predictable supporters like the Sierra Club and the state’s Natural Resources Council, but also the Katahdin Area Chamber of Commerce, a few snowmobile clubs, and a logging empire that’s locally renowned for its role in the Discovery Channel show American Loggers. And Quimby’s plan is certainly on the Interior Department’s radar. She’s friendly with Secretary Ken Salazar—they both sit on the board of the National Parks Foundation, which funnels private money to the parks. Last August, during a tour of the Northeast, Salazar and NPS director Jon Jarvis held an impromptu public forum in Millinocket. Salazar stressed his impartiality, but as former NPS northeast associate director Robert McIntosh tells me, “Reading the tea leaves, I don’t think Salazar would have gone to Millinocket if he wasn’t interested.”

Then, of course, there’s the presidential election. If Obama is victorious in the fall, nothing much changes, and Quimby continues lobbying for public opinion. Ironically, park supporters could benefit if Mitt Romney is elected—it would hasten the chance for an 11th-hour executive order from Obama. The truth is, national monuments are often designated during an outgoing president’s final days in office: Clinton designated seven in his last week in office, and Bush created the 95,000-square-mile Marianas Trench Marine National Monument as he departed in 2009. Quimby, however, cares little for political football. She takes the counterintuitive view that local controversy bodes well for a future park—she is, after all, fighting the same slow battle that once created Acadia and the Grand Canyon. “In 100 years,” she says, “the park will be there, and the objections will be long gone.”