On March 20, 2019, fish caught in Ohio’s Cuyahoga River were declared ��by federal environmental regulators.��It was a major milestone in the river’s recovery—once one of the most polluted waterways in the country—because 50 years earlier, it caught on fire. Public outrage around that 1969 fire spawned a national reckoning on water pollution��and led to the creation of the Clean Water Act, the Environmental Protection Agency, and Earth Day. Earlier this week, however, the Cuyahoga caught fire again. It’s a timely reminder that much of the progress made on water pollution during the past 51 years is rapidly being undone.��

The Cuyahoga’s water helped create the industries that would pollute it. Tracing a distinct U shape across northeast Ohio, the 100-mile-long river flows into Lake Erie��30 miles west of its headwaters. With a��series of rapids and waterfalls that cascaded 500 feet down��that distance before it was dammed, the Cuyahoga didn’t offer many opportunities for navigation, but its flow was just right to serve as the source of water for , which opened in 1827. The region’s deposits of coal and iron ore were made accessible by that canal, attracting big businesses like Standard Oil and Goodyear Tires.��Those��industries��would later build several dams along the route to provide hydroelectric power.��

The cities of Cleveland and Akron, located 38 miles apart along the river’s banks, boomed. And all the waste from��their industries��and residents��wound up in the Cuyahoga, whose lower reaches were transformed into an open sewer.��

“Yellowish-black rings of oil circled on its surface like grease in soup,” Czech immigrant Frantisek Vlcek��described��. “The water was yellowish, thick, full of clay, stinking of oil and sewage. Piles of rotting wood were heaped on either bank of the river, and it was all dirty and neglected.”��

That was Vlcek’s first sight of the river in the 1880s. He goes on to explain that he learned it flowed into Lake Erie, the source of Cleveland’s drinking water, as he stood outside a slaughterhouse��watching “a��great stream of dirty water rushing from it right into the river.”��

The Cuyahoga��first caught on fire in 1868��and would burn 11 more times until the blaze��on June 22, 1969. That last fire wasn’t a big one, causing just $50,000 in damage, and fire crews were able to extinguish it . In fact, it burned for such a short period of time that no photos are thought to have been taken of it.

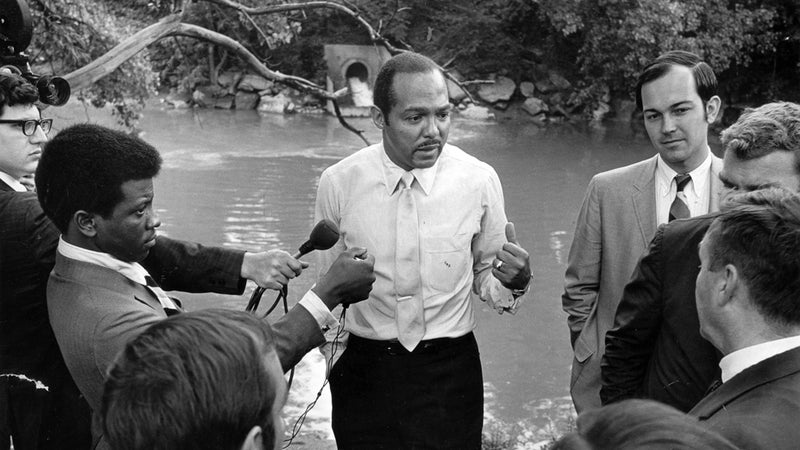

That lack of photos from the 1969 fire is particularly relevant. Just two years prior, Cleveland became the first major American city to elect a Black mayor: Carl Stokes. And one of Stokes’s��signature issues was ;��at the time of the fire, he’d just convinced��voters to pass a $100 million taxpayer-backed initiative to begin improving the quality of��the city’s waterways. But Stokes knew that no matter how hard his city—located at the river’s terminus—worked to clean up its act, the��Cuyahoga wouldn’t be a clean river until every stakeholder along its entire length participated in its rehabilitation. The fire must have seemed like the perfect opportunity to drive home the importance of that initiative, because Stokes assembled a press conference on the Cuyahoga’s banks��and made the argument that it would take cooperation from state and federal governments to effect meaningful action on Cleveland’s environmental problems. Stories that resulted from his��press conference apparently , but one did end��up in the August 1 issue of Time magazine.��

And was a big one, featuring not only a cover-story exposé on the����in Massachusetts��but also stories on the successful return of Apollo 11 astronauts to earth��after their historic mission to the moon. Lacking an accompanying image from the Cuyahoga fire in June, Time instead ran one from the river’s 1952 fire (included at the top of this article), which had been much larger, causing $1.5 million in damage (close to $15 million today), along with a list of other polluted rivers across the country. The article��described the Cuyahoga as a river that��“oozes rather than flows” and said that if a person fell into it, they would��“not drown but decay.”

Coming just seven years after the publication of Rachel Carson’s lauded��book��, and amid a��growing environmental movement, such a dramatic image reaching so many millions of eyeballs caused a real stir.��

The following January, President Richard Nixon of his State of the Union speech to the environment, saying, “The great question of the seventies��is: Shall we surrender to our surroundings, or shall we make our peace with nature and begin to make reparations for the damage we have done to our air, to our land,��and to our water?”

Later that year, Stokes was called to testify before��the Senate about Cleveland’s��water-pollution problems. By that time, the mayor had fleshed out a larger argument, connecting environmental pollution to quality-of-life and health issues in what he dubbed��“the urban environment.” And he’d begun calling for federal funding for��clean-water efforts.��Speaking in front of the Senate, , “We have the kind of air and water-pollution problems in these cities that are every bit as dangerous to the health and safety of our citizens as any intercontinental ballistic missiles that’s��so dramatically poised 5,000 miles from our country.”

Then, on April 22, 1970, in response to both the Cuyahoga fire and off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, Gaylord Nelson, a senator from Wisconsin, organized a “teach-in” protest on college campuses nationwide��to spread awareness of environmental issues. Rebranded Earth Day, 20 million Americans—10��percent of the U.S.��population at the time—.��

In response, President Nixon of an Environmental Protection Agency��to Congress. The EPA swore in its first director on December 4��and would go on to coordinate federal efforts to protect the environment.��

Stokes’s brother, Louis,��served in the House of Representatives��and was able to secure federal funding for cleanup efforts on the Cuyahoga River. That helped establish a model for revisions to an old piece of legislation, from 1948, that would eventually become known as . It was signed into law in 1972, the same year that , later becoming��an example��for state agencies that now exist nationwide.��

And the��photo of the Cuyahoga River ablaze in 1952, published by Time in 1969, came to symbolize the importance of that environmental revolution. The fire was even the subject of songs by and R.E.M.

But Stokes didn’t stop there. Rather than celebrate the success of his efforts to call attention to the ways in which wider environmental issues were impacting urban environments, he worried that the new��movement would leave inner-city residents behind. Speaking on that original Earth Day, he stated, “I am fearful that the priorities on air and water pollution may be at the expense of what the priorities of the country ought to be: proper housing, adequate food, and clothing.” is still being debated today, particularly as it relates to climate change.��

Cleaning up the Cuyahoga remains . Regulations implemented by both federal and state EPAs have stopped��the sources of pollution and have drawn state, federal, and local funding and participants. One man paddles the river in a kayak every��day��. Communities are working����to , restoring habitat for fish and other wildlife. Yet rather than symbolize how polluted our environment is, the Cuyahoga has become a poster child for the EPA’s success. Even the section of it��between Cleveland and Akron—the most polluted stretch—has met established by the Clean Water Act for its recovery.��

“This is an example of the progress that can be achieved when you collaborate and dedicate resources to improving the quality of water,” said��Ohio��governor Mike DeWine , applauding the EPA’s decision to declare fish in the river safe to eat.��

But protections for the Cuyahoga are not perfect. A major remaining source of pollution are��, which allow sewage, toxins, and fertilizer to flow into the river during heavy rains. It was through one of those that a fuel tanker after a road accident on August 25, 2020.��

Like the 1969 fire, the one this week��didn’t cause much damage��and was extinguished quickly. And like the 1969 fire, this one could serve as a warning of the peril our environment faces, because the last 51 years have not been marked only by progress.��

Late last year, the Trump administration made changes to the Clean Water Act that from 60 percent of streams in this country, along with 110 million acres of wetlands. At the same time, it restricted the ability of state governments to . Before that, it revoked a proposed rule aimed at limiting water pollution ��and eliminated an established rule . All three actions directly threaten the legacy of Carl Stokes��and that river fire back in 1969.��

Another regulatory rollback also threatens Stokes’s early work on environmental justice: by restricting public input on the federal decision-making process through the National Environmental Policy Act, the Trump administration seems to be ��to make their voices heard in decisions that impact their communities.��

“The most vulnerable communities are going to pay with lives and their health,” , vice president of environmental justice for the National Wildlife Federation, in a response to that decision. “Moving forward with this is reckless and will endanger the lives of Black and brown��communities and Indigenous communities. It’s really that simple.”

And one other major rollback, this one from the Supreme Court, also threatens Stokes’s legacy as the first Black mayor of a major American city. His role in public office came��on the heals of the 1965 Voting Rights Act (and several similar state laws enacted by Ohio around the same time), which prohibited racial discrimination in voting. However, in 2013, the Supreme Court voted to invalidate certain parts of that act, . And voter-suppression efforts ahead of this November’s election are .��

Such policies may not have caused this week’s fire on the Cuyahoga. But��by halting progress on clean water, by denying communities a voice on their own environmental protections, and by making the election of politicians like Carl Stokes more difficult, they all combine to undermine the work done in the wake of the��river’s fire 51 years ago.