Geoffrey Farrar was a highballer, a climber who would routinely take on 30-foot bouldering problems without a rope. His track record helps explain why there was confusion at first when the 69-year-old Farrar was found with a crushed skull, barely breathing, at the base of a climb at Carderock, in Maryland, not far from Washington, D.C.

Carderock crime scene: Farrar’s body was found near the tree on the left, close to the water.

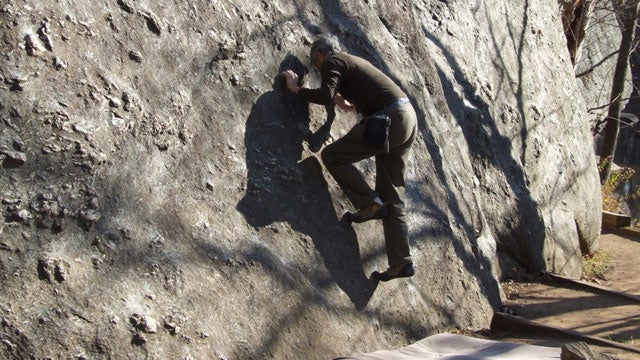

Carderock crime scene: Farrar’s body was found near the tree on the left, close to the water. DiPaolo (front) with Farrar behind him and another climber (and DiPaolo’s dog Caesar) at Carderock

DiPaolo (front) with Farrar behind him and another climber (and DiPaolo’s dog Caesar) at CarderockFarrar had taken falls before, and he had sustained significant injuries. After he died at a local hospital following the December 28 mishap, media in the Washington area initially believed the cause of death was a rock-climbing spill.

But something didnтАЩt add up to climbers and law-enforcement investigators. Farrar fell only eight feet, but there were four distinct, severe wounds to his skull and jaw, blood was spattered several feet away from where he supposedly landed, and his body was almost ten feet from the base of a popular route called CrippleтАЩs Traverse, in an improbable position for a short fall at that angle.

In addition to Farrar, there were four experienced climbers at Carderock that day: John Gregory, 63, a recognized leader among a tribe of mid-Atlantic rock climbers who show up regularly at the crag; Mark Nord, 67, another elder in this group; a 59-year-old woman who spoke to ╣·▓·│╘╣╧║┌┴╧ but asked not to be named; and David DiPaolo, a powerful 31-year-old whoтАЩd grown up climbing at Carderock and had been mentored for years by Farrar.

Based on accounts by Gregory, Nord, and the woman, suspicions immediately fell on DiPaolo, who had a reputation among Carderock climbers as an unstable hothead, a drug abuser, and a petty thief. There had been a fierce argument between Farrar and DiPaolo the day before FarrarтАЩs injury, and witnesses said it had reignited just prior to the incident. In addition, DiPaolo was seen sprinting away from the climbing area moments before Farrar was found at the base of CrippleтАЩs Traverse.

тАЬWhen I heard the facts,тАЭ says Matt Kull, one of DiPaoloтАЩs former climbing partners, тАЬI thought, ThatтАЩs what Dave is capable of.тАЭ

DiPaolo was apprehended almost two weeks later, at a traffic stop near Glen Falls, New York. During questioning, he admitted to police that he had clubbed Farrar to death with a clawhammer, but he insisted that he acted in self-defense. In DiPaoloтАЩs version of events, Farrar began choking him during a heated argument, and he saved himself by striking Farrar with a carpenterтАЩs tool that just happened to be lying on the ground near them. DiPaolo told police that he тАЬthrewтАЭ away the silver-colored, red-handled clawhammer, which was found in the Potomac on December 29.

He was charged on January 31, in U.S. District Court, with , which could result in a sentence ranging from 15 years to life. Authorities close to the case, speaking on condition that they not be named, told ╣·▓·│╘╣╧║┌┴╧ that they may upgrade the charge to murder, depending on what they find in the ongoing investigation. There are some indications that DiPaolo, whose case wonтАЩt go to trial for months, might plead guilty to avoid a potential death sentence. The key will be whether DiPaolo acted on the spur of the moment or whether the alleged killing was premeditated. If heтАЩs found guilty of the latter, he could face the death penalty.

[quote]Farrar, a curmudgeonly but mostly beloved fixture on the climbing scene for more than three decades, was as well known for mentoring troubled young men.[/quote]

While there has been extensive reporting and commentary on the incident, much of it is inaccurate and all of it is incomplete. IтАЩve been climbing at Carderock for decades; I knew both Farrar and DiPaolo, as well as many climbers who were well acquainted with both of them. This account is based on full access to the three climbers who were at the crag that day, as well as discussions with other fellow climbers, investigators, and forensics experts. There are a number of critical, as yet unreported detailsтАФsuch as where the hammer came from, the deteriorating relationship between the two men, and the findings of a secret police reenactmentтАФthat leave authorities and climbers with little doubt about what really happened.

Farrar, a curmudgeonly but mostly beloved fixture on the climbing scene for more than three decades, was as well known for mentoring troubled young men as he was for hectoring fellow climbers with unsolicited advice on routes and holds. He was an above-average climber, and over the past decade or so he focused mostly on bouldering and free soloing.

David DiPaolo was a strong climber who developed a passion for the sport from the moment his father, Vince, brought him to Carderock in his early teens. (Repeated efforts to contact Vince DiPaolo for comment on this story were unsuccessful.) David earned a rep as a young gun before his 18th birthday, and he repeatedly scaled one of the most difficult routes at Carderock, a 30-foot climb known as Silver Spot, without a rope.

But it was clear to everyone that DiPaolo, whose best friend seemed to be a wildly ungroomed dog named Caesar, had emotional issues that grew more pronounced as he aged and descended into a life of darkness, dominated by addiction to heroin, oxycodone, and cocaine. He supported his habits with some part-time construction workтАФacquaintances and authorities say he kept many tools in his vanтАФa trust fund that provided several hundred dollars a month, and petty thievery. DiPaolo had several brushes with the law, in part, authorities say, because of his involvement with gang activity in Baltimore, and he drifted in and out of drug-rehabilitation programs.

It seems that every local climber has a story about DiPaolo: openly snorting cocaine at the base of a Carderock climb, staging the theft of his climbing rack to collect insurance money, and frequently stealing equipment and clothing from other climbers. His former climbing partner Matt Kull stopped climbing with DiPaolo in the late 1990s because of his drug use on the rock, his stealing, and his sloppy safety practices, which led to several incidents in which other climbers suffered severe injuries when DiPaolo dropped them on belay.

Like his father and sister, Alexandra, DiPaolo had earned a black belt in karate, and a violent side emerged when he was strung out on drugs or felt threatened in some way. Police in Montreal detained him in 2006 after he assaulted his sisterтАЩs fianc├й over some perceived slight.

тАЬDave had a madness, a rage that became more pronounced as he got older,тАЭ says Kull, a 38-year-old English professor at a community college in the Washington area. тАЬAnd he didnтАЩt like criticism, especially the kind of criticism that could come from Geoff if he were upset with you.тАЭ

The mentor-apprentice relationship has been a tradition in climbing for decades, but at Carderock and elsewhere it has started to die out with the advent of climbing gyms and bouldering, where the craft of knots, anchors, ropes, and gear is largely unnecessary. This has created some friction with traditional climbers, who maintain that gym climbers endanger everyone when they go outside because of shoddy safety practices.

Farrar was very much a traditionalist, and thatтАЩs probably why he went out of his way to mentor young climbers like DiPaolo and Kull. Vince DiPaolo endorsed the relationship and permitted his teenage son to spend time with Farrar at his farm near Philippi, West Virginia, where they were close to Seneca Rocks, Franklin Gorge, and other crags.

Farrar had something of a dark side, too, and he could be irascible, critical, stubborn, and, on at least two occasions, physically aggressive to the point of provoking a fight. One afternoon at Carderock, an irate father nearly came to blows with Farrar after Farrar yelled at the manтАЩs children for throwing rocks into the Potomac. On another occasion, two climbing instructors threatened Farrar when he refused to move his bouldering pad from beneath a climb theyтАЩd rigged for a class. Only the intervention of another climber stopped a fight.

Farrar, who was divorced from his first wife and distant from his second, had only one job that anybody could recall: repairing microfilm cameras. He stopped working altogether a few years after marrying his second wife, a librarian with an inheritance. Farrar had a passion for guns, did not trust banks, and regularly buried cans of money in his backyard for safekeeping.

Nobody in the Carderock climbing community is remotely suggesting that Farrar deserved what happened to him, only that a lethal chemistry between the two men existed, and that it boiled over at Carderock on December 28. тАЬLast time I checked, being an odd, cranky old man is not a capital offense,тАЭ says one local climber, who has known both men for decades and asked not to be named.

The situation began to deteriorate the previous day, December 27, when DiPaoloтАФapparently back on narcotics and out of moneyтАФtried to chat up a party of climbers he had never met. A couple of men in the group became irate with DiPaolo when he wouldnтАЩt leave them alone, and Farrar had to step in to prevent a fight. Because of that incident, the two men became furious with each other: DiPaolo for what he perceived as a lack of support, and Farrar for his apprenticeтАЩs return to inappropriate behavior.

Emotions were still raw the next afternoon when Farrar arrived at Carderock. DiPaolo, who had been living in his silver Hyundai van for months, confronted him in the parking lot, just a few feet away from a witness. After a thorough tongue-lashing from Farrar about the previous dayтАЩs altercation, DiPaolo became menacing. DiPaolo told Farrar that he was тАЬjust an old man nobody liked,тАЭ stepped aggressively toward him, dropped his hands, and said, тАЬPunch me!тАЭ

DiPaolo was apparently trying to provoke Farrar so that he could claim self-defense for the beating he wanted to give Farrar. But Farrar didnтАЩt take the bait, and DiPaolo went back to his van to fume, or at least thatтАЩs what a witness thought. It is believed by some, however, that DiPaolo then placed a clawhammer in his orange camouflage backpack, apparently with the intention of attacking Farrar.

A female climber drove up and joined the men in time to hear Farrar say, тАЬIтАЩve stood up for Dave for years, but I guess thatтАЩs over now.тАЭ They were joined by a third, male climber, and then Farrar walked to the base of the crag to boulder, while the other three walked away from DiPaolo and went to the top of the crag to rig some routes. A climber who spoke with Farrar immediately after the argument in the parking lot said he тАЬdid not seem angry or upset.тАж He was laughing and joking.тАЭ

Two of the climbers went to a section of the crag known as Hades Heights to place a top rope on a climb called Butterfly. Farrar apparently intended to free-solo CrippleтАЩs Traverse, which is very close to Butterfly and clearly visible from the vantage point where the other two climbers were setting up the rope. DiPaolo was nowhere to be seen. When one of the climbers leaned over Butterfly to check the anchor before walking down, he saw nothing: neither Farrar, DiPaolo, nor the hammer on the ground that DiPaolo claimed he found there.

Three minutes laterтАФan amount of time determined by investigators during a subsequent reenactmentтАФDiPaolo, wearing a black hooded sweatshirt with the hood over his head and carrying his orange camouflage backpack, sprinted silently by the three climbers as they walked down to their ropes on a rocky, vertical path. One of the climbers said DiPaolo was тАЬon a dead run тАж faster than anyone IтАЩve ever seen.тАЭ Another said his clothes werenтАЩt dusty or dirty in the least, which they should have been if the two men had fought in the dirt.

When the climbers rounded the corner, they found Farrar near the base of CrippleтАЩs Traverse, gasping for air and bleeding from head wounds. Climbers use magnesium carbonate chalk for grip, but Farrar had none of it on his hands, indicating that he hadnтАЩt been on the rock at all.

While the climbers initially assumed Farrar had fallen, it seemed odd to them that he ended up in a position unlikely to have resulted from the height and angle of a fall from CrippleтАЩs Traverse, with head injuries far in excess of what one would expect. Farrar had four deep wounds: on the back and top of his head, on his right temple, and on his jaw. His jaw was broken, and his left eye was bulging out of its socket. One climber said FarrarтАЩs face was so swollen and bruised that he wouldnтАЩt have been sure it was him without seeing his trademark purple Sportiva Mariacher climbing shoes.

The climbers called the Cabin John Park Volunteer Fire Department and the U.S. Park Police to initiate a rescue, and within an hour Farrar was airlifted by helicopter to a local hospital, where he later died.

DiPaolo had completely disappeared and could not be reached by phone. He was arrested on January 8, having been traced to New York State through a cell-phone call and an ATM withdrawal. According to charging documents, he told police that Farrar had choked him as the two argued. Losing consciousness, DiPaolo said, he тАЬfound a clawhammerтАЭ on the ground and struck Farrar until he let go.

тАЬIтАЩm sorry this happened,тАЭ DiPaolo said to investigators. тАЬI didnтАЩt want it to happen. I didnтАЩt know it was going to happen.тАЭ

Authorities concede that DiPaolo is the only one who knows exactly what took place that afternoon at Carderock. But based on forensics, accounts from witnesses, physical evidence, and several interrogations of DiPaolo, they are confident in their reconstruction of the events that day.

DiPaolo is believed to have attacked Farrar with the hammer in those three minutes between the time the climbers finished rigging Butterfly and DiPaolo sprinted by them. With the hammer in his right hand, DiPaolo came up behind Farrar, striking him on the back and top of the head with enough force to fracture his skull. When Farrar, probably already critically wounded, spun around, DiPaolo hit him on the right temple. DiPaolo dealt one final blow to his mentorтАЩs jaw, probably as he lay defenseless on the ground.

Authorities say that wounds on FarrarтАЩs hands are a key piece of forensic evidence that undermines DiPaoloтАЩs story about defending himself while being choked. If that were the case, they say, DiPaolo would have been тАЬswinging the claw hammer at his own neck.тАЭ DiPaolo тАЬdid not answerтАЭ when police confronted him with that evidence during interrogation.

There has been much soul-searching among Carderock climbers and more than a tiny bit of hand-wringing by national climbing groups concerned that this incident might somehow be interpreted as another sign that the heyday of traditional rock climbing, and the largesse of the industries that support it, may be drawing to a close.

Alison Osius, executive editor of Rock and Ice magazine and a former president of the American Alpine Club, came to an agreement with local climber Hunt Prothro on an obituary for Farrar. Within hours, a current senior official with the contacted Prothro to make him aware that the тАЬleadership/board/past presidents of the AAC hopeтАЭ he would write the obituary in a way that the killing тАЬis not seen as a тАШclimbing eventтАЩ showing the devolution of the sport.тАЭ

Prothro, 64, an artist, a teacher, and one of the leading climbers of his generation, responded to the AAC official that he was тАЬsure my words in a Rock and Ice obituary will not be the last ones.тАЭ But he felt тАЬthere is some devolution going onтАЭ in the rituals and traditions of rock climbing.

тАЬIt is the end of an era,тАЭ Prothro told the AAC official. тАЬNobody else has the knowledge of Carderock, the ability, and the willingness to teach/berate/encourage a new generation, many of whom donтАЩt go to Carderock anyway.тАЭ

тАЬThis is a signifcant, multidimensional tragedy,тАЭ Prothro concluded.

Sid Balman, Jr., is a former international correspondent for UPI. He lives in Washington, D.C.