Notwithstanding the mass bullying, fake-news bots, and bizarrely mesmerizing GIFs, Twitter sometimes turns out to be really useful. Case in point: Yale University researcher Adam Chekroud’s (which I only found out about because a Twitter friend pointed it out to me) explaining and giving context about the key points of his massive recent study of the links between exercise and mental health in a staggering sample of 1.2 million people. It’s direct-to-the-people science communication at its best, clearly explained, concise, and engaging. You should read it.

But you should also keep reading here. I’m going to go through some of Chekroud’s key points on what is unquestionably an encouraging paper, but then I’m going to gently push back against one of his apparent conclusions.

The study, which was earlier this month, drew on phone interview data from a massive U.S. survey called the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System between 2011 and 2015. Among the questions were some on mental health, including one about the number of days in the past month in which “your mental health was not good.” And there were also questions about how much and what type of exercise the respondents did.

The headline result was pretty straightforward: people who exercised had 43.2 percent fewer days of poor mental health per month than those who didn’t. That was true even when a bunch of potential confounding factors were taken into account, like “age, race, gender, marital status, income, education level, body-mass index category, self-reported physical health, and previous diagnosis of depression.”

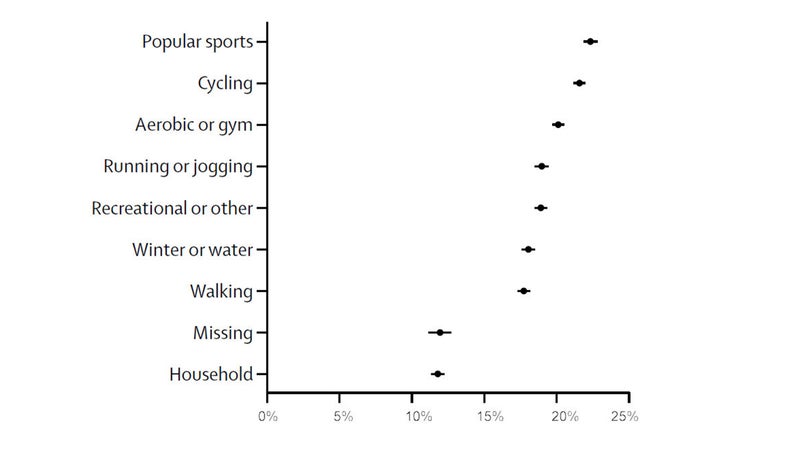

The benefits were present for all types of exercise, but the most powerful effects seemed to come from team sports, perhaps because of the social element. Here’s how various forms of exercise stacked up (the horizontal axis shows how big the effect of exercise on mental health was compared to no exercise; the team sports are labeled “popular sports,” for some reason):

While it’s fun to parse the rankings, the bottom line is that the differences between various types of exercise were minor. Everything was good, even walking (and even household chores like mowing the lawn, though in that case the effects were noticeably smaller). For what it’s worth, Chekroud’s primary affiliation these days is as co-founder of a startup called Spring Health, which is apparently “” with the goal of developing “.” When I look at the data above, my gut reaction is all exercise is good exercise, and you shouldn’t sweat the details, but perhaps there’s more to it than that.

A more important caveat is the old “correlation versus causation” thing. Does exercise improve mental health, or are people with better mental health more likely to get out of the house to exercise? This particular study, based on survey questions at a single point in time, can’t answer that. Other trials where people have been randomly assigned to exercise or not exercise offer some pretty solid evidence that exercise really does affect mental health. But there’s a decent chance that the effects seen in this study are “bidirectional,” reflecting both the mental-health-boosting powers of exercise and the fact that people with certain types of poor mental health are less likely to exercise. That means the true benefits of exercise are probably a little smaller than what’s seen here.

The final point, and the one I want to focus on, is the question of how much exercise is best. As the paper’s abstract puts it, “More exercise was not always better.” The best results seemed to accrue to those who exercise 3 to 5 times a week, for between 30 and 60 minutes at a time. On the surface, this seems reasonable—a nice, moderate exercise regimen that boosts both mental and physical health. But is it reasonable to conclude that doing more than that must be bad for you? That’s what some of the media coverage of the study has suggested. The Telegraph’s headline was “.” The article includes quotes from Chekroud speculating on why exercising 6 or 7 days a week might be bad: “They could be getting run down (physically exhausted) or burned out (mentally), both of which might make them feel stressed or depleted.”

This is certainly possible, of course. But as someone who exercises 6 or 7 times a week, sometimes for more than the magical 60 minutes, I think it’s worth taking a closer look at the basis for these conclusions.

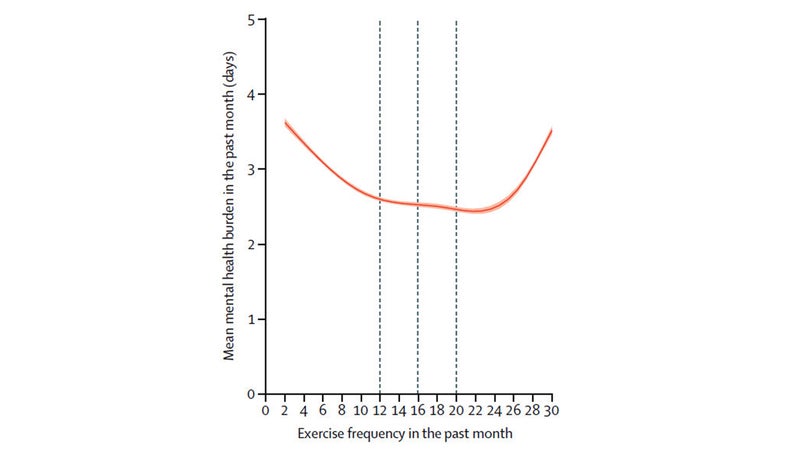

First, let’s take a quick look at some of the actual data. Here’s a graph of the number of monthly days of poor mental health as a function of the number of monthly exercise days:

The dashed lines indicate 3, 4, or 5 days of exercise per week. Interestingly, the curve continues to get lower (i.e. better) beyond the 5-days-a-week line. Now, it’s certainly true that if you break the curve into three chunks (less than 3, 3 to 5, or more than 5 days per week), the middle chunk is best. That’s what the paper states. But if you take a more fine-grained approach, it appears that exercising 6 days a week (i.e. 24 days a month) is at least as good as any other option—which makes it a bit surprising to me that they they’ve pegged 5 days as a magical upper limit.

As it happens, they also analyze the data in total minutes of exercise per week (which is simply the number of weekly workouts times the average duration), since that’s how public health guidelines are expressed. The result should be the same, so an optimal range of 3 to 5 workouts of 30 to 60 minutes each should translate to 90 to 300 minutes per week. Instead, the minutes-per-week analysis yields a higher sweet spot of 120 to 360 minutes—another clue, I suspect, that 3 to 5 workouts a week is a lowball estimate.

Okay, so maybe 6 times a week is great. But it’s hard to deny that the curve is far worse by the time you get to 7 workouts a week. What’s going on here? Again, there are two possibilities. One is that exercising every day is very bad for your mental health. The other is that people with certain types of mental health problems are far more likely to exercise to extremes. The paper notes this possibility in one brief line at the end of the discussion: as they put it, “subgroups at the high end of exercise dose might be enriched for psychopathological risk… (e.g. individuals with obsessive characteristics or personality traits).”

As someone who has been around endurance athletes for most of my adult life, I’d say this seems more like a certainty than a possibility. Scott Douglas’s recent book, , nicely illustrates that a huge number of people use daily exercise as a way of coping with mental health challenges. They may have more “bad days” than average, but they’re better off that they would be without exercise. I suspect the daily exercise group also includes a higher proportion of people struggling with body image problems, which again will lead to a correlation between mental health burden and daily exercise without implying that exercise is causing the problems.

Finally, there’s a methodological point that makes me a bit skeptical about their dosage conclusions. The survey asked respondents “What type of physical activity or exercise did you spend the most time doing during the past month?” Whatever activity the respondents chose, they were then asked how frequently and how much they participated each week. That data is the basis of this study. But what if some people are in the highly unusual and shocking situation of doing… wait for it… more than one type of physical activity?

Personally, I’m a pretty hardcore runner, and that accounts for most of my exercise. But in the past month, I’ve also gone climbing, played in a weekly pickup basketball game, done a bunch of biking and hiking, gone canoeing, played a little frisbee… In this survey, I’d probably show up as a 5-times-a-week runner, but I do something active pretty much every day. I know I’m not alone. So when the authors of this study pinpoint the exercise sweet spot as 3 to 5 times a week for 30 to 60 minutes, that’s the amount people did only for their primary form of physical activity. For those who are most active, I’d be shocked if a high percentage weren’t also getting some additional exercise in other forms, meaning that the true sweet spot for total physical activity is a little higher.

Now, let me acknowledge that this whole piece is basically a giant exercise in self-justification. I exercise pretty much every day, so I’m naturally inclined to look for holes in any data that suggests my approach is bad. To be honest, if someone was struggling with their mental health and asked for my advice about starting an exercise program, I’d probably suggest 3 to 5 times a week as a good goal, and maybe even, as Chekroud puts it, a “sweet spot for mental health.” More isn’t necessarily better. But the point I want to emphasize is that, despite what this study seems to suggest, it’s not necessarily worse, either.

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .