Five years ago, when Eliud Kipchoge became the first person to dip under 2:02 in an official marathon, I wrote a column crammed with superlatives about his “stunning” and “ridiculous” and “crazily incomprehensible” run. I marveled at the 78 seconds he’d sliced off the world record. And I pondered whether Kipchoge was a unique generational talent, a man ahead of his time, or whether his performance presaged a broader shift in marathon running standards.

Watching Kelvin Kiptum crack the 2:01 barrier in Chicago on Sunday morning was a somewhat different experience. Mercifully, unlike the Berlin marathon, I didn’t have to wake up in the middle of the night to watch it happen. But despite a full night of sleep, some of the wide-eyed wonder was missing. After all, we’d just seen Tigst Assefa demolish the women’s world record by more than two minutes in Berlin a few weeks earlier, and even that shiny new record was already under threat in Chicago from Sifan Hassan, who ended up notching the second-fastest time in history. Epoch-making, once-in-a-lifetime performances ain’t what they used to be.

Of course, new marathon records come with a boatload of baggage these days. Was it, yet again, the shoes? Is the spate of new records a function, more broadly, of the hyper-optimized, science-backed time-trial approach to marathoning that has taken over the sport since in 2017? Is the current rate of improvement actually different from what we’ve seen in previous eras? With these questions in mind, here are a few thoughts on where we stand after Kiptum and Hassan’s runs.

Tolstoy Was Right

In War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy railed against the Great Man theory of history, in which the tide of world events is altered by the actions of a few remarkable individuals. Tolstoy’s view was the opposite: even kings, he wrote, are the slaves of history. Kipchoge has been a great marathon king, and it was tempting to view his feats as a singular shift in the trajectory of the sport. But the post-Kipchoge era started on Sunday. It’s not just that he lost—everyone loses eventually—but that his best time was eclipsed before he’d even exited the stage. Whatever granted Kipchoge the power to run 2:01—and we’ll get to the possible explanations in a minute—is apparently available to others too.

That dynamic is even more evident on the women’s side. Paula Radcliffe’s 2:15:25 in 2003 was more than three minutes ahead of anyone else on the planet, and no one even gave it a scare until Brigid Kosgei finally broke it in 2019. But Kosgei isn’t looking like another once-in-a-generation outlier: four other women have broken Radcliffe’s old record in the last year. Radcliffe now sits at sixth on the all-time list—exactly the same spot, as it happens, as Dennis Kimetto, who held the men’s record before Kipchoge. The sport itself is changing, and that means we can look for explanations that go beyond “he or she has one-in-a-billion talent.”

It’s Not the Drafting

Back in June, I wrote an article titled “Why Are Runners Suddenly So Fast?” In that case, I was trying to understand a surge of fast times on the track, and I considered explanations like shoe technology, better pacing, new training ideas, a “training camp” effect from the pandemic, and of course drugs. Most of the same candidates apply to marathon running, along with a few other ideas like new sports drinks and the fact that promising young runners are now heading straight to the marathon rather than spending their prime years on the track. Kelvin Kiptum is 23; Tigst Assefa is 26. Eliud Kipchoge and Paula Radcliffe both ran their first marathons at 28, and previous record-holders like Haile Gebrselassie and Paul Tergat debuted in their thirties.

In previous discussions, I’ve assumed that the two biggest contributors to faster marathon times are shoe technology and drafting. The Breaking2 race convinced people that drafting could save around two to four minutes compared to running alone at elite marathon pace, and researchers continue to study the effects. In August, scientists at the University of Lyon in France on a series of novel drafting formations. The seven-pacer inverted arrow formation used in Kipchoge’s INEOS sub-two-hour run in 2019 would save three minutes and 33 seconds, they calculated. A slightly different formation, still with seven pacers but stretched into a longer pace line, would save four minutes and two seconds.

Those are big numbers. And Assefa’s run bolstered that idea: she ran tightly behind her male pacemakers almost to the very end. But Kiptum punctured it. As far as I could tell, he hardly drafted at all. He and Daniel Mateiko had just one pacer for most of the first half, but frequently Kiptum ran off to the side with no shelter. And he was alone for most of the second half, with no pacers or rivals. That either means that he could have run somewhere around 1:57 with a team of pacemakers, or that the wind-tunnel data doesn’t translate to the real world. The truth may be somewhere in the middle, but seems to be drifting closer to the latter option.

That leaves the shoes, yet again. Assefa’s run introduced the world to Adidas’s brand new, ultralight Adizero Adios Pro Evo 1, priced at $500 and guaranteed to last for just one marathon. Kiptum and Hassan (as well as Kipchoge in his 2:02:42 victory in Berlin) are to have worn a Nike prototype registered with World Athletics as Nike Dev 163, soon to be released as the Alphafly 3. So the supershoe wars grind on. But without any lab data on these new shoes, we have no way of knowing whether they represent yet another leap forward or just the frenzy of a successful marketing push.

What Comes Next?

I intended to close this article with some sort of visual or numerical illustration of just how crazy this current moment is. Every morning, it seems, we wake up to the news of yet another batch of records shattered. It’s clearly anomalous.

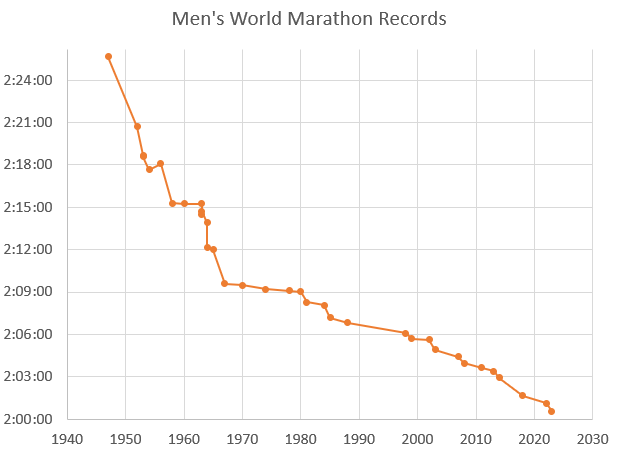

Except that when I looked back at the data, it didn’t seem quite as crazy as I expected. Here’s the men’s record progression since the Second World War. (I’m omitting Derek Clayton’s 2:08:33 in 1969, since .)

It’s no surprise that the slope was steeper back when the marathon was relatively young. But even once we get to the modern era starting in the 1970s, the slope is relatively steady and punctuated by intermittent periods of rapid progress. And more to the point, the frequency of world records is also steady. Here’s the number of marathon world records by decade:

1950s: 6

1960s: 8

1970s: 3

1980s: 5

1990s: 2

2000s: 4

2010s: 4

2020s: 2 and counting (on pace for about 5)

If we’re feeling jaded and sick of world records, what were they saying in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1980s? In the eight years since carbon-plated shoes were first worn in 2016, there have been three men’s records. But there were three records in the six years before 2016.

The women’s data is a little harder to parse because the event has a shorter history. Innumerable records were set in the 1970s as the time dropped by more than half an hour, and there have been two unusually durable records: Ingrid Kristiansen’s 2:21:06 in 1985 stood for 13 years, and Radcliffe’s 2:15:25 in 2003 stood for 16 years. Overall, there have been just five world records this century, including two since 2003. It’s not exactly a deluge.

Let me emphasize that I’m not doubting the influence of the shoes. I believe they’re having a significant impact, and I don’t consider it a positive for the sport that I found myself squinting at the Chicago Marathon broadcast trying to figure out what Kiptum had on his feet. But I do think we should keep the scale of these changes in perspective. Looking back at previous big drops in record times in the 1950s, 1960s, 1980s, and 2000s, we can always come up with some extrinsic, Tolstoyan explanation for why runners were getting faster at that particular moment in history: more money, better training, better nutrition, better shoes, better drugs. Right now it’s the shoes, perhaps alongside some other factors known or unknown, including drugs.

When someone finally breaks the two-hour barrier in an official race—and in this brave, new post-Kipchoge world, I’m now confident that it’s a when rather than an if—we’ll understand that the playing field compared to past greats is not level. It never is. So it might not feel “crazily incomprehensible,” but it’s still going to be fun to watch.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .