If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside.Learn about ¹ś²ś³Ō¹ĻŗŚĮĻ Online's affiliate link policy

What You Need to Know About the New Data Linking Marathons to Colon Cancer

(Photo: Michael Blann/Getty)

At a conference earlier this summer, a research team from Inova Schar Cancer Institute in Virginia presented on colon cancer in runners. Out of 100 marathoners and ultramarathoners between the ages of 35 and 50 who underwent colonoscopies, 42 had polyps, or which 15 were considered advanced pre-cancerous growths. These are bigger numbers than youād expect, and the New York Timesās on the research has sparked a wave of concern.

Iām not here to dismiss those concerns. Admittedly, as a runner and running journalist, I hope the current version of the story turns out to be wrong. And itās easy to poke holes in studies whose results you donāt like: this one doesnāt have a control group, for example, and hasnāt yet been through peer review. But what I really want is to understand whether there are genuine risks that runners need to consider, which is a question that will take further research to answer. For now, here are a few thoughts about the broader context of these findings.

Ā The Links Between Fitness and Colon Cancer

There have been plenty of previous studies on how exercise and aerobic fitness affect the risk of colon cancer. The overall conclusion is that being fitter reduces your risk.

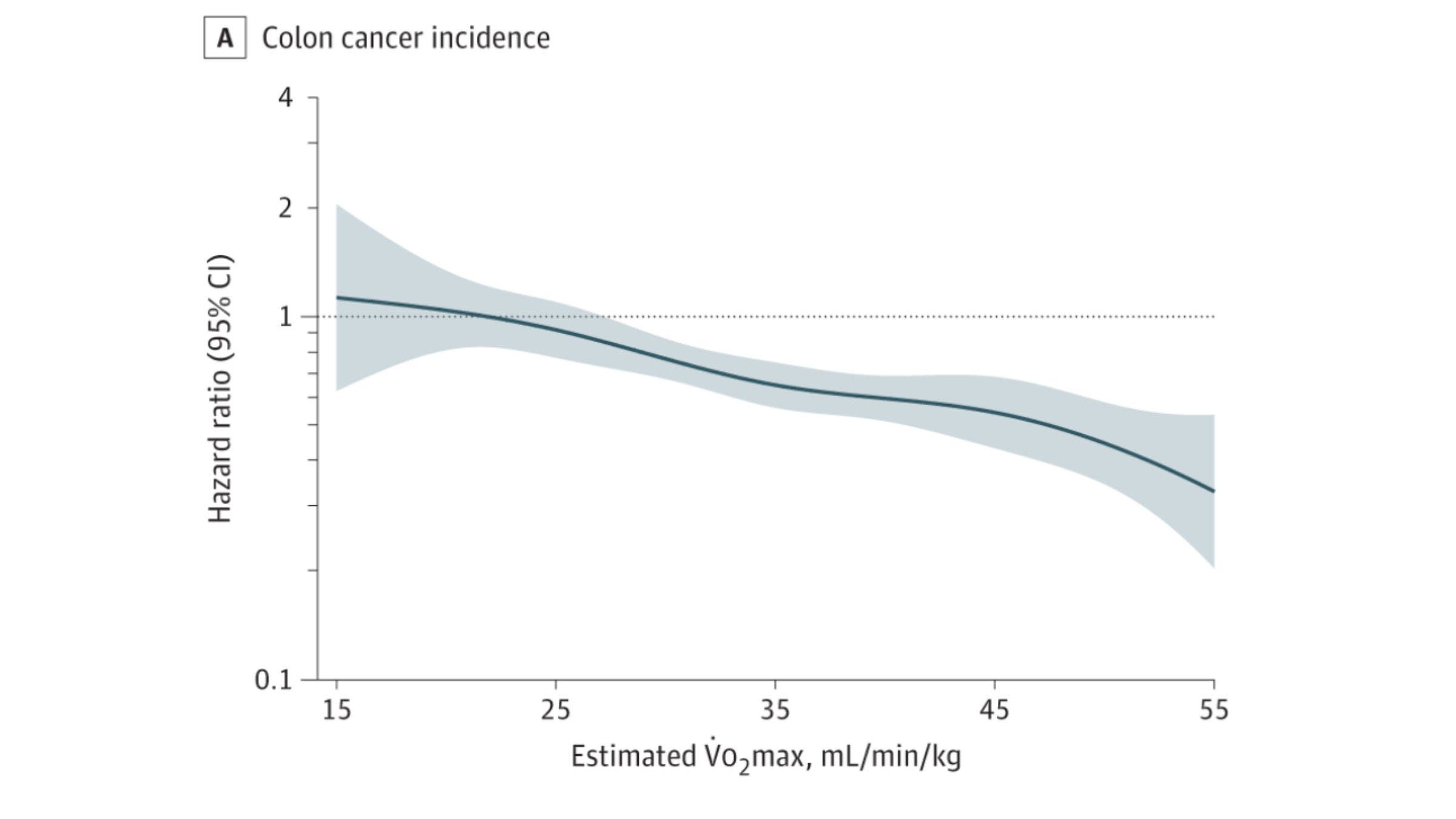

For example, of 177,000 men found that those with the highest fitness (as assessed with an exercise test to estimate VO2 max) were least likely to develop colon cancer over the subsequent decade. Hereās a graph showing their risk as a function of fitness:

You can see that the graph gets steadily lower with increasing fitness: thereās no hint that it turns up for the fittest people. The highest value of VO2 max on this graph is 55 ml/min/kg, which to a marathon time of a little under three hours. These are seriously fit people, in other words.

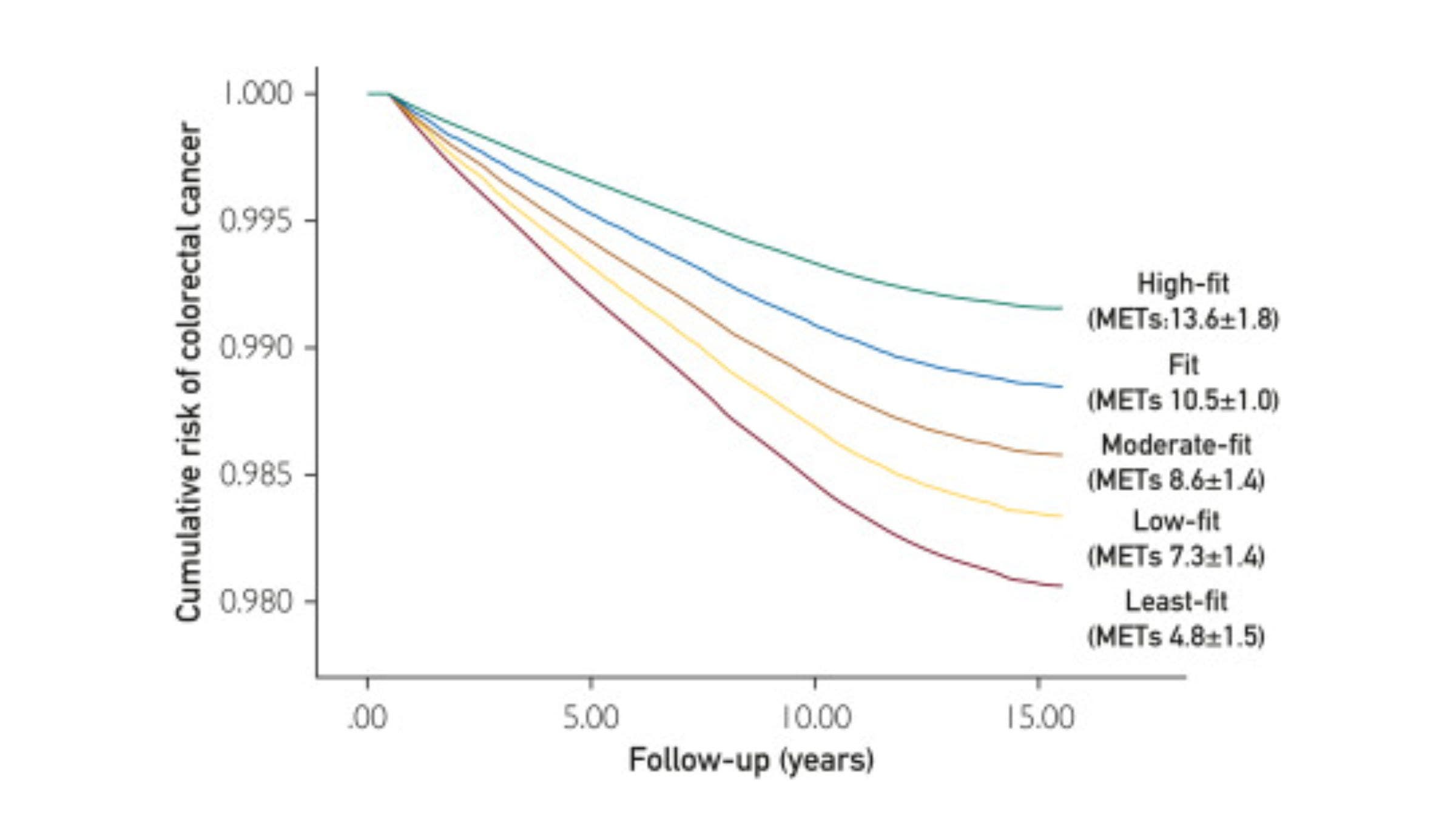

Another study of 643,000 U.S. military veterans, in Mayo Clinic Proceedings, found a similar pattern. Those with the highest fitness were less than half as likely as the least fit subjects to develop colon cancer over time. Hereās that data:

In this graph, each line shows the fraction of people who have not been diagnosed with colorectal cancer, so the higher lines have fewer cases. The āhigh-fitā group here has aerobic fitness of 13.6 METs, on average, which corresponds to a VO2 max of about 48 ml/min/kgāonce again a fairly impressive level of fitness.

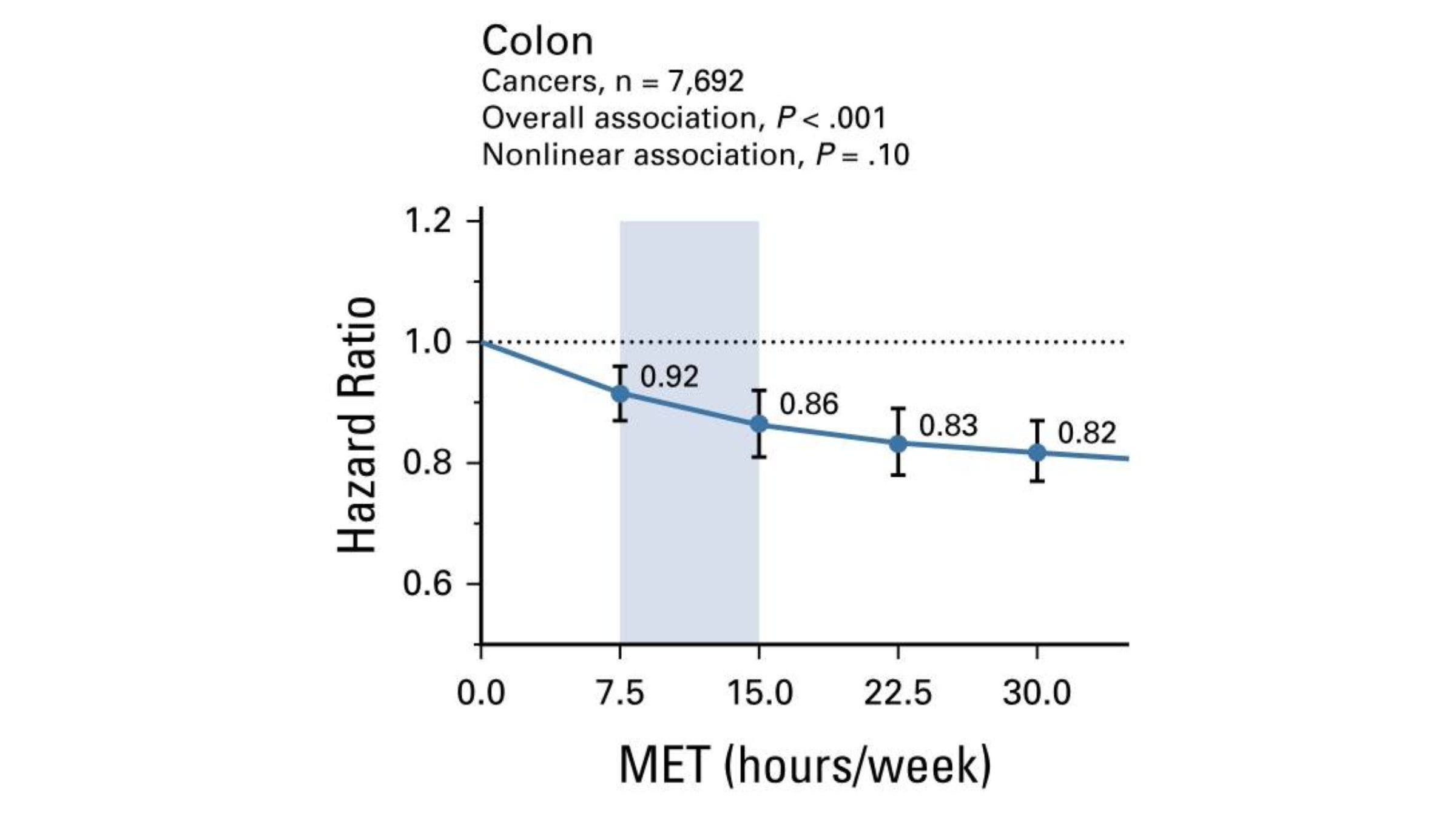

Having a high VO2 max is partly genetic, so itās also worth looking at the data on exercise habits and colon cancer risk. Once again, the relationship is pretty clear. Thereās representative data in that merges data from nine previous studies with a total of 755,000 subjects. Hereās the link between amount of exercise per week and risk of colon cancer:

Exercise is measured in MET-hours, which is basically multiples of your basal metabolic rate. The standard recommendation for exercise is 7.5 to 15 MET-hours per week, which corresponds to 150 to 300 minutes of moderate exercise. The highest group in this study was getting 30 MET-hours per week, or roughly 600 minutes (i.e. ten hours) of moderate exercise per week. Again, this is a pretty active group, with no sign of elevated colon cancer risk.

Defining āExtremeā Exercise

How do we reconcile these two datasets? Thereās tons of data suggesting that relatively high levels of both exercise and aerobic fitness are really good for reducing the risk of colon cancer. But perhaps the new study is testing a different group of people who are doing āextremeā levels of exercise that arenāt captured in these big studies of regular people. The distinction here echoes the debate a decade ago about the potential for heart damage from excessive endurance training. Some of the initial studies claimed that running as little as 20 miles per week could cause problems, but those studies turned out to have serious statistical flaws. Instead, the āextremeā groups sometimes involved people who had done dozens or even hundreds of ultra-endurance events.

The inclusion criteria for the new colon cancer study were that you had to have completed at least two ultramarathons of 50K or longer, or else at least five official marathons. In the running world, this wouldnāt qualify you as some sort of crazy fanatic, but itās certainly more than casual running. Is it enough to mess up your colon? The theory seems to be that prolonged exercise can cause blood to be redirected from the colon, starving the cells there of oxygen and causing inflammation and damage.

At this point, itās simply not possible to say with any confidence whether the new results signal a genuine danger, whether theyāre a statistical fluke, or whether thereās another explanationāthat the people who volunteered for the colon cancer study tended to be people who had already noticed something strange in their bowel health, for example. The findings should generate a wave of new studies that will help us figure out whatās going on.

But itās worth considering what we would do if the results do hold up to scrutiny. There are two points that I think are important to consider. One is that the choice of whether and how much to run is a holistic one: you make it based not just on what it does to your colon, but what it does to your heart and lungs and mind and so on. The overall health risks of running pale in comparison to the risks of not exercising. The second point is that, in the meantime, you should take those potential risks seriously. The American Cancer Society regular screening for colon cancer beginning at age 45.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my new book .