In March 2023, on a trail run in the mountains near Tucson, Arizona, I caught my toe on a rock. I was descending a steep and technical section of trail a little more quickly than I’d normally go. I had a plane to catch. I’m not sure how long I was airborne—maybe a second or so—but it felt like a long time. The aftermath was bad—lost front teeth, deep facial wounds that eventually required plastic surgery—but could have been much, much worse.

Running injuries are distressingly common, afflicting somewhere between 20 and 80 percent of runners, according to one oft-cited pseudo-stat. But it’s mostly sore knees and inflamed tendons and the like: nuisances, but not existential threats. Trail running is different, though. The nature of trails, and the sometimes remote environments they traverse, mean that things can go seriously wrong. At the �����ԹϺ��� Festival last month, I conducted an on-stage interview with Hillary Allen, whose book Out and Back tells the story of her 150-foot fall off a ridge during a mountain race in Norway. Her injuries were a lot worse than mine, but she too has made a successful comeback. Not everyone does.

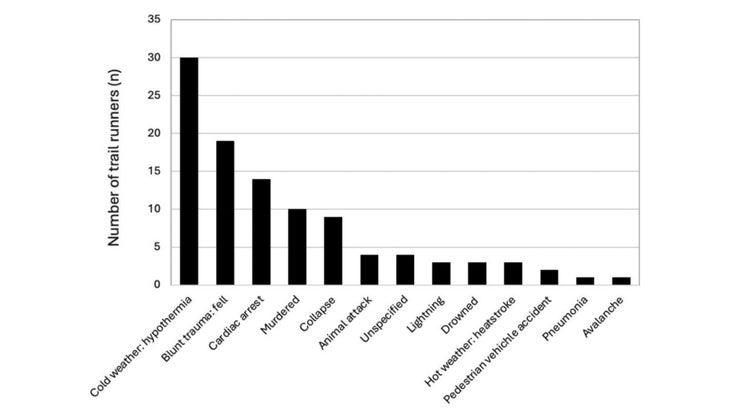

A new takes a comprehensive look at the worst-case scenarios in trail running, with the goal of figuring out what the biggest risks are and how runners and race organizers can mitigate them. Researchers at the University of Pretoria in South Africa, along with colleagues in Portugal and France, combed through online news records for fatal or catastrophic events that occurred while trail running. They identified 127 cases, almost all within the last 15 years, of which 104 were fatal.

The key data from the study is shown in the figure below, which divides fatal incidents into the most common categories:

Cold and Hypothermia

By far the most common cause of death among trail runners is cold weather and hypothermia. This isn’t surprising, especially given that trail runners often run in the mountains, where weather can shift rapidly.

It’s tempting to pack as lightly as possible when you’re running, skimping on warm-weather gear, especially if the weather looks nice. After all, running itself will keep you warm. But what happens if, say, you twist an ankle? Or get lost? Or the weather takes a dramatic turn for the worse? Then you’re sweaty, tired, and inadequately dressed. Under such conditions, it’s possible to become hypothermic even in relatively moderate above-freezing conditions, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as “.” Back in the 1990s, four U.S. Army Rangers died from hypothermia during training exercises in Florida, of all places.

The solution here is obvious but easy to ignore or rationalize away: bring enough warm clothing. Many trail races have rules that specify minimum clothing requirements; it makes sense to take similar precautions on training runs. In the new dataset, 64 percent of the deaths took place during organized trail-running races, with the rest taking place during recreational or training runs. Both scenarios are potentially risky. (In contrast, when runners go missing, it’s almost always during recreational or training runs rather than races.)

Falls

The second-most-common cause of trail-running deaths is blunt trauma after falls. This is once again a trail-specific hazard, and some trails are more rugged and/or more exposed than others. I’m not really sure what to say about this, because “be careful” seems like empty advice. People run trails in part to get away from smoothly manicured roads and sidewalks; the gnarliness of the terrain is intrinsic to what they’re seeking. In doing so, they’re accepting some risk. What’s the “right” level of risk? I don’t know, but in the wake of my Tucson fall, I’ve become a lot more cautious in situations where the consequences of an error are likely catastrophic.

Cardiac Arrest

Third on the chart is cardiac arrest, which is a general risk of exercise (or in fact of living) rather than a specific trail risk. In most cases, such deaths during exercise reflect either underlying heart disease or a genetic heart abnormality. The researchers suggest cardiac screening as a way of uncovering these problems in advance. Whether such screening is worthwhile, much less cost-effective, has been a topic of among cardiologists. Suffice to say that if you have any doubts about your heart health, you should consult your doctor before venturing into the mountains.

Less Common Causes

The rest of the causes of death are relatively uncommon. Murder and vehicle accidents are sad but could occur anywhere. Animal attacks, lightning strikes, and drownings are probably a bit more common on backcountry trails or in the mountains than in city streets, but the numbers suggest these are very unusual. If you’re in grizzly country, pack bear spray and run in a group; if you’re in a thunderstorm, don’t cross exposed ridges; think twice before wading through rivers with strong current. This is all good advice under any circumstances.

The danger in writing about trail-running deaths is that it makes trail-running sound dangerous, in the same way that TV news reports on abducted kids in the 1980s convinced a generation of parents that suburban streets were infested with kidnappers. Given the numbers—the researchers cite data suggesting that 1.7 million people entered trail races between 2013 and 2019, with participation growing by about 12 percent annually—trail running is eminently safe. Still, the data suggests a couple of easy takeaways: pack a jacket, and watch your toes.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my new book .