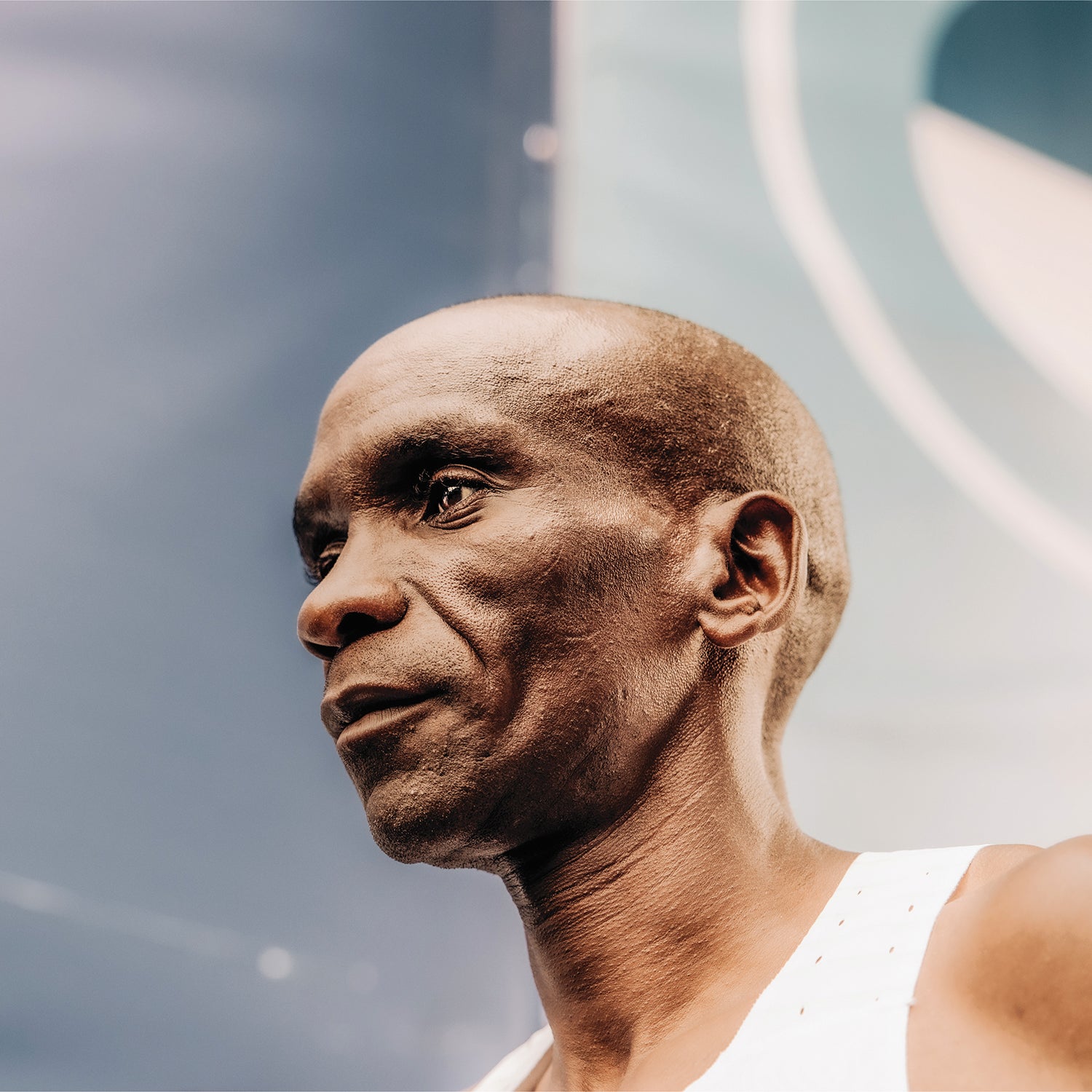

The numbers speak for themselves: 15 victories in 17 starts. Two world records. Two Olympic gold medals. The first human to run 26.2 miles in under two hours. Give me a break. In the decade since Eliud Kipchoge made his debut at the 2013 Hamburg Marathon, the now 38-year-old Kenyan has demolished the grading curve for marathon mastery. In most other sports, the question of who deserves to be called the GOAT is reliable fodder for bar-side bickering. In the marathon, there is no debate.

If anything, Kipchoge’s dominance has created the opposite problem for the running commentariat: What more can be said about someone who seems to win every race, in an event where that kind of consistency isn’t supposed to be possible? Fortunately, Kipchoge’s outsize aura means that every detail of his existence has the potential to become supercharged with significance. In September, after he won the Berlin Marathon in 2:01:09, slicing 30 seconds off his own world record, and both published articles on his water-bottle guy.

“My number one achievement is running under two hours,” he told me recently, referring to the day in Vienna in 2019 when he broke the mythical marathon barrier. After all, other athletes have won Olympic medals and set world records. But when he reeled off 26.2 consecutive miles at a 4:34 pace, he did something unprecedented. What transpired in Vienna wasn’t a race but the manifestation of what a supreme distance-running artist could create in optimal conditions, with 41 of the world’s best offering their pacemaking services, and the latest Nike supershoes on his feet.

Stupendous as the accomplishment was, it didn’t quell a lingering critique of Kipchoge’s marathon oeuvre—that he still needs to show what he can do in an unpaced race with hills. Although he has repeatedly triumphed against some of the world’s deepest, most competitive fields in Berlin and London, all his wins have come on fast, flat courses, usually with a team of pacemakers setting the tempo early, essentially ensuring that lesser talents wouldn’t stand a chance. And while his Olympic victories in Rio in 2016 and Sapporo in 2021 happened in unpaced, championship-style races, neither course featured much in the way of topographical variation. So if you really want to nitpick, you could say that Kipchoge still needs to prove himself on a route with serious climbs.

Now he’ll have his chance. On December 1, that Kipchoge would be running the 2023 Boston Marathon on April 17. The maestro was finally coming to Heartbreak Hill. The news wasn’t exactly surprising, since Kipchoge had long maintained that he wanted to run all six World Marathon Majors before retiring. But Mary Kate Shea, the association’s director of professional athletes, had spent years trying to woo Kipchoge to the starting line in Hopkinton, only for him to repeatedly race the London Marathon (which also takes place in April) instead. Shea was speaking for herself as much as for anyone else when she told me that “to see the world’s greatest marathoner come to Boston and run this race is something I think fans of the sport have been waiting for for a long time.”

Before Kipchoge was the greatest marathoner on the planet, he was one of the best 5,000-meter runners on the track and a regular at world-class cross-country meets. Success came early. Raised by a single mother on a farm in Kenya’s Great Rift Valley, he was 16 when he met his future coach and mentor, the former Olympic steeplechaser Patrick Sang. With the guidance of his countryman, Kipchoge won the junior race at the 2003 IAAF World Cross Country Championships, only to top himself a few months later by at the 2003 World Championships as an 18-year-old. He would go on to medal in the same event at the 2004 and 2008 Olympics. Though he would fail to make the Kenyan Olympic team in the 5,000 in 2012, the setback ultimately accelerated his transition to road racing—a move that worked out well for him.

Kipchoge’s outsize aura means that every detail of his existence has the potential to become supercharged with significance.

The trajectory of Kipchoge’s career affirms conventional distance-running wisdom: that an aspiring pro marathoner should first cut his teeth on the track and cross-country circuits, learning how to run fast and how to race on varied terrain. However, as marquee marathons have become more prestigious—a trend that Kipchoge’s celebrity has surely contributed to—the prospect of spending years grinding it out on the oval has lost some of its luster. Kipchoge’s manager Jos Hermens, whose company has also represented other giants of the sport, including Kenenisa Bekele and Haile Gebrselassie, told me that since the track was “less attractive money-wise,” more of the top up-and-coming African runners are going straight to the roads. (Shea would not disclose the financial terms of Kipchoge’s commitment to run Boston, but it’s reasonable to assume that his appearance fee is well in excess of the race’s $150,000 first-place prize.) Kipchoge is skeptical of this trend and remains a vehement proponent of the old way. “Cross-country and indoor and outdoor track is the key that actually gives you an upper hand on the road,” he says. “Above all, we need to grow. And you can’t grow when you just jump into the marathon.”

Given the air of invulnerability that has defined Kipchoge’s decade-long marathon career, it’s refreshing to watch some of his early races and catch evidence of his own immaturity. There’s from the 2005 World Cross Country Championships where, in the men’s 12K race, he gets outkicked at the finish and is so gassed that he pulls up a few feet short—a bad move, it turns out, as another runner catches him at the line to knock him into fifth place. To see an athlete renowned for his intelligence and poise make an obvious mental error late in a race is a reminder that even the boss man was once a noob.

It’s also a reminder that cross-country running is hard. The hills. The mud. The gnarly weather. Above all, the inherent challenge of cross-country is learning to calibrate your effort to the whims of the competition, as opposed to locking in a pace early and cruising through the first half on autopilot.

The format, in other words, encourages an element of unpredictability—much like the Boston Marathon. Thanks to its lack of pacemakers, dramatic elevation profile, and temperatures that can range from sweltering to hypothermic, Boston has a history of wild story lines and race-day vicissitude. In 2011, a 20-mile-per-hour tailwind helped Kenyan Geoffrey Mutai win the race in 2:03:02, a time that back then was nearly a minute faster than the world record, although Boston’s mono-directional course isn’t world-record eligible. Meanwhile, in 2018, as nor’easter conditions caused mass DNFing in the elite ranks, Des Linden persevered for the first marathon victory of her storied career. (The fact that her winning time of 2:39:54 was the slowest in 40 years was, if anything, a testament to her resolve.) In 2014, Meb Keflezighi was two weeks shy of his 39th birthday when he became the first American in 31 years to win the men’s race, surging ahead of the lead pack early on and somehow maintaining his position all the way to the finish on Boylston Street. It was the kind of bold, tactical gambit that wouldn’t have been possible in a race with pacers, and it bolstered the impression that anything can happen in Boston. As the BAA’s Shea puts it: “We believe anybody on that starting line that we invite to Boston can win this race.”

In an era when innovations in shoe technology have spurred the frenzied pursuit of fast times and record-smashing performances, Boston provides a welcome counterpoint in which race dynamics matter more than the clock. The fastest marathoner in history is the ideal candidate to remind us that sometimes there’s more artistry in tactical brilliance than in raw speed.

For his part, Kipchoge is confident that if he’s fit enough, he’ll be able to handle any sort of race: slow and tactical, or a ripper from the gun. Although he doesn’t plan on adjusting his training to prepare for Boston’s notorious second-half climbs, he hopes to arrive in town early to scout some of the course’s more intimidating sections, like the Newton Hills. “It will give me more peace,” he says.

In recent years, during the lead-up to a marathon, Kipchoge has occasionally spoken about That notion is consistent with his disarmingly earnest belief that his feats of superhuman endurance can provide a glimmer of inspiration for the rest of us as we heel-strike our way through life. Since Kipchoge tends to regard his sub-two-hour effort as the epitome of this principle, I ask him if a “slow” race can be beautiful as well.

“Absolutely,” he says. “Beautiful doesn’t mean that you run very fast. Beautiful doesn’t mean that you run a world record. Beautiful means that you enjoy yourself and that you make your fans happy.”