You’d think that after completing 13 Ironman Triathlons, running across the country in 14 days as part of a nine-member relay team, and clocking a sub-three-hour marathon, Casey Boren would have his training and race-day nutrition and hydration strategy dialed. But throughout his endurance-sports career, he’s been unable to escape painful . “I’ve endured cramping in every Ironman I’ve done,” says the 44-year-old, “to the point that I know if I don’t finish the swim leg in under an hour, my hamstrings will cramp up. On the bike, my quads and hamstrings usually seize up around mile 40.”

He often battles the condition during the run, as well. At a half-Ironman in Knoxville two years ago, his hamstring cramps were so painful that, after he crossed the finish line, he stopped for a second and couldn’t move again. “They told me to leave the area, and I couldn’t,” he says.

Over the decades, Boren has tried everything from sodium tablets to sports drinks. In his experience, “nothing works except slowing down and massaging the tight area and waiting for the cramping to go away, and then hope it doesn’t come back.” But by then, he points out, months of intense training are effectively tossed in the trash. “Once I start cramping, the race stops being about my best performance and is reduced to simply finishing.”

That an experienced and highly trained athlete such as Boren can’t prevent debilitating speaks to their insidiousness and pervasiveness. And he’s not alone. Talk to just about any serious endurance athlete and you’ll hear the same story: When overworked muscles seize up painfully and stop doing what the brain tells them to do, there’s no real fix. To make matters worse, cramps often strike at the worst possible moment. (Exhibit A: LeBron James pulling himself out of the first game of the 2014 NBA Finals due to leg cramps.)

The most popular protocol for battling is to rehydrate using electrolyte-infused fluids. But despite sports nutritionists’ and sports scientists’ best efforts, cramping in athletes has persisted without an effective answer until a turning point in the science took root off the coast of Cape Cod. During a kayaking trip five years ago, a Nobel Prize–winning neuroscientist experienced a painful and potentially disastrous case of .

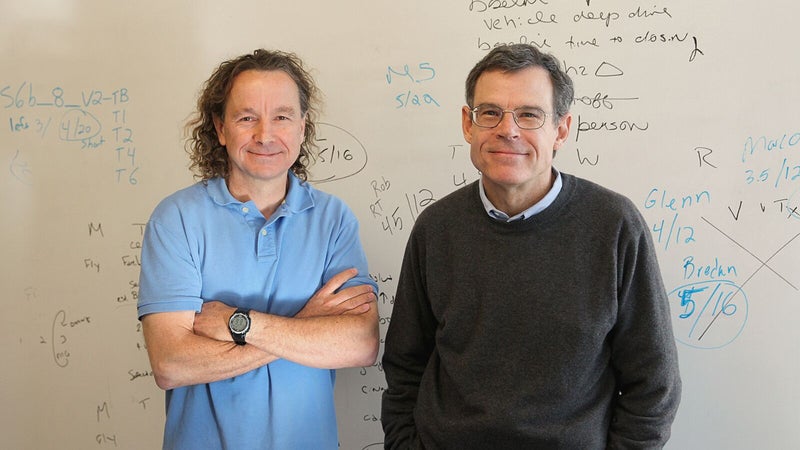

While paddling well offshore, Dr. Rod MacKinnon felt his arms seize up. The chemical-biology professor at The Rockefeller University wasn’t alone in his agony, either. His kayaking partner, Dr. Bruce Bean, a neurobiologist at Harvard, was suffering the same cramping. Both are fit and experienced paddlers who had been paying careful attention to their nutrition and hydration the whole way. They both eventually made it back to shore, but the ordeal drove them to find out what went wrong. For MacKinnon, a serious athlete who had spent the bulk of his career investigating ion channels, his two worlds collided. And when he found out how little we truly understood about cramping, he became obsessed.

MacKinnon’s research started with a look at traditional sports drinks and other electrolyte solutions. His take: They were predicated on replacing what people believed the body lost through sweat—if the body is losing salt or potassium, then restore those levels. But he also came across stories of marathon runners stirring mustard into water and cyclists downing pickle juice to end . He was curious and asked himself, “What’s the story here?”

The more he learned, the more he began to suspect that it wasn’t the muscle that needed help (electrolytes, fluid, carbs), but a short circuit in the ion channels—the system that carries messages among the brain, the nervous system, and the muscle. What the body needed was some sort of stimulation to tell the motor neurons in the spinal cord to, essentially, stop freaking out.

With that realization, MacKinnon spent the next four years in his lab zeroing in on what would eventually become the first clinically proven formula to treat and prevent . By early 2015, he’d arrived at a spicy proprietary blend of ingredients. Here’s how it works: Right before or during a workout, an athlete downs a shot of MacKinnon’s performance cocktail. Ion receptors in the mouth, esophagus, and stomach spring to life, sending signals to the spinal cord, which then shoots out messages throughout the body’s nervous system to keep everything operating normally. Almost everyone has felt this mouth-to-spine-to-body connection when eating ice cream too fast, causing “brain freeze.” Ingesting ice-cold beverages or frosty foods results in a rapid cooling of a cluster of nerves adjacent to the roof of the mouth. For similar reasons, the right formula of spices can trigger a response to cramping.

If MacKinnon and Bean have their way, their research will formally launch a new direction in sports science—one they’re calling neuromuscular performance. Put simply, it’s understanding how the nervous system responds to stress and then manipulating it in such a way that it stays in optimal working order. It’s not mind over matter. It’s not nutrition and energy management. It’s about the nerves, which deliver information throughout the body. The premise is simple: If the pathways are out of whack, cramping happens. Trick them into staying in line, and it doesn’t.

This summer, MacKinnon and his team, who have been working with a select group of unnamed professional and world-class athletes, are wrapping up their research with more trials. (The owners of the New England Patriots and Boston Celtics were early investors in Flex Pharma, the company MacKinnon and Bean set up to research and market their super juice.) If all goes according to plan, Flex Pharma will bring their product to market in 2016.

For Boren, the day can’t come fast enough: “I train and race with a power meter on my bike, and I know that when I’m cramping, it’s not from muscle fatigue—my power is right where it’s supposed to be. And I know it can’t be from dehydration and electrolyte issues, because I follow a strict protocol during a race to stay hydrated. If there’s a theory out there to get rid of , you bet I’m going to try it.”