How to Survive the Arctic Winter in a Broken-Down Camper Van

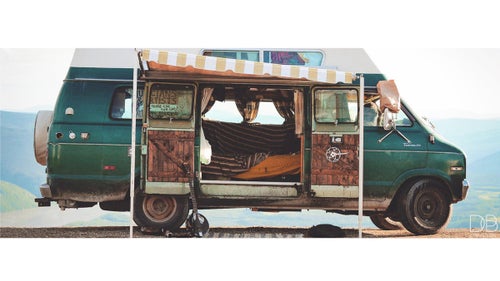

When his 1977 Dodge camper van died in Dawson City, Yukon, a few hours shy of the Arctic Circle, , 28, knew he needed to insulate the vehicle, fast.

The touring banjo player and freelance graphic designer had been planning to try surviving a northern winter in his van, which he’d toured in for years, anyway. It was on his bucket list. “I just wanted to inspire people to do what they love,” says Eastbound, who has “love life” tattooed across his fingers. “I wanted new experiences.”

The busted engine sealed the deal—and the location.

After the engine died, Eastbound spent a few days thinking about how he could insulate the vehicle for the winter. “I wasn’t keen on using traditional pink insulation,” he says. “Because at that point, I might as well just build a little shack.”

Instead, he buried his van in 117 straw bales—a cheap, plentiful, and renewable material.

Stacking the hay bales like building blocks, Eastbound spent a day covering the van.

Eastbound then wrapped his temporary home in a layer of clear polyethylene plastic to waterproof the straw and prevent it from rotting away. The plastic trapped condensation, which caused the roof to sprout greens in the spring.

Next he had to fine-tune his hobbit hole.

He sealed off the stovepipe, which protruded from the back of the van, by surrounding it in metal shelving salvaged from the dump. This was an important step, and one he had to get right to ensure the haystack wouldn’t go up in flames.

The small white CO2 sensor drilled above the dash, a gift from the Dawson Fire Department, proved an unnecessary safety precaution. The van was too drafty to capture carbon monoxide—especially after Eastbound cut a hole in the wall to feed oxygen to the fire.

No light filtered through the straw-covered windows, so Eastbound kept his LEDs on all day, powered with an orange extension cord running through the bush to a neighbor’s house.

Turns out, the straw insulation worked beautifully. Even in temperatures frequently below negative-40 degrees Fahrenheit, Eastbound could sit inside his 80-degree office redesigning websites via satellite Internet on the flat-screen monitor next to the steering wheel or recording mournful banjo ballads.

He also learned from the locals. “I gained experience listening to some really old guys,” says Eastbound. “I wanted to be community based, so I’d give them a hand, and they’d tell me stories.” A weathered trapper recommended that Eastbound shorten the legs on his homemade woodstove to circulate heat better.

It helped, as did the fire-warmed river rocks Eastbound tossed under the covers at night. As winter progressed, Eastbound learned how to stoke the stove with green spruce, topped with dry wood, to coax out a six-hour burn.

When he left the van during the day, he’d fish for Arctic grayling to fry on the woodstove and teach his mutt, Frett, to fetch and stack firewood.

“This is what I wanted to do, so I did it,” says Eastbound. “I make money the way I want, look the way I want, and live the way I want.”

It wasn’t until late May, with temperatures finally hovering above freezing most nights, that Eastbound unwrapped his home and gave the straw bales to local farmers and mushers.

He’d survived the winter in a shelter that cost him less than $850 to insulate, power, and heat. “There are many ways to approach the world,” says Eastbound. “I made myself a nice home. But this summer, I’m thinking of building a cabin.”