The Forest Service Is Silencing Women

For decades, women in the Forest Service and U.S. Department of Agriculture have been trying to bring justice to those who have discriminated against them. A new investigation reveals that the inaction is due to a much larger problem: a system set up to make their complaints go away.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

In 2011, Darla Bush, now a 19-year veteran of the federal Forest Service, accepted a position as a firefighting engine captain at Sequoia National Forest’s Western Divide Ranger District, at the southern tip of the Sierra Nevada. The job wasn’t ideal. She commuted three to four hours a day from the Tule River Indian Reservation, where Bush and her husband had returned to raise their young daughter. The drive made childcare and doctor’s appointments extremely hard. When Bush became pregnant again, this time with twins, her then-supervisor said it made her “useless” to him, according to an Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) complaint she later filed.

Bush’s position required daily hiking or running plus an hour of extra physical training, in addition to standard engine maintenance duties. She asked to transfer to a lower-intensity job during her pregnancy, and claims in her EEO complaint the supervisor asked her to retake her “pack test,” the annual wildland firefighters’ fitness exam that involves hiking three miles in 45 minutes with a 45-pound load, an exam she’d passed earlier that year. She declined and wasn’t approved for the job.

When Bush asked for another reassignment in her third trimester, she said in her complaint, she was instead given odd jobs in a dirty room at the station where mice droppings covered the floor and the elevator squirted hydraulic fluid. After she gave birth, the breastfeeding facilities they offered were so poor that she sometimes went off-site to pump at a tribal gas station instead. (�����ԹϺ��� asked the Forest Service about the specifics of Bush’s claims; the agency did not respond to those questions.)

So when a position opened for an engine captain in another part of the district in 2013, she leaped at the chance. Bush’s then-union representative, Jonel Wagoner, claims that most experienced male officers would have been quickly approved for a “lateral” move—a transfer at the same pay grade that doesn’t require a formal application. Bush, however, had to apply. When she got the position, Wagoner noted in an EEO complaint, there were immediate rumors that the all-male engine crew Bush was to lead had organized a petition against her.

Bush had been working at Sequoia for 14 years by then, including nearly a decade in the eastern Kern River Ranger District, where she oversaw an unusually large docket of missions, from wildland fires to vehicle accidents to river rescues. She came from a long line of firefighters and had become the first female engine captain in her tribe.

But when Bush tried to implement changes—instituting uniform physical training regimens, enforcing safety policies, changing the color of the crew T-shirt—she says that her male subordinates rebelled. All the men on her crew spoke Spanish, and when Bush, who did not, reminded them that agency safety protocol mandated that employees speak their supervisor’s language during work hours, she said they ignored her. When she gave them directions, they looked instead to her second-in-command—who, Bush alleged in a statement to the Forest Service, had told her he should have gotten her job.

When they were on a firefighting assignment at another forest and supposed to be on call 24/7, she said in her EEO complaint, they left without notifying her to go out drinking, which Bush believed might make them unfit for duty the following day. When Bush chastised them, they complained that they were “grown men” who shouldn’t be lectured by a woman, as Bush noted in that same complaint. Sometimes, she said, her second-in-command would become so angry—yelling at her up close, his face red and hands shaking—that she asked him whether she should be worried about her safety. (He declined to answer �����ԹϺ���’s questions.)

Have a story or news tip to share with �����ԹϺ���?

Email, text, or mail it to us.In numerous EEO or administrative documents, Bush described her unsuccessful efforts to get management to help. The supervisor of the forest noted in an affidavit that he commissioned a conflict mediator to intervene, but the men refused to participate. But when several members of Bush’s crew filed complaints charging that Bush had created a hostile work environment by being unapproachable and demeaning, she was quickly investigated.

Initially, Bush said, Sequoia National Forest’s upper management seemed skeptical of the men’s claims. In a class action complaint, Bush claimed the district ranger first responded that he thought Bush’s male crew had waged “a conspiracy” against her; another senior manager said, “You know good and well that if this was a male captain this would not be happening”; and the thwarted mediator reported that “Darla is not the issue.” In an affidavit and a separate declaration, Wagoner claimed the district ranger had told her that the men were ganging up on Bush because she was a woman.

But when several other members of the crew joined Bush’s second-in-command in asking to be transferred from her supervision, a wide-ranging investigation began into whether Bush had a pattern of harassing subordinates. While it was underway, she was removed from her engine captain position—a practical necessity, argued the district ranger in a later affidavit, since transferring the men would have left the engine shorthanded in the midst of fire season.

As Bush claims the district ranger told her, “What did you want me to do? It was five against one. It was easier to move you than them.” Less than a week later, her second-in-command was named captain in her stead.

In 2014, Bush became the lead agent on a class action complaint, Bush et al. v. Vilsack, filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) on behalf of all female firefighters in the Forest Service’s Region 5, which primarily covers California and is one of the most active sectors of the agency. (The case is now called Bush et al. v. Perdue, because former Georgia governor Sonny Perdue replaced Tom Vilsack as the secretary of agriculture in 2017. It is still in the administrative EEOC process and has yet to be filed in federal court.) It was the fourth class action regarding gender discrimination brought against the region.

In 1972, the first complaint, Bernardi v. Madigan, resulted in a 1981 settlement that came to be known as the Bernardi Consent Decree, compelling the region to ensure that it of women as were then in the civilian workforce—43 percent. The Forest Service responded by flooding the region with women it had done little to train, and , as many men felt they were passed over for jobs. They denigrated female colleagues as “Bernardi” women or “Consent Decree” (sometimes “cuntsent decree”) hires, presumed to be incompetent.

In 1995, shortly before the court enforcement of the Bernardi Consent Decree was set to expire, Lesa Donnelly, a paralegal and former Forest Service employee who now represents individuals as vice president of the nonprofit advocacy organization USDA Coalition of Minority Employees, filed and settled a new class action complaint, based largely on the post-Bernardi retaliation women had faced. But when enforcement of the Donnelly settlement quietly ended in 2006, conditions reverted to the old status quo. (A third class action complaint was brought in 2011, but the EEOC dismissed it as being overly broad.)

When Bush chastised them, they complained that they were “grown men” who shouldn’t be lectured by a woman, as Darla Bush noted in a 2015 statement.

Even before the #MeToo movement gained steam, stories of pervasive sexual harassment and assault in wilderness jobs were rampant. In early 2016, revelations of a decade-long at Grand Canyon National Park of congressional . That December, the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform followed up with a hearing on the Forest Service and for years of inaction on sexual harassment. This March, a on sexual harassment in the Forest Service revealed that its then-chief, Tony Tooke, who was , was himself under investigation for sexual misconduct. Tooke resigned within days, and his replacement, interim chief Vicki Christiansen, , yet again, the agency’s handling of sexual harassment complaints.

But there’s a deeper story to tell about what women face in the Forest Service, and in the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) under which it falls—not just aggressive come-ons and groping, but also an employment structure that remains intricately rigged against them and a complaint process designed to turn them away. While on-the-job harassment may be one of the most visible indicators of inequality, it rarely occurs in a vacuum.

Bush is just one of eight agents in the class complaint. Several hours south of Sequoia, at Angeles National Forest, north of L.A., 54-year-old aviation firefighter Darlene Hall has spent most of her adult life in the Forest Service. She first joined in 1980 as a member of the Young Adult Conservation Corps. After leaving to start her family, Hall returned in 1987 as a seasonal employee. The following year, Hall claimed, she and her female co-workers were told that no seasonal employees would be rehired. In order to stay on, they’d have to apply for a special program that would convert them to permanent employees. But doing so required demotion to the lowest pay grade in federal government. For Hall, that meant dropping from a seasonal employee GS-5 to a GS-1; in practical terms, cutting her salary of $5 an hour roughly in half. Hall said she later talked to several male seasonal employees and they were not required to do the same.

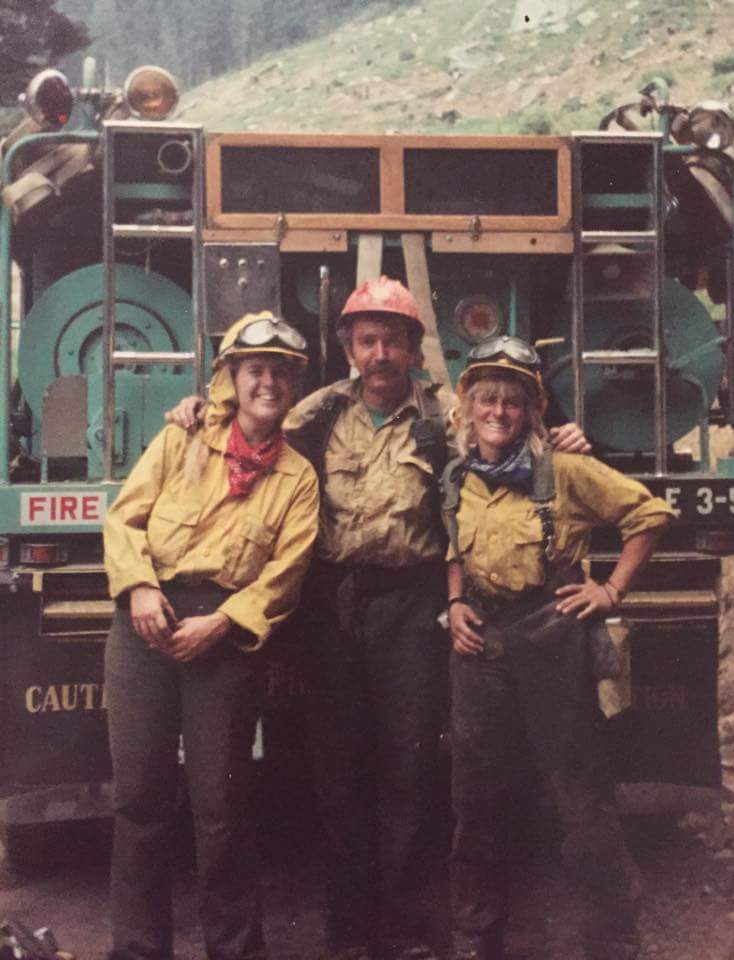

Hall worked her way up, taking jobs in almost every department in the fire organization—aviation, dispatch, engines, prevention, recreation—and developed a training guide for air base managers. A petite woman with blond hair and a pilot’s tanned face, Hall speaks in clipped, efficient sentences, with a trace of a Boston accent. She estimated that for almost every Forest Service woman, on-the-job discrimination starts out with sexual harassment when they’re young. “When they can’t get you that way anymore,” Hall continued, “then it rolls into the reprisal, the harassment, the bullying. But it continues.”

In 2008, Hall reluctantly filed an EEO complaint after she said she realized that her supervisor at Lassen National Forest, in Northern California, was giving her false negative references—ones that didn’t match her performance reviews, thus blocking her applications for promotions or transfers.

In the Forest Service, firefighters amass literal “qualifications” based on tasks and trainings they’ve fulfilled. A firefighter who has filled certain roles receives a qualification—an actual checkmark in their task book—to apply for a higher position. In theory, that means the hiring process should be more objective than in the private sector: An applicant either has a qualification or does not. Instead, said Jonel Wagoner, who also worked at Sequoia as a training officer, male managers have consistently found ways to make the process subjective—by questioning or devaluing women applicants’ qualifications and inflating those of younger, less experienced men.

“For a long time,” Hall said, “I was the most highly qualified aviation female in the region, and I couldn’t get jobs.” According to written testimony Hall gave Congress in 2016, her supervisor was instructed to stop giving her negative references as part of a 2009 EEO settlement. In the same testimony, she said she had put in more than 50 formal applications for promotions from 2002 to 2010 and received none of them.

In one instance in 2012, Hall noted in an EEO document, her supervisor simply refused for four months to approve an upgrade to her qualifications. The supervisor even took the anomalous step of declaring that he would “abstain” from the Forest Qualifications Review Committee’s vote on Hall’s credentials—holding up the process and prompting a fellow committee member to question whether he had “other motives” for refusing to participate, according to Hall’s EEO complaint.

When her supervisor finally retired that year, Hall said she received three major promotions in less than two years, the first just months after he left. (Her former supervisor did not respond to a request for comment.) But Hall’s advocating for herself had marked her as a problem employee, with a reputation that followed her to her new positions. “Basically, when I spoke up,” she said, “I committed career suicide.”

Lesa Donnelly, the former Forest Service employee who brought the second class action against Region 5 and who now represents Hall, Bush, and Wagoner as members of the fourth, ongoing class complaint, said that concern about reprisals for reporting discrimination is the most common complaint she hears from Forest Service women. One of the most obvious cases was Denice Rice, another of Donnelly’s clients who has worked for 17 years at California’s Eldorado National Forest, southwest of Lake Tahoe.

In 2011, Rice filed an EEO complaint against her second-line supervisor after enduring what she claimed was years of sexual harassment including graphic comments, stalking, and assault—she says the supervisor poked her breasts repeatedly with a letter opener and followed her into a bathroom to try to lift her shirt. In the immediate aftermath of her report, Rice , she was isolated from her co-workers and stripped of her supervisory responsibilities. The supervisor was allowed to retire rather than be fired and was later invited back to the forest as a motivational speaker.

In December 2016, Rice testified before the House oversight committee, sparking a vow from one outraged representative to “g” to protect her and other victims from retaliation. Yet, just last year, after Rice successfully advocated for Eldorado to recreate a position that included her old duties, she was given the job only on a temporary basis. A man from outside the forest was hired instead.

To even start the process of getting restitution for sexual harassment or thwarted career advancement—however dim the prospects—U.S. Forest Service employees first file a complaint, itself an often ludicrously opaque and inaccessible process.

There are four different options for filing complaints, not all created equal. If an employee reports a problem through their chain of command or to the agency’s human resources headquarters (the Albuquerque Service Center, known as the ASC), that office will either designate it as an internal assessment, performed by management, or a more formal “personnel misconduct investigation,” typically conducted by outside contract investigators. Alternatively, employees can also file a grievance through their union or alone.

All three processes, Donnelly said, amount to internal investigations, controlled by management, whether at the forest level, the ASC, or the USDA’s Office of the General Counsel, the entity tasked with defending the department against personnel complaints. “It’s the fox guarding the chicken coop, because when you file a grievance, management is making the decision on whether to sustain or substantiate your complaint,” she said. “Employees just don’t have a chance.”

The only other avenue for employees to address misconduct is an EEO complaint, which is handled by the USDA’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights (OASCR) rather than management. But even that process can be baffling. Employees have just 45 days after an incident to file an initial complaint, compared to 180 to 300 days in the private sector, depending on the state. Those are then examined by an EEO counselor, who typically suggests mediation. If the complaint isn’t settled then, employees have 15 days to file a formal EEO complaint with the OASCR, which assesses the legal grounds for the complaint. If the OASCR allows it to proceed, a contract EEO investigator gathers evidence—including affidavits, documentation, and witness statements—and the OASCR determines whether to dismiss the complaint or allow it to move forward.

“For a long time,” Darlene Hall said, “I was the most highly qualified aviation female in the region, and I couldn’t get jobs.”

If it does move forward, the OASCR sends a report of investigation to the employee, along with three options: withdraw it, request an agency-written final decision, or ask for an EEOC hearing under an administrative judge. Most of these steps also include the opportunity to appeal.

Many employees—even experienced staff with supervisory experience—get lost in the process. A woman I’ll call Kate, a 25-year veteran of various wilderness agencies who often worked in management, filed her first-ever EEO complaint in 2017 after taking a Forest Service job in the American South. (�����ԹϺ��� is withholding her name and the specific forest she worked for because Kate fears she’ll be blocked from future federal employment, thereby compromising her pension.) In an office culture wherein the female employees frequently cooked for the entire staff, Kate alleged her boss berated her constantly for failing to conform—for being too assertive and direct and not recognizing “who is the boss here.”

But when she decided to file a complaint, Kate found little help to navigate the process. She didn’t even realize there was a 45-day window for filing for several weeks, leaving only 25 days to make a decision that “would basically guarantee that I’m going to get blacklisted,” Kate said. “That’s terrifying as a 25-year employee who has built my career on working in public lands.”

In 2009, when Secretary Tom Vilsack took the helm of the Department of Agriculture, he promised to usher in a “.” At the time, there was a massive backlog of EEO complaints against the department, left largely unaddressed during the Bush era. The following year, in 2010, Vilsack presided over two settlements, totaling nearly $2 billion, for black and Native American farmers who had in accessing the USDA’s loan and disaster relief programs. (This issue was so systemic, said Lawrence Lucas, president emeritus of the USDA Coalition of Minority Employees, that for years the agriculture department was referred to as “.”) When the Obama administration expressed concern about the repeated complaints coming out of the Forest Service’s Region 5, the USDA took some initial steps to address the issues, including commissioning to investigate employee complaints and instituting an agency-wide “cultural transformation” program.

But the program amounted to little more than rhetoric, Donnelly said. “The problem is we have managers at all levels who condone it. They’re not committed to making a change.” The heart of the problem, argue Donnelly and Lucas, is the dismissive treatment of complaints at the highest levels of the agency, including the OASCR.

In 2015, following accusations from several whistleblowers within the OASCR, the Office of Special Counsel—the federal internal watchdog agency that monitors government personnel practices—wrote a letter to the White House noting that the USDA’s civil rights office “has been seriously mismanaged, thereby compromising the civil rights of USDA employees.”

Hostile Environment

An �����ԹϺ��� investigation of sexual harassment in outdoor workplacesThe whistleblowers alleged that OASCR managers deliberately slow-walked EEO complaints, with some complaints simply vanishing from the system—meaning that by the time employees tried to check their status, more than 45 days had passed, precluding them from filing again. (When the USDA conducted an investigation of the charges, it found no evidence of deliberate delays or deletions, but “attributed complaint file anomalies to server and power failures.”) One whistleblower further charged that they were pressured to weaken EEO complaints and that there were numerous unresolved cases against managers within the civil rights office itself. An OASCR response to the 2017 EEO complaint of whistleblower Nadine Chatman acknowledged 42 EEO complaints filed against three upper-level managers in the division. Some internal complaints had lingered for years.

What’s more, some whistleblowers and their supporters claim that the OASCR was sharing complaint information with and seeking guidance from the USDA’s Office of the General Counsel—two departments that, under management guidelines of the EEOC, should be completely separate. (A 2003 EEOC review confirmed such line-crossing at that time as well.) Yet a new USDA regulation released this January gave the OGC additional power to determine whether the department will settle complaints and the authority to review all settlement agreements over $50,000.

The office seems to actively resist acknowledging agency misconduct, said a current OASCR employee. “You can’t have 500 complaints and no findings of discrimination. It can’t be that we’re not doing anything wrong.”

When Congress heard testimony about the Forest Service’s sexual harassment problem in 2016, the Office of Special Counsel letter regarding OASCR mismanagement was submitted as evidence. Donnelly testified to its relevance: “I question how the Office of Civil Rights can address systemic and institutional issues of discrimination when they are not capable of managing their internal personnel problems and violations of civil rights.”

This February, that charge was illustrated in dramatic fashion when, in the midst of a USDA celebration of Black History Month at the department’s Jefferson Auditorium, a 17-year employee of the department, a woman in her mid-fifties, took to the stage in front of hundreds of her colleagues.

“My name is Rosetta Davis, and I’m here to tell you that all is not well at USDA,” she said, according to someone in attendance. Davis went on to explain, in a brief, emotional speech that was partially recorded, that she’d had with her former supervisor, David King, director of the OASCR’s Office of Compliance, Policy, and Training.

Davis had joined the USDA in 2001, working on EEO complaints from Forest Service employees facing retaliation. Soon after she started, Davis claims in her own lawsuit against the department, her then-supervisor asked her to shred incoming EEO complaints before they were investigated. Davis refused and filed an EEO complaint herself, but it seemed to go nowhere.

In 2008, she came to work under King. For years, she'd tried unsuccessfully to promote beyond her GS-12 level. King, Davis claimed in her lawsuit, said that if she had sex with him, he could help her reach GS-13. (King declined to speak on the record; the details contained in this account appear in Davis’ lawsuit.) It was part of a culture, Davis announced during her public outcry this February, where a female supervisor once told her, “You’ve got to give some of this”—patting her crotch—“to get some of this”—rubbing her thumb and forefingers together.

Davis claims in her suit that she began a relationship with King that continued for some months, until she says he began pressuring her to have anal sex and she ended things. After that Davis says in the lawsuit that she “became the target of aggressive sexual harassment and brutal retaliation.” Davis filed an EEO complaint against him in 2009.

That complaint, she alleges, also resulted in no action from the USDA. When Davis called the intake office to inquire about its status, she claimed in an interview with �����ԹϺ���, she was told they had no record of it; by then, her 45-day window had passed. (The inaction on one of Davis’ complaints was among the cases brought up in one 2015 whistleblower statement.)

But the retaliation came swiftly, she claims. According to her lawsuit, the USDA “transferred her involuntarily to numerous sub-agencies and re-classified her position at least three times in order to thwart her efforts to obtain a promotion or otherwise advance her career; and targeted her with other acts of retaliatory ridicule, insult, and intimidation.”

“It was awful, awful, awful for many years,” she told me. According to the lawsuit, she was transferred from the USDA’s Cultural Transformation Initiatiive to another program within the D.C. office without explanation; and in another instance, she was moved to the Farm Service Agency. She claims in her lawsuit that while there she overheard a supervisor—alleged to be King’s friend—instruct her new boss to “make her as uncomfortable as you can.” (The supervisor did not respond to emailed questions.) Davis said she was not given an office, cubicle, telephone, or computer to perform her work duties for several months. The culture at work became so toxic, she told �����ԹϺ���, that she suffered anxiety attacks and high blood pressure that frequently sent her to the department’s nurse.

It was part of a culture where a female supervisor once told Rosetta Davis, “You’ve got to give some of this”—patting her crotch—“to get some of this”—rubbing her thumb and forefingers together.

“The minute somebody makes an EEO complaint, they’re a target,” said attorney Yaida Ford, who is representing Davis in her lawsuit against the USDA. “It’s a measure management will use to get rid of the person, because it’s hard to fire [federal employees]. So, if they can’t build a case for termination, they will try to make it so miserable for you that you resign.”

The Woman Ending Harassment at the Grand Canyon

For decades, the staff of Grand Canyon National Park has lived with a culture of bullying and harassment. Can the park's first female superintendent heal the old wounds?

For decades, the staff of Grand Canyon National Park has lived with a culture of bullying and harassment. Can the park's first female superintendent heal the old wounds?This February, after years of workplace hostility, Davis said she felt compelled to plea for help during the February USDA celebration. “Why won’t anyone do something about this? Can someone please help me?” she asked the stricken audience, according to someone who was there.

The next day, the department placed her on immediate “precautionary” administrative leave, informing her in a letter obtained by �����ԹϺ��� that she and her family were prohibited from speaking to anyone at USDA.

“The real irony is that this was in the Office of Civil Rights—the vanguard for enforcing these policies and anti-harassment and anti-discrimination policies,” Ford said. “Here are the people who have been charged with enforcing the agency’s policies and doing these thorough investigations and making sure they’re properly addressing the allegations of discrimination and sexual harassment, and yet they are the main perpetrators.”

This March, USDA Secretary Perdue boasted that the OASCR has “dramatically improved its track record of handling formal EEO complaints in a timely fashion” and had completely cleared its backlog of complaints. But to advocates who work on employees’ cases, that’s largely a matter of complaints being dismissed or complainants being pressured into abusive settlements.

“It’s easier to process complaints faster when you’re just rubber-stamping non-findings,” Ford said.

In the past year, however, an OASCR employee told �����ԹϺ���, the EEOC has been rejecting dismissed cases and non-findings of discrimination, sending multiple cases back to the civil rights office to be processed again. In February, the EEOC sent a memorandum to all federal EEO officials, reminding them to maintain “vigilant separation of the investigative and defensive functions” of federal agencies—the firewall that should exist between offices of civil rights and agencies’ general counsel.

In the meantime, Donnelly says, the Forest Service has responded to its multiple PR crises with familiar promises of task forces and training while continuing to retaliate against individual women who’ve filed complaints.

In 2013, after more than a decade of blocked promotions, Darlene Hall became the forest fire aviation officer at Angeles National Forest—a position she’s glad to have, but one she unsuccessfully applied for five times before. Two months in, however, a letter sent to management accused her of representing a systemic safety issue to the forest. The Forest Service removed some of Hall’s duties for more than six months. When additional complaints are filed against Hall, she said, they are investigated immediately, while some of her own have lingered, unaddressed, for years.

Stuck at the same Sequoia district, Darla Bush—once an agency lifer who “bled green”—is languishing in the ambiguous, largely clerical position created for her after her engine captain duties were removed. Bush has no real job description and, according to an EEO complaint she filed this March, “sits at her desk doing nothing for the majority of the pay period waiting for managers to assign her project work,” forced to watch passively as her firefighting qualifications expire, not allowed to undertake trainings or assignments to keep them current.“If I could walk away, I would,” Bush said. “I don’t consider myself a firefighter anymore.”

Kate, the Forest Service officer from the southern United States, ultimately resigned from her position in despair. After a colleague referred her to Lawrence Lucas at the USDA Coalition of Minority Employees, she managed to file her EEO complaint. It was settled earlier this year, though she can’t discuss the terms. Before Kate accepted it, she and Lucas said, she was offered a different settlement, which offered her more money if she agreed to never reapply to the Forest Service again.

“There’s no other agency in any other department in federal government that is as bad as the Forest Service,” said Lucas, who added that the coalition’s repeated attempts to schedule a meeting with Secretary Perdue have been met with silence.

I experienced something similar when �����ԹϺ��� sent the USDA an extensive list of questions. A spokesperson responded with a short comment that read, in part: “It is always the goal of USDA to address claims of discrimination fairly and equitably…To respect the federal sector process, USDA will not address individual allegations of discrimination when an individual has claims pending before the EEOC or a District Court.”

Lucas believes the department’s entire OASCR should be put in receivership, “Just like you do a failed city or local government: Take it out of the hands of people who have controlled it all these years, and fix it and give it back to them so they can do it right.”

After Eldorado firefighter Denice Rice’s supervisory duties were removed in 2010 by the supervisor who she said harassed and assaulted her, she said her position was also deleted from the forest’s organizational chart. Following her congressional testimony in 2016, Rice redoubled her efforts to convince the forest to bring it back. In 2017, they relented, opening the position under the upgraded title of prevention battalion chief. In July 2017, Rice was briefly assigned to it on a detail basis, meaning for 60 days she had her old job back while the agency looked for a permanent hire.

But when selection officials at California’s biannual “Fire Hire” were reviewing applications last fall, Rice found that she was shut out of consideration. Some of the officials were personal friends with her harasser, and others had been involved in her EEO complaints. Despite nearly two decades working in prevention, Rice’s internal record had been revised to say her qualifications had expired, and that she was now a mere “fire prevention trainee.” She said colleagues who were present at Fire Hire told Rice her name never made it onto the short list of contenders for the job she’d held for years.

In November, Rice filed an EEO complaint over this latest incident. And because a recent Forest Service policy mandates that any manager or official who learns about alleged harassment or discrimination must report it to the agency’s new Harassment Assessment Response Team (HART), Rice also participated in an official HART inquiry. Although the Forest Service has refused for three years to negotiate any settlements with members of the class action, something about Rice’s EEO complaint spurred the USDA’s Office of the General Counsel to call her soon thereafter, offering to settle.The man who had taken her old position was gone within four months, and Rice was offered a portion of her old job back. She accepted, reasoning, “eight years [of being sidelined] is long enough,” and has subsequently received more of the patrol and lookout duties she used to hold. Although Rice says that her pay hasn’t yet increased correspondingly, after “eight years without sleeping, now I sleep like a baby.”

On May 8, an email went out to Rice’s office, announcing her new title as prevention battalion chief of the forest’s Pacific Ranger District. That evening, when she got up from her desk to go home, the men at her station rose as well, standing at attention, saluting.

It seemed like a happy ending. Then, in late July, a day after �����ԹϺ��� sent the Forest Service questions regarding Rice’s allegations, she received an email from Eldorado management, informing her of a new investigation—into her conduct. Rice was being accused of harassment and bullying by the same man who, Rice alleged in her HART statement, had participated in inviting her harasser to give a motivational speech at the forest after he’d retired. “Just when I think it’s over,” Rice said.

Although there was a time when she wished she’d never filed, Rice said she was no longer prepared to back down. “I kept on saying I don’t want to fight anymore,” she said. “I’m fighting this one.”

Kathryn Joyce () is the author of and . This article was reported in partnership with at The Nation Institute.