On June 23, 2018, twelve members of the Wild Boars, a youth soccer team based in the jungled mountains of northern Thailand, and their young assistant coach parked their bikes in the mouth of Tham Luang Cave after practice. The cave network was dry when they entered, but as they traveled more than a mile on foot into its dark, dank limestone recesses, a monsoon descended. It was the first major storm of the wet season, and it caught everyone on the ground by surprise. There was no time for officials to close the cave, and by the time they found the boys’ bikes, Tham Luang was already flooded.

The subsequent 18-day search and rescue operation was an unprecedented collaboration involving Thai government officials, Thai Navy SEALs, members of the U.S. Air Force, local farmers, Thai hydrologists and engineers, and, most famously of all, . The entire country of Thailand tuned into this story from day one. Although it appeared the boys were almost certainly dead, the nation held out hope. Once the boys were found alive, hundreds of reporters and thousands of volunteers from around the world joined the scrum outside the cave, and millions of people across the globe became invested in the boys’ fate. So it was exhilarating when, despite the stacked odds and the many ever-shifting perils, every last one of the Wild Boars was pulled out of the cave alive.

Talk about a Hollywood ending.

The day after the coach and the last of the boys were rescued, filmmaker Jon Chu, whose film Crazy Rich Asians would soon become a global hit, that put his industry on notice: “I refuse to let Hollywood the Thai Cave rescue story! No way. Not on our watch. That won’t happen or we’ll give them hell. There’s a beautiful story abt human beings saving other human beings. So anyone thinking abt the story better approach it right & respectfully.”

Four years later, those Hollywood offerings are finally streaming. , a National Geographic documentary by Free Solo directors Jimmy Chin and Chai Vasarhelyi, hit theaters in September 2021 and is now on Disney+. , a feature film directed by Ron Howard and starring Viggo Mortensen and Colin Farrell, dropped on Amazon Prime on August 5. And now , a limited series executive produced by Chu, is being released by Netflix on September 22. Finally, rumors are circulating that the streaming giant is also working on a documentary about the events.

While it remains to be seen if the public has an appetite for this much Thai cave content four years after the fact, I found it fascinating that so many top writers, filmmakers, and stars were attracted to the material. What was it about this story that captivated them, despite all the competition? And did any of them get it right?

William Nicholson, the two-time Oscar-nominated screenwriter, was following the rescue from a distance like everybody else in the summer of 2018, but when he was first approached to write Thirteen Lives he didn’t see drama in the happy ending. Then he dug into the details of what happened and realized how improbable the rescue was, and saw there was a very compelling movie to be made.

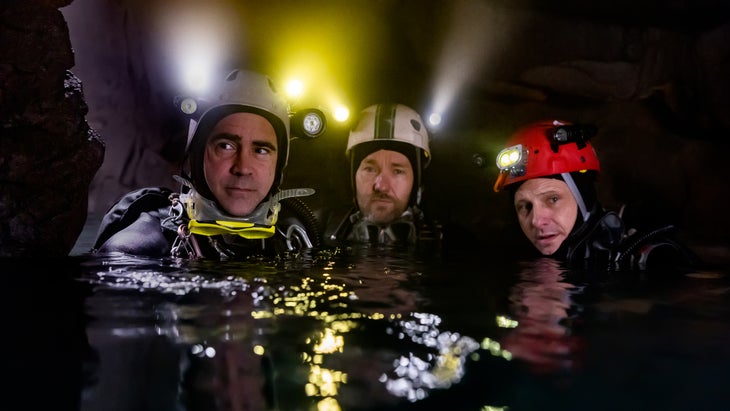

Thirteen Lives centers on two middle-aged English cave divers involved in the effort: retired firefighter Rick Stanton (Mortensen) and technology consultant John Volanthen (Farrell). They take over the underwater search and rescue operation from the Thai Navy SEALs, who lacked the relevant cave diving chops required to find the kids. That’s not a knock on the Thai navy—U.S. Navy SEALs don’t have that capability either.

“Here’s these divers,” Nicholson says. “They’re old, they’re amateurs, nobody pays them, they’re grumpy, and yet they are the only people who can do this particular job. And they go in, and they finally find the kids and make videos of them. And they come out and everybody cheers, and everybody’s happy. But these guys know the truth that all these kids are dead.” Navigating Tham Luang—with its many hazards, currents, and low visibility was difficult for even the accomplished cave divers, and they knew that diving those kids out of that cave would be exceedingly dangerous and perhaps impossible.

Stanton and Volanthen possess the dry humor and brazen lack of fashion sense found in most tech dive shops, and the dialogue is appropriately spare, too. It’s an intense yet understated film. Nothing is over-explained. You get the sense that Howard and Nicholson, and even Farrell and Mortensen—who deliver captivating but restrained performances—were content to stay out of the way.

“It kind of fell into a dramatic structure by itself,” Nicholson says. While the divers were busy trying to find the kids and devise a workable rescue plan, rain was still falling, and the water was rising. The only way to bring down the water levels was to flood and ruin the rice crop of local family farmers. “Then in the three days of the actual rescue, they’re racing the return of the rain. They get out most of the kids, and literally on the night before the end, down comes the rain. You couldn’t create a more ticking clock than that.”

In scope, Thirteen Lives closely mirrors National Geographic’s documentary The Rescue which also mostly focuses on the divers. Because P.J. van Sandwijk, an accomplished documentary producer turned Hollywood player, produced both films after successfully negotiating for the rights to Stanton’s and Volanthen’s stories.

In previous projects, Chin and Vasarhelyi have leaned on their most unique selling point: that Chin can physically get to places that are well beyond the abilities of other cinematographers, and then return with jaw-dropping material. The Rescue is more of a straight-ahead documentary. It blends archival footage, revealing interviews, and well-made underwater reenactments. Chin and Vasarhelyi sifted through hundreds of hours of news coverage to pin their story together.

However, in both Thirteen Lives and The Rescue, the kids and their coach, who was orphaned as a young boy and raised in a Buddhist monastery, are relegated to the background. This is despite the fact that they all maintained an incredible amount of faith and composure through the most harrowing of experiences—in part, by leaning on meditations and chants led by the coach. If that’s what Chu was worried about when he sent his Tweet—yet another movie succumbing to the tired white savior trope—it has a lot more to do with access than interest or awareness on the part of the filmmakers.

In the aftermath of the actual event, one of the trapped boy’s parents set up a trust to represent the Wild Boars and their families in future film rights negotiations. That mattered because most of these kids were 13 and 14 at the time, and in Thailand you remain a minor until you’re 20 years old. SK Global, the company that produced Crazy Rich Asians, secured those rights, tapped Chu to executive produce their series, and then . As a result, Chin, Vasarhelyi, Howard, and Nicholson were boxed out.

“It normally doesn’t work like that in nonfiction because it’s journalism,” says Chin. “But we navigated it as best we could.” In the end, he and Vasarhelyi zoomed in on the cave divers—taking pains to make sure that all the gear and techniques were dialed in to the last detail for their reenactments—and their risky plan to retrieve the Wild Boars. They are gifted adventure filmmakers, after all, and The Rescue is yet another banger.

There’s a maxim in journalism: the later you are, the smarter you have to be. I wouldn’t go so far as to call Netflix’s Thai Cave Rescue smarter than The Rescue or Thirteen Lives, but it does benefit from being able to feature the perspective of the 12 boys (Titan, Tee, Phong, Adul, Biw, Dom, Night, Nick, Mix, Note, Pim, Namhom) and their beloved Coach Ek. “John Chu wanted to be true to the story and start where the story started, which was with the boys,” says Dana Ledoux Miller, an American screenwriter who has worked in television writers rooms for ten years. Miller was called in by Michael Russell Gunn, a writer and producer on Billions, to write and create the series together. “It started with local officials who were doing their best under extraordinary circumstances and it grew from there. We really tried to capture the magic that is northern Thailand.”

I’ve reported from Northern Thailand several times. In fact, I reported on this very rescue, and in my opinion, Gunn and Miller’s series successfully bottled the magic. This was thanks in no small part to their all-Thai crew, including director Baz Poonpriya, and the deep level of research that went into creating the series. Gunn and Miller, neither of whom are Thai or Asian for that matter (Miller is part Samoan), interviewed the boys and their families extensively with the help of translators, and delved into the Thai government’s archives. They shot the series in Thailand, and some scenes were even filmed in the first two chambers of the real Tham Luang cave and the boys’ actual homes. They cast local people in lieu of professional actors to fill the roles of some of the boys and their parents. To decorate the shrine outside the cave for a pivotal scene, one of the mothers turned up with the same offerings they’d prepared when their boys were trapped inside.

“John Chu wanted to be true to the story and start where the story started, which was with the boys,” says Dana Ledoux Miller

In the first episode alone, five different ethnic dialects are used, and throughout the series the local Buddhist-Animist culture is featured prominently. Some episodes have the look and feel of a foreign film. However, aside from standout performances by Papangkorn Lerchaleampote (Coach Ek)—a rising star in Thailand who tragically died during the editing process—and renowned Thai actor Thaneth Warakulnukroh (Governor Narongsak), the acting is spotty.

The action is too. The team behind the Netflix series made a deal with Dr. Richard Harris, the cave diving anesthetist known as Doc Harry who is the only person alive with the combination of skills that could have made the rescue possible, and who put his medical license on the line to do it. But he doesn’t turn up until the second to last episode. Even then, Thirteen Lives—in which Harris is played by Joel Edgerton—serves that slice of the story better. The Rescue includes interviews with the man himself, which is even more compelling. That’s the trouble with focusing on so many scenes where the divers are not. Although time with Coach Ek and the boys is always well-spent in Thai Cave Rescue, there are a few too many logistics meetings where the threat of expository dialogue hovers like so many storm clouds. (A side note for Netflix: scuba and tech divers use air tanks, not oxygen tanks.)

And yet, in the final act of each of these three projects, when the rain is falling harder than ever, the dams and diversions are failing, and the last of the boys is carried out from the cave alive, it’s hard not to be moved. Because no matter which way you examine it from, or where the story is centered, the lessons of this improbable rescue come through.

“To be honest, I was worried that if this story was told from an eye of an outsider, the story will change in its essence,” says Poonpriya, who directed two episodes of the Netflix series including the pilot, and is known as one of Thailand’s best filmmakers. “However, I came to understand that the richness of the story has encouraged all the productions—whether it be the documentary, the series, or other treatments of the rescue—to be done with heart and attention to detail.”

In other words, here was an irresistible adventure tale that could have easily been sensationalized, or mishandled in a way that was offensive to the Thai people, and yet all three treatments produced compelling and thoughtful entertainment that actually complement one another. That couldn’t have happened without the sensitivity and skill of the filmmakers and the power of the rescue itself. “It stands for something,” Nicholson says. “Why did 10,000 people descend on those caves, saying, ‘I will do anything? What do you want me to do? Clean the latrine, cook, sweep, push water around? Whatever you want, I’ll come and do it.’ I truly believe that people’s deepest instinct is to cooperate, to work together to make things better for everybody. And it’s not a message we’re given enough.”