This story update is part of the �����ԹϺ��������������������, a series highlighting the best writing we’ve ever published, along with author interviews and other exclusive bonus materials. Read “The King of the Ferret Leggers,” by Donald Katz here.

“The King of the Ferret Leggers,” which appeared in the February–March 1983 issue of �����ԹϺ���, tells the story of a Yorkshireman named Reg Mellor who, for sport, puts two ferrets down his pants and then stoically endures as the rodents run and claw, bite and dangle, for five-plus hours. Details on the activity, which peaked in the 1970s, are a little sketchy, but it appears that all you needed was a field for spectators to stand around in, some self-appointed judges, and at least one contestant. Oh, and the competitors had to go commando: no underpants.

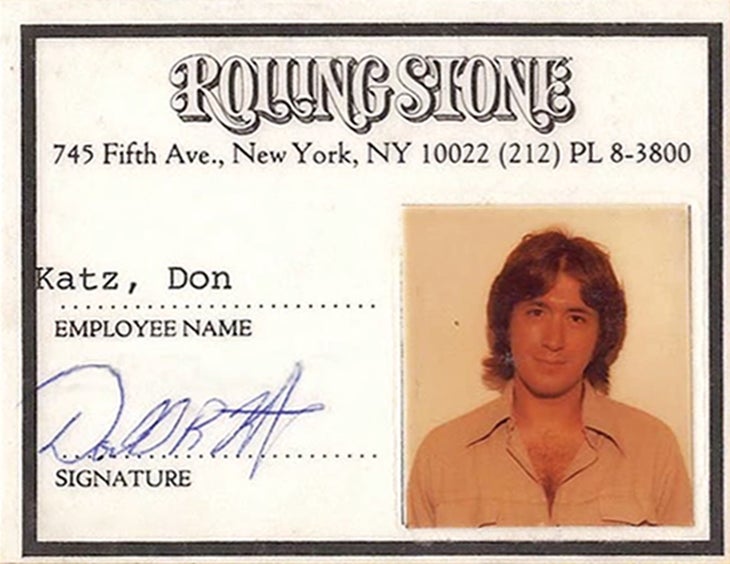

The author of this tale was Don Katz. Forty-two years later, he’s recounting the legend of this piece to me while sitting inside a majestically repurposed church in Newark, New Jersey, global headquarters of the company he founded: , the world’s leading creator and seller of audiobooks and other original content. Katz recently stepped back from his longtime position as CEO, but he remains active and keeps an office in town. He also remains close to Newark Venture Partners, a social-impact early-stage investment fund, and Audible’s Global Center for Urban Innovation; he established both to focus on solutions to urban inequities, after moving Audible to Newark in 2007.

Hold on a minute: the guy who wrote a piece about ferrets gnawing a man’s privates is the same guy who created Audible? Yes, and a common thread runs through �����ٳ�’s writing career and the business he built: a love of story.

In late 1982, Katz submitted the ferret-king piece to John Rasmus, then ���ܳٲ������’s editor in chief. This was back in the magazine’s primordial days, when it was still finding its voice. Rasmus loved it. Then the artwork came in—a graphic image by , the famous Rolling Stone artist, showing Reg on the field of battle, clad in baggy pants that appear to be spraying blood.

Rasmus: “I said, ‘Uh-oh.’ ”

Katz had talked Steadman—his good friend and colleague from their days as Rolling Stone contributors in England, where Katz had moved to study at the London School of Economics before getting started as a writer—into illustrating the piece. Delicately, Rasmus nestled the article and its vivid depiction into the issue, running it with a brief subhead (“A True Story”) under the rubric “Revelries of the Rustics.”

It’s not an exaggeration to say that this piece became talismanic for the magazine. “It gave us all kinds of good reasons to do stories like ‘Ferret Leggers,’ ” says Rasmus, who in 2017 wrote a tribute to it for ���ܳٲ������’s 40th anniversary issue. It also helped establish that an �����ԹϺ��� story could be literary, visceral, and funny at the same time, often involving a protagonist who must do a particular thing because, to paraphrase George Mallory, it is there to be done.

“Ferret Leggers” is so good that it was stolen many times, even before the internet made that easy to do. People typed it up, put their name on it, and got it published. Katz, who for years worked as an award-winning magazine writer and author, spent more time than he wanted to cease-and-desisting these thieves.

�����ٳ�’s decision to write for a living, and in particular his ability to hear and employ the oral traditions of storytelling in his work, was born in the early 1970s, when he studied at New York University under , the author of the classic novel Invisible Man. The idea of what Ellison called the “musicality” of the spoken word surely was lodged in �����ٳ�’s head while he labored to bring Audible to life. It wasn’t easy. The company would eventually become a huge success, but after the dot-com bust of 1999, Audible traded for as little as four cents a share. It took a decade to make a profit.

�����ٳ�’s two career arcs reminded me of something he wrote about ferrets back in ’83. This creature, he observed, has one very good trait: “a tenacious, single-minded belief in finishing whatever it starts.”

OUTSIDE: As a character, Reg Mellor is hilariously over-the-top, and I think some readers today may wonder if he treated his athletes with the respect and care they deserved.

KATZ: Well, Reg would have said that the real athletes were the tiny cohort of humans who subjected themselves to ferrets being put in this uncaring and potentially cruel situation. My story set out to be a literary satire, pitting legendarily tough Brits from a specific county against equally tough animals, which, as few readers would have known, had been raised and deployed for generations to chase other animals out of holes for the benefit of hunters. There’s no doubt that there were plenty of people around England more than 40 years ago—when there was a movement to outlaw ferrets as pets due to various attacks that happened inside homes—who gave me statements and assertions that became my description of exaggerated ferret fury. But ferret legging was a clearly unacceptable treatment of sentient beings. From my view—as someone who’s aware of emerging science about animals and the father of a vegan animal-rights activist—it’s good that this is no longer a thing, which leaves my literary excursion into irony as a cultural artifact of another time and place.

How did you get the idea to write “The King of the Ferret Leggers”?

When I got to England in the mid-seventies, there was this satirical, couched-in-gossip magazine called Private Eye. I saw a squib in there about someone named Reg Mellor, who had retired in disgust from a competition called ferret legging because he was able to do it for so long that everyone in the stands got bored and left.

I pulled the page out of the magazine and thought: That is so weird. Someday, I’d like to find out what that is.

I bounced the idea off Ralph Steadman, who was already famous in the United States for his Rolling Stone work with Hunter S. Thompson. I kind of put us together as a package. For whatever reason, I got the OK from �����ԹϺ��� to do it.

The story was published, and it fairly immediately became a cult thing. People passed it around at cafés, as if we were living in the days of Victorian poetry. Writers sent it to each other, and it started to have, you know, buzz—and all sorts of unintended consequences for me.

Such as?

Right around that time, I had this idea of trying to write a big story about Nike. The head of Nike, Phil Knight, had never given interviews. I sent him “Ferret Leggers.” He loved it. I got the OK to enter Knight’s world, and that experience grew into my 1994 book, Just Do It: The Nike Spirit in the Corporate World.

I’ve read that “Ferret Leggers” was stolen a bunch of times.

The story comes out, and I go back to writing books and other magazine articles. Then I get a phone call from a friend who was talking to another friend in Germany who was raving about this hysterical article in a major German magazine, about a man in Yorkshire, England, who puts ferrets down his pants.

“You’ve been plagiarized,” he said. I lawyered up and was paid triple damages—which wasn’t that much because of how small my �����ԹϺ��� fee was. But at the time I needed the money!

In the late 1990s, when the Unix-based Internet was becoming the World Wide Web, I became aware that the story was available online with other people’s bylines on it. I remember writing to some person at Carnegie Mellon University who was trying to publish it under his name.

I said, “You might not know the concept of intellectual property, but I wrote that. I basically live on that story being republished.” And the kid wrote back, saying, “You old fart, you should be happy that anyone even cares about a story you wrote in 1983.” He attached various manifestos that said information should be free, which was one of the early ideas defining the Internet: to wipe out professional-grade content in favor of the crowd’s content.

Later, when Audible was designing the first download service for content—and inventing the first digital-audio player, which came out almost five years before the iPod—I asked our engineers to create an encryption system that would at least cow the people who wanted to steal others’ work. I said at the time: “If we’re going to sustain the professional creative class through this digital transformation, there have to be some protections. Otherwise, no one’s ever going to get paid.” That was key to Audible’s formation, and a focus on powerfully composed and artfully performed words was fundamental during the 27 years I ran the thing.

For many people the writer-to-tech-CEO trajectory might be confusing at first, but it makes sense that the common link is a love of words.

That’s right. Audible was an idea and a company culture led by a writer. And the truth is, I daydream in prose.

How did you get the elite venture capitalists who backed you to believe in a writer who wanted to create a media category based on technologies that didn’t yet exist?

Well, some of them didn’t believe. But because I’d studied and written about businesses large and small, I knew that getting a business going required capital, and I would need to deploy language and stories that would overcome perceived risk. I discovered, for instance, that 93 million Americans sat in traffic jams driving to and from work—which meant there were hundreds of millions of hours per week that Audible could fill with a premium service offering self-selected entertainment, education, and information. This was a key point in the original business plan. Consumers could “arbitrage” their time, I argued, by programming their own listening time. They could make dead time come alive and get to work smarter than the person in the next cube.

That’s a daunting leap.

The technology-invention risk, on top of the market risk, was real, but I used my journalistic training to be honest about what I didn’t know, and to find expert fellow pioneers and employees to supplement that. The realities of financial and cultural success took much longer to achieve than I expected, but from the beginning I thought—and preached—that digital technology could create an Audible-spawned media category alongside music, books, and other printed material, along with all permutations of film and video. I didn’t go so far as to attribute this to what I learned as an English major mentored by Ralph Ellison, or go on as I did later about why Stephen Crane and Mark Twain wrote like Americans because of their ability to listen to the polyglot sound of Americans talking. But these things were never far from my thoughts.

You also had to invent the technology and the hardware to make it happen. You had to invent the Audible MobilePlayer and a way to download encrypted files. And last but not least, you had to persuade the book publishers to license the rights to books.

Despite the efficiencies of never being out of stock in digital, and the price benefits of no physical packaging, resistance from the publishing establishment was intense. There remained an aristocratic strain within the publishing elite that did not want this change.

This seems like the right time to tell you that, by studying your vast oeuvre—magazine pieces, books, and Audible itself—I’ve identified themes that run through your work. May I try them out on you?

I love that you did that.

My first theory is that you’re drawn to people—you may be one of those people—whom the mainstream considers to be, uh, crazy. People who have outrageous ideas and pursue them. Reg Mellor is such a person.

Definitely true. I also think of them as relentless people who just don’t give up on ideas. In my case, the shift from writing to creating Audible was, even to myself, something of a mystery.

Two more themes: you’re drawn to endurance and domination. Both apply in “Ferret Leggers,” but also in �����ԹϺ��� stories like your profile of the father of fitness, Jack LaLanne, which was memorably called “Jack LaLanne Is Still an Animal.”

Jack was such a fascinating, bloody-minded character. He was 80 when I spent time with him, and I think of him often now, as I navigate the realities of aging alongside continued aggressive physical activity.

And, obviously, in the story of Audible, which hung by a thread several times between 1995 and its sale to Amazon in 2008. By 2023, according to one statistic I saw, Audible dominated the U.S. audiobook business, with nearly two-thirds of the market.

There are many ways to define business success, and Audible has clearly achieved a startling level of it by traditional metrics. But what has always mattered to me are the lives that Audible touches in so many ways across listeners, writers, actors, and employees. But there’s no question that if you want to pursue ideas that others may view as unlikely, you better need to win and fear failure in ways most others do not.

Do you have any regrets?

That I was never good enough to be an NHL player. I’m a lifelong hockey player. I would have traded in any of it to be a professional.