Hey, we’re with you. Given half a chance, we’d much rather hit the road than the armchair. Nothing can replace the intensity of authentic experience. Yet experience needs shape and wisdom and behind every great adventure are the stories that inspired it. We read before we go; and after we arrive, free and clear in far-flung terrain and edgy places, we invariably find echoes of the voices that led us there.

The following list is devoted to books that offer the truest inspiration, the deepest reflection, the strongest provocation. These are books that seize imaginations and rattle sedentary lives

Longtime readers will note that this is our second venture in literary list-making. The first �����ԹϺ��� Canon, which appeared in May 1996, spanned many centuries, from Gilgamesh to Al Gore, and encompassed a host of genres, including fiction, sports, environmental manifestos, natural history, poetry, and how-to books. This time around, we were determined to drill to the core. To compile the distilled contents of a tool kit for adventure literacy. The writing, we decided, must be urgent and contemporary in spirit, so we narrowed our sights to the past 100 years or so. No fiction. No collections and no geopolitical reportage. (Otherwise, how could we pass up Cahill and Kapuscinski?) Nothing classic for the sake of self-importance we wanted two-fisted, readable works defined by an insatiable appetite for the world at its wildest. Books that do what the indomitable boxer Joe Frazier had in mind when he said, “I don't want to knock my opponent out. I want to hit him, step away, and watch him hurt. I want his heart.”

These books stole ours.

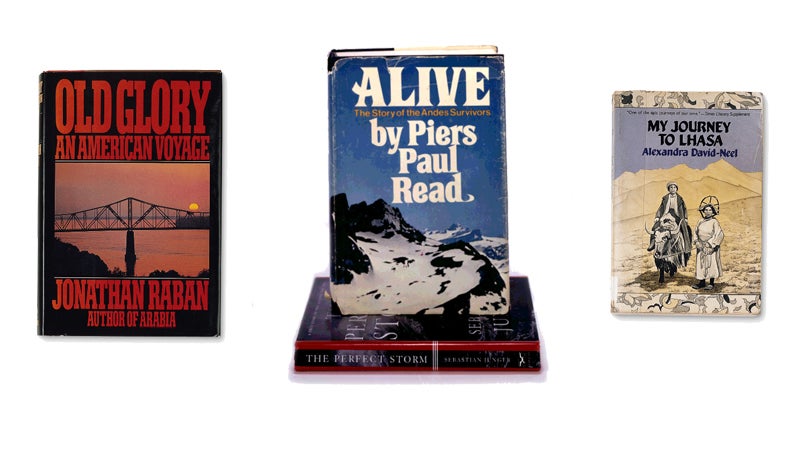

25. ‘Old Glory’ by��Jonathan Raban��(1981)

There are grander adventures than Raban's on this list, but few as eloquent. “I found that I had landed up in a tree slum,”�� in a 16-foot aluminum boat down the Mississippi, “where overcrowding and miscegenation had made it almost impossible to make out the individuals in the tangled mass. … They didn’t seem to be aware of the opportunities for trees in North America.”��Though Raban’s wit is always intact, we do sometimes question his fortitude. (What’s up with his mortal fear of birds?) But we’re suckers for his Brit’s-eye view of America and for his Huck’s-eye view of the Big Muddy: “I drifted downstream, just letting the river unroll around me. … The charts and tree book seemed hopelessly thin and theoretical when set against the here-and-now of the Mississippi itself. The river was simply too big, too promiscuous … it would never tamely submit to posing for its portrait.”

24. ‘A Walk in The Woods’ by��Bill Bryson��(1998)

Hands down, you’ll ever read on long-distance thru-hiking. In his lazy, TV-addled pal Stephen Katz, Bryson couldn’t have picked a less prepared partner for an attempt on the Appalachian Trail nor a better comic foil. “For two days, Katz barely spoke to me. On the second night, at nine o’clock, an unlikely noise came from his tent the punctured-air click of a beverage can being opened and he said in a pugnacious tone, ‘Do you know what that was, Bryson? Cream soda. You know what else? I’m drinking it right now. And I’m not giving you any. And you know what else? It’s delicious.’”

23. TIE: ‘Alive’ by��Piers Paul Read (1974); ‘The Perfect Storm’ by��Sebastian Junger (1997)

Yeah, so we cheated. Try as we might, we couldn’t break the tie between these two blockbusters of disaster. Fact is, they’ve both outlasted their initial sensational appeal and one reason, we suspect, is that they’re stories of people confronted with great danger they did not seek. subjects members of a Uruguayan rugby team whose Fairchild F-227 crashed in the Andes in October 1972 had no intention of conducting a ten-week, cannibalistic survival course above timberline. Especially grisly aside from, yes, the consumption of “raw meat”��is the avalanche that buried the survivors on their 17th day stranded.��Read gives a paragraph or more to each man, and you may have to remind yourself to inhale: “Pedro Algorta, still buried beneath the snow, had only what air he held in his lungs. He felt himself near to death, yet the knowledge that after his death his body would help the others to survive instilled in him a kind of ecstasy. It was as if he were already at the portals of heaven.”

were out trying to make a living when a “once in a century”��nor’easter hit in October 1991, and their hard luck deepens this account of their loss. Perilous work is Junger’s grand theme, and his abiding respect for it enables him to go beyond the events at hand, whether deciphering complicated meteorology or reporting the angry sorrow of wives and brothers seeking justice that isn't coming. In the paperback, eager to get it right, Junger cleared up controversies surrounding his facts, but he’d already taken what could have been a maudlin story and banged it into a thriller.

22. ‘My Journey to Lhasa’ by��Alexandra David-Neel (1927)

Frankly, she’s not in the demographic. She’s 54. She's stout. She’s a former opera singer, for crying out loud. Who cares? A scholar of Eastern religion and Tibetan language, David-Neel was indisputably a fearless traveler, a rogue’s rogue who, in 1923, disguised as an illiterate pilgrim, became the first Western woman to reach Tibet’s forbidden city.

Mind you, doesn’t reinvent the form. David-Neel sets down what happened in the order it happened, and her attention to detail is almost anal. She even has the requisite adventure sidekick, a young Sikkimese monk. An unlikely pair, they’re stuck together in an escapade that involves everything from fooling the locals with their disguises to crossing 19,000-foot passes at night. “Was the lama far behind?”��she writes. “I turned to look at him. Far, far below, amidst the white silent immensity, a small black spot, like a tiny Lilliputian insect, seemed to be crawling slowly up. … An inexpressible feeling of compassion moved me to the bottom of my heart. … I would find the pass; it was my duty.”

David-Neel’s prose is of its time, in the best and worst ways, but her account has the power to awe even today.

21. ‘Kon-Tiki’ by��Thor Heyerdahl (1950)

“Just occasionally you find yourself in an odd situation. You get into it by degrees and in the most natural way but, when you are right in the midst of it, you are suddenly astonished and ask yourself how in the world it all came about.”

, the very prototype of the seemed-like-a-good-idea-at-the-time fool’s errand. Heyerdahl, of course, set out on a balsa raft in 1947 to prove that the South Pacific could have been peopled by natives of Peru. Along with five equally loco Norwegians and a parrot, he survives on fish that literally hurl themselves on deck, meets up with a few sharks, and endures a beaching in Tahiti. Though the trip proved inconclusive (to say the least), it created such a sensation that lecture halls around the world sold out for debates on Polynesian history. Heyerdahl’s antics can have a hand-me-down quality, something vaguely remembered from seventh-grade social studies, but just because everyone’s supposed to read him doesn’t mean he’s not great company. Heyerdahl’s happily aware that his is an absurd cosmic prank, but it’s still one heck of a story of men and the sea.

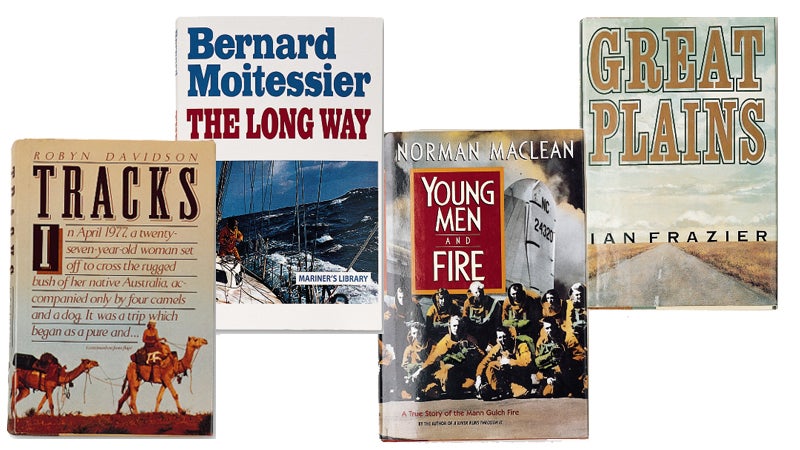

20. ‘Great Plains’ by��Ian Frazier��(1989)

Talk about a road trip: Frazier begins with an ode reminiscent of Whitman. “Away to the great plains of America, to that immense western short-grass now mostly plowed under!”��and ends with 65 wonderful pages of notes on everything from Dodge City’s other nicknames (Bibulous Babylon of the Frontier) to how Native Americans used their bodies as alarm clocks by drinking lots of water before going to bed. In between, he cruises from the Black Hills to Turkey, Texas, holding forth with visionary zeal: “Personally, I love Crazy Horse,”��he writes, “because, like the rings of Saturn, the carbon atom, and the underwater reef, he belonged to a category of phenomena which our technology had not then advanced far enough to photograph.”��Sure, we fought over whether Frazier packed enough red-blooded adventure into this book to make the cut. He gets around mostly by car, so we might just as easily have tapped Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley, or Least Heat-Moon’s Blue Highways, or gone straight for the source of our adolescent wanderlust with On the Road. Well, we could have, and we didn’t. Not because we don’t love those other asphalt serenades, but because Great Plains both delivers a song of the open road and defibrillates the heartland like no book we know.

19. ‘Young Men and Fire’ by��Norman Maclean��(1992)

Maclean may be best known for the novella and short stories collected in A River Runs Through It, but the nonfiction , an unfinished work written in his “antishuffleboard”��years and published two years after his death, has every bit the passionate following River did before Redford brought it to the screen. In many ways, this is the original smoke-jumper story, reopening the file on one of the worst firefighting disasters in history, the Mann Gulch Fire of 1949. Some of the earliest jumpers chuted in and set to work on the massive Montana blaze not far from Maclean’s cabin; two hours later, 12 of the 15 had been burned “like squirrels.”��By turns intensely beautiful, rarely is something so dangerous rendered so lyrically and exquisitely erudite on the physics of fire. Maclean’s affecting book is full of taut passages that jack your pulse rate as the men try to outpace the runaway blaze. “The grass and brush of Mann Gulch could not be faster than it was now,”��Maclean writes, as the smoke jumpers realize they are hemmed in by a ridge. “It could run so fast you couldn’t escape it and it could be so hot it could burn out your lungs before it caught you.”

18. Running the Amazon,��Joe Kane��(1989)

As ��opens, our man Kane is something of an �����ԹϺ��� Everyman. He’s been editing a newsletter for the Rainforest Action Network; he arrives in the Andes toting a copy of The Portable Conrad; he's joking about being shot at by the Shining Path. (Soon enough this won’t be a joke.) He’s also the only American among nine men and one woman attempting the first descent of the Amazon. Not a splashy writer so much as a sharp one, Kane starts slowly but soon has you gulping down chapters the way the team knocks back pisco: “At the beginning at least, whitewater adrenaline comes cheap. It’s the river doing the work, of course, but like a teenager with a hot car, one forgets what the true power source is. Arrogance reigns. … You think: Let’s get on with it.”��And Kane does, observing how arrogance gets chastened to humility��and noting each snag of dysfunction in a team of which only four go the distance. It’s that combination of interpersonal struggle and poignant scenes of life on the river that elevates Running the Amazon above the deluge of first-descent books. That and the fact that he had 4,200 miles of material to work with.

17. ‘The Long Way’ by��Bernard Moitessier��(1971)

“When you have long skirted vast expanses stretching to the stars, beyond the stars, you come back with different eyes.”��, contemplating his return to dry land after ten months on the open ocean. We love this book because of its sheer boldness: At the head of the pack in the 1968 Golden Globe, the first round-the-world solo yacht race, the author passes up the chance to claim victory and just keeps going. Moitessier ultimately puts ashore in Tahiti, having slingshotted a farewell note aboard a passing ship and jettisoned his clothes and many cases of good red wine along the way. At sea the Frenchman is a holy fool, disillusioned by society and reluctant to let go of the ineffable feeling of well-being he gains at sea. There are any number of supposedly more gripping, can’t-put-it-down seafaring stories (see the sad tale of his fellow racer Donald Crowhurst on page 65), but we challenge you to find one more appealing than Moitessier’s thoughtful and high-spirited log. And that goes for the man who inspired him, Joshua Slocum, number seven on this list. It’s no coincidence that Moitessier named his 40-foot steel ketch Joshua.

16. ‘Tracks’ by��Robyn Davidson��(1980)

You read and think: I’ve had friends like you. Friends who fun tends to metastasize around. Friends you facetiously hate, because they blow into town and stage weekends it takes weeks to recover from. No question, she’s plumb crazy “gone tropical”��as she puts it but crazy in the best sense of the word. At 27, the young Australian arrived in Alice Springs with six dollars, trained two wild camels (you try it), and set off for the Indian Ocean with the semiferal dromedaries, two tame ones, and her dog. But behind the madcap drama of the “camel lady,”��as Davidson became known, are a young woman's complicated emotions about the end of adventure and the arrival of fame. Reaching the ocean after 1,700 miles, she “rode down that stunningly, gloriously fantastic pleistocene coastline with the fat sun bulging on to a flat horizon and all I could muster was a sense of it all having finished too abruptly, so that I couldn't get tabs on the fact that it was over.”��Just weeks later she’d be feted in New York, realizing that she “was forgetting that what’s true in one place is not necessarily true in another. If you walk down Fifth Avenue smelling of camel shit and talking to yourself you get avoided like the plague.”��Davidson is the world’s most reluctant darling but walking wild, ragged, and alone, she blew the dust off the tired, musty feet of white-male adventure.

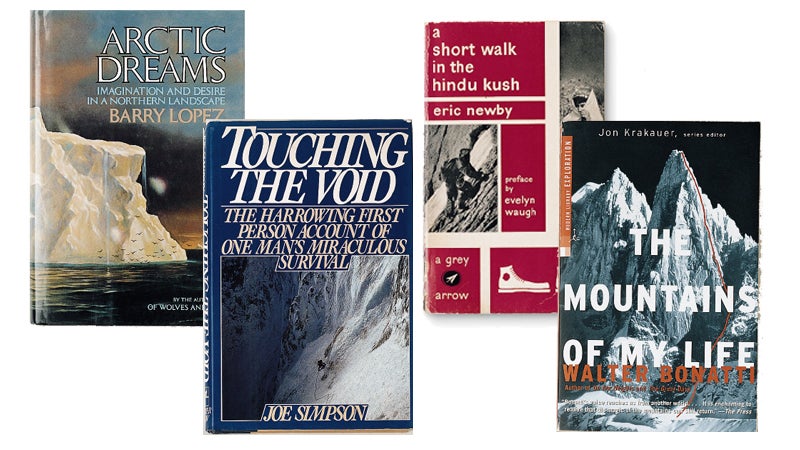

15. ‘A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush’ by��Eric Newby (1958)

“Newby to Friend: I’m bored. Let’s drive to Afghanistan and climb some previously unvisited peaks in the Hindu Kush.

Friend to Newby: Good idea, but we don’t know how to climb mountains.

Newby to Friend: Not a problem. We’ll go to Wales for the weekend and learn how.”

That’s how Tony Wheeler, the founder of Lonely Planet and the proud U.S. publisher of , summarizes this droll classic, the original buddy flick of Extreme Lit. Without Newby, there might never have been a Bryson, an O’Hanlon, or a Cahill. He’s the backpacker without a cause, the sort who gives himself over to the journey a quite ambitious trek through Afghanistan’s rugged Nuristan region certain that only by blundering forward can the purpose of the excursion be revealed. Newby reminds us that even a valid passport is inessential to traveling. All you really need is to be game.

14. ‘Arctic Dreams’ by��Barry Lopez (1986)

Thanks to fellow badass Edward Hoagland’s glowing New York Times review, critics couldn’t seem to refer to without the word “jubilant,”��which, from a certain perspective, is curious. After all, close encounters with polar bears, killer whales, and walruses, while thrilling, aren’t necessarily joyful, and tend to make the author, by his own confession, rather anxious.

“It is not all benign and ethereal at the ice edge,”��Lopez writes. “You cannot I cannot lose completely the sense of how far from land this is. I am wary of walrus. … A friend of mine was once standing with an Eskimo friend at an ice edge when the man cautioned him to step back. They retreated 15 to 20 feet. Less than a minute later, the walrus surfaced in an explosion of water where they had been standing.”

Lopez may feel inexperienced, but it’s hard to imagine a better interpreter of the far north. His descriptions of the Arctic Ocean shine: “A geometry of lightning-bolt-shaped leads, of long black ponds, jagged rills, and ridges of debris that meander like eskers stretches as far as light and the atmosphere let you see.”��And come to think of it, though Arctic Dreams involves a great deal of solitude and icebergs and cold, jubilant is the word. Lopez leaves us amazed by the natural world, respectful of our place in it, and elated at its dazzling variety.

13. ‘In Patagonia’ by��Bruce Chatwin (1977)

We know what you’re thinking: Idiots, it’s fiction! But the claims that Chatwin lied to fashion the episodes and characters that make up this exquisite little book turn out to be greater exaggerations than Chatwin’s own. Sure, he got things out of order, mangled some Spanish, and dished up a few now classic Chatwinian embellishments (Se-ora Eberhard’s run-of-the-mill steel chair becoming a Mies van der Rohe, for one). But is at heart a personal quest to find the origins of boyhood fascination, “a piece of brontosaurus”��supposedly recovered from a thawed glacier in Punta Arenas by Chatwin’s seafaring cousin. At first Chatwin’s prose seems uniform like Hemingway, only boring. But his subtle sentences sneak up on you, and their economy allows him to surprise, leaving an indelible impression. Take Walter Rauff, exiled Nazi and inventor of the lethal Mobile Gas Truck: “There is a man in Punta Arenas, dreams pine forests, hums Lieder, wakes each morning and sees the black strait. He drives to a factory that smells of sea. All about him are scarlet crabs, crawling, then steaming. He hears the shells crack and the claws breaking, sees the sweet white flesh packed firm in metal cans. … Does he remember that other smell, of burning?”��Chatwin’s haunting images stay with you, reminding you that this is one messed-up, astonishing world.

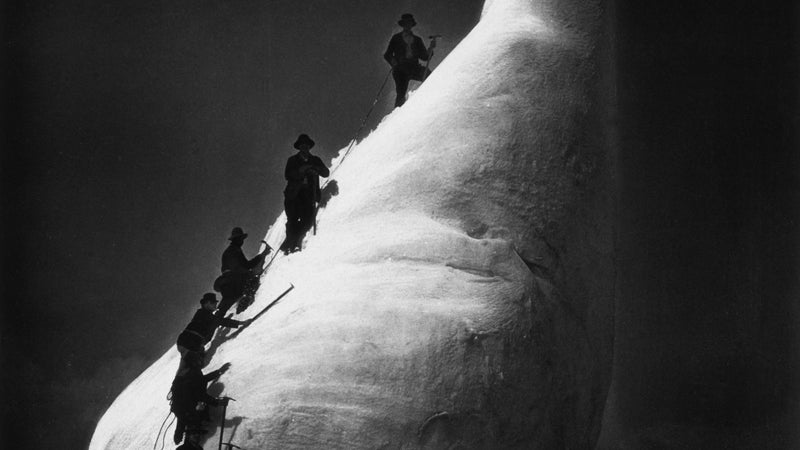

12. ‘The Mountains of My Life’ by��Walter Bonatti (2001)

finally published in the United States just two years ago take pride of place here over a number of towering works on mountaineering because (a) Bonatti was a god, a poetic soloist whose career included a controversial role in the first ascent of K2, and (b) he proves he can write as gracefully about a sunrise over the Alps as about an epic first ascent: “The horizon showed up sharply, enchanted peaks plucked clean by the claws of a freezing and frenzied wind,”��Bonatti says of his 1962 ascent of the Alps’��Pilier d’Angle. “When I looked out I saw the most beautiful spectacle one can encounter at dawn on the peak of Mont Blanc: on the one hand the Italian flank flooded with warm and blazing light, on the other the Savoie still immersed in night.”

Take nothing away from Gaston Rebuffat’s 1954 Starlight and Storm, the Frenchman’s spare and lovely tract that made the case for climbing as a communion with, rather than siege upon, mountains. And we know as well as anyone that Maurice Herzog’s canonical 1953 Annapurna was the Into Thin Air of its day, inspiring Ed Viesturs and countless other next-generation alpinists to take up climbing. But in returning to Annapurna we found we’d rather skip Herzog’s press-release nationalism and hang out with Bonatti.

11.��‘Touching the Void’ by��Joe Simpson (1988)

As mountaineering survival stories go, this is the destroyer of its class: an incredible climbing epic in the hands of a pitch-perfect writer. starts out as a journal about the solace (and menace) of going high and remote (Peru’s 21,000-foot Siula Grande) but soon becomes something else entirely. On the descent from the 21,000-foot summit, the author, suffering from a broken leg and damaged ribs from a previous accident, falls into a crevasse. His partner, Simon Yates, presuming him a goner and unable to keep Simpson’s dead weight from pulling him off the mountain, does the unthinkable: he cuts the rope. Alone in a canyon of ice, Simpson veers from stubborn determination to screaming anger and despair: “There was no one to hear,”��he writes, “but the looming empty chamber behind me made me feel inhibited, as if it were some disapproving silent witness to my weakness.”

The book’s device of interspersing the devastated Yates’s thoughts in italics makes for amazing reading, and the pair’s reconciliation three days later at base camp, after Simpson has dragged himself down the scree, is a scene and theme that rises far above the mountaineering genre. Present the ethics of this book to someone who's never climbed a mountain and you could still end up talking about it all night.

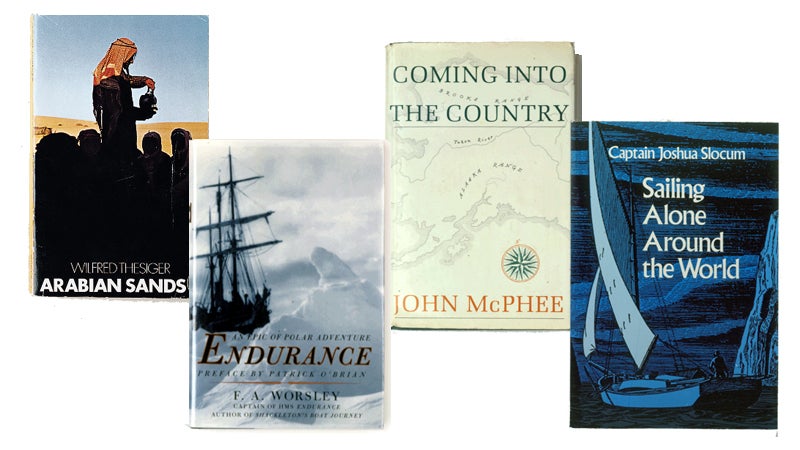

10. ‘Arabian Sands’ by��Wilfred Thesiger (1959)

The last great British explorer? Eric Newby, for one, might jokingly beg to differ, but that’s because Thesiger called him a pansy when they met in the Hindu Kush. Sir Wilfred, the now 92-year-old troubadour who explored Arabia’s Empty Quarter before the oil fields tamed Bedouin culture, valiantly resists the lame camel jokes made by so many of his contemporary countrymen and, in contrast to many of today’s travel diarists, rarely makes himself the subject of his own stories. Thesiger’s love of the desert is never easy, always hard-won. “I climbed a slope above our camp and bin Kabina joined me. I was hungry; I had only half my portion of the ash-encrusted bread the night before. The brackish water which I had drunk at sunset had done little to lessen my nagging thirst. Yet the sky seemed bluer than it had been for days. The sand was a glowing carpet set about my feet.”��For us, the question was merely, Which Thesiger? Yes, Marsh Arabs may be, as some critics claim, the better book, but is electric. And sure, we love those pithy quotes from T. E. Lawrence’s The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, but we’re in no mood for that bombast cover to cover. Stick with Thesiger: he’ll make you wish you were born 50 years earlier and could make the trips he did with him.

9. ‘Coming into the Country’ by��John McPhee (1976)

Like Thesiger, there’s no question that McPhee belongs on this list the struggle comes in choosing which book. We were charmed by the slightly obscure Survival of the Bark Canoe. And certainly we heard from those who agitated for Encounters with the Archdruid, about environmental guru David Brower. But in the end our vote went to . Drawing on a marathon canoe trip down Alaska’s Salmon River and a season in a cabin on the Yukon River, McPhee knits together a passion for the backcountry, an unsentimental yet stirring view of Alaska’s Native tribes, and a hard look at the many misguided attempts to manage the Last Frontier’s natural resources (with a brilliant recap of the pipeline saga). McPhee pretty much tackles all the big questions here: “To a palate without bias—the palate of an open-minded Berber, the palate of a traveling Martian—which would be the more acceptable, a pink-icinged Pop-Tart with raspberry filling (cold) or the fat gob from behind a caribou’s eye?”

Really, no one has done a better job of combining ride-along backcountry hijinks and lucid parsing of enviro policy than McPhee does here. Four hundred thirty-eight pages, and nothing less than the fate of Western civ, on a canoe trip.

8. ‘Into the Wild’ by��Jon Krakauer (1996)

Is Into Thin Air the more influential book? Absolutely. Is it the more thrilling? Arguably. However, not only is Into the Wild more arrestingly written and reported than its more famous cousin, it also stands up better to rereading. And whereas Into Thin Air delivers a stinging indictment of what’s wrong with modern mountaineering including ill-prepared individuals trying to “buy”��the world’s summits,��, which follows the final days and nights of a young idealist named Chris McCandless, speaks to anyone who has ever yearned for something pure, to be free of the affluenza of American life, to be self-reliant.

Like Into Thin Air, Into the Wild began as an article in �����ԹϺ���. But the book combined that investigation with material from new sources, people McCandless had met en route to Alaska who were brought out of the woodwork by the article. One of those whom McCandless touched most profoundly was Ronald Franz (not his real name), an 80-year-old so taken with the young man that he waited at McCandless’s campsite in the desert near the Salton Sea for his return.

From the accounts of people like Franz to close readings of McCandless’s underlined copies of Doctor Zhivago and Walden (“No man ever followed his genius till it misled him”), Krakauer not only gets why McCandless retreated to the bush, but makes use of his own backcountry experience to empathize with him. Some readers have suggested that Krakauer is too easy on the kid and that McCandless ought to be viewed as suicidal, manipulative, or ridiculous, but Krakauer keeps it all an open question. Into the Wild reminds us that the very qualities of being in the wilderness that thrill and restore us or lead us, as Roderick Nash wrote, to “either melancholy or exultation”��can swiftly take our lives.

7. ‘Sailing Alone Around the World’ by��Captain Joshua Slocum (1900)

A century later, Slocum’s account of the first-ever solo circumnavigation of the earth, and then some, on his 37-foot sloop, Spray, remains the title by which all other sailing books are judged not only because of its derring-do��but because it’s completely winning. “The day was perfect, the sunlight clear and strong,”��Slocum writes. “Every particle of water thrown into the air became a gem, and the Spray, making good her name as she dashed ahead, snatched necklace after necklace from the sea, and as often threw them away.”��Few contemporary sailing accounts come close to matching Slocum’s logs, not least for the captain’s sly wit: “Some hailed me to know where away and why alone. Why? … The shore was dangerous!”��This coming from a man who'd previously suppressed a mutiny and survived an ocean storm in a canoe. only improves with age, because reading it is like being present at the creation of the modern explorer-adventurer. Thoreau may have convinced us to return to the wild; Slocum revealed how that journey could be a feat of endurance, and a lighthearted spectacle to boot. If only the multitudes who followed his example did so on the page. Slocum never sells you on his story; he just tells it.

6. ‘Endurance’ by��F. A. Worsley (1931)

First off, he was there. Sure, Alfred Lansing’s 1959 has stood the test of time as a journalist’s chronicle, and Caroline Alexander broke new ground four years ago with her own The��Endurance’s comprehensive retelling of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s epic survival story. But as captain of the real HMS Endurance and navigator of the lifeboats he and Shackleton used to effect a rescue across the Southern Ocean, Worsley proved himself not only one of the finest small-craft sailors of the 20th century, but also a less official, more anecdotal, and��ultimately��more electrifying diarist than Sir Ernest himself.

By now��most people know this story down to the last dog and cat, but the immediacy of Worsley’s account revitalizes it. If you don’t feel his sorrow in losing his ship to the ice pack, share his delirium glissading down to the South Georgia whaling station that would be their salvation (a scene to which Shackleton, ever careful not to seem whimsical, gives only a cursory line in South), or tear up when the two men return to their friends on Elephant Island 128 days after they set out, you don’t love adventure.

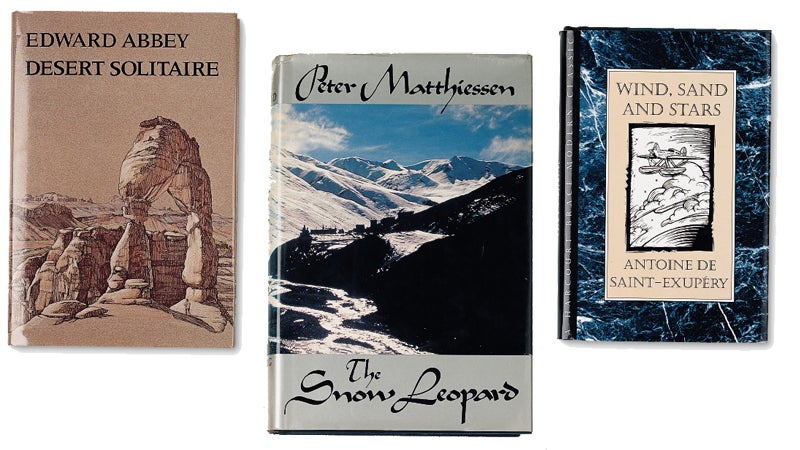

5. ‘Desert Solitaire’ by��Edward Abbey (1968)

Obviously.

Four decades and change later, Cactus Ed is still Iggy Pop in a stale world of environmental classic rock. So punk that it transcends the natural history genre, of two seasons spent as a ranger in Arches National Park is about soul-searching, but without an ounce of New Age squish. “I dream of a hard and brutal mysticism in which the naked self merges with a non-human world and yet somehow survives still intact, individual, separate. Paradox and bedrock.”��Argue with that.

4.��‘The Snow Leopard’ by��Peter Matthiessen (1978)

Simply put,�� gets to the heart of why we go to the mountains. There are many other fine books on the subject John Muir’s My First Summer in the Sierra comes to mind but none succeed, as Matthiessen’s does, on so many levels.

One could say, for example, that it’s a book about sheep. After all, it delivers a funny, anecdotal account of American zoologist George Schaller’s field research on the Himalayan blue sheep, or bharal. (“Oh, there’s a penis-lick!”��G.S. cries out, observing the rut. “A beauty.”) Then there’s the mythic cat of the title, which had been glimpsed by only two Westerners when Matthiessen and Schaller set out to track it in 1973. And the place the mysterious Land of Dolpo, a last enclave of Tibetan culture. And finally, without ever becoming a book about recovery, The Snow Leopard charts how the author came back to life after a great loss his wife, Deborah, had died of cancer the year before he left for the Himalayas. “Why is death so much on my mind when I do not feel I am afraid of it?”��Matthiessen asks��while walking a sheer Himalayan ridge. “Between clinging and letting go, I feel a terrific struggle. This is a fine chance to let go, to ‘win my life by losing it.’”

3. ‘West with the Night’ by��Beryl Markham (1942)

Sure, Markham starts a touch self-consciously, wondering aloud where, in the blur of her career as a pilot in Kenya during the 1930s, she ought to begin this tour de force memoir. But if you haven’t forgiven her this slightly contrived opening in three or four pages, we’d be surprised. The essence of a fascinating party guest, Markham is not only charming��but full of real adventures to tell from being mauled by a lion at age seven and nearly trampled by an elephant as an adult to bringing game hunters into (and, happily, back out of) the wild. Equally adept at telling a nail-biter as she is at waxing poetic about an African horizon or making you sorry her dog got gored by a warthog, you discover early and often why Hemingway gushed that she made him feel inadequate as a writer. “The only disadvantage in surviving a dangerous encounter,”��she observes, “lies in the fact that your story of it tends to be anticlimactic. You can never carry on right through the point where whatever it is that threatens your life actually takes it and get anybody to believe you. The world is full of skeptics.”��Markham is one of the few authors you are nearly always grateful to have as the hero of her own stories. , but be prepared to fall in love with a ghost.

2. ‘The Worst Journey in the World’ by��Apsley Cherry-Garrard (1922)

So many superlatives have been heaped on this sick pup that it’s hard not to feel a little jaded before you read it for yourself. Don’t let the hype or, for that matter, the dozens of other books on Robert Falcon Scott’s doomed 1911 South Pole expedition scare you off. Livelier than Scott’s own writings (collected in Scott’s Last Expedition) and more immediate than Roland Huntford’s modern classic The Last Place on Earth, of this infamous sufferfest is a chilling testimonial to what happens when things really go south. Many have proven better at negotiating such epic treks than Scott, Cherry, and his crew, but none have written about it more honestly and compassionately than Cherry. “The horrors of that return journey are blurred to my memory and I know they were blurred to my body at the time. I think this applies to all of us, for we were much weakened and callous. The day we got down to the penguins I had not cared whether I fell into a crevasse or not.”

1. ‘Wind, Sand, and Stars’ by��Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (1939)

Like his most famous creation, The Little Prince, that visitor from Asteroid B-612 who once saw 44 sunsets in a single day, Saint-Exupéry disappeared into the sky. Killed in World War II at age 44, “Saint Ex”��was a pioneering pilot for Aéropostale in the 1920s, carrying mail over the deadly Sahara on the Toulouse-Dakar route, encountering cyclones, marauding Moors, and lonely nights: “So in the heart of the desert, on the naked rind of the planet, in an isolation like that of the beginnings of the world, we built a village of men. Sitting in the flickering light of the candles on this kerchief of sand, on this village square, we waited out the night.”��Whatever his skills as a pilot—said to be extraordinary—as a writer he is effortlessly sublime. is so humane, so poetic, you underline sentences: “It is another of the miraculous things about mankind that there is no pain nor passion that does not radiate to the ends of the earth. Let a man in a garret but burn with enough intensity and he will set fire to the world.”��Saint-Exupéry did just that. No writer before or since has distilled the sheer spirit of adventure so beautifully. True, in his excitement he can be righteous, almost irksome like someone who’s just gotten religion. But that youthful excess is part of his charm. Philosophical yet gritty, sincere yet never earnest, utterly devoid of the postmodern cop-outs of cynicism, sarcasm, and spite, Saint-Exupéry’s prose is a lot like the bracing gusts of fresh air that greet him in his open cockpit. He shows us what it's like to be subject and king of infinite space.

Personal Canon

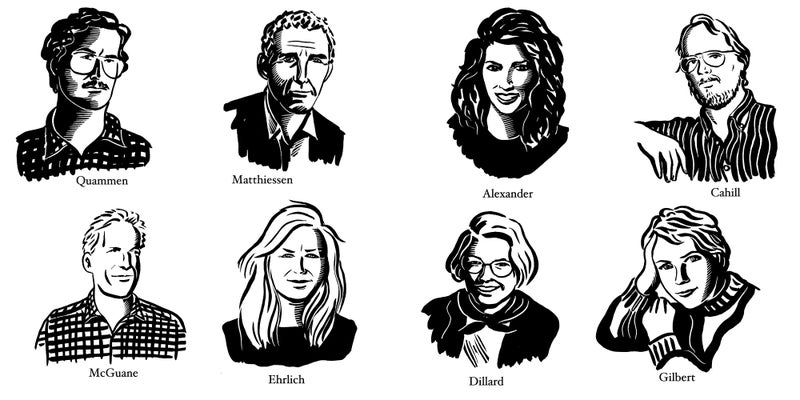

Authors sound off on the books that have stuck with them

‘Travels in West Africa’ by Mary Kingsley (1897)

I first came across in a library. I sat down on one of those plastic ladders and thumbed through the book, and by the time I reached the checkout desk, I’d decided to retrace her footsteps.

Although Travels in West Africa was published in 1897, Kingsley’s humor and sensibility are extraordinarily modern. She started out a very sad woman, a spinster. (In the movie, she’d be played by Emma Thompson.) Her contemporaries wrote books in which a hero, bent on a specific goal, triumphed over��or was defeated by��geography. But for Kingsley, the journey—a ramble from Sierra Leone to the “Great Peak of the Cameroons”—was the story. And the Africans she met were not merely guides, porters, or villagers, but characters she brought to life as individuals. Hers is a journey about discovery, not just about getting from A to Z, and it is filled with insights.

Kingsley was my companion when I went to West Africa in 1987. I carried her book everywhere, and people were always thrilled to see the name of their village in print. But one old man asked me, as if he were facing down an impostor, “If you were here all those years ago, what are you doing here now?”��—Caroline Alexander, author of The Endurance

‘My Side of the Mountain’ by��Jean Craighead George (1959)

I can’t have been the only kid who was inspired by ��to stalk imaginary deer during those short hours between piano lessons and dinner, can I? The story is simple: a��city boy named Sam Gribley runs away to the country, lives in a tree trunk, and survives the winter. My sister and I took the book seriously enough to turn it into a game. After school��we’d run out to the woods behind our house and pretend to live in a hollowed-out tree, getting by on a diet of nuts and berries. Our game really wasn’t all that different from the one my parents were playing—returning to the farm, trying to live off the land. It was the seventies, after all. But the best thing was that it took us out of the world of obligations. Even as kids you have chores; what Sam had was absolute freedom. He didn’t have to write an essay on the birds of America—he had a pet falcon! I think that’s still true, even for us grown-ups, this desire to get back to a natural state. I just spent ten days hiking in the White Mountains with my dad, and it was great. We were free from obligations the whole time.��—Elizabeth Gilbert, author of

‘Grass Beyond the Mountains’ by��Richmond P. Hobson Jr.��(1978)

��is the true story of a young man from New York whose business expectations were crushed by the Depression. He headed west, where he became a skilled cowboy. In Wyoming he paired up with a mysterious character, probably a rustler, and the two of them drove in a dilapidated sausage truck to remotest northern British Columbia to start a cattle operation. It was an adventure that should have killed them both, but somehow they succeeded.

Hobson had the most wonderful capacity to convey the natural marvels of that land. He utilized his wide horizon of reference to capture the magic of the country, and in so doing gave us a glimpse of something now gone. The perils of enduring winter in such an implacable landscape are described vividly. The horses had to be tough, and the horsemanship was remarkable. There were cattle drives in blizzards so extreme that cowboys went blind, but the horses got them through. Grass Beyond the Mountains makes a reader wish that he had been there, and vastly relieved that he was not. —Thomas McGuane, author of

‘Dersu the Trapper’ by��V. K. Arseniev��(1923)

��is one of the great travel classics and a book that astounds everyone who reads it. Starting in 1902, the Russian explorer V. K. Arseniev traveled throughout the Far East, mapping an untouched corner of Siberia between Manchuria and the Sea of Japan. This is remarkably rugged yet beautiful country, where wolves, leopards, tigers, and bears are all in one place. It was here that Arseniev met and was befriended by Dersu, an indigenous hunter-trapper of the Tungus-Manchu tribes. I know the area well, having worked there while researching my book Tigers in the Snow. In a way, Dersu the Trapper was an inspiration for me. Filmmakers had approached me to write a script based on Dersu, but it was during the Cold War, and because the area they hoped to film in was close to Vladivostok, the permit was denied. When I finally received a permit��years later, I went to track the Amur tigers.

Arseniev wrote in Russian, and the first American edition did not appear until 1941. It is beautifully written, full of evocative material, and has wonderful illustrations drawn by Arseniev himself. As it turns out, there’s a museum dedicated to Arseniev in Vladivostok. It's a little bit of the old Soviet Union, though. The tigers could use a dusting.��—Peter Matthiessen, �����ԹϺ��� contributor and author of

‘The Island Within’ by Richard K. Nelson (1989)

Richard K. Nelson is a very great—if not the greatest—nature writer we have. Other nature writers agree on his magnificence, which ��established in 1989. What a book.

Nelson is sort of in the position Cormac McCarthy occupied 15 or 20 years ago. Other writers read his stuff—Blood Meridian above all, and Suttree for people southern enough to see how funny it is—but general readers were ignorant until All the Pretty Horses came out and his loyal publishers decided to make a fuss.

I’d not heard a word about The Island Within; it’s not the sort of thing I read, and the opening made me cringe: a��guy and his dog go to an island off the Alaskan coast for the purpose of—oh, no!—self-discovery. How awful that this concept was a pandemic now affecting men. Why did I keep reading?

Well into the book, I found an episode that was so sublime—I won’t wreck it for you—a story told so intelligently,��and so powerful as imagery, I thought, He can’t keep this up. He should have saved it for last.��The next chapter topped it. The following chapter topped that. And so on! He had achieved escape velocity and was winging it out in the old empyrean with only the very great ones for company. All this, mind you, right on the surface, relating incidents on the island, like a bald eagle’s swimming in the sea. He bore us out to the pillars where stars condense. Anyone can see stuff and learn facts; it’s what you make of it. His rhetorical pitch was as wild as Thoreau’s on Katahdin, transporting as Shakespeare pushing art into the realms that ennoble the reader. I finished The Island Within out of breath.

Then I checked the jacket copy. (Read it last or not at all.)��Turns out I had read Richard K. Nelson before. He was a true cultural anthropologist of the sort that sociobiology had tried to gun down. He had written Hunters of the Northern Ice, about the Inuit, which I loved. How did he get a readable dissertation past his committee?

And it was Nelson who wrote Make Prayers to the Raven (1983), which I had avoided for a stupid reason: its title reminded me of I Heard the Owl Call My Name, a moving little book I found only OK. But after reading The Island Within, I got Make Prayers to the Raven, knowing I wanted to read everything Nelson wrote.

Its subtitle is A Koyukon View of the Northern Forest. The Koyukon Athapaskans are still living intimately with their vast lands in interior northwest Alaska—right now—and if it bothers you that they use snowmobiles, motorboats, and rifles, too bad—they aren’t a theme park. Their knowledge and thinking differ from ours more than a spear differs from a rifle. Nelson lived with Koyukons and learned their ways, their animating beliefs, and their biology. They live in a mesh of taboos, which Nelson respects. The animals have religious taboos, too. A woman told him that “gestating female beavers will not eat bark from the fork of a branch, because it is apparently tabooed for them.”��She was not putting Nelson on; she learned this from her grandfather. Did it never strike reasonable people that a beaver can’t fit its head in a narrow fork? Maybe taboo started out meaning “stupid,”��as in, “It is stupid to get your sister pregnant.”

These are three wonderful books, and there are more. The Island Within is a masterpiece. Ask any nature writer. Like everyone else, we hate being typed. (Peter Matthiessen's a great novelist.) You almost have to hold a gun at my head to make me read “nature writing,”��but I’ll crawl over broken glass for Richard K. Nelson.��—Annie Dillard, author of

‘The Farm on the River of Emeralds’ by Moritz Thomsen (1978)

In late��1978, �����ԹϺ��� proudly published an excerpt from . I thought the book read like the best of Joseph Conrad, only funny. Thomsen, at 53, had returned to work a farm in Ecuador, where he’d served with the Peace Corps in the 1960s. We see how poverty twists and distorts people and places. We sit with him as he listens to opera and watches vast thunderstorms roll over the land. We cringe at a reflective honesty that spares no one, least of all the author himself. And then we learn of Arcario Cortez, who, on his honeymoon, made love to his new wife eight times in eight hours: “He was another Sir Edmund Hillary who—without ropes or tanks of oxygen or snacks of cheese or chocolate, without Sherpa guides or sponsorship from the National Geographic Society, all on his own with nothing but youthful grit—now stood alone on his solitary peak, every bit as exhausted and triumphant as Hillary himself.”��Thomsen died in Ecuador in 1991. He had written four books, all brilliant, but I think The Farm on the River of Emeralds is his masterpiece. Naturally, it is out of print, a tragic circumstance that would have amused Thomsen to no end.��—Tim Cahill, author of

‘Eyelids of Morning: The Mingled Destinies of Crocodiles and Men’ by��Alistair Graham and Peter Beard��(1990)

is the most wonderfully lurid coffee-table book ever assembled. It’s also a far-ranging meditation on the role of man-eating reptiles in human history and psychology, and a vivid account of a valuable, difficult, bloody scientific study. Over the past three decades it has been out of print, hard to find, impossible to find, venerated as an underground classic, and then back in print. It's currently out of print but findable.

Alistair Graham was the biologist of the team; Peter Beard took the photos and designed the book. Together they spent a year on Lake Rudolf (now called Lake Turkana) in northern Kenya, killing and dissecting about 500 animals in order to learn what they could about Crocodilus niloticus, the Nile crocodile. At that time (1966–68) Graham was a hard-headed young scientist with a visceral admiration for crocodiles and no patience whatsoever for sentimentalizing them. He did some other intriguing work and then, it seems, disappeared. I’ve been trying to locate him for three years, in connection with a project about big predators. No luck. I’ve traced him from Africa, heard he worked as a chauffeur in England, and found folks who knew him as manager of a crocodile farm in northern Australia. Then the trail goes cold. Alistair, if you’re reading this: Great book! And please call me.��—David Quammen, �����ԹϺ��� editor at large and author of

‘Across Arctic America’ by Knud Rasmussen (1927)

During his nearly three-year dogsled journey (1921–24) from Greenland to Point Barrow, Alaska, explorer Knud Rasmussen amassed roughly 6,000 pages of field notes that were condensed in 1927 into . When I first went to Greenland in 1993, I took an old, out-of-print copy. It was like holding living history. Rasmussen lived in igloos and houses made of stone, bone, and turf, and his descriptions of the white landscape, and of life on the ice—where you got around by sled only, lived by the light of seal-blubber lamps, and hunted and ate whales—excite the imagination.

In spring, when there is round-the-clock light and it's difficult to sleep, the Inuit I was dogsledding with would ask me to read passages aloud, even though they couldn't understand my English version. They all knew about Rasmussen, though, and loved to listen. “Give me dogs, give me winter,”��he wrote, “and you can have the rest.”��—Gretel Ehrlich, author of

Lost Horizons

Ten great books you’ve probably never heard of

‘Uttermost Part of the Earth’ by��E. Lucas Bridges��(1948)����

Bridges belonged to one of the first European families to land and hang on for dear life in Tierra del Fuego. (now��sadly��out of print) recalls the adventures that he and his kin endured, usually under such detached headings as Some Observations Concerning Cannibalism��and Instances to Show That the Cow Is More Intelligent Than the Horse.��Once you’re in, you see why Yvon Chouinard presses this book on first-time trekkers to Patagonia.

‘No Picnic on Mount Kenya’ by��Felice Benuzzi��(1953)��

Think��The Great Escape��meets��Life Is Beautiful. From the moment he lays eyes on the looming 17,160-foot peak, Benuzzi’s determined to climb it. Problem is, he’s an Italian soldier sitting out World War II in a British POW camp in Kenya. No worries; he breaks out anyway and heads up the mountain without a map. remain intact, even when he comes down and is thrown back in the clink.

‘The Ascent of Rum Doodle’ by��W. E. Bowman (1956)��

If this,��the definitive, of the conquest of “the world's tallest mountain”��fails to leave you gasping for oxygen from all the laughter, see a therapist. A brilliant send-up of self-important peak-bagging gas.

‘The White Spider’ by��Heinrich Harrer��(1959)��

Brimming with the suspense and history surrounding his pioneering ascent of the north face of the Eiger in 1938, is a surpassing meditation on the “supreme testing place of a man’s worth as a human being.”��Harrer packs every page with reasons why even gazing on the Eiger, much less dangling from its ramparts, makes your palms sweat.

‘The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst’ by Nicholas Tomalin and Ron Hall��(1970)��

An of one man’s ill-fated entry into the first round-the-world solo yacht race in 1968. Crowhurst comes unhinged in the Atlantic after falsifying reports about his progress, and then proceeds to lose his way, his mind, and��finally��his life.

‘Mawson’s Will’ by��Lennard Bickel (1977)��

It’s hard to keep a straight face reading what Aussie explorer in Antarctica the same year as Scott—it’s just so grim. The first of his two comrades plunges with his dog team into a bottomless crevasse. The second succumbs to snowblindness, frostbite, madness, and a coma. Alone, Mawson faces 100 miles of wind, ice, and starvation before he makes it back, his mind and limbs barely intact.

‘The Shining Mountain’ by��Peter Boardman (1982)

inside the brains of hardcore alpinists. Motivated to “bring my self-respect into line with the public recognition”��after topping out on Everest in 1975, the author hooks up with Himalayan vet Joe Tasker to climb the west wall of Changabang in India. Somehow they live to tell the tale.

‘Chasing the Monsoon’ by��Alexander Frater��(1990)��

begins in a doctor’s office in London, with the author wearing an orthopedic collar that makes him “look like a bulging pantomime frog.”��It ends in Cherrapunji, India, with Frater utterly soggy but loving life, after having taken a stranger’s advice to experience monsoon season on the subcontinent. You’ll feel better, too, for tagging along.

‘To Timbuktu’ by��Mark Jenkins��(1997)��

With three friends in tow,�������ԹϺ���’s own Hard Way columnist the Niger River. They make it down, and along the way encounter the menacing African welcome wagon—Killer bees! Guinea worms! River blindness! Rhinos! Crocs! But Jenkins never lets the tough stuff (or tense group dynamics) overpower the beauty of the land he floats through.

‘An Unexpected Light’ by��Jason Elliot��(1999)����

of his travels through war-torn Afghanistan nail-biting excursions with mujahideen deep inside mountain caves and up gorgeous slopes flecked with land mines is so exquisite, it sometimes masks the ancient danger lurking in the black heart of one of the world's most forbidding regions.

To Tell the Truth

Is it fact or is it fiction? The perplexing story behind .��By��Patrick Symmes

“You won't believe this one,”��my oldest friend said as he handed the book to me last year.

The slim but powerful volume was The Long Walk, by Slavomir Rawicz, a cult classic of adventure writing. First published in Britain in 1956, it chronicles how Rawicz, a 25-year-old Polish cavalry officer, broke out of a Soviet labor camp in Siberia in the midst of World War II and ran for his life. With six companions, he trekked 3,000 agonizing miles across Asia, passing through Mongolia, war-torn China, and Tibet before reaching freedom in British India.

Rawicz dictated his story to a Fleet Street ghostwriter in a direct, understated voice that puts his hardships in staggering relief. Despite gritty suffering in deserts and fatal setbacks in icefields, the fugitives struggle southward month after month, surviving on solidarity and sheer guts. The book’s triumphant but bitter ending leaves readers exhausted; legions of fans offer testimony on Amazon and other websites to the life-changing inspiration of Rawicz’s heroism. Once out of print, the book now sells 30,000 copies a year��and has been reissued with a new introduction by Sebastian Junger. George Clooney’s name has been thrown around to play Rawicz in a movie adaptation.

But ever since the book’s first release, doubters have charged that The Long Walk is literally unbelievable, even a fraud and a hoax. British climber and expedition leader Eric Shipton reputedly hooted at the book’s description of abominable snowmen; Hugh Richardson, Britain’s longtime diplomat in Lhasa, cited dozens of errors in a 1957 review for the Himalayan Club Journal��and wondered “whether the story is a muddled and hazy reconstruction of an actual occurrence, or mere fiction.”

I myself learned all this later, after I devoured The Long Walk with stunned enthusiasm. In retrospect, it does seem odd that Rawicz’s Mongolians walk everywhere rather than ride horses, and dress in conical hats and pole their boats up meandering rivers; that sounds more like Vietnam. Rawicz describes going 12 days in the Gobi without water; I recall choking on dust there myself after just a few hours. And I didn’t know what to make of Rawicz’s story of meeting two yetis in the high Himalayas.

Rawicz stood by his story. But his London and American publishers both told��me they don’t believe that every page of the book is strictly what the cover calls a “True Story.”��Rawicz has declined to produce records, photographs, witnesses, or the full identity and whereabouts of the other survivors.

Ghostwriters do embellish things. (Ask Marco Polo.)��Faced with deadly obstacles, men do manage to pull off the impossible. (Shackleton, anyone?)��And plenty of authentic adventurers have exaggerated their achievements. (Admiral Byrd, call your office.)��So while The Long Walk may never earn a secure place among the true classics of survival, here’s my advice: enjoy it as the great thriller it is. But caveat lector—which is Latin, of course, for “you won’t believe this one.”

To Hell and Back

Don’t cry for L. M. Nesbitt. (OK, maybe cry a little.) By��Bill Vaughn

I don’t read much expedition lit, preferring girl stories and dysfunctional melodramas to aggressive death-wish chronicles. But one night, weeping as I finished Jennifer Weiner’s , I wandered into my library looking for another tearjerker and found an adventure yarn so awful I couldn’t put it down.

“After some difficulty we succeeded in obtaining enough camels for our purpose.”��Thus begins L. M. Nesbitt’s relentless account of his 1928 expedition with two Italians through the chartless heart of Abyssinia, what is now called Ethiopia. One of the last installments from the jodhpur-and-pith-helmet school of British adventure (and currently out of print), ��is also its crankiest. Bribing his way 400 miles by caravan over the broasted wastelands of the Afar province, the arrogant 37-year-old Nesbitt is not amused by the locals. The “unruly”��Danakil tribesmen are by turns “sinister,”��“restless,”��and “slothful demons”��who appear to wear the dried testicles of their victims around their necks. Nesbitt reminds us—constantly—that no European has ever returned alive from the region. Like a hypochondriac announcing his pulse rate, he relates the soaring temperatures in the sulfur flats: 146 degrees, or 157, or 168. “Sitting half-stunned in the silence of this glowing furnace,”��he records in a style evoking the torpor of playing video games on Xanax, “we were like men struck motionless by the curse of fate.”

Nesbitt claimed the “purpose”��of his trip was to collect mineral samples, as he and his pals staggered in an endless fever dream from one dung-fouled water hole to another. But I didn’t buy it. So if he wasn’t after some mother lode, what compelled this mad Englishman to go out in the noonday sun? A book contract? A lecture gig at the Royal Geographical Society? Was he just not getting any at home? I kept turning the pages, anticipating the comeuppance that he so richly deserved. Alas, it never came. But the account became perversely more intriguing once I suspected that his maps were intended for the Italian generals who would command the 1935 invasion of Ethiopia. Indeed, a year after his ordeal, Nesbitt traveled to Rome with a present for Mussolini’s zoo: a crocodile snatched as a baby from the River Awash and carried across Abyssinia in a tin box.

When I finished those final lines, I laughed. And then I cried.