Get on a winning streak in Las Vegas and the mokes crowd around and act like they’re the lucky ones.

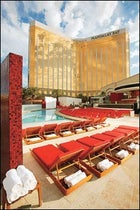

Mandalay Bay, Las Vegas

Mandalay Bay, Las Vegas

Mandalay Bay, Las VegasSo it goes one morning in the backstage depths of Shark Reef, the splashy aquarium exhibit that draws a million-plus visitors a year to Mandalay Bay, the tropical-themed casino resort on the south end of the Vegas Strip. Here, inside a clear 20-gallon tank, two little fish get lucky in the lewd sense. The male, an inch long, with iridescent blue patterning and flouncy, dark-edged fins, dogs a less flashy female that now and again lets him squeeze close and vibrate.

Each look at fish hey-hey increases the joy and fulfillment of four human

Jewell provides the play-by-play. “They’re getting ready now,” he says. “They do a little shimmer, that’s it . . . They’ll repeat this many times.” The curator is wiry and very charged up about fish husbandry, a field in which he’s famous for his work with captive sharks. He has a grand-slam moment when our little fish get it on next to the side of the tank and a whitish speck appears and drifts downwarda fertilized egg.

“I can’t believe it,” he says. “You just got to see a Devils Hole pupfish egg! Let me tell you right now, that is a momentous occasion. Almost nobody gets to see that!”

Big grins all around. Cynthia seems especially pleasedwhich makes sense, because she’s one of the principals on a multi-agency team trying to ensure the continued existence of Cyprinodon diabolis. The pupfish, so named because they chase one another around like playful puppies, lives naturally in only one place, a bottomless pool in a bizarre fissure in the earth in a detached chip of Death Valley National Park in southwestern Nevada. The surface area of the pool is 318 square feetless than a standard room at Mandalay Baygiving plausibility to the claim that C. diabolis has the smallest habitat of any vertebrate in the world. It also occupies one of the worst fish habitats anywhere, with oxygen-poor water geothermally heated to 93 degrees, and a starvation diet based on algae and microorganisms. A trout would go belly up in minutes.

Rare and at risk to begin with, the species is inches from extinction, due to a mysterious population drop in the home habitat, made worse by an accidental massacre perpetrated two years ago by researchers. (More on that later. It’s so awful to recall that Cynthia tells the story in fragments, as if every word hurts.) Meanwhile, disasters have wiped out three artificial refuges designed to maintain reserve populations off-site. In September, when numbers usually peak, adult fish in Devils Hole numbered just 85well below the 400 biologists would be comfortable with. Figure in naturally low fertility, a life span of about 11 months, and a dearth of young surviving to adulthood and the picture looks troubling indeed for the fish and for those who care deeply about them, which seems to include everybody with any connection.

Because this isn’t just any cute, doomed species. It’s an ecological celebrity, a Save Me icon, and a frontline defender against developers who want to suck Nevada’s groundwater dry. The pupfish’s precarious situation has affected environmental policy and law, and the case for its preservation was actually heardand upheldby the U.S. Supreme Court. The National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife, and the state of Nevada, with private-sector support such as Shark Reef’s, have thrown themselves into the fight to save C. diabolis. As of this year, Death Valley National Park actually has a full-time fishery biologist on staff.

Besides, people simply fall for the fish. Cuteness sexed up by imminent peril does a number, even on me, a guy who previously couldn’t have cared less about weird little fish. “It’s a very endearing animal,” says Jewell. At another time and place, Cynthia shares a very un-federal-wildlife-biologist moment by telling me, “I do love them, I do. They’re so little, so blue, so happy . . .”

Ooh, girl, hold on to your heart. Your fish’s doom could already be sealed.

SHARK REEF’S THREE PUPFISH, the pair I see and a male bystander, are tanked in a small room off an immense nonpublic holding area used mainly for newly arrived creatures. To get here, I walked through Mandalay Bay’s casino and stopped to drink coffee at the foot of a huge, headless statue of Vladimir Lenincomplete with realistic pigeon shitthat proclaims the Russian-ness of Mandalay Bay’s Red Square restaurant.

Authenticity is the fantasy in the new Las Vegas; witness Shark Reef. Though Las Vegas itself may be an affront to conservation, and the mind rebels against the idea of a resort/casino/world-class public aquarium complex with official accreditation and peer respect and scientific props, Shark Reef is pretty much that. So far, management maintains a dignified silencenot a peep from PRabout its new, potentially species-saving emergency effort.

“We’ve laid extremely low, because our attachment to this has always been on the conservation side,” says Jewell, who adds, “We have no shortage of PRthis is Las Vegas, for God’s sake.” Jewell says the pupfish work is strictly pro bono. He declines to put a dollar value on the hours he and his staffers devote to the pupfish, because he hasn’t kept track. “Support from management is so strong, I’ve never even been queried on that,” he says.

Jewell says he started talking with pupfish people a few years back, with the idea of breeding Devils Hole pupfish both to help boost the population and to spotlight a Nevada fish in Shark Reef’s educational programs. A public exhibit was in the cards, too, but is now indefinitely on hold, because the situation is so dire. Jewell’s preparations to host C. diabolis began about a year and a half ago, when he brought in closely related Saratoga Springs pupfish. They’re thriving, with some on display in Shark Reef’s classroom for visiting schoolkids. Jewell has also had success with recently arrived accidental hybrids crossing the Devils Hole species and one of its closest kin, the Ash Meadows pupfish. (There are close to 40 species of pupfish in all.) Jack pulls an omigod face to express the hybrids’ hell-bent fecundity. After only a couple of months, Shark Reefhatched young are already trying to mate.

THE SUCCESS WITH OTHER PUPFISH shows how well aquarium propagation can work. All sorts of fish looking at the Big E have turned their luck around in just such a manner. So why not the Devils Hole pupfish? On the way out of Vegas, at the wheel of a dusty USFWS Jeep bound for Devils Hole, Cynthia tells me. “Guess what,” she says. “We don’t know how to reproduce them in aquaria.” Top fish people have tried and failed despite lots of promising fish sex; only one hatchling has reached adulthood.

I am fortunate in the federal ecocrat assigned me. Cynthia does her best to communicate in approved resource-manager fashion, but she repeatedly fails. She likes to tease and make gotcha jokes, with a cowgirl bounce and sass that hark to her native New Mexico. I ask her to lay odds on the pupfish’s survival. She asks sarcastically for clarificationsurvival in Devils Hole or elsewhere, with Devils Holelike fish bred back from the hybrids? Then, seriously, she says, “I still think we will be successful. Otherwise, I wouldn’t spend so much time on it.” The odds are, in her opinion, better than 50 percent.

In light of recent calamities, I’m guessing she means 50.0001 percent. In the late nineties, a decline was noted in the number of adult Devils Hole pupfish, counted in spring and fall by divers. Nobody panicked because, among other things, the fish were coming off all-time highs of nearly 600 in the previous few years. The presence of seemingly healthy pupfish populations in three operating refuges also gave comfort.

But in 2002, with counts in Devils Hole down to about a third of the mid-nineties’ highs, Fish and Wildlife, the National Park Service, and Nevada’s Department of Wildlife formed the Devils Hole Pupfish Recovery Team. Experts looked long and hard into the hole and saw a mystery that’s still unsolved. None of the usual suspects that do in native fishnonnative invaders, habitat degradation, pollutionhas been found in Devils Hole. The babies were simply not growing up.

To learn more, the recovery team approved a field study, which led to the worst thing that ever happened in Devils Hole: Pupfish 9/11. Really. On September 11, 2004, a storm caused runoff that washed a box of the researchers’ fish traps into Devils Hole. The traps sat unnoticed for four days.

Eighty adult fish perished in those traps, a third of all wild Devils Hole pupfish at the time.

By then, things had already gone south in two out of the three refugiaa fancy word for the roofed-over concrete pools that are the only places outside Devils Hole where the species has managed to multiply. A pump failure zotzed all the fish in the refuge at School Springs, in neighboring Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge. Around then, it became apparent that the fish in the nearby Point of Rocks refuge weren’t actually C. diabolis. Nobody knows how, but one or more wild Ash Meadows pupfish, C. nevadensis mionectes, got in and corrupted the population, creating the horndog hybrids currently making babies at Shark Reef. The last blow came this year with the shutdown of refuge number three, near Hoover Dam. It got slammed by a hyperinvasive nonnative snail that eats pupfish food. All three refuges remain fishless.

WE APPROACH DEVILS HOLE from the north, on a dirt road, skirting a smallish mountain clump that looks as if God accidentally overcooked it. Cynthia looks ahead and says, “There it is.” Her landmark is a tall chain-link fence surrounding an acre or so at the foot of the mountain.

After chilling in the Jeep’s air conditioning, the skin momentarily lies about the midsummer temperature, but here comes the truth: 110, unmitigated by the pizza-oven breeze. Devils Hole is, indeed, a hole. It brings to mind a flooded mine shaft.

To devotees, though, Devils Hole is a place for wonderment and deep thought. After staring silently for a second, Cynthia says she’s thinking about the hydraulics of the hole, a window on an ancient aquifer. Elsewhere the water is trapped thousands of feet down, but here it follows a fault upward. The collapse of a cavern roof about 60,000 years ago opened up the hole, whose depth is unknown. So far, divers have gone down 460 feet without finding the bottom. Theories vary about when and how fish got in, but there’s general agreement that it happened roughly 10,000 years ago, at a time when this part of the world was still wet. Some scientists entertain a theory that genetic exhaustioncousins marrying cousins for millenniacould be the real species killer here.

Cynthia also muses about one of the hole’s spookier phenomena: sloshing brought on by distant earthquakes. During an earlier visit I made to Devils Hole, Death Valley park biologist Linda Manning told me that the 2002 magnitude-7.9 Denali earthquake, in Alaska, caused the hole’s water level to rise and fall about six feet. Lunar gravitation also moves the water higher and lower with the same twice-a-day rhythms as ocean tides. Manning let me go down to the water’s edge, where three inches of wetness marked a drop from high tide to low.

The most practical down-hole path leads to the edge of a shallow shelf, about 17 feet long and six feet wide, with balls of fuzzy algae and a few packs of fish chasing around. Though they swim down to 80 feet or so, pupfish pass most of their time up on the shelfhatching, growing, spawning, feasting. No shelf, no pupfish, the savants say. And the margin of survival, in terms of water level, is small. Mike Bower, Death Valley’s fishery biologist, says a drop of six inches would be big trouble and adds, “A foot could be the coup de grace.”

C. DIABOLIS ORIGINALLY CAUGHT my interest because a weird little desert fish having a Vegas honeymoon at Mandalay Bay, watched over by government wildlife nerds, sounded like a scream. But then I went to Nevada and quit laughing. The Devils Hole pupfish matters.

It is, among other things, one of the founding endangered species, recognized and protected long before endangerment was an official status. In 1952, President Harry Truman proclaimed Devils Hole to be a detached part of Death Valley National Monument (now National Park), in order to preserve the hole’s unique features, especially the fish.

In the late sixties, an agricultural developer sunk wells next to Devils Hole. The water level dropped alarmingly, to the point of baring parts of the spawning shelf. Thus began 15 years of court fights and public pissing matchesfeds and enviros versus pro-development, anti-government Nevadans. A local county commissioner printed up KILL THE PUPFISH bumper stickers, and a newspaper in Elko called for some bold individual to clear up the problem by dropping poison into Devils Hole.

Just in time to save the pupfish, the feds got a court order to shut down the wells that were lowering the water level, which subsequently rebounded enough to cover the spawning shelf. Higher courts slapped down challenges all the way up to a landmark pro-federal, pro-pupfish ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1976. The courts actually mandated a minimum water level in Devils Hole.

In 1980, another developer bought up land around Devils Hole. But once again the government intervened, and the company eventually sold its land to the Nature Conservancy, which in 1984 sold to Fish and Wildlife. The agency then established the Ash Meadows NWR, a miracle of wetness and green watered by 33 seeps and springs. Thanks to time and rehab efforts, Ash Meadows is slowly reverting to a facsimile of the paradise it was. And 27 species of plants and animals that are found only in the immediate area, a dozen of which are listed as endangered or threatened, have a home in perpetuity. For this triumph of conservation we can thank our unlikely hero, an inch-long fish.

One shudders to think what might happen without pupfish residing in Devils Hole. As one agency official says, on condition of anonymity, “Lose the fish and you lose it all.” The “all” refers to a vast aquifer underneath the desert. Terry Fisk, a hydrologist for the National Park Service, says that, in the absence of pupfish, today’s court-ordered water level would become negotiable. Lowering it could imperil Ash Meadows or jeopardize springs and endemic critters and plants down in Death Valley. So the Devils Hole pupfish is more than a relicit’s the future.

Fisk speaks the truest words I hear on the fate of the pupfish. “The poor little bastards don’t have much going for them, do they?” he says. “But they’re survivors. At least so far.”