SO THERE WE WERE, on the north shore of the Noosa River, not far from where it empties into the Pacific Ocean, a little less than two hours north of Brisbane. Our guide and example in all things on this equestrian holiday, three-time Olympic pentathlete Alex Watson, had decided to try us out (no doubt assessing our skills, though he was too polite to say so) with a beach ride—by trail from the Noosa North Shore Resort and then onto the sand. When I looked left as I came out of the woods, I could see what appeared to be 30 miles of flat, sunny, golden, wet, surfy shore, a sand highway fringed by blue water and dotted here and there with surfcasters. It was only the most welcoming beach I had ever seen, but all in a day’s work for Alex. We turned right and rode down toward the water, then we trotted and galloped in the surf, which was exhilarating, as long as you didn’t look down at the waves swirling around your horse’s feet. “Oh,” said one of the two girls helping Alex, “we had the pony out here the other day, and he kept looking down until finally he lost his balance and fell over.” I could sympathize. One look down and I was rocking back and forth.

horseback queensland

JUMP START: A kangaroo at home in Queensland

JUMP START: A kangaroo at home in Queenslandhorseback queensland

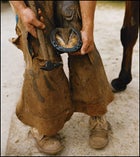

NAILING IT: Shoeing a horse in the Noosa hinterlands

NAILING IT: Shoeing a horse in the Noosa hinterlandshorseback queensland

COOL CROSSING: Riding through Queensland’s Booloumba Creek

COOL CROSSING: Riding through Queensland’s Booloumba CreekBut Simon, my mount, was an experienced beach galloper, and he never looked down or stumbled in any way. He just kept galloping toward what we discovered to be a picnic tent set up just for us, including some South Australia chardonnay and a local delicacy, “Moreton Bay bug meat,” a Brisbane version of lobster. We cooled the horses off in the water, then enjoyed a two-hour lunch. Afterwards we rode it off as we made our way back to the resort. It was luxurious and exotic and satisfying, especially considering that it was only the trial ride and the best was yet to come.

I had already identified Alex, 47, as a bona fide character. Olympic pentathlon involves five high-energy sports—swimming, running, show jumping, fencing, and shooting—but Alex, who grew up in Sydney, also surfs, plays tennis, eats heartily, and conducts lots of business on his cell phone. In addition to being blond and lean, which you would expect of an athlete, he is talkative and funny (which I suppose you would expect of an Aussie), but he is never, ever tense. “Equable” is how his wife, Karyn, puts it.

Alex’s mount was Xena (the Warrior Princess), an aptly named graceful black mare who never walked when she could trot and never trotted when she could canter or gallop. Simon, a sturdy chestnut Australian stock horse, some six years old and of medium height, had spent his youth mustering cattle, and he had that cow-horse air of suave imperturbability. My friend Christine Jeffs, who had come over from New Zealand to meet us, was on Soloman, also allegedly a stock horse, but taller and more slender, more of a Thoroughbred type. In 2004, Alex had taken over the equestrian facility of the Noosa North Shore Resort, a nicely situated but old-fashioned facility that was being modernized for ecotourism. His job was to develop a set of rides that would use the resort as a base, taking advantage of 103 miles of newly opened equestrian trails in the Noosa area, which we, on a trip run by Cross Country International, a U.S.-based outfitter, were to see over the next few days.

The town of Noosa Heads is famous for beaches that simply go on and on, and has become, in the past few years, a bustling resort area. In July and August, the air temperature is in the seventies, and the water temperature is about the same. Surfers abound. Noosa is also famous for the Glass House Mountains, a row of exotic-looking lava plugs whose volcanic cones have eroded away, leaving more or less steep and forbidding igneous prominences, the subject of Aboriginal tales and beliefs.

THAT NIGHT WE HAD DINNER at a nice bistro (called Bistro Bistro) in Cooran, just down the street from Gelignite Jack’s “Dynamite Discounters” (where I had thought, for about five minutes, that they were really selling dynamite). We talked, as Aussies and visitors so often do, about crocodiles, snakes, sharks, and funnel-web spiders. “Twenty minutes,” Alex kept saying, “that’s all you would have.” And though he was laughing and putting me on, I knew it was probably true: That was all I would have.

The next morning we woke up in the interior at the Noosa Avalon Cottages, looking through a picturesque mist at Mount Pinbarren. Our plan was to drive from location to location for trail riding, always stopping at a restaurant along the way. Today we were to try one small trail leaving from Cooran in the morning, and then another, longer trail in the Black Snake Range in the afternoon, but the horse van had clutch trouble. We sat waiting in Cooran’s post office/caf茅, reading a thick publication called Horse Deals, an Aussie horse and horse-equipment magazine just as thick as the fall fashion issue of Vogue. Christine and I leafed through to see what might be on offer. Christine, I should say, was already in love with Soloman and was envisioning just how he would work out if she shipped him back to New Zealand and put him in training as a three-day-event horse with her others.

I had no such fantasies about Simon, the U.S. being much too far away, but of course I was encouraging her. Alex said we were bona fide “horse tragics,” but so was he. Only two weeks before, in response to an ad, he had driven a thousand miles and back to pick up a kindly chestnut mare intended for Karyn. He’d had to go on the spur of the moment, since nice horses frequently sell within a few days. Horse Deals is merely a symptom of the general Aussie passion for horses. The country’s biggest horse race, for example—the Melbourne Cup, in November—is of far greater national import than the Kentucky Derby or Britain’s Epsom Derby.

Karyn and her mare joined us for the afternoon ride in the Black Snake Range, near the town of Kilkivan. Kilkivan is maybe 50 miles from Noosa, but it looks like a prairie town in western Iowa—flat, fertile, open, and agricultural. It’s the home, every April, of another Aussie equestrian event, the Great Horse Ride, in which a thousand horses converge on the town and parade down the main street to a festival at the show grounds. Alex, who’d participated in the most recent ride, said it was really quite amazing to see a thousand horses all in one place. “It’s intimidating for some of the horses,” he said. “They get a little excited.” Not Simon, I thought, and my instincts were confirmed an hour later, when we were tacking up and 40 or 50 or a hundred cows, pale-gray Brahmans or Brahman/Charolais crosses, appeared like a wave at the end of the road, galloping in our direction. Horns. I bent down and peered toward them. Bulls. At least one or two. I hid behind the truck. Simon perked up. But the cattle, seemingly on their own, decided not to pass us, or, rather, to inundate us, but to turn back the way they had come.

On the Black Snake trail, there were eucalyptus trees everywhere, but also a couple of famous trees, called bunya pines, that drop cones every three years, something that used to be the occasion for celebrations by Aboriginal peoples. From one promontory, we could look into three different valleys.

Simon and I were better acquainted now. He conformed to the theory that every horse has certain speeds in every gait that make for the most efficient use of energy. For whatever reasons of stride length or build, Simon’s preferred speeds were slow, and usually we found ourselves watching the haunches of the other horses as they disappeared into the distance. To make up for this, Simon liked to trot after them, employing his most efficient trot, which was faster than a walk but not what you would call brisk. For a while I considered it my job to do with Simon what I would do with my own horses, which was to make him walk faster. He was agreeable to that in a way, but we both eventually decided, Why bother? He was a dedicated hill climber, though, and on every steep slope was at or near the front.

AT NARGOON, where we were met by ranchers and cattle breeders Bob and Sheree McGill, I asked the obvious question: “Is 6,000 acres as far as the eye can see?” Bob’s answer, allowing for his modesty and for the details of acquisitions and sales over the years, was yes. But Nargoon’s greatest luxury wasn’t mere space. Yes, we ambled along for a considerable period of time, looking for cows and chatting. Yes, I admired the landscape, which was dry and gently rolling. It reminded me of one of my favorite landscapes, that of the ranch country around Paso Robles, California. And, yes, once we found the cows, it was fun to muster them, meaning to round them up. Our only challenge, once we found them lounging by a pond about an hour’s ride toward the back of the ranch, was to get the entire group of 40 through a smallish gate in a long fence, and in order to turn some of the strays, Alex and Christine got to gallop, yelling, across the broad hillside in the best giddyup tradition.

After the cows went through, Bob asked us if we wanted to take a gallop, and my heart went into my throat. All the way out and all the way back, I was eagle-eyed for holes, because in California every field is pockmarked with horse-killing gopher, ground squirrel, and badger holes. But no. They knew nothing about holes at Nargoon. Maybe a rabbit hole? They shrugged, and I thought, 6,000 acres without holes! A miracle!

As a cattle pusher, Simon was even more inspired than he was as a hill climber. He walked along with fervor, sometimes having to be held back. “Oh,” said Alex, after we had put the cows into their new pen, “look at him. He’s despondent.” True. Simon’s head hung low. Back to the uninspiring work of trail riding. We turned onto a path that led into a small wood and rode for another half-hour. Then, lo and behold, we found Bruce Hurley—our hotelier from the Left Bank, in Kilkivan, where we had stayed the previous night—who had prepared us a barbecue. As we were riding out an hour later, we met up with Lyndon Davis, an Aboriginal musician from the local Gubbi Gubbi tribe, who spread his instruments and artifacts on a blanket in front of a huge eucalyptus tree. He told us some local history, played two beautiful didgeridoos, and showed us how to throw a boomerang. When he threw it, it went out in a high circle, spinning flat above the trees, and on the return reached a point above our heads where it pivoted, slowed, and spiraled into the grass. When we threw it, it went out and we went out after it, looking for it.

Cattle mustering made for a long day, and we didn’t arrive at our lodging for the night, the Bellbird Lifestyle Retreat, near the Booloumba Creek area of Kenilworth State Forest, until after dark. When we got there, I was intent upon taking a hot bath, sitting in the sauna, and turning into a puddle of relaxation. I discovered the best thing about the Bellbird Lifestyle Retreat in the morning, though, when I woke up and opened the curtains. Before my gaze was a misty, lush forest, falling away in steep slopes and verdant levels to a hidden valley below. The morning sun was lighting up the mist, and the magical scene was accompanied by a chorus of birdsong—bellbirds, pied butcherbirds, cockatoos, and countless others, unlike anything I have ever heard, so rich and musical that I made a recording with my digital camera out of sheer astonishment. And only 20 miles or so from Nargoon, only 40 miles or so from Noosa.

OUR PLAN for the Booloumba Creek trails was to ride about 16 miles through the state forest (922 square miles of subtropical rainforest) with Brook and Leigh Ann Sample, breeders of endurance horses (usually Arabians, who race as much as a hundred miles over varying terrain) and managers of the sheik of Dubai’s endurance-horse operation. I was sorry to leave Simon behind, especially when I saw my mount for the day, Arch, who was short, thin, and not particularly pretty. But safe, evidently safe. The Samples were friendly and responsible, but there was, of course, occasion for that croc-snake-spider thing. Every time we passed a certain plant, Brook called out, “Gympie stingers!” We were not to touch the broad-leafed gympie stingers. I didn’t know what their effect would be, but I was sure whatever it was would be painful and take 20 minutes or less.

After a while, Brook revealed Arch’s registered name, La Mancha Archduke, and I decided that I wasn’t the only one who had noticed a resemblance to a certain famous literary mount, Rocinante. But no. In the course of our three-hour ride, often at a fast trot or a gallop, through the forest trails and up at least one long, treacherous slope (at a gallop) that was steeper than any slope I had ever ridden, Arch revealed his true nature. “Oh, yes,” said Leigh Ann, “just two weeks ago he won a 50K race.” Arch was polite with me but firm. As the ride progressed, he got farther and farther out in front, deigning to trot if I made him (and his trot was big) but preferring to gallop, and always sure, whatever the footing. At one point, Christine, on an almost equally determined mare, was the only one still with me. After a long gallop, Arch slowed down to a trot, and I said, “At last he needs a rest”—but only for three strides. A moment later Arch was galloping again, tireless and ever eager. Our index was Xena, who normally couldn’t be induced to walk. When Xena was heaving, La Mancha Archduke was hardly drawing a breath. Brook told me he expected Arch to place in the top three in a 100-mile race at the Australian national championships this year. A day on him was arduous but thrilling.

Christine returned to New Zealand before our last day, which was to be a quiet one—a last ride, from the Noosa North Shore Resort, only Alex on Xena and me back on Simon, in the surf of the North Shore’s Teewah Beach—but who should turn up other than Guy McLean, horseman extraordinaire, with his three bright grulla youngsters (dun horses with a pronounced dorsal stripe and zebralike stripes on their legs). Guy, who is 30, is a horses-horses-horses-all-the-time sort of fellow, an example of a certain type of Australian horseman whose expertise is rooted in stock-horse training but who has taken it to a very high level, giving popular exhibitions in Australia as well as the U.S.

Guy’s horses do several astonishing things, all at liberty, without saddles or bridles. They gallop and turn in a small portable ring he brings. The best thing he showed us was when he asked one of his three horses to lie down like a dog, his hooves curled beneath him and his chin tucked, and then asked the other two horses, together, to sidestep over the down horse, until he was boxed between their eight legs. Then Guy stood on the rumps of the two horses and cracked two bullwhips in the air. The horses’ reaction to all this was on the order of a yawn—no big deal. Then the standing horses sidestepped from the down horse, the down horse stood up, and everyone got a pat. After we marveled at Guy, who has been training horses since he was 15, Alex and I agreed that he was the truest horse tragic of all.