“The question is not if but when we’ll be drowned,” says Paani Laupepa, Tuvalu’s point man on climate change.

“The question is not if but when we’ll be drowned,” says Paani Laupepa, Tuvalu’s point man on climate change. A thin strip of Funafuti Atoll snakes its way across the Pacific.

A thin strip of Funafuti Atoll snakes its way across the Pacific. Pastor Molikao Kaua worries about the flood next time.

Pastor Molikao Kaua worries about the flood next time. Chief Finiki and his no-good pulaka plants.

Chief Finiki and his no-good pulaka plants. One of the many trash pits on the island.

One of the many trash pits on the island. Two Tuvaluans munch raw fish heads as the sun goes down on Funafti’s lagoon.

Two Tuvaluans munch raw fish heads as the sun goes down on Funafti’s lagoon. Siligama Taupale, who drifted for five months at sea before being rescued.

Siligama Taupale, who drifted for five months at sea before being rescued. Adieu, Fongafale.

Adieu, Fongafale.

IF YOU HAVEN’T HEARD of Tuvalu, the fourth-smallest country in the world, so much the better, because its nine square miles of dry land may soon disappear from sight like a polished stone dropped in the deep sea. And if that happens, it might be unpleasant to consider that the basic amenities of our lifestyle-our cars and planes and power plants, our well-lighted, well-cooled and -heated homes-have brought about the obliteration of an ancient, peaceful civilization halfway around the world.

I’m getting sunburned. The equatorial heat is scorching, and the conversation of my host-a sneaker-clad 29-year-old conservation officer named Semese Alefaio, who prefers to be called Sam-is inclining toward doomsday. Sam is piloting our skiff into a vast lagoon encircled by the 24 wisps of land that make up Funafuti Atoll. Funafuti is the capital of Tuvalu, a chain of nine islands-six coral atolls and three limestone reefs-scattered across 350,000 square miles of otherwise vacant South Pacific blue. Scads of silvery fish leap above the water’s punishingly bright surface; not far away, a dolphin crests, hangs suspended above a wave, and vanishes.

“This is heaven, yes?” Sam remarks. He speaks in a flat, affectless voice, staring straight ahead as he steers. With long, thick hair pulled back in a ponytail, Sam looks like a Calvin Klein model. But jeans are not what he’s advertising.

“There,” he says, gesturing above the waves with his chin, “that’s the sinking island.” All I can see are waves converging in skittish little folds as we approach a reef.

“Which sinking island?”

Sam tries not to show his impatience. After all, I’m a palagi, an outsider, and Tuvaluan courtesy dictates polite forbearance of my cluelessness. Sam knows that I’ve come here to bring back ghastly news from global warming’s paradisiacal ground zero, since Tuvalu is the first sovereign nation to announce it is being swallowed by the planet.

“Look to your right,” he instructs. “You see now?” I begin to make out a spit of land-a dozen coconut palms clinging above a sidewalk’s width of beach. “Those trees are beginning to fall down from erosion,” he tells me. “That’s what the sinking island looked like a few years ago.” He pauses and looks at me. “Now,” he says, “look straight ahead.”

A barren rocky outcrop comes into view above the waves. “Tepuka Savilivili,” Sam says, naming what’s left of the island. He anchors the boat and I wade toward the rocks. The water temperature, at 84 degrees, is catching up with the air temperature. A recent tide line darkens most of Tepuka Savilivili’s oval remains, which are barely 200 feet long and 50 feet across. I climb ashore, and a fluorescent green crab clatters past me. A tern circles above. Sam tells me he remembers when there was a sandy beach here. Now there’s nothing but black, jagged coral that looks like decoration for a lunar stage set. A shallow, bleached pit in the center marks the spot where a cluster of trees once took root. In 1997, Sam says, Cyclones Gavin, Hina, and Keli blew across the lagoon; the trees were uprooted by wind and waves, and soon afterward the island began to wash away. Where Tepuka Savilivili’s miniature forest once stood, I find some plastic bottles, a container of laundry detergent, and a trio of desiccated coconuts. Waves batter the rock from all sides.

“Tepuka Savilivili is just a sign,” Sam says, “but the signs are everywhere.” The seas, it seems, are heating up, and therefore rising, and Tuvalu’s leaders have warned their population of fishermen and farmers and merchant seamen to brace for a contagion of shrinking and sinking. Other islets in Funafuti’s lagoon have lost up to 80 percent of their land in recent years.

Sam and I climb back into the boat. “People used to come to these little islets if they had a problem,” he tells me. “They’d come here for the day. It’s quiet, it’s natural, they forget their problem and go home with a clear mind.” We approach the dock at Fongafale Islet, Funafuti’s overcrowded, semi-bustling, haphazardly beautiful hub, home to nearly half of the country’s 11,000 citizens. “Now people are trying to leave Tuvalu,” Sam says. “They’re afraid for their lives.”

WHAT DOES A COUNTRY DO when it knows it is of no concern to the rest of the world, has no natural resources to sell, occupies a location so exposed to the elements that it seems geography has played a bitter joke, and emerges from colonial dependency into the warming-up postmodern world?

It does what it can to survive for all the dwindling days that the earth has allotted it.

For the last decade, environmentalists have been eager to christen Tuvalu the proverbial canary in global warming’s coal mine. Jeremy Leggett, who was scientific director of Greenpeace’s Climate Campaign in the 1990s, told me that Tuvalu “is a microcosm of the horrors that await us if blindness and idiocy like that of the present American government continue. Tuvaluans are the first victims.”

Of course, were it not for the reports of its impending demise, few people outside Tuvalu would know that it existed at all. Put together, the nine islands cover less ground than Manhattan, and their highest point is 16 feet above the sea. The nearest movie theater is in Fiji, roughly 600 miles to the south. Under British rule until 1978, Tuvalu didn’t even rate its own colony; instead, the British yoked Polynesian Tuvalu to its Micronesian neighbor Kiribati, calling the package the Gilbert and Ellice Islands. (Tuvalu was Ellice.) Despite its current value to environmentalists, none I spoke with had visited the country or could even pronounce its name properly (accent on the second syllable: Tu-VAH-lu).

Tuvalu, though, has slipped comfortably into its role as environmental cause c茅l猫bre. A succession of prime ministers have captivated the press at international gatherings like the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992 and, more recently, this summer’s World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg. Tuvalu anted up to join the United Nations in 2000, hoping, according to Ambassador Enele Sopoaga, “to draw attention to the adverse effects of climate change and sea-level rise on the survival and livelihood of Tuvalu’s people.” In March, at a summit of Commonwealth nations held in Coolum, Australia, Prime Minister Koloa Talake predicted that his homeland would be gone within 50 years, and appealed to the leaders of Australia and New Zealand to guarantee Tuvalu’s population a dry migratory destination.

“Flooding is very common. When it is high tide, the flow has gone right into the middle of the island, destroying food crops,” Talake told a news conference in Coolum. “Islets that used to be my playing ground when I was ten or eleven years old have disappeared, vanished. Where are they? . . . These things were there and now they have gone; somebody has taken them, and global warming is the culprit.”

Talake got a cool response from his biggest South Pacific neighbor. The Australian government-which asserts that “the likely impact of climate-change-induced sea-level rises in the Pacific is not immediate”-flatly rebuffed Tuvalu’s calls for immigration. New Zealand, on the other hand, amended an existing temporary-employment program to allow 75 Tuvaluans a year to apply for residence.

At the same summit, Talake raised the prospect of filing suit in the International Court of Justice against the United States and Australia for their prominent role in pumping up the atmospheric greenhouse with carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases. Groups like the New York-based Natural Resources Defense Council, which continues to investigate the strategy of mounting anti-tobacco-style litigation against big global warmers, are aware that Tuvalu could make an agreeably desolate plaintiff. “If I lived in Tuvalu,” Jon Coifman, the spokesman at NRDC’s Climate Center in Washington, D.C., told me, “I’d be concerned with basic justice and with reparations for the fact that my country is about to go underwater.”

IT TURNS OUT THAT JUSTICE and reparations are precisely what Tuvalu is concerned with, though perhaps not in that order. Paani K. Laupepa, a vigorous and articulate 40-year-old assistant secretary in the Ministry of Environment, Energy, and Tourism, is Tuvalu’s point man on climate change. The day I arrived, he greeted me at Funafuti’s airstrip wearing a business shirt, flip-flops, and a skirtlike garment called a sulu, and immediately inquired after the carton of cigarettes, two bottles of liquor, and package of chocolates that he’d asked me to bring him. He expressed his hopes that I would prove useful in his government’s “public relations campaign.” Then he fell silent, and gave me a stern once-over. “What are your motives?” he asked.

Let’s be honest: I’d come in search of imminent catastrophe. But it seemed like a strange question, and instead it made me think: Paani Laupepa, what are your motives? Why has Tuvalu, alone among the world’s five atoll nations and its many low-lying island and coastal countries, embraced the cause of global warming with such single-minded urgency? The Marshall Islands and Kiribati and the Maldives-pancake-flat island chains all-are also prime candidates for erasure, but the world has yet to be serenaded by repeated bulletins heralding their death throes. I had a flash of panic: Tuvalu is sinking, isn’t it?

“My motive,” I told him, “is to learn as much as possible about the impact of global warming on Tuvalu.”

“Relax,” Laupepa said. “Take a swim. You’re in the islands now.”

I wasn’t the only palagi who had beaten a path to Tuvalu’s officially sanctioned farewell tour. During my week on Funafuti, the members of what we jokingly referred to as the Tuvalu Press Corps included an Australian documentary filmmaker who told me he’d wept upon reading Tuvalu’s report to a UN agency on climate change; an earnest American writer-photographer couple whose identification with the natives extended to wearing Tuvaluan garb and spending a night sleeping alongside islanders on mats on Funafuti’s airstrip, which does quadruple duty as runway, playing field, gathering place, and frequent nighttime crash pad for locals; and a Finnish writer who had journeyed there by ship, because she refused to contribute to global warming by flying.

Each of us, I’m certain, was intent on bringing home some version of the poignant and alarming story that had begun to appear in the world’s press. The Japan Times, August 2001: “Their burial grounds, their schools, their homes, their churches will be enveloped by the ocean. The Tuvaluans can never go home again.” The Los Angeles Times, February 2002: Tuvalu “may comprise the first country to pay the ultimate price for a changing climate: national extinction.” The Guardian of London, that same month: “The evacuation and shutting down of a nation has begun.”

It’s irresistible-the stuff of disaster movies and Atlantis myth, perfectly suited to plucking the heartstrings of well-intentioned foreigners-and Tuvaluan officials are only too happy to oblige with print-worthy quotes. “The question,” Laupepa told me, “is not if but when disaster strikes, and not if but when we’ll be drowned.”

Still, I couldn’t avoid detecting, from the moment I arrived, an uncomfortably opportunistic strain in my government hosts’ entreaties. That week, Tuvaluans would be voting on a new national government. Fifteen members of parliament would be elected; since there are no political parties, each of those 15 had his sights set on building a majority coalition and becoming the next prime minister. Koloa Talake had brought attention to Tuvalu’s plight on the world stage, but his four years were up, and some of his critics at home considered him aloof and ineffectual. He faced strong opposition from the likes of former prime minister Kamuta Latasi, an old-timer who opposed dabbling in global affairs and regarded the idea of a lawsuit as a pipe dream.

Prime Minister Talake, however, was bracingly frank about the value to Tuvalu of playing the annihilation-by-global-warming card. He stunned one of my colleagues in the Tuvalu Press Corps by stressing, again and again, that the expense of mounting a legal challenge to the United States and Australia could be justified on practical grounds. “You’ve got to spend money to make money,” he declared.

In short order, then, I came closer to understanding at least one dimension of Paani Laupepa’s motives in regard to the press, generally, and to me, in particular. “You might come in handy,” Tuvalu’s designated enviro-flack told me one morning. “How rich are the readers of your magazine? Very rich? We want to reach the super-rich. Put my name and e-mail in your article in case some of your readers are interested in helping us. If this publicity leads to sympathy and assistance, that’s the fallout-the collateral advantage. We’ll take it.”

Tuvalu may have been sinking, but not as fast as my hopes for a tidy glimpse at the perils of global warming.

BEFORE I LEFT TUVALU, I had ample time to convince myself that global warming is the mother of all scenarios of environmental-and social, and economic-collapse. This is not propaganda: Global temperatures went up by about a degree during the 20th century; in April, an article in the journal Nature suggested that temperatures are likely to rise another 2.3 degrees in the next 20 to 30 years. The largest and most authoritative international body of experts in such matters, the 2,500-member Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), operating under a joint mandate from the UN and the World Meteorological Organization, has warned that the planet might warm up by as much as 10.8 degrees over the course of the 21st century.

Although the warming and its effects are global, Americans, representing 4.6 percent of the world’s population, have plied the atmosphere with about 29 percent of all insulating greenhouse gases emitted by human activity over the last century. Chief among them is carbon dioxide, exhaled in great gasps by every car and every furnace and every power plant. Nonetheless, in March 2001, President Bush renounced his predecessor’s signature to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol on Climate Change, calling the treaty “fatally flawed” and inimical to American economic interests. He refused to commit to reductions in greenhouse-gas spewing so modest that most observers considered them merely a symbolic first step.

“Sea-level rise will cause major disruptions,” says Robert T. Watson, chief scientist at the World Bank, who was chair of the IPCC for six years, until the Bush administration, prodded by its friends at ExxonMobil, lobbied vigorously to remove him from the post this year. (He was replaced by Rajendra Pachauri, an engineer from greenhouse-gas-friendly India.) “I believe that the very large majority of scientists-95 percent would be a good number-agree with IPCC findings,” Watson told me.

The IPCC’s weather forecasts, as laid out in its 2001 Assessment Report, make the Dark Ages look like a Tuvaluan beach party. Droughts will afflict much of the world, with especially nasty thirst in store for the 1.3 billion people, including Tuvaluans, who currently lack adequate access to clean water. On the other hand, the quarter of the world’s population that lives in the great river valleys of Asia is apt to find itself treading the waters of deluge due to the rapid retreat of the Himalayan glaciers. Warmer climes will abet the spread of malaria-bearing mosquitoes, and of agricultural pests, and of hungry critters like the beetles that have hollowed out 38 million spruce trees in the past few years in Alaska’s Chugach National Forest. Even marginally warmer seas will bleach, and then kill, coral reefs, which sustain the greater part of marine biodiversity.

As in all things, poor parts of the world will cope especially poorly with the changing climate, while the temperate latitudes of the United States will fare more hardily. But that doesn’t mean that North America is in the clear. Geoff Jenkins, a climate modeler at the British Meteorological Office, one of the world’s leading centers of climate research, says that, on top of the four to eight inches that the world’s seas rose during the 20th century, the water, which heats up much more slowly than land, would be saving its best for the foreseeable future and beyond.

“The average projection for the next hundred years is something like half a meter’s rise,” he told me, though the high end of the estimates verge toward twice that. Even more ominous, the gathering flood will be compounded by its own unstoppable inertia. “Once it gets started,” Jenkins added, “no matter what you do about emissions, the ocean almost doesn’t notice. The sea level continues rising for many centuries afterwards.”

How that affects our weather patterns is tricky. Scientists have only recently begun to discover how abruptly the earth’s climate has shifted in the past from hothouse to ice age-which is to say, nature has a fickle mind of its own. But figuring in the last two centuries of fossil-fuel burning, the current forecast is grim: Higher and hotter seas will bear more frequent and savage storms, accompanied by torrential flooding, like the kind that turned Prague into a Kafkaesque water park this summer. New Orleans and New York will have to undertake massive public-works projects to stay dry; Rotterdam and Venice will be lucky to make it. And perpetually forlorn Bangladesh is in for more good times, with 17.5 percent of its land-home to 17 million people and locus of half its food production-in danger of being engulfed.

“You could have a major dislocation in almost all low-lying deltaic areas, whether it be in Bangladesh, or Egypt, or the Pearl River Valley in China,” Robert Watson told me. “One could conceivably see tens of millions of people being displaced, leading, potentially, to a large number of environmental refugees in areas where there are already regional conflicts.”

And Tuvalu? At an average altitude of six feet above sea level, Tuvalu is apt to be stargazing from the wrong side of the water long before the oceans rise almost two feet. “We are endangered,” said Ambassador Sopoaga. “And you know, endangered people can act in desperate ways.”

I WANT TO TALK to the endangered people. It shouldn’t be hard to do. Even on a good day, Fongafale Islet feels as secure as a precipice. It snakes in a graceful north-south arc for about seven miles, and ranges from 20 feet wide at its narrowest point to about 400 yards at its plumpest. As Paani Laupepa muses during one of our conversations, Fongafale’s highest ground is the upper level of the guest house where I’m staying-about a dozen feet above sea level.

I start out on foot on Fongafale’s eastern side, where a 15-foot surf is breaking close enough to shore that I can reach the waves with a good fling of a rock. A few footsteps inland is a tidy whitewashed structure with yellow window frames, housing Tuvalu’s Department of Meteorology. On a wall opposite the entrance to the building is a framed photograph bearing the caption high tides 9 FEBRUARY 2001. The photo shows the staff of six standing in calf-deep water outside the office.

About a quarter-mile away, across the airstrip from the meteorological office, I meet up with Siaosi Finiki, the chief of Funafuti-a largely ceremonial position, but one that carries great respect among the islanders. Finiki, 68, is barefoot and wears a bright orange sulu, an orange tropical shirt, and a straw hat. For ten generations his family has survived by fishing and planting crops on Funafuti, a practice that he believes he will be among the last to perform. He shows me what is left of his croplands-a plot, perhaps 25 feet square, grown thick with stalks of pulaka, a starchy root vegetable that is one of Tuvalu’s historic staple foods.

“Look at this plant,” he says dejectedly, running his finger on the yellowed edge of a leaf. “It’s limp. It’s no good.” He dips a finger into the water that runs in a shallow drainage channel. “Salty,” he says. “Taste it.” I sprinkle a little brackish water on my tongue. Seawater, Finiki says, has infiltrated the layer of fresh water that sustained his plants. When did it start? “Maybe five years ago,” he says, referring to the same storm that swamped Tepuka Savilivili, in Funafuti’s lagoon. “A big wave came ashore and covered the land. Since then, people aren’t planting so much. The fruit is smaller and doesn’t taste good. Sometimes it’s rotten.”

Finiki glances around at the untended gardens. “Life has changed so quickly,” he says matter-of-factly, “because of how Westerners have oppressed us. When I was young, we lived on fish, pulaka, coconuts, breadfruit. Now everything is money, money, money. I’m the only one in my family who still eats pulaka. I urged my children to try it, but they don’t like it. They like imported foods that take no time to cook, like tinned corned beef. That’s OK, because the crop is no good anymore.” We turn and walk back to the road, where the chief’s single-gear bicycle is leaning in a ditch. “I’ll plant as long as I live,” he says. “The crop is no good, but I’ll keep planting.”

Four miles away is the northernmost house on the island, a cinder-block compound occupied by Bikenibeu Paeniu, Tuvalu’s current finance minister and a three-time former prime minister. In 1989, Paeniu became the first of Tuvalu’s leaders to press ardently for international recognition of Tuvalu’s vulnerability to global warming, and he was for a time a darling of the environmental movement. In 1993, he toured the United States and Japan with Greenpeace, delivering pleas concerning “genocide by environmental destruction,” and received an indelicate snub in his attempts to gain a five-minute audience in the White House with the environmental champions Clinton and Gore. Now 46, of squarish build and weary as an old boxer, Paeniu affects a philosophical approach to his country’s seeming insignificance.

“It’s really sad, the American stance on Kyoto,” he tells me. “I think the global powers know in their hearts and beings that climate change is taking place, but it’s simply not the priority for them that it is for us.”

We sit in the yard beside his house, shaded by fruit trees. Discarded car parts lie near a clothesline. A few women sit on a raised platform, weaving palm leaves into a mat. The ocean is so close I can feel a salty glaze on my skin.

“Listen to that wind,” he says, as the leaves rustle above us. “This is supposed to be the calm time of the year. Now, everything happens randomly. Cyclones come in the dry season, and instead of once every few years, they come two, three times a year. It’s quite unusual. To others, climate change is just a political dispute, but we are experiencing its effects firsthand, and we lack the resources to contend with it.” He kicks the ground with a bare foot. “We have the God-given right to this land,” he says. “If we are forced to move somewhere else, we are nothing but aliens.”

TWILIGHT. The sky over Funafuti’s lagoon is a rich smear of reds and golds worthy of a Turner seascape. At sunup and sundown, the lagoon becomes a communal meeting place for locals. I’m swimming in glimmering chest-deep water 50 feet from the offices of Tuvalu’s policymakers. A couple of men troll the water with nets. I nod a greeting toward a woman who is discreetly soaping herself beneath the water’s surface, then slosh over to a circle of three others who stand gossiping and eating raw fish heads and coconut from a floating zinc bucket. They offer me a scrap of fish and show me how to dip it in the salty water for flavor.

“So,” I ask, “is this water higher now than when you were children?” The women giggle and shake their heads. One makes a dismissive gesture with her hand. “It’s nature’s way,” she says. “Nature will take care of us.”

Nature: Sixty-four million years ago, nature raised a volcanic island here. That volcano has long since sunk beneath the waves, but nature saw to it that Funafuti Atoll remained, poking above the surface. About 3,000 years ago, seafarers from the Polynesian kingdoms of Tonga and Samoa, hundreds of miles to the southeast, spotted the land from their outriggers and came ashore. Even though nature decreed that the islands of Tuvalu were to be graced with poor soil, no mineral resources, and little fresh water, the surrounding seas offered abundant fish and, until not long ago, a comforting bulwark against the rest of the world. Islanders slept on open-air platforms beneath thatched roofs, developed elaborate kinship structures to avoid in-breeding, and devised more ways of cooking coconut than seems possible.

When Tuvalu gained independence in 1978, the natural issue it confronted was how to stay afloat financially, not topographically. Unlike other least-developed countries, it proved remarkably adept at hawking its few assets. Despite its modest per capita income of $1,000, the country is in the black-planning to take in, in 2002, about 50 percent more than the $20 million or so that it is set to spend. It sells fishing rights to the U.S., Japan, Taiwan, and Korea for about $10 million a year; it leased the marketing rights to its “.tv” Internet domain name to a Canadian entrepreneur in a much-publicized deal that has so far brought in more than $30 million (the rights were later leased to VeriSign); it adds capital through the sale of colorful Tuvalu postage stamps; and until 2000, it sold its excess phone capacity to overseas sex-chat operators.

Now Tuvalu’s shrewd managers get to calculate the opportunities presented by nature’s grandest, most worrying potential crisis. “In my next life,” says James Conway, Tuvalu’s highest-paid public servant, as he smokes a cigarette on the beach outside his office, “I want to come back as a small island state. All told, it’s a good deal. Virtually all of Tuvalu’s income comes from one source: the idea of nationhood.”

A 43-year-old Californian with degrees in energy economics from Berkeley and the University of Pennsylvania, Conway arrived in Tuvalu 12 years ago as a Peace Corps volunteer, working on a solar and diesel electrification project. He fell in love with the country, not least of all for its glorious fragility; during a storm in 1993, ocean waves swept through his house while he slept. “This is the sharp edge of the climate-change debate,” he tells me. “Forget politicians and scientists and activists. What it boils down to is waves in my bedroom.”

After eight years in Tuvalu, Conway moved to Bonn, where, from 1998 to 1999, he worked as an informal adviser for the International Climate Change Secretariat, a unit of the UN. When he returned to Tuvalu, flush with intimations of the climate change to come, it was in his current, amorphous position as special assistant to the Office of the Prime Minister, a role that he says “commands more power, influence, and respect than I’d ever get back home.” Some islanders feel that Conway cuts a mildly suspicious figure-one person used the term “shadow government.” None, however, doubt his devotion to scheming on behalf of Tuvalu’s welfare. He is widely rumored to be the driving force behind the proposed lawsuit, which he describes as “embryonic,” and he coyly admits to fielding inquiries from Greenpeace “and an array of people in the legal profession who are looking for a toehold to bring action against greenhouse-gas emitters.”

Conway is smart-surely the smartest American politician in Tuvalu. He knows that Tuvalu is not the only nation facing a threat from global warming, and that it can easily be exploited for symbolic purposes, since, as he says, “Tuvalu presents an enticing image for getting the message out to viewers.” But above all he knows that symbolic gestures can sometimes generate real revenue streams. “It’s hard to know in what form global warming will bring in funding,” he reflects. “It’s too soon to tell. But I think it will. Compensation is an issue.”

So, no great global-warming windfall yet. But there’s still time. Conway finishes his cigarette and locks the prime minister’s offices. “Obviously,” he says, swinging his briefcase, “Tuvaluans are hysterically concerned about climate change. But Tuvalu has no leverage, internationally, other than its ability to draw attention to its plight and wake up the world. There’s no such thing as bad publicity.”

We meander along a newly built road. Night is falling, and I offer to buy him a drink. He declines. He has something of a solitary nature, this palagi power broker. “When they make the movie of the story of Tuvalu,” he jokes, “I hope they get Sean Penn to play me.”

SOMETHING DOESN’T quite compute. My head is full of the dire warnings of the government, environmentalists, and the press. But my eyes are open, too, and I can see that Funafuti is no green haven, and that a substantial chunk of its real estate has been cleared of trees and paved, and that garbage seems to be its most prolific national product, and that the environment has been degraded in ways that are unrelated to the legacy of Henry Ford.

Dozens of casual conversations with Tuvaluans who aren’t associated with the government yield little concern about rising seas. Many, like Teagai Apelu, an 85-year-old curmudgeon who is regarded as the leading guardian of Tuvalu’s oral storytelling traditions, are outright scornful of the notion. “There’s no change in sea level,” he tells me. “It’s rumors. It’s lies. It’s always been the same. When it’s high tide, salt gets in the gardens. When storms come, the sand gets washed away in one place and shows up somewhere else. It’s foolish to say Tuvalu will disappear!”

Government officials caution me not to heed the backward views of the people. “Tuvaluans will hide their real feelings when talking to a stranger,” Paani Laupepa tells me. “They don’t want to admit defeat.” Further, he says, 98 percent of his countrymen are devout Christians who take God’s word for it when he promises Noah that the big flood will not repeat itself. Yet after mass at the Tuvalu Christian Church one Sunday, Pastor Molikao Kaua, a diminutive 76-year-old whose blue eyes are so cloudy they seem to be made of smoked glass, tells me that he has made one thing clear to his congregants. “If there is a flood,” he says, “it comes from man, not from God.”

If. Not far from the wharf in Fongafale, a small fiberglass hut suspended over some pilings houses a state-of-the-art sea-level gauge installed by an Australian institute called the National Tidal Facility. Since 1991, the gauge has detected a rise in the waters around Tuvalu of less than a millimeter per year, which is more than a hair but a lot less than a flood. The Australians attribute the unusual high tides that have been observed by some Tuvaluans to a natural tidal cycle in the region that repeats every 18.6 years and is yet to peak. They also point out that the most dramatic recent changes in sea level have actually been decreases, like the astounding one-foot drop that occurred after the enormous pool of warmed-up seawater caused by 1998’s El Ni-o migrated from the western Pacific to the eastern Pacific.

When I mention the Australian measurements to Laupepa, he abruptly shoots them down. “I’m very cynical about Australian science,” he tells me, noting that the Australian government, which funds the National Tidal Facility’s research, is the world’s largest exporter of the second-most-abundant greenhouse-gas emitter-coal. “The Australian mentality stinks,” Laupepa goes on to say. “Their scientists misrepresent information in a way designed to suit the needs of the piper.”

Australia’s director of the National Tidal Facility, Wolfgang Scherer, who developed the sea-level gauges while working in the U.S. for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is adamant that his government has no influence over his Tuvalu project, and believes that objections to his findings are raised by those with “a political agenda.”

Scherer stresses that while the sea around Tuvalu is rising about a millimeter a year, Tuvalu’s troubles are not entirely the doings of nature. They’re also man-made. He cites, above all, “those flaming borrow pits that the Americans put there during World War II when they built the airstrip.” In 1943, 6,000 troops of the U.S. Seventh Air Force arrived and transformed Funafuti into a combat air base to fight the Japanese. The Americans paved one-third of the arable land with a runway that remains the capital’s dominant physical feature, excavating coral from 11 borrow pits across the island to use as construction material.

“Those borrow pits left a mess of the island, and have never been repaired,” Scherer says. “And there’s never been any attempt to give the Tuvaluans anything back for that.” The pits, he tells me, collect runoff and rainwater; this alters the flow of Tuvalu’s fragile freshwater lens, makes the island’s potable water supply salty, and allows seawater to push its way up through the ground. Scherer also suspects that the destruction of the freshwater lens has enhanced the dissolution of Tuvalu’s limestone underpinnings. It’s likely, he says, that Tuvalu is being hollowed out. He compares the situation to that of Bermuda, with its famous limestone caverns, some of which have collapsed. “There’s substantial fear that something like that may be going on in Funafuti, as a direct result, in some cases, of the borrow pits.”

Still, Scherer says he understands where the Tuvaluans are coming from. “In geological perspective,” he explains, “Tuvalu is one of those volcanic islands that has come to the end of its life. It’s largely a natural process. But for an island person living in that environment, a meter and a half above sea level, it’s not a very comfortable experience.”

When I contact Ursula Kaly, an ecosystems specialist who was Tuvalu’s environment adviser for four years, beginning in 1997, what she tells me further complicates the Tuvaluan script for global-warming-wrought annihilation. The gravest danger to Funafuti, Kaly says, comes from tropical storms, and she hints that the island’s vulnerability to storms has been enhanced by things other than global warming. Tree cover, which defends against high winds and soil erosion, has been reduced to make way for construction; reefs, which help absorb energy from incoming waves, have been damaged by the dumping of waste. “It’s just the diffuse impact of everyday stuff,” she tells me, “building houses and roads and gardens, and trying to make a living on this tiny bit of land.”

The most foolhardy assault on Tuvalu’s environmental well-being was sponsored by foreign-aid donors, including the European Union, who encouraged the islanders to remove a bank of coral rocks from Fongafale’s ocean-side shore. The rocks had been dragged to the beach and deposited there by Hurricane Bebe, a fierce 1972 storm that leveled almost every building on the island. “Experts came in,” Kaly recounts, “and said, ‘You’d better dig up that Bebe Bank, or it will be wasted.’ ” A rock crusher was brought in and the bank was quarried for construction materials, including a seawall built on the lagoon side of the island. The seawall crumbled quickly. And without the Bebe Bank to absorb the energy of ocean waves, the island now faces a nasty sucker punch from the next cyclone to make its way ashore.

But hold on: If global warming isn’t the primary agent of erosion, contamination of fresh water, and abuse to the reef in Tuvalu, and if, indeed, the sea’s waters aren’t yet swelling, why is the government mounting a determined campaign to broadcast its death rattle to the world?

One scientist I talked to who has worked extensively in Tuvalu, but who refuses to be named, put it to me simply: If Tuvalu doesn’t stick to the global-warming-is-sinking-us message, it risks losing access to whatever compensation or assistance might be coming its way. “Even if they’re not 100 percent sure,” the scientist said, “they’re going to have to talk as if they are in order to get heard. . . . I’ve been to a lot of international meetings. If you let into one of those big UN meetings even one little quiver of doubt, you get cut out. So you see, the system has created them.

“I’d be worried about being on Funafuti now if another Bebe came through,” the scientist continued. “I think the stage is set for a real disaster now. Resilience has been taken out of the system-because trees are gone, because the coral reef hasn’t grown back yet, because people pick up rocks, throw rubbish, build houses. There is a sense of overall ecosystem downgrading. Worrying about climate change is like a terminal cancer patient worrying about catching AIDS.”

SO, TUVALU IS GOING DOWN. If not today, then tomorrow, and if not because of a single high-profile cosmic phenomenon, then because of a set of murkier, more depressing, mundane, typically human facts. Global warming may not, at the moment, be flooding Tuvalu, but globalization is. Either way, Tuvaluans are searching for deliverance.

Change has come with staggering speed. As recently as 1978, most Tuvaluans got by on fishing and farming. Although islanders can still be seen walking down the road every afternoon toting huge freshly caught tuna, 70 percent of the country’s food is now imported, and tin cans and plastic bottles float in the borrow pits, line the roadsides, and clog the beaches. As a cash economy replaced a subsistence economy, residents of the eight outer islands, which are far less developed and far more pristine, flocked to Funafuti, seeking jobs in the new national government. With 4,500 people crammed in, Funafuti’s population is now five times larger than it was in 1973.

The overcrowded conditions and limited economic prospects only help to feed First World doubts that global warming is the real source of Tuvalu’s pleas. “We’d take Tuvalu’s position on global warming a little more seriously if the first thing they’d done wasn’t to ask Australia and New Zealand to let them in,” an official in the U.S. Embassy in Fiji tells me. “Of course they want to move. There’s nothing for them there.”

When I met him, James Conway assured me, almost apologetically, that “if a court system were to say that there’s evidence of sea-level rise and that industrial greenhouse gases were responsible for it, and if that court gave Tuvaluans a choice of half a billion dollars or the ability to continue to inhabit their islands for the next thousand years, they’d choose the islands in a minute.”

They won’t be given that choice. Nature and human folly and the internal combustion engine will, at some point, conspire to rid the world of a land that few people knew existed. There’s unlikely to be a court case at all. The costs are too high and the odds too slim. And some environmentalists are already beginning to distance themselves from Tuvalu’s grandstanding. Lester Brown, president of the Earth Policy Institute, issued a press release in November 2001 alerting his constituency that “Tuvalu is the first country where people are trying to evacuate because of rising seas.” Nine months later, when I call him, he admits, “I guess what we were looking for is some canaries in the coal mine, and at first Tuvalu looked like it might be a canary. On closer examination, it’s not clear that it is.”

IF IT WERE UP TO ME, I’d give them the half-billion and throw a big farewell bash. Maybe it would look a little like the election-night party I attend near the end of my stay, at the house of Kamuta Latasi, the feisty 66-year-old former prime minister who, as a member of the opposition in parliament, is looking for a return to power. Dozens of relatives and supporters are sitting on plastic lawn chairs in his yard drinking Chinese beer. A pair of pigs are roasting in the ground beneath a tarp, and a sea turtle, still alive, flails in its overturned shell, awaiting its turn on the coals.

Latasi, who is known as “the old warrior,” was driven from the highest office in 1996 when he insisted on removing the Union Jack from Tuvalu’s flag. He is a staunch nationalist who would prefer that the government focus its efforts on planting coconut trees, improving schools, and restoring some of Tuvalu’s peaceful life, rather than on getting caught up in international affairs.

“When I was prime minister,” he says, standing by the above-ground concrete tomb of his father beside his front porch, “I was very strong on suing the U.S. and the British for damage they did to us during the Second World War. But why are we trying to do this new lawsuit?”

Latasi tosses an empty beer can at a stray dog that is licking leftovers from a paper plate. “I believe that climate change is happening, of course,” he says. “Deep in my heart I know that something has gone wrong here, and it must be the work of man, and not just nature. But who are we? Tuvalu is powerless. How can we stand up to the might of the industrialized world? We’ll be a laughingstock.”

At midnight we learn that Latasi is reelected to his seat in parliament, but that he will be unable to build a coalition to support his bid for prime minister. “Please remember,” he implores me, “that Tuvaluans are human beings, not just hungry animals on a rock.”

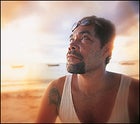

The night wears on and the party descends into a raucous, drunken free- for-all. Before I stagger away, I meet a burly man named Siligama Taupale, dressed in dirty jeans and a white tank top inscribed with the words tequila sunrise. Siligama is 38, but he might as well be as old as Tuvalu, because his story of disaster and survival, incredible as it sounds, is a useful reminder that truth and myth are not easily disentangled on this island.

At sunset on May 14, 1997, Siligama left the harbor at Funafuti in a 16-foot plywood boat with a 40-horsepower outboard motor. He was going tuna fishing just beyond the atoll, near the islet of Fualefeke. When night fell, he put down his anchor, consisting of a stone entwined in a rope. He started drinking “hot stuff”-hard liquor-and fell asleep.

“I wake up and see no land,” he recalls.

“The anchor broke. My mind say, ‘Don’t worry.’ But where’s Funafuti? For two days, no worry.” He had no compass and no flares, only a hand mirror to reflect the sun’s light. “Yeah, I get afraid. I think, ‘I’m dead.’ I don’t want to die.”

After three days Siligama spotted a fishing vessel. He had saved enough gas to power his way over to his rescuers. “I see them and I say, ‘Please help me, please help me.’ But they no help. I write the name of that boat in my boat with a screwdriver: Young Star. After that I stay in my boat crying.”

Who knows why Young Star didn’t come to the aid of the fisherman? Perhaps its crew members were busy with their own affairs. Perhaps they didn’t believe he was in genuine peril. Siligama saw more boats over the next weeks and months than he can remember, but he gave up asking for help. He didn’t care about dying anymore.

He ate fish and birds that he caught with his hands. He drank rainwater from the floor of his boat. He sucked on his beard, which had grown down to his chest, for any moisture that gathered there. His clothes disintegrated. He spent hours staring at a tattoo on his shoulder of a woman’s face. “Sometimes in rain-very cold. Sometimes in sun-very hot. Big waves come, big storms. I talk to God. I see my daughters’ faces everywhere, in sky, in water, in bottom of boat.” He goes silent and begins to move away from me. “I don’t want to tell my history,” he says. “It make me cry to remember.”

After five months and three weeks adrift, he was spotted by a Korean fishing boat, the Logas, near Christmas Island, about 1,800 miles east of Tuvalu. The Korean boat took him aboard. He couldn’t walk or keep down food for several days. “Thank you to the Logas for your help to me,” he says, as if I were the one who had saved him.

Siligama was afraid of the ocean for a while. To get by, he took odd jobs working construction. But he still goes out fishing when he has to, which is pretty often, in order to put food on his family’s table. He has stayed in Tuvalu, though what he’d really like to do is move to New Zealand. Perhaps one day the government of New Zealand will grant his wish.