“HAVE YOU EVER wondered what it feels like to be an astronaut?” asks our pilot, Bertus Schoeman. The question is out of the blue聴literally. We've been cruising through crystal skies in virtual silence for the past half-hour, too rapt with the passing panorama of honeyed dunes and roiling, black Atlantic waters beneath us to bother with speaking. Before anyone has time to respond, Schoeman throttles the engine and jerks the nose of the four-seater Cessna 210 into a Virgin Galactic聳esque trajectory.

Namibia safari

Namibia safari

GOLDEN DAWN: Early to rise in the open-air chalets at Wolwedans.

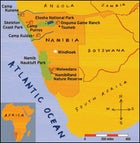

GOLDEN DAWN: Early to rise in the open-air chalets at Wolwedans.It's a sunny afternoon on the Skeleton Coast, a 500-mile-long strip of gnarled basalt and wind-sculpted sand in northern Namibia, and the massive landscape is blotting out the high-pitched whine of the plane's small engine. Photographer Jen Judge and I are on board one of the most sweeping safaris on the African continent, Namibian Encounters, a new ten-day flying excursion that takes in the country's finest other-worldly landscapes, from the Namib Desert in the south to Etosha National Park in the north, with a Skeleton Coast flyover along the way.

At the moment, however, all I can see is the immense blue sky as the plane hurtles away from the ground. Just when my jitters are heading for full-fledged panic, Schoeman suddenly veers the aircraft earthward. For a moment we all hover, weightless, out of our seats. Jen's seat belt, which she's loosened just enough to maneuver around while taking photos, hangs in a swooping arc above her lap. Schoeman's head presses up against the ceiling. Pebbles and a bronze coin that lay on the dashboard an instant earlier are now suspended in space. Then it's over. The plane has leveled, Schoeman is quietly explaining that Ron Howard used that stunt to obtain weightlessness in Apollo 13, my stomach has eased out of my throat, and Jen and I are grinning from the thrill. “This is no commercial flight,” Schoeman concludes in his Afrikaans deadpan.

NOT ALL COUNTRIES' safaris are created equal. For herds so big they're hard to count, head to Kenya. If the wildebeest migration is your thing, try Tanzania. And Botswana is where you go for to the privilege of spotting game in isolation, followed by the pleasure of retiring to no-amenities-forgotten accommodation.

Then there's Namibia, which isn't overflowing with animals but still hosts reasonable populations of lions, leopards, elephants, rhinos, giraffes, cheetahs, and all manner of antelope. And while it may not be brimming with wildlife, Namibia isn't exactly stuffed with much of anything else either. There are fewer than 1.9 million Namibians聴less than one-ninth the number of people living in greater Los Angeles聴scattered across a piece of land roughly the size of California, Oregon, and Washington. In Namibia, desolation is exactly the point: Few places on the continent can compete with the country's immensity of open space; almost none have such a physically alluring landscape that's so completely untamed yet still relatively accessible. “It's Africa for beginners,” said Stephan Bruckner, a polished 39-year-old Namibian entrepreneur and the managing director of the chic new Wolwedans Lodge, in the Namib Desert. “The country is clean, the infrastructure is in good shape, and everything works.”

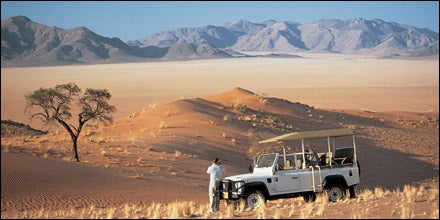

We have traveled to Africa to make a counterclockwise loop of Namibia in small-engine Cessnas. The trip would take at least a month if you rattled it out in a safari-ready 4×4;

“'Safari,' in Swahili, means 'journey'; it has nothing to do with animals,” notes author Paul Theroux at the outset of Dark Star Safari. “Someone 'on safari' is just away and unobtainable and out of touch.” Etymology aside, people expect animals when they go to Africa. Which is part of why I signed on: Could a winged safari over a constantly shifting landscape where the game isn't necessarily the focal point really merit an eight-grand price tag?

WILDLIFE SIGHTINGS MAY NOT BE GUARANTEED, but we spot our first game just hours after arriving in Namibia. As we make our final approach to Wolwedans, Dave Bradbrook, the 32-year-old pilot at the controls of our plane, begins to mutter: Five hundred feet away, loitering squarely in the middle of the runway, stands the country's national animal, a 400-pound, painted-face antelope called the oryx. We're tracking a path to flatten our first attraction.

Three hundred feet later, our wheels touch down. The oryx doesn't budge.

We've landed on the NamibRand Nature Reserve. Like so many private parks and ranches springing up around Africa, the reserve, on the eastern boundary of Namib Naukluft Park, effectively expands the amount of protected land by creating a 695-square-mile buffer zone for the adjacent park while simultaneously capitalizing on the stream of visitors it generates. At the heart of the NamibRand sits Wolwedans, a collection of three small luxury lodges balanced on shifting red desert sands.

Part of a safari's appeal is living out the expatriate dream of affluence and ease: relaxing with a book in the oak-and-leather hunting room, sipping a rock shandy under the lazy twirl of a ceiling fan, lolling carefree about the expansive property. Wolwedans specializes in this opulence. The simple eucalyptus-and-canvas chalets and lodge emanate colonial elegance, with tables set in crisp white linens and silver, rich mahogany furniture, and flaxen light cast by oil lanterns. The cuisine is decidedly Old World as well聴one night we eat pumpkin mousse in puff pastry, beef consomm茅 with wild boar ravioli, and pan-fried zucchini served over an oryx steak. (It seems not all oryx get off the runway fast enough. In fact, Bruckner later tells me that game, including antelope, zebra, and even crocodile, is farmed widely throughout the country, just as cows are raised for meat in the United States.)

Easing into the reverie is a decidedly sluggish program: breakfast on the deck, a morning drive in the park, an afternoon nap by the pool, another Land Rover tour when the heat recedes, and finally a four-course wine-and-game extravaganza that stretches into the night. With the exception of small herds of oryx, zebra, and springbok, a sleek brown-and-white miniature antelope, we don't see much game on our drives. But who cares when each evening's tour wraps up with a dune-top repose, accompanied by nosh and Sapphire-and-tonic sundowners.

Our last night in the Namib Desert, Jen and I dine with Bruckner, who tells us about a remote lodge he's building on the far side of the reserve. When the main course is served聴a springbok steak in a balsamic reduction聴the trip's purpose rushes into focus. I might not be able to expand my life list of animal sightings, but I'm doing a pretty good job polishing off a menu's worth of them. As Bruckner explains game management and Jen knifes into her steak, I quietly christen the trip a culinary safari. After all, I'm less likely to spot the Big Five than to eat my way through a delectable five of oryx, springbok, ostrich, kudu, and zebra. Two down, three to go.

“DON'T EXPECT TRANQUILLITY ON THIS NEXT STRETCH,” says Schoeman as he whisks my backpack from Wolwedans' dirt runway into the plane's small cargo area. “No more sitting around.”

No one knows the Skeleton Coast better than the Schoeman clan. Louw Schoeman, a lawyer who moved his family to Windhoek from South Africa in 1958, discovered the scraggly

The Skeleton Coast's landscape of burnished dunes and capricious shoreline is especially breathtaking from the air. In our first hour, we fly over Sossusvlei; from above, this collection of some of the world's largest sand dunes (more than 1,000 feet tall) looks like a giant swatch of swirled velvet. After the dunes we slip lower, not even 300 feet off the ground, where it's easy to spy colonies of seals wallowing on the shore and a thousand-strong flock of iridescent pink pelicans, which startle into flight at the clatter of the engine.

“How about a picnic on the beach?” Schoeman suggests, tipping the plane gently toward a stony stretch of windswept coast. I'm amazed he can land on such rough terrain, and I ask whether he's allowed to touch down wherever he likes. “No, not really,” he says, bringing the plane in gently. “But anyway, I like to.”

The beach we've landed on聴site of the Toscanini Diamond Mine, last active in 1968聴is聽littered聽with remnants of the past. A rotting longboat serves as a makeshift den for a family of jackals, and two rusting cast-iron vehicles with spoked wheels protrude from sand drifts. Up the beach, an arching whalebone聴picked clean by animals聴gleams white against the dark sea. The Skeleton Coast takes its name from remains like these: the shipwrecks, derelict settlements, and carcasses scattered along the coastline. Over the years, dozens of ships and planes have been lost on these shores, driven off course by the furious Benguela Current churning up from the south and stymied by dense sea fog and shifting shoals. It's a lonely, storm-scoured place, and for a few moments we seem cut off from everything. Which is exactly why I've come: Unlike the castaways before me, looking for any possible way out, I'm here to purposefully maroon myself. As I listen to the waves chip away at the shore, I feel tiny and distant and completely content.

After we wander the beach, Schoeman lays out sandwich fixings for lunch聴including kudu carpaccio. I stuff a slice of smoked antelope into my mouth and taste it melting on my tongue. It's rich and tangy and slightly gamier than oryx.

We make our way up the coast, then touch down in wild isolation. At Kuidas Camp, Schoeman leads us on a hike into the stony red hills to show us the rock paintings he and his brother Andr茅 found when they played here as children. Farther north, at Rocky Point, he recounts stories from the day his family first visited the beach and found a littering of broken porcelain, which they later discovered was the remains of a 17th-century galleon shipwreck. Schoeman tells the stories quietly, as if he's confiding in us. This may be a guided safari, but these insights make it feel like a trip with an old friend on his bygone stomping ground.

At the Kunene River, just across the border from Angola, we take a waiting Land Rover over a long, gentle grade of dunes into the Hartmann Valley, a vast, sandy, mountain-ringed basin named for German geologist Georg Hartmann, who spent six years surveying the region in the late 1800s. More than once, Hartmann and his team became stranded and nearly succumbed to these bleak surrounds. Partway up the slope, Schoeman cuts the engine and we sit in silence for a few moments. Like everywhere on the Skeleton Coast, the spot is empty, remote, inaccessible, and much like the frontier it was a century ago. This is one of the few places in the world where you can still experience land like this. “Can you imagine being stranded here back then?” Bertus asks. “No food, no water, no shelter from the harsh sun. Just imagine it.”

IT'S 1 P.M. WHEN WE lift out of the Hartmann Valley, and there's nothing stirring in the midday swelter except the cloud of red dust the plane kicks up. As we drift higher, the cooling air blows away the heat and desert gives way to savanna聴first, dots of scrub begin to speckle the earth, then lone acacia trees, and finally fields of green. Next stop, Etosha National Park. Despite the earlier dearth of game (aside from the grilled and braised varieties), the final days of the Namibian Encounters safari afford the best chances of seeing wildlife.

After Schoeman drops us in Tsumeb and buzzes away toward stacks of billowy cumulus to the south, we throw our kits in a pre-arranged rental car and race westward on freshly sealed tarmac roads聴a far cry from the mud-choked dirt tracks that pass as “highways” in many countries on the continent. Just before the Etosha gate, we make a hard right on a dusty two-track and almost mow down a zoot-suit herd of zebra. We've arrived at Onguma Game Ranch.

Once a cattle-and-eland ranch, Onguma has been redeveloped as a tourist lodge on a private game reserve聴like Wolwedans, it's another example of the strategy to buffer public parks with privately held reserves. The ranch centers around the new Tented Camp, a half-moon-shaped lodge with a deck surrounding a spring-fed watering hole. As it's once again sundowner time, we order vodka sodas with lime in the main lodge and head for our private “tent”: half walls built from rough-hewn limestone bricks, his-and-her stone washbasins, and an elegant stainless-steel interpretation of the zinc bathtub, all set under a 20-foot-tall wave of flowing, cream-colored fabric. We draw a bath and settle in with our cocktails, watching springbok flit nervously around the watering hole.

Over dinner that night, we have our second game encounter at Onguma: a mouthwatering cut of ostrich stuffed with crispy leeks and bacon and drizzled with a garlic-and-sweet-onion reduction. I wash the bright-red meat down with sips of a full-bodied merlot. Juicy and rich like filet mignon, but more dense and substantial in my mouth, ostrich is much preferable to zebra, which I'll sample a few days later at a leafy terrace restaurant in Windhoek. The zebra is stringy and tough, and when I try to place the flavor, all I can conjure is the boggy grasslands the animal traipsed through. Some game, it seems, is better left for viewing.

In Etosha, Jen and I search for that wildlife vibe, gawking at aloof animals from the comfort of a Land Cruiser. Our first morning in the park, we stumble on several elephants聴in fact, one nearly bumps into us. Having sighted the behemoth across the savanna, we turn off the car's ignition to watch and are amazed when the old bull barely breaks his stride as he angles around our car, swishing the exhaust pipe with his tail. Considering that the “little rains” have just begun, it's a lucky sighting: With water more readily available, the animals will begin scattering across the park, leaving hapless tourists like me with unfinished tallies.

Luckier still, the next day we happen upon a pair of lions at a watering hole聴he lounging listlessly under a tree, she pacing around the veldt with the self-assured swagger of an athlete. The big-game allure becomes clear: Unlike watching smaller, jumpier prey, which can quickly fall into a slightly awkward and tedious I'm-looking-at-you-looking-at-me-looking-at-you routine, it's easy to spend the afternoon studying a trophy animal in its environment. The poise and grace of these large beasts is engrossing.

And yet even this up-close encounter with the mightiest of all animals feels controlled and insignificant compared with the intensity of the constantly moving sands and relentless surf a few afternoons earlier at the Toscanini Mine site. “This is how I want you to remember the Skeleton Coast,” Bertus had said evenly, gesturing with both arms to the expanse around us. He continued speaking, but a gust of wind suddenly kicked up and his words were swallowed by the giant stretch of desert and sea.