Roger Robinson is nine��years old, living in London in 1948, at the beginning of ��($25, Syracuse University Press). Life looks gray, it chills to the bone. His mother pushes a baby carriage to collect coal, wending past rubble and bombed-out buildings. Money is scarce, and family meals are spare. “I still remember my first banana,” Robinson writes, nearly 70 years later.

A couple from his neighborhood, the Lutterlochs, invite him to the Olympic Games that summer. This sounds nice, though it strikes no particular chord at the time. It has been 12 years—longer than his lifetime—since the last Olympics were held, so he understands little about them.

In vast Wembley Stadium, Mr. Lutterloch tells a young Robinson how to watch the 10,000-meter race: look for the Finns in their immaculate blue-and-white colors. True to form, they lead imperiously for nine laps. Then a surprise: a new leader, in red and white. “He was a strangely awkward runner who seemed to be forcing himself along, scowling and writhing,” Robinson writes. It’s Emil Zátopek. How lucky can you get? At his first big track meet, the kid gets to watch the greatest distance runner of all time. This seems propitious indeed.

The invincible Czech, who will go on to win the 5,000 meters, 10,000 meters, and the marathon in the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, is already a force. “His face was still grimacing, and his upper body pitched and rolled, but his legs! His legs were magical. His knees lifted high but turned over fast, like the pistons of the steam locomotives that rushed by at the back of our house,” Robinson writes.

At his first big track meet, the kid gets to watch the greatest distance runner of all time. This seems propitious indeed.

To Robinson, Zátopek seems a gentle soul as well. He doesn’t glare dismissively at the runners who��he laps; he gives them an encouraging pat on the back. “For me, it was the moment I discovered something I wanted to do, and do well,” Robinson writes. “Zátopek showed me running.”

Robinson proves an exceptional acolyte. In the seven decades since 1948, he has raced against some of the world’s best��and excelled as an over-40 marathoner through��the 1980s, winning his age group at Boston and the New York City Marathon. He has also covered the sport as a track announcer, journalist, and book author.

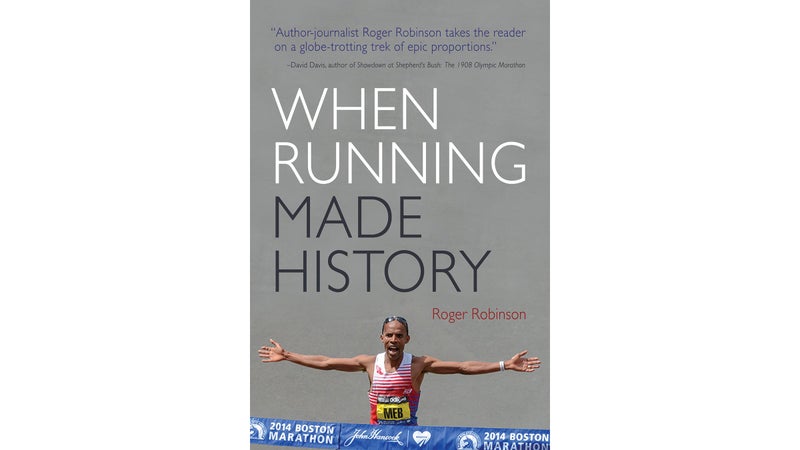

Among Robinson’s previous works, rests high on my office bookshelf. It sets the standard when it comes to finding running references from the Bible, Homer, Shakespeare, and even James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. But I believe When Running Made History is Robinson’s best and most significant running book. It digs into every important topic: transcendent individual achievements, the late-1970s running boom, the explosive growth in women’s participation, the East African miracle, running and the environment, and the connection between aging, health,��and masters running. Robinson is the perfect guide—engaging, informative, thought-provoking, even funny. Because the book came from a university press, it was largely overlooked when first published last year. But it deserves to be picked up at any time,��for its historical sweep and cultural context.

Robinson has a knack for showing up at pivotal moments: in the 1960 Rome Olympics,��Buddy Edelen’s American record marathon at Chiswick, England, in 1963,��Ron Clarke’s world-record two-mile race in 1965,��,��the ,��the Kenyan sweep in the 1988 World Cross-Country Championships, and��the , in 1996.��

These are races of supreme athletic breakthrough��but, more importantly, of tidal change in the sport. Robinson sees the big picture. Bikila and the Kenyans presage the East African domination of distance events in the last three decades. Clarke sends Robinson and friends to the pub, scintillated��but also stunned. They realize “the sport we loved and labored at was never going to be the same.” To keep up, they would have to train like Clarke—far harder than they had ever imagined.��

The Avon race paves the road to the first women’s Olympic Marathon four years later. (And introduces Robinson to his future wife, running pioneer Kathrine Switzer. They married in 1987.) When the 1996 Boston Marathon crams 36,000 runners into bucolic Hopkinton, Massachusetts, anyone can��see��that running has graduated to a grander stage.

The stories grow more personal, and more riveting, when tragedy strikes. On September 11, 2001, Robinson and Switzer gaze south from their apartment on Central Park to see “from downtown, a gray-yellow smoke-cloud slowly rising, drifting, and spreading.” They head to a local Red Cross center, hoping to help, but are rebuffed. (Their blood type isn’t needed.) Dazed and shaken, they resort to habit��and do the unthinkable: they lace up and run.

Robinson tells me he considers this perhaps the most expressive section of the book. “I aimed for writing that was like a sorrowful, thoughtful piano, with tragic mood sometimes verging on lyrical or defiant,” he says. “But mostly falling cadences and melancholy meditation.”

He reminds us that the 1972 Munich Olympics refused to buckle after 11 members of the Israeli Olympic team were taken hostage and killed, and that 400 years ago, Shakespeare’s Henry V exhorted,��“When the blast of war blows in our ears/Then imitate the action of the tiger/Stiffen up the sinews, summon up the blood….”��Robinson’s run through Central Park on the afternoon of 9/11 stretches over several pages. I am most struck by these unpretentious words:

“On such a day, you’re not sure what is appropriate. There are no precedents. By running we declined in that simple way to comply with the plot to disrupt our lives by force. The dogs were out, too, and children in the playground, though even they seemed to play more quietly.”

These are races of supreme athletic breakthrough��but, more importantly, of tidal change in the sport. Robinson sees the big picture.

We live in partisan times, to borrow a Beltway phrase. After the cancellation of the 2012 New York City��Marathon due to Hurricane Sandy, and the fatal��explosions near the Boston Marathon finish in 2013, every runner yearned for a celebratory Boston in 2014. Of course, we didn’t dare hope for an American winner, not with all the East Africans in town.

Yet even that happens. Meb Keflezighi, born in Eritrea but a U.S. citizen since 1998, scrawls four names in the four corners of the race bib on his chest—the four who were killed a year��earlier. He races as if possessed. In reality, Keflezighi��has spent 20 years, since junior high school, preparing for a day like this. “Symbolic victories in sport don’t happen because the rest of us are craving a symbol,” Robinson reminds us. “They come because someone has done the work and delivers at top level.”

There’s a more important message. Many countries have been riven by divisive immigration controversies, “with millions desperately seeking opportunity or safety, received often with fear and hatred,” Robinson reminds us. “Keflezighi’s historic win reads as a defiant riposte. A refugee, he is a member of a large immigrant family making huge contributions to American society.”

Robinson himself loves to train hard and race his guts out, but he had his most rapturous run when injured and slow at the 1990 Berlin Marathon—the first to pass into East Berlin. Under the Brandenburg Gate, he stopped for photos, patted the stonework, shook hands with strangers, hugged everyone in sight, and “got kissed by some soggy bearded foreigner.” Wish you were there? Me, too.

In his introduction, Robinson quotes Dickens, explaining that he has written from “the broken threads of yesterday”—that is, one’s imperfect memory. He need not apologize. When Running Made History reads like a tight, artfully woven tapestry. It’s one of the best running books ever written—if not the very best.

Amby Burfoot won the 1968 Boston Marathon��and has been writing about running and fitness since 1978. His most recent book is Run Forever: Your Complete Guide to Healthy, Lifetime Running.