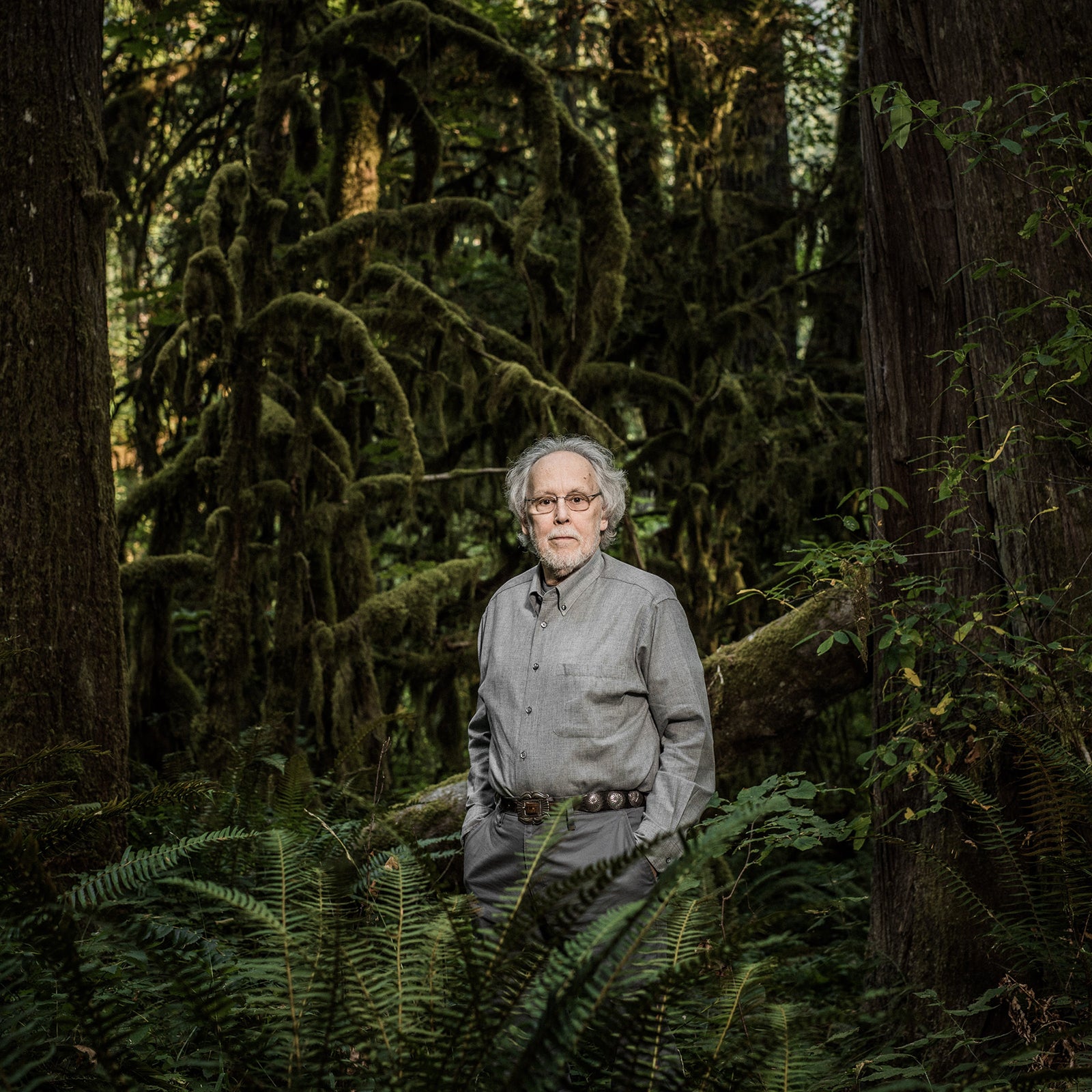

I was on Skype with , legendary scribe of the natural world, when the ravens interrupted. As cawing sang through my computer, I pictured dark wings skimming Lopez’s home in the Oregon rainforest, where he has lived for almost half a century. Earlier that morning, a raven had cruised past my cabin near the British Columbia–Alaska border, and the two felt somehow connected.��

I heard fumbling in the background. The cawing stopped. “It’s my cell phone,” Lopez confessed. One of the perks of a raven ringtone, he told me, is that when it goes off in a crowded room, instead of glaring at him, people look to the nearest window to locate the birds.��

Lopez, at 74, is a master of making us look outside—at hypothetical corvids through glass, but more often, through his words, at the complicated place of humans on a living planet. Born in New York and later raised in California, he is best known for his 1986 National Book Award–winning , a natural history of northern landscapes and lives, and how human desires have shaped and been shaped by them. He had authored five other acclaimed books by then, and went on to write ten more, from short stories to essay collections, all with striking lyrical and moral power. But none displayed the scale or ambition of Arctic Dreams, and the problem with writing a modern classic is that people clamor for another.

More than 30 years later, after traveling from pole to pole and bearing witness to a world under crushing pressure—and after being diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer several years ago—Lopez has delivered ��($30, Knopf). This epic narrative details his journeys in the Pacific Northwest and the Galápagos Islands, equatorial Africa and Tasmania, the Arctic and the Antarctic, and lands between and beyond. En route, Lopez reckons with human calamity, searches out other ways of knowing, and contemplates the meaning of horizons—places actual and metaphorical where the earth meets the sky and knowledge meets speculation. By turns unsettling and sublime, Horizon is a bracing masterpiece for a broken world. It is also Lopez’s most autobiographical work, in the sense that he’s the companion we travel with on the page. But the “throttled Earth,” as he puts it, is ��ǰ������Dz�’s true protagonist, and at stake is our collective future on it.��

He’s the wise elder we all wish lived just down the road, so that we might swing by and, in the spaciousness of his presence, repair our sanity, our sense of what we want our lives to mean.

In person there’s a quiet courtesy to Lopez, a sincerity and sense of measure that seems almost rebellious in this age of high-octane oversharing. Certainly, it’s hard to imagine him ever deploying a hashtag. When he speaks, radiant sentences unfurl like an opening in fog. “We need maps that make evident and resplendent the earth,” he mused when I first met him, at a conference in Lubbock, Texas, in 2012, because that is the sort of thing he says in casual conversation. It’s also the sort of thing he does, with books that collectively wake us up to the immense world outside our small, frazzled selves. He’s the wise elder we all wish lived just down the road, so that we might swing by and, in the spaciousness of his presence, repair our sanity, our sense of what we want our lives to mean.

On a planet coming unhinged, we need these heart-to-hearts with Lopez more than ever. Horizon distills a lifetime of them. This is the place we now stand, he is saying, and from here the skyline looks hazy. To put it bluntly, as Lopez does in the prologue, “What will happen to us?” If worshipping knowledge, money, and power over wisdom got us into the mess we find ourselves in, do we still have time to get wise? “We can throw up our hands and say what’s the point,” Lopez told me when we talked this winter. “But my urge is to not lose faith. We’ve never truly tested the human imagination.”��

Often it takes��a crisis to make people go that deep, to ask the big questions. Yet Lopez has always lived and written with shamanic intensity. People have chided him for taking the world too seriously, but how else, he writes, “could you take it?” Plus, seriousness for Lopez doesn’t preclude an enthusiasm for life, or raven ringtones, or ripping full throttle across the Ross Ice Shelf to test snowmobiles before a scientific expedition. (He admits this was “more testing, perhaps, than they really might have needed.”) Horizon is a grave and demanding book, but it isn’t humorless. When Lopez visited the South Pole, he brought a tubular map case that made his bureaucratic handler suspicious. Lopez joked that it contained a fly rod, that he wanted to “make a few casts” on the polar ice cap. No less bizarrely, the case actually contained a kite. At minus 26 degrees, and in defiance of his handler’s dictums, Lopez flew it over the , his “whimsical and private gesture of disagreement” with the presence of national markers on a continent that belongs to no one.

Gestures matter to Lopez, even those that might be meaningless by empirical measures. In Arctic Dreams, he famously bowed before the nest of a horned lark, and in Horizon he bows before the world’s griefs and its almost unbearable beauty. Such as the sun burning inside a glacier “like a lightbulb shining through a parchment shade.” Or the fallen bits of the moon, the asteroid belt, and Mars he sees constellating polar ice sheets. Or the small caverns breathed into the underside of sea ice by surfacing Weddell seals. Surfacing in one himself on a frigid scuba dive, Lopez removed his regulator to inhale the “vaguely fishy air of multiple seal exhalations.” Horizon never flinches from sadness or disintegration, and never offers false hope; yet reading it leaves you feeling revived, far from alone, and part of a larger unfolding.

“My urge is to not lose faith. We’ve never truly tested the human imagination.”

When I ask Lopez what’s next for him—that dreaded question for authors who’ve just finished books, never mind a book that took three decades and an entire lifetime to write—he’s vague on the writing front. He’s got some ideas, he says, but what he really wants to talk about is hopping in his truck and heading north. He wants to drive to the dead end of Alaska’s North Slope Haul Road, now known as the , one of the roughest and remotest tracks in the world, which begins near Fairbanks and finishes near the Arctic Ocean.

He’s in no rush to get there. Setting off from home, he’ll linger in wilderness where he finds it and pay respects to indigenous communities along the way. Mostly, he intends to listen. Without an agenda, without a plan, and without expectations, he hopes to hear, as ever, what the quiet world has to say.��