In May, Peter Jensen, an environmental coordinator for Patagonia who’s based in Salt Lake City, embarked with a colleague on a three-day backpacking trip through the Upper Paria River Canyon, a picturesque red rock canyon in southern Utah. “The place is magical,” Jensen told me. “It’s a wilderness in the true sense of the word.”

Jensen was entranced by the scenery, but dismayed by what he saw at his feet. The Upper Paria is one small piece of the more than 850,000 acres cut from the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument by Donald Trump in December 2017. For the entire 35-mile route, Jensen said the land had been badly scarred by the hoofs of grazing cattle and the waffle-iron treads of off-road vehicles. (In spite of being removed from the monument, the canyon remains a wilderness study area and therefore off limits to vehicles.) “On almost every terrace and meander bank there were multiple vehicle tracks,” Jensen said. “In some places they were six to eight inches deep and went right through cyrptobiotic soil and cottonwood groves.”

Since President Trump issued an order to shrink the Utah monument last winter, I’ve heard numerous reports from local residents, hikers, activists, and land managers of flagging oversight and mounting damage to the area’s fragile landscapes and cultural sites. One local resident who wished to remain anonymous told me he spends hundreds of hours in the backcountry and has seen a notable increase in vehicle traffic on closed routes and across formerly untrammeled stretches of land, presumably by visitors “who think Trump's action has opened it all up for cross-country driving.” Ace Kvale, a Boulder resident and photographer, concurred and said he fears the Grand Staircase is “becoming another Moab…People moved here to avoid that very thing.” ������������������

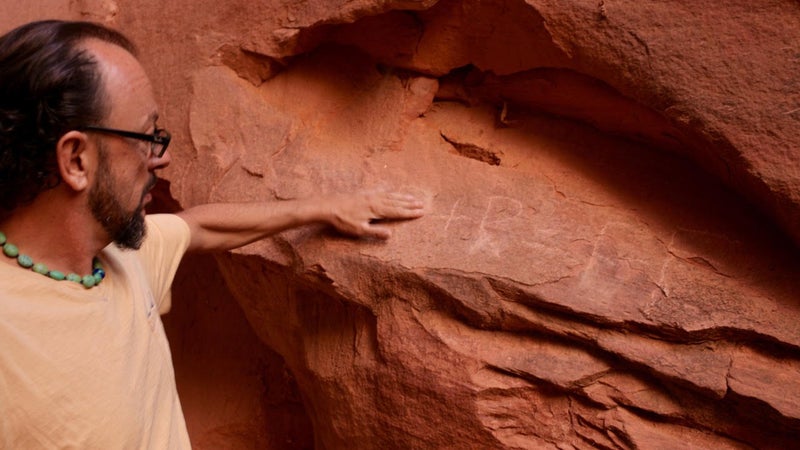

Curious to see the alleged damage for myself, I contacted Colter Hoyt, a backcountry guide in Boulder. On a mid-August day punctuated by thunderstorms and flash floods, we explored a small cross-section of the lands cut from the monument by Trump’s proclamation. Near an unmarked archaeological site tucked away in a side canyon we came upon a soiled pair of underwear and a streamer of toilet paper stuffed under a pile of rocks. “Just gross,” said Hoyt. “But it’s the sort of thing we’re seeing everywhere now.” The next day, on a vast expanse of slickrock, we watched a man and woman fill a shopping bag full of round rocks known locally as “Moqui Marbles.” These iron oxide concretions form deep within the sandstone and tumble out over millennia—like raisins liberated from a carrot cake—as the surrounding rock erodes. “It’s a crime to take even a single one,” said Hoyt. “But, hey, who’s looking these days?” In recent months, Hoyt says he has encountered graffiti on petroglyph panels, bullet-riddled trail signs, ATV tracks in restricted areas, and heaps of garbage in the backcountry.

Some might chalk up this unfortunate state of affairs to the area’s rising popularity—the inevitable price of staggering beauty in an increasingly crowded and digitally interconnected world. In 2017, the Grand Staircase received close to a million visitors—nearly double the number who visited in 1996, the year of the monument’s founding. But Hoyt and other locals claim that much of the bad backcountry behavior is politically motivated, fueled by Trump’s anti-public lands policies and the rhetoric of Utah representatives Rob Bishop and Orrin Hatch, who over the years have sponsored legislation to weaken environmental protections and transfer federal lands to the states. “There’s a growing sense around here that anything goes,” said Hoyt. “That you can use and abuse the land because the highest officials in the country say you can.”

Nicole Croft, executive director of local non-profit Grand Staircase Escalante��Partners, echoes Hoyt’s sentiments. Earlier this year, one of her colleagues hiked into an idyllic canyon called Harris Wash, where she followed a set of ATV tracks for miles through the sandy creek bed. (Vehicles are not allowed past the trailhead.) “I couldn’t believe it,” she said. Immediately following the downsizing, she said she received dozens of reports of vandalism and damage from sections of the monument cut out in the executive order. More disconcertingly, she said she received reports from areas still well within it. “It’s as if certain members of the public are perceiving this as a major demotion of these lands.”

The mounting damage is of a piece with what many locals see as the Trump administration’s larger goal of reducing federal oversight of public lands and opening them up to increased mining, drilling, and ranching. According by the Huffington Post, over twenty mining claims have been made within the boundaries of the Grand Staircase since Trump’s decree. In June, Hoyt blew the whistle on the acquisition of an abandoned copper and cobalt mine by Canadian mining outfit . The mine, known as Colt Mesa, which lies on a rough and remote dirt road some forty miles from the nearest town, had been abandoned in the 1970s because of a lack of water. “I looked out the window and saw tire tracks, flagging and a bunch of two-by-two stakes,” Hoyt said. “My heart just sank.”

Department of the Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke has denied that the decision to reduce Grand Staircase and the neighboring Bears Ears National Monument had anything to do with ranching or mining. But during a visit in May, Zinke openly touted the region’s vast coal deposits. “Zinke toured the monument by helicopter,” Hoyt says. “He was carrying around a huge chunk of coal from the Kaiparowits Plateau in his truck. Don’t tell me this isn’t about mining.”����

“Our monuments are being bled dry. But if we could get funded again, things could change,” says Spalding.

Others see clear signs of political favoritism in the redrawn boundaries. In August, released its draft resource management plan for the Grand Staircase. One section outlined a plan to sell off roughly 1,600 acres of land within its boundaries. One of those parcels listed for “disposal” was in Johnson Canyon, a scenic area on the monument’s western border, adjacent to land owned by Utah state legislator Mike Noel. (Ryan Zinke later denied any plans to sell off land within the monument.)

“As I see it, this administration, with the help of the Utah delegation, is stealing these lands from the citizens of this country,” Blake Spalding, owner of a local restaurant called Hell’s Backbone Grill, told me. Spalding is a public-lands advocate and in the local effort to protect the Grand Staircase. “They are not at all interested in hearing from the pro-monument business owners who live in the gateway communities around the monument.”

Of course, proving that a definitive link exists between the Trump administration’s policies and recent damage to the local environment is almost impossible given the scarcity of data.��One report published by staff archaeologist Matt Zweifel, obtained by Grand Staircase Escalante Partners through a FOIA request, stated that between 2011 and 2015, there were 35 documented cases of damage or vandalism to paleontological sites across the monument.��According to��BLM��spokesperson Larry Crutchfield, based on “anecdotal” information from various park staff, there has been no appreciable increase in reports of vandalism in the last ten years.

But one citizen science initiative is painting a different picture. As of early October, 374��individual reports have been filed by visitors to the Grand Staircase, ranging from “using live old growth trees for firewood” to “cryptobiotic soil damaged by cattle.” Those reports were logged using an app called , which allows visitors to describe and pinpoint damage that they encounter using an interactive map. The most frequently reported infraction, by far, has been illegal off-road vehicle use, says Danielle Murray, policy director for the , the Durango-based non-profit that developed the app. According to Murray, the Upper Paria River Canyon corridor (where Peter Jensen encountered vehicle damage in May) has emerged as a major hotspot for illegal off-roading.

Spalding says that the uptick in damage can also be attributed to the monument’s severely diminished staff and budget, which this year is less than half of its $10.4 million 2003 allotment. “We only have one law enforcement ranger remaining,” she says. “Our monuments are being bled dry. But if we could get funded again, things could change.”

In spite of the cuts, visitation is “ass-kickingly” up, Spalding says, pointing out that the downsizing has itself served as a kind of unintended publicity for the monument. “Many of these people are wanting to come to see and experience the Grand Staircase before it’s ruined,” she says. “We’re going to fight like hell to make sure that doesn’t happen.”