For 40 years, Outside has sent writers on first descents of rivers, explored the latest fads in fitness and nutrition, watched Everest go from the proving ground of serious mountaineers to a playground for rich explorers, and tested more gear than we could possibly count. As part of our 40th anniversary, we've decided to roll out a series of lists exploring the best of our coverage. First up: the significant, beautiful, and terrifying destinations that loom large in our imaginations.

Slickrock Trail

If Moab, Utah, is mountain biking’s mecca, then Slickrock is the sport’s holiest altar. This trail epitomizes the area’s world-class riding: the 10.7-mile loop is almost entirely on smooth, red Navajo sandstone and offers stunning views of the desert. Tires latch onto the slickrock like Velcro, making all the steep climbs and descents totally rideable—if you have enough chutzpah. —Axie Navas

�Ѳ������������’s

When describing a wipeout he witnessed at the cold-water big-wave surf break, Grant Washburn, in an interview for the book , said “I was shocked at the ferocity, the gravity, the mercilessness…It seemed entirely possible that his head could be torn clean off.” Located about 25 miles south of San Francisco in the sleepy coastal town of Half Moon Bay, �Ѳ������������’s was pioneered by Jeff Clark, a local carpenter, who surfed there, alone, for 15 years. It wasn’t until 1994, when renowned Hawaiian big-wave surfer Mark Foo drowned while surfing there, that the wave really made its mark. Seventeen years later, Hawaiian Sion Milosky also drowned at the break. From November through March, organizers of the Titans of Mavericks surf contest (the name of the event and the waiting period has periodically changed slightly since its inception in 1999) wait for conditions worthy of holding the event: ideally at least a 20-foot swell coming from the northwest with light east winds. When it’s really on, the surf can range from triple-overhead to 80-foot faces. Oh yeah, and plenty of great white sharks are out there, too. —Matt Skenazy

McCandless Bus

Christopher McCandless died 24 years ago, but the patron saint of the anti-consumer ethos is as relevant as ever. Just look at the turquoise shell of Bus 142, which remains buried in the Alaskan wilderness, riddled with bullet holes. The bus remains a shrine for McCandless’ self-identified disciples, many of whom make annual pilgrimage to pay homage—and many of whom have either died or had to be rescued themselves. —Gregory Thomas

Heartbreak Hill

The final of the four notorious Newton Hills of the Boston Marathon, Heartbreak Hill arrives after mile 20 of the 26.2-mile course. While the hill is only a half-mile long, it comes —after several quad-searing downhills—leading many runners to hit the wall. At the 1936 event, caught leader Ellison M. “Tarzan” Brown on the hills and patted him on the back as he passed. But Brown wasn’t having it—he took off and eventually won the race. Watching Kelley’s disappointing moment, Boston Globe reporter Jerry Nason dubbed the spot Heartbreak Hill. In the 80 years since, countless other marathoners have learned firsthand that the nickname holds up. —�ѴDZ��������Ѿ��������

Corbet’s Couloir

Jackson Hole’s single rowdiest run is arguably the legendary Corbet’s Couloir, a steep, narrow chute with a mandatory 10-foot air at the entrance. It might be the most puckering inbounds trail in the country, and it’s certainly one of the most visible: the tram drops skiers off at the top every ten minutes. The couloir was named after Barry Corbet, a Jackson ski instructor and mountain guide who looked up at the inverted funnel one day in 1960 and predicted, “Someday, someone will ski that.” —Axie Navas

Camp 4

An 11-acre, 35-site campground on the north end of Yosemite Valley in California. An epicenter for the Valley’s climbing culture since the 1950s, the area was used as a base camp by climbing pioneers like Tom Frost, Steve Roper, Royal Robbins, and Yvon Chouinard (who used to make and sell equipment in the campground). “What makes this dusty little campground so historic and unique is its freewheeling, dynamic spirit and the people drawn to it over the decades,” said Linda McMillan, vice president of the American Alpine Club, when the campground was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2003. In the past, climbers would live in the camp, sometimes illegally, for months at a time. Today, the Park Service enforces a strict limit: 30 days during the off-season and 14 days during the summer months. Which is why, these days, you’ll still see climbing icons like Alex Honnold living primarily just outside the park boundary in their vans. —Matt Skenazy

Boardman River

Walk up to any fisherman on any river in North America in June and ask what fly he’s using, and there’s a decent chance he’ll say Adams. The mayfly imitation has been fooling fish for 95 years, ever since a fly-tier named Leonard Halladay handed it to a friend named Charles Adams, who in turn took it to the Boardman River, a sleepy-looking little stream in Michigan’s lower peninsula. Adams proceeded to catch the hell out of some fish. Thousands of anglers have been doing the same using the parachute variation. “It’s the Swiss Army knife of dry flies. It can match a spinner or an emerging dun. You can rip the hackle off it and it’s a good cripple. Or you can skate a big one to mimic a crane fly,” says , a longtime guide and author of. “You’d never think that the most utilized dry fly in angling would come from this tiny place.” —Jonah Ogles

Katahdin

The most sought-after summit in North America isn’t in Alaska, or the Sierras, or the Rockies. It’s tucked among the pines in northern Maine and rises a mere 5,267 feet to a pile of granite blocks and a wooden picket sign. The top of Katahdin is the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail, and more and more people each year set aside months to trek the 2,200 miles it takes to reach it. The mountain represents the conclusion of what thousands of thru-hikers regard as the penultimate soul-searching excursion of their lives. “People say that it’s the most majestic mountain in eastern North America,” says Ron Tipton, executive director and CEO of the . “There’s something special about finishing the trail that way.” —Gregory Thomas

Kroger’s Canteen

Once a year, during the annual Hardrock 100 ultramarathon, you’ll find Roch Horton and a bottle of tequila perched on a small, exposed, windy pass in southwestern Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. Horton is the captain of perhaps the most legendary aid station in the sport of ultrarunning, , which sits at 13,100 feet, about halfway through the undulating course. While the aid station, named after the late alpinist and six-time Hardrock finisher Chuck Kroger, has gained notoriety for offering (or, more accurately, forcing) a shot of tequila to racers, it holds an almost spiritual place in many Hardrocker’s hearts. In fact, it’s the only aid station in the sport that has a wait list for those who want to man it—only former Hardrock finishers are allowed to apply. Exactly how do they get gear, food, water, and all that tequila up to 13,100 feet? Backpack. “We have the best seat in the house,” says Horton, “and we paid dearly for these tickets.” —Wes Judd

Alpe d’Huez

There are a lot of important climbs in the Tour de France, but the most iconic, by far, is the Alpe d’Huez, in the central French Alps. It was first included in the 1952 race and has been a regular stage finish since 1976. Riders pedal 8.6 miles and climb more than 6,000 feet up 21 hairpin turns with an average gradient of 8.1 percent and a max of 13 percent. Hundreds of thousands of fans routinely line the route. Why? It’s not just the scenery or the suffering—it’s the spot where race leaders are often cemented or challenged. Many of the Tour’s most well-known riders—including Fausto Coppi, Marco Pantani, and Lance Armstrong—have crossed the Alpe d’Huez finish line first. —Jakob Schiller

Newfoundland

Why Newfoundland? Because America’s most popular dog, the Labrador retriever, is from the province’s coast. The Lab, developed in the early 1800s as a strong swimmer with a soft mouth and webbed feet, rode small dories and helped its French, British, and Portuguese fishermen-owners collect codfish that slipped off of the longlines as they were hauled in. The breed was very much a product of his environment—the small fishing villages along the southern coast of Newfoundland. Even today, a rare few of those white-chested Labradors can be found in stunningly beautiful and isolated fishing communities like Grand Bruit (officially depopulated), Burgeo, and La Poile. But their legacy may very well be asleep at your feet right now. —Grayson Schaffer

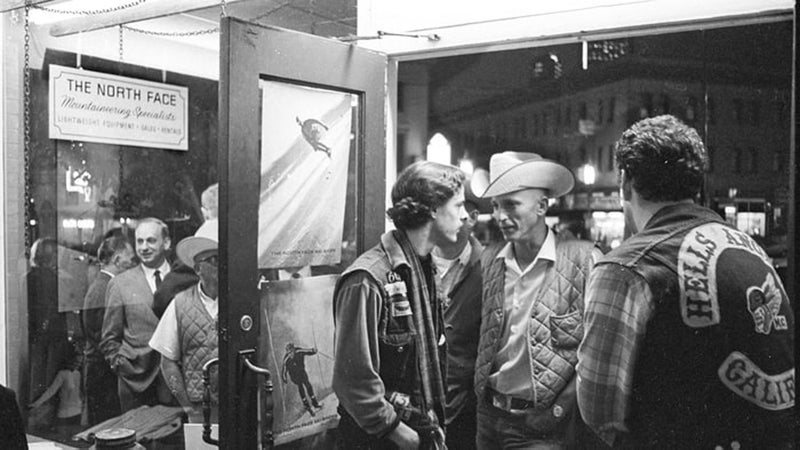

The North Face’s North Beach Store

On October 26, 1966, The North Face store opened on North Beach in San Francisco. The Grateful Dead played, a poster of the latest album from Bob Dylan (Blonde on Blonde) hung in a window, and Hells Angels guarded the door from unwanted party crashers. In the company’s first magazine, published the same year, 23-year-old co-founder Doug Tompkins wrote, “It is our express aim to help people equip themselves with the most practical gear to fit their needs and to reduce over-equipping…we have arbitrarily drawn the line for gimmicks and gadgetry. Hopefully, it will be noticed that we carry no such merchandise.” —Ben Fox

Chamonix, France

Chamonix is to big-mountain skiing what the North Shore of Oahu is to surfing—a proving ground and a place to cement your legacy. Glen Plake has been a regular forever, and Andreas Fransson called it home as well. Nowadays you can’t walk through the streets without running into an up-and-coming pro. The draw? Lots of big, scary, iconic lines under the shadow of Mont Blanc, plus unprecedented access. A cable car leaves right from town and hauls skiers up more than 9,000 feet to the 12,605-foot Aiguille du Midi peak, a jumping off point for many those world-famous descents. —Jakob Schiller

Everest Base Camp

Each spring, like Brigadoon, the teeming city known as Base Camp awakens at the foot of Mount Everest to support the ambitions of roughly 600 successful summits in a good year. In a bad year, and there have been a lot of them lately, Base Camp becomes the backdrop to a theater of horrors. In 2014, some 16 high-altitude workers died in an avalanche in the Khumbu Icefall, touching off a tense, days-long labor dispute in camp that ultimately ended with the season being canceled. In 2015, the Nepal earthquake triggered an avalanche that killed 19 people in Base Camp, including a camp doctor and Google executive Dan Fredinburg, who was hoping to bring a Street View camera up the mountain. Base Camp is often derided for its crowds and questionable sanitation, but it’s still one of the most beautiful places to trek, rest, or mourn on the planet. —Grayson Schaffer

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

Alaska is a state filled with impressive landscapes: Denali National Park, Kodiak Island, any number of glaciers. But none are so pristine as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). In the final days of the Obama presidency, there was hope among a certain circle of environmentalists that ANWR, a South Carolina–sized chunk of wilderness, might be named a national monument. Those hopes were misplaced. As a result, the oil companies that have been drooling over the reserves held under the vast expanse are more likely than ever to finally gain access. The loss would be immense. ANWR is the most biodiverse place within the Arctic Circle and is the calving ground for the Porcupine Caribou herd, a group of 160,000 mammals that migrate 1,500 miles to the Beaufort Sea each year. It is one of those few roadless, humanless places that exists as it did a hundred or even a thousand years ago. “It’s the wildest place in North America, and maybe even the world,” says Steve Barker, founder of Eagle Creek. “The threat of oil exploration is probably a 40- to 50-year window. If we can keep it protected beyond that, I think it’ll be OK.” —Jonah Ogles

Gila Wilderness

No doubt, the creation of the National Park Service in 1916 was monumental, but the creation of the first American wilderness area 30 years later was ultimately more forward-thinking. In urging the Forest Service to set aside 755,000 acres of southwestern New Mexico as the Gila Wilderness, Aldo Leopold saw how development’s many accompanying disturbances—noise, light, rampant crowds—could negatively affect the land and wildlife. “This was the first time that any nation, at that time, decided to check its headlong rush to develop its resources and to protect its wild places that are so important to the core of this country,” says Jamie Williams, president of the . As Congress proves itself unwilling to conserve threatened landscapes and Republicans move to sell what land they can, we’re more grateful than ever for those places that remain as far from human impact as possible. —Erin Berger

South Georgia Island

While Roald Amundsen claimed the most coveted prize of Antarctic exploration in 1911 when he reached the south pole, it was Ernest Shackleton’s epic four years later that cemented South Georgia Island as the fabled crucible of southern castaways. After Shackleton’s ship Endurance was crushed in the pack ice in 1915, he and his 27 men sailed to Elephant Island, where 22 men waited while Shackleton and six others went for help. They reached South Georgia’s southern coast after two weeks at sea in a lifeboat, but then they needed to cross the glaciated southern island on foot to reach the whaling settlements along its northern coast. Amazingly, Shackleton was able to find help and rescue his crew to a man. That journey, across the interior of South Georgia, home to millions of emperor penguins, has become popular as a bucket list item, and rightly so. Tour operators offer guided trips that retrace Shackleton’s crossing, but with better food. —Grayson Schaffer

The Confluence

In August 1869, John Wesley Powell stood in the Grand Canyon at a point where the Little Colorado River joined the Colorado River on its path to the Pacific Ocean and wrote these words: “We are three quarters of a mile in the depths of the earth, and the great river shrinks into insignificance as it dashes its angry waves against the walls and cliffs that rise to the world above; the waves are but puny ripples, and we but pigmies, running up and down the sands or lost among the boulders.” Thousands of individuals have since experienced the same feeling at perhaps the most beautiful point in one of the most awe-inspiring places on the planet. It is here that the colorful waters from the two rivers twist and dance until they have merged. It is here that the Hopi, Navajo, and Zuni believe their people emerged. And it is here that developers want to that would bring some 10,000 individuals from the rim to the confluence itself. “Should that come to pass, it would stand as an act of sacrilege in the eyes of everyone who has ever been touched by that place,” says Kevin Fedarko, author of . “It will inflict irreparable harm upon the integrity of a landscape that has no equal anywhere else on earth.” —Jonah Ogles

Le Mourillon, France

Jacques Cousteau became the ocean savior we know on a Sunday in 1936. At 26, he might have continued a career in the French military, photographing the sea only as a hobby. Instead, a near-fatal car accident sent him to Le Mourillon, a seaside town in the south of France, to swim his way to recovery. One morning, Cousteau donned Fernez goggles and saw what lived in the clear Mediterranean waters. As he wrote in his 1953 autobiography, , “Sometimes we are lucky enough to know that our lives have been changed…It happened to me that summer’s day.” His underwater documentaries over the following 60 years captured the public’s attention and raised the urgency of marine conservation—including for Cousteau himself, who would develop into an activist over his career. —Erin Berger

Kawarau Bridge

When Kiwis A.J. Hackett and Henry van Asch began developing bungee-jumping cords with the help of Auckland University Scientists, they were sure people would pay to experience the thrill. The New Zealand Department of Conservation wasn’t as easily convinced but granted them a 30-day license to operate from the Kawarau Bridge in Queenstown. On November 12, 1988, 28 people paid $75 each to launch themselves off of the 43-meter bridge with a bungee cord attached to their ankles. With that, the first commercial bungee-jumping company was founded. The launch of the Kawarau Bridge Bungy site has been hailed as the birth of adventure tourism in New Zealand. And while BASE jumpers and wingsuiters have long surpassed the adrenaline factor, bungee-jumping was one of the first examples of extreme sports on the planet. —Ben Fox

Festina Car

Just before the start of the 1998 Tour de France in Ireland, customs police stopped Willy Voet, a soigneur for the Festina cycling team, near the France-Belgium border. When French police searched the vehicle, they found 234 doses of EPO. Voet was arrested, and in the coming years, all nine members of the 1998 team would admit to using EPO, beginning a string of drug scandals and reforms: the formation of the World Anti-Doping Agency, the creation of an EPO urine test, and the eventual disqualification of 12 of 19 recent Tour winners. Sure, the scandal occurred after Dr. Michele Ferrari’s famous 1994 quote—“EPO is not dangerous. It’s the abuse that is. It’s also dangerous to drink ten liters of orange juice.”—but this was the moment when the sporting world was first confronted with the existence of sophisticated team-sponsored doping programs. Even after the 2006 Operacion Puerto case and Lance Armstrong’s 2013 admission, suspicion lingers on the Tour, in the Olympics, and across cycling. The Festina car was just the first time anyone had cast light on the problem. —Jonah Ogles

Yvon Chouinard’s Tin Shed

In 1966, Yvon Chouinard moved his burgeoning piton-making business into a tin shed in Ventura, California. He called it Chouinard Equipment. The company made axes, hammers, hexes, and nuts and spawned both Patagonia and Black Diamond (which purchased Chouinard Equipment in 1989). Today, the shed remains on Patagonia’s campus, and Chouinard himself can still be found there, fiddling with things like aluminum bars that he tacked onto fishing boots to increase traction on slippery riverbeds. The shed is so iconic that Patagonia named its venture capital arm after it: now funds anyone looking to tackle a problem with hard work and ingenuity. —Jonah Ogles

Source of the Amazon

Dozens of expeditions (like Gonzalo Pizarro and Francisco de Orrelano in 1541) have tried to pinpoint the Amazon’s source, and even more (like ) have tried to chart its tributaries. Despite their efforts, the . Most of the water in the Amazon comes from the Río Marañón drainage, its headwaters on the slopes of Cerro Yerupajá, the second-highest mountain in Peru. Yet another study says it’s the Apurimac drainage. “Both seemed to have merits,” says explorer Rocky Contos. “The Mississippi River is thought to have its source in Minnesota, but the most distant point is in Wyoming, up the Missouri River.” Contos discovered that the most distant source is on the Cordiller Rumi Cruz, where snowfields trickle into the Rio Mantaro, and set out to float the entire length in 2012. But even still, some remain unconvinced that it is the true source. —Charlie Ebbers

Camp Hale

We would have poorer-quality winter gear, less advanced avalanche control, and a lot fewer ski resorts were it not for the U.S. Army’s 10th Mountain Division, the ski-mounted unit that fought in the mountains of Italy during World War II. The group , where the white-camouflaged troops practiced basic military maneuvers and ski techniques on nearby Ski Cooper while testing specialized gear—waterproof-breathable outerwear, lightweight winter tents, and high-performance base layers—made for the division. After the fighting in Europe ended, many of the vets returned to start their own ski hills, including Vail and Aspen, backed by their extensive new knowledge of how to travel safely in the mountains. “The 10th Mountain brought experience and ingenuity with them when they returned to the U.S. after the war,” says Susie Tjossem, executive director of the Colorado Ski and Snowboard Museum and Hall of Fame. “Their can-do attitude and no-nonsense work ethic helped community ski areas evolve into mainstream recreation for the masses.” —Axie Navas

Window of Apollo 17

On December 7, 1972, three days before the Apollo 17 spacecraft landed on the moon, an astronaut on board looked out the window, grabbed his 70-millimeter Hasselblad camera, and took the . When the series of four quick snapshots was developed, the second and clearest shot would become the poster image of Earth as a finite, fragile sphere in the universe—not to mention one of the most influential photos in the environmental movement. What we may never know about the Blue Marble is who took it—Eugene Cernan, Ronald Evans, or Harrison Schmitt? All three of the primary astronauts aboard Apollo 17 have claimed responsibility, though only Schmitt is still alive. “We had anticipated that we would be seeing that full view of Earth, but I’ll tell you, when you actually have the opportunity to see it firsthand, it really does get your attention,” he says. “It’s great that everybody effectively on earth has now had a chance to see that same picture we had, but it’s much better to see if with your eye than through a camera.” —Erin Berger

Brooklyn Boulders

Some of America’s best creations have started in garages. Apple and Amazon grew out of their original, crusty, motor-oil-stained confines and into sleek corporate headquarters, but the original , the climbing gym cum creative space born in 2009 in the old Daily News garage in Gowanus, is still there. Its 22,000 square feet of top-roping, lead climbing, and bouldering walls have attracted amateurs and pros like Ashima Shiraishi and stands as New York City’s hive for the vertically inclined. Sure, BKB has grown (it now has locations in Queens, Chicago, and Massachusetts), but its graffitied climber heart remains in Brooklyn—resident artists program, co-working space, and all. —Will Egensteiner

Rift Valley Province

Kenya’s Rift Valley is the epicenter of distance running. The small towns of Iten, Kaptagat, and Nyahururu are brimming with the world’s best: Olympic champions, world champions, and world record holders all live and train there. “All of Kenya’s runners come from the Rift Valley,” says Adharanand Finn, author of . “And between them, they have completely dominated the world of marathon and half marathon running. Considering that marathon running is pretty much the world’s most universal and accessible sport, for it to be so completely dominated by people from one small corner of the world is quite incredible.”—Molly Mirhashem

Great Barrier Reef

The massive feature—stretching1,400 miles along Australia’s northeast shore—is home to more than 2,000 species of coral, fish, and marine mammals. It’s also dying. Massive portions of the reef have bleached as a result of warming waters, and it appears that nothing can stop it. Today, it has become one of the greatest barometers for human impact on the planet and one of a growing number of places where you can literally watch the climate change in front of you. —Jonah Ogles

Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station

In 1912, Norwegian grizzly-man Roald Amundsen and Royal Navy officer Robert Scott raced each other across the earth’s icy bottom to become the first human beings to reach the South Pole. (Amundsen beat Scott by a mere five weeks.) Forty-two years later, the United States erected the first enduring man-made structure: a research station named in the explorers’ honor. “It’s one of the major engineering and logistical achievements of the last 100 years,” says polar explorer Eric Larsen. Apart from housing scientists year-round, the has been rebuilt and expanded several times over the years and now includes a visitor center for the growing cadre of polar enthusiasts who sled, bike, ski, and wind-propel themselves across the barren icy plain each year. —Gregory Thomas

Challenger Deep

In 2012, film director James Cameron became one of three humans ever to set eyes on the Mariana Trench’s Challenger Deep—the deepest point on the planet. His solo expedition was only the second time a person had been there. The first was the 1960 mission of retired U.S. Navy captain Don Walsh and late Swiss engineer Jacques Piccard, who were the first to descend 35,756 feet into the Pacific Ocean and witness the pitch-black terrain. It is a place so dark and remote that direct observation is the only way to truly comprehend what it is like. “There will always be a role for manned submersibles,” says Walsh. “There is a certain mystique to having ‘one of us’ down there,” —Eric Killelea

Methuselah Tree

Since its discovery in the 1950s, the 4,800-year-old in Northern California’s White Mountains has attracted scores of sojourners seeking enlightenment from an object that has been around half as long as human civilization. Most have returned befuddled. That’s because the ancient bristlecone pine, named after the oldest man in the Bible, resides all but camouflaged in a grove of other elderly trees—charred, gnarled, and generally ravaged by time, its existence visible in only a sliver of living wood on its twisted trunk. Rangers are mum when asked to pinpoint the true Methuselah for visitors, which preserves the mystique. After all, it’s not the destination, it’s the journey. —Gregory Thomas

Edward Abbey’s Trailer

From 1956 to 1957, Ed Abbey, the original #VanLife influencer, scored a job as a ranger in what was then, as he referred to it, “Arches Natural Moneymint.” As part of that arrangement, Abbey was given a trailer just across the road from Balanced Rock. It was that paved scenic loop, the ultimate convenience of modern drive-by tourism, that Abbey so passionately railed against in his “Polemic: Industrial Tourism and the National Parks,” which appeared in his 1968 book, . Today, the former home of the trailer is marked by a little fenced outcrop, a piece of sewage pipe, and an amazing south-facing view of a landscape that, since January 2016, includes Bears Ears National Monument, a testament to Abbey’s legacy as a preservation hawk. —Grayson Schaffer

Bottleneck on K2

When people refer to K2, the world’s second-highest peak, as the mountaineer’s mountain or the world’s most dangerous peak, much of that lore comes down to one critical segment of the route: the bottleneck. The narrow 60-degree choke point of rock and ice at 27,200 feet forces climbers to inch their way up single file in the shadow of a great, unstable ice wall. “Any route on K2 is dangerous because the mountain is so consistently steep that stuff just comes down,” says mountaineer and guide Adrian Ballinger. “Rocks, snow avalanches, ice fall from the serac, and unfortunately sometimes climbers.” It was a section of the bottleneck that collapsed on August 1, 2008, sending debris down into the crowded bottleneck and touching off a catastrophe that would ultimately kill 11. Since then, climbers have returned to the mountain and even ushered in K2’s guided era in 2015, but success is as elusive as ever, and likely forever will be. —Grayson Schaffer

Pipeline

The most famous, dangerous, crowded, and photographed wave on the planet. In 1961, Phil Edwards was the first to surf the hollow left on the North Shore of Oahu. (The name Pipeline specifically refers to the left but often includes the corresponding right, technically called Backdoor.) Since 2000, at least six people have died at the break while countless more have left the water with concussions, broken bones, and lacerations from the shallow and sharp reef. In early 2017, Hawaiian surfer Kalani Chapman was pulled unconscious from churning shore pound before lifeguards eventually resuscitated him. Each December, the final contest in the World Surf League is held at Pipeline, often deciding the year’s champion. —�Ѳ��ٳ��������Բ�����

Canyons

Ask any ultramarathoner who has run Western States about the Canyons, and they’ll likely shudder with dread. This roughly 13-mile stretch of the annual race takes runners down thousands of feet into the arid, dusty canyons of Central California in early summer heat. Located roughly halfway through the course, racers usually hit the Canyons during the hottest part of the day. “I’ve found myself in my most desperate yet critical miles of the race in the Canyons during each of my three Western States runs,” two-time race winner Rob Krar told �����ԹϺ��� in 2016. “Heat is the devil and what makes Western States so difficult. Nothing can prepare one for that furnace.” —Wes Judd

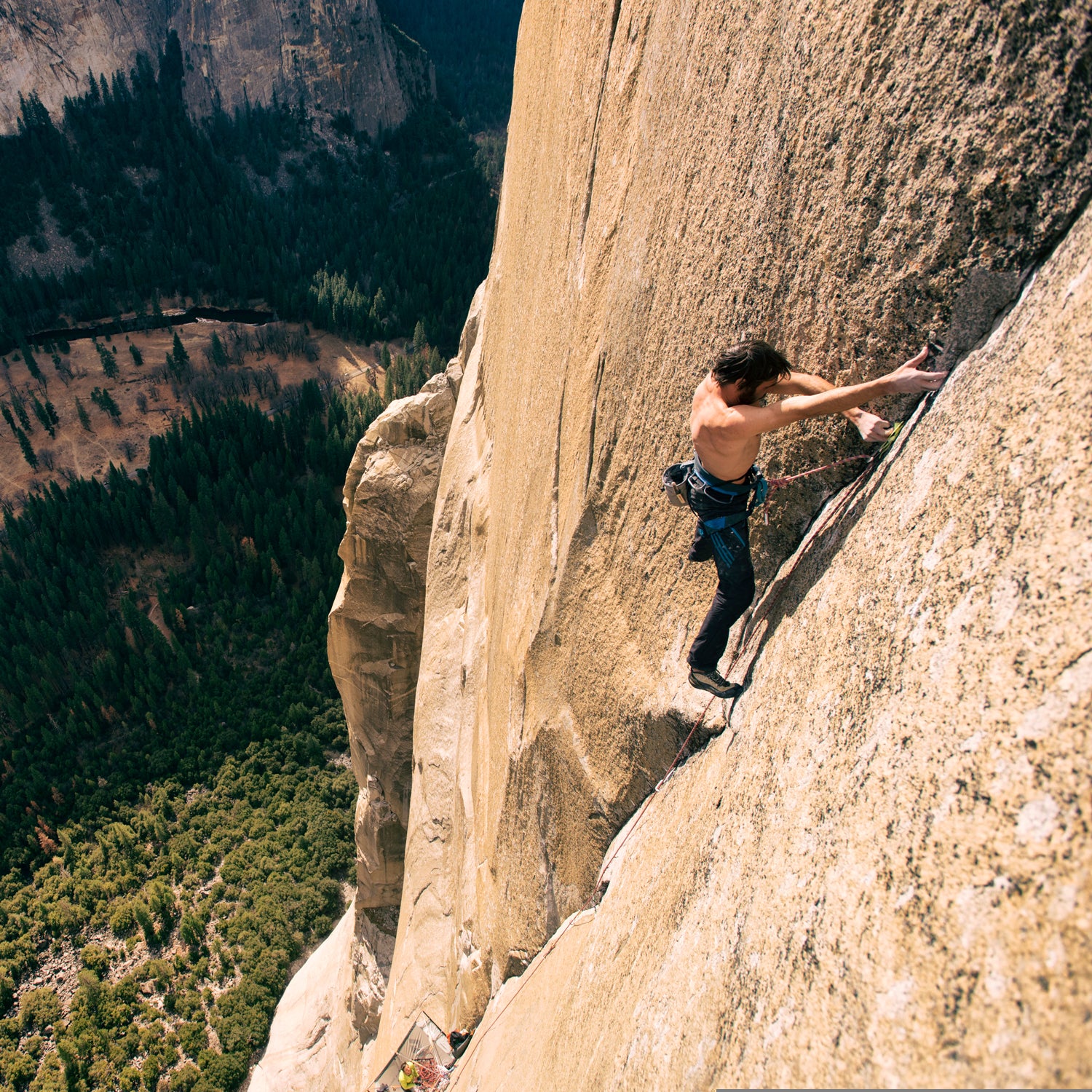

The Dawn Wall

The Southeast face of El Capitan in Yosemite Valley is home to the most difficult big-wall climb in the world. First climbed in 1970 by Warren Harding and Dean Caldwell during an epic 28-day push that included using bolts, fixed lines, and other forms of aid climbing to ascend the route. When the pair finally reached the summit, after 2,500 feet of climbing, one of the gathered reporters asked Harding why they climbed the route. “Because we’re insane,” Harding famously replied. “Can’t be another reason.” Nearly a half-century later, over 19 days in January 2015, Tommy Caldwell (no relation to Dean) and Kevin Jorgeson made the first free ascent, using only natural features to ascend the route, after seven years of work. The climb was covered by the New York Times, NPR, and dozens of other national news organizations. No other climb, save Everest, has garnered mainstream attention like the Dawn Wall. In 2016, Czech climber Adam Ondra made the second free ascent during his first trip to Yosemite Valley. It took him just eight days. “It would be interesting to do the Dawn Wall much faster,” Ondra said after. “Maybe I will come back and try again some day.” —�Ѳ��ٳ��������Բ�����

Jacob’s Ladder Rapid

Among whitewater kayakers of the West, , on the North Fork of the Payette River, stands as a kind of benchmark for Class V boaters. It’s one of those lines that gives people night sweats. Run it consistently and you can call yourself a Class V kayaker; mess it up and you’re in for a long, painful, even deadly swim. The rapid starts with a folding diagonal wave, and then dumps over the Rock Drop. To run it correctly, you need to be moving across the current from right to left and into the calm pool behind the Rock Drop. If you miss that critical move, you’re likely going over the extremely shallow Taffy Puller drop upside-down. If you swim there, it’s right into Ocean Wave, and the Golf Course, which has at least 18 holes. Yeesh. —Grayson Schaffer

KT22

The world’s great chairlifts are more than mechanical conveyances that get you to the top of the hill: they’re part of skiing’s soul. Mad River Glen’s single chair. The first lift ever at Sun Valley in Idaho. Another one of our favorites: . Originally built in 1958 (Squaw upgraded the old double to a high-speed express in 2005), it was the chair of late freeskiing legend Shane McConkey, in part because of the unbelievable terrain it accesses: the quad dumps riders on top of 2,000 vertical feet of steep chutes and glades. “You want to show everyone how rad you are on a powder day, you gotta ski that in front of everybody, cause they’ll all be watching,” McConkey said in a . —Axie Navas

Mount Tamalpais

One day in the mid-1970s, Joe Breeze was looking down on San Francisco from the top of , taking a break from riding his bike down the singletrack trails, when he said to his buddy, “This is fun, but who else is going to want to do this?” At the time, mountain biking, as we now call it, was the habit of only a few dozen people who outfitted old Schwinn bikes with balloon tires. “It was sort of a natural thing,” says Breeze, who built the first purpose-built mountain bike and now runs the . “We’re riding on the road. Why not ride on the trails and double what we can ride?” Before long, friend after friend was borrowing Breeze’s bike and returning it after a run down Mount Tam with a big smile on their face. “Mountain bikes went from Mount Tam to the rest of the world,” says Breeze. —Jonah Ogles

Mount Washington Weather Station

Perched high atop , in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, is an observatory that measures the world’s worst weather. Founded in 1932 with a $400 grant from Dartmouth College, it is a place of extremes. In 1934, observers recorded the highest wind speed (231 mph) on earth. In winter, temperatures on the top of Mount Washington regularly drop to minus 40 degrees. Three weather observers live in the stone observatory, working 12-hour shifts, 365 days a year. “It’s an isolated job,” says Mount Washington Observatory president Shannon Schilling, “but because we use human observers, we have one of the longest spans of accurate weather data in the world.” —Ben Fox